Mariette Hartley Topless

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Пожалуйста, введите три или более символа

Используя ЛитРес, вы соглашаетесь с условиями обслуживания

Присоединяясь к ЛитРес, вы заботитесь об экологии

Укажите электронную почту и вы всегда будете в курсе новинок

минимальное количество символов 120 (0 / 120)

Ваш отзыв добавлен и будет виден другим пользователям после проверки модератором, а сейчас Вы можете поделиться им с друзьями

Получите 100 бонусных рублей

на ваш счет в ЛитРес.

Напишите содержательный отзыв

длиной от 120 знаков

Мы используем куки-файлы, чтобы вы могли быстрее и удобнее пользоваться сайтом. Подробнее

Купите 3 книги одновременно и выберите четвёртую в подарок!

Чтобы воспользоваться акцией, добавьте нужные книги в корзину. Сделать это можно на странице каждой книги, либо в общем списке:

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize its key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (February 2021)

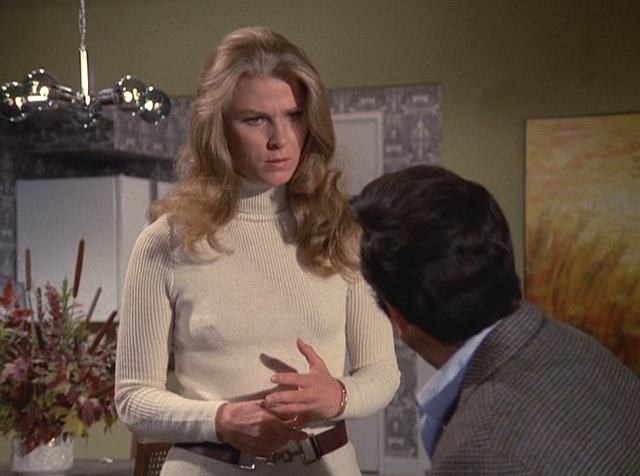

Mary Loretta "Mariette" Hartley (born June 21, 1940) is an American actress.

Hartley was born in New York City, the daughter of Mary "Polly" Ickes (née Watson), a manager and saleswoman, and Paul Hembree Hartley, an account executive.[1] Her maternal grandfather was John B. Watson, an American psychologist who established the psychological school of behaviorism. Hartley has a younger brother, Paul, who is a writer (The Seventh Tool) and research philosopher. She grew up in Weston, Connecticut, an affluent Fairfield County suburb within commuting distance to Manhattan.

She graduated from the Carnegie Institute of Technology, now known as Carnegie Mellon University, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1965.[2]

Hartley began her career as a 13-year-old in the White Barn Theatre in Norwalk, Connecticut. In her teens as a stage actress, she was coached and mentored by Eva Le Gallienne. She graduated in 1957 from Staples High School in Westport, Connecticut, where she was an active member of the school's theater group, Staples Players. Hartley also worked at the American Shakespeare Festival.[3]

Her film career began with an uncredited cameo appearance in From Hell to Texas (1958), a Western with Dennis Hopper. In the early 1960s, she moved to Los Angeles and joined the UCLA Theater Group.[4]

Hartley's first credited film appearance was alongside Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea in the 1962 Sam Peckinpah Western Ride the High Country; the role earned her a BAFTA award nomination. She continued to appear in film during the 1960s, including the lead role in the adventure Drums of Africa (1963), and prominent supporting roles in Alfred Hitchcock's psychological thriller Marnie (1964) — alongside Tippi Hedren and Sean Connery — and the John Sturges drama Marooned (1969).

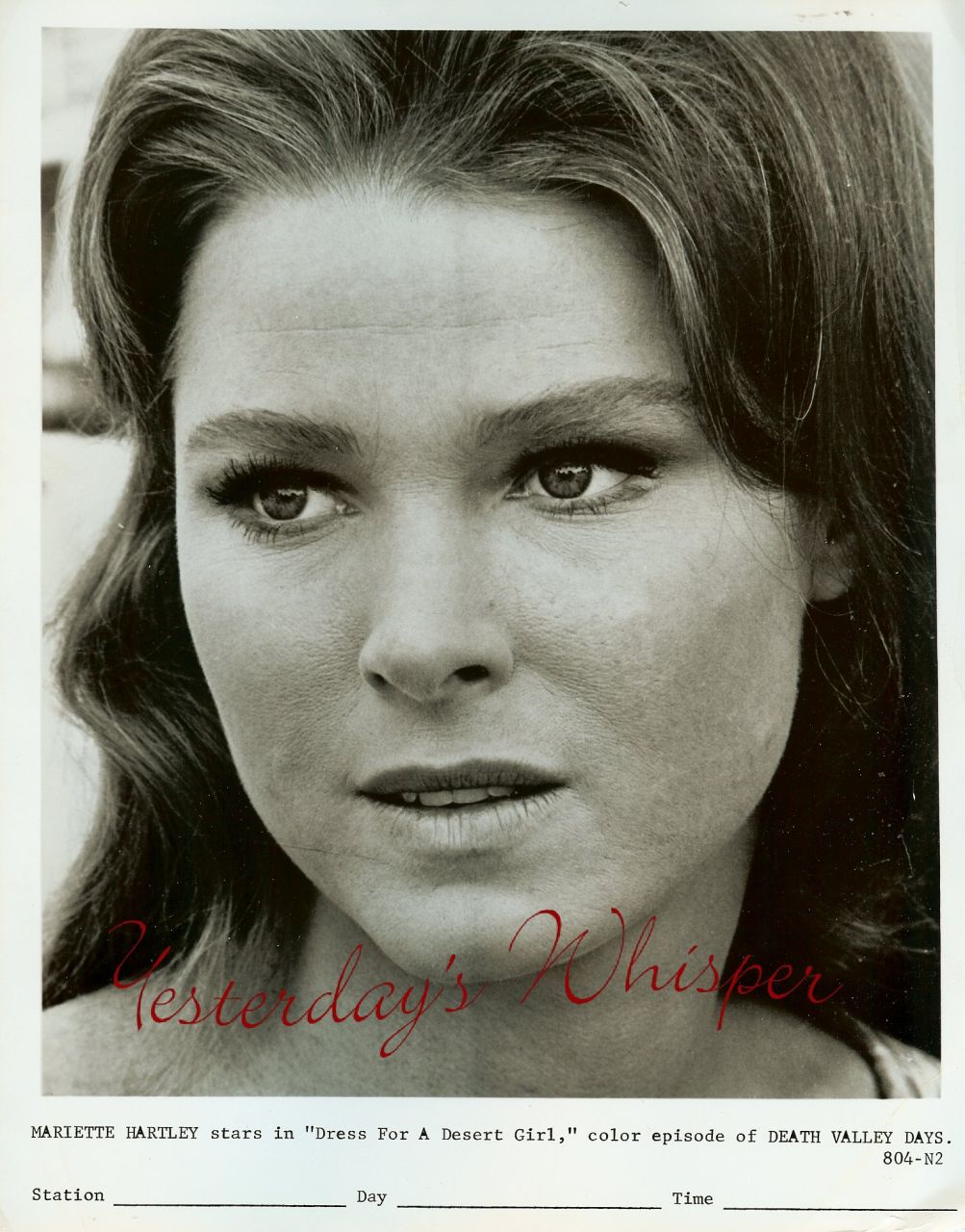

Hartley also guest-starred in numerous TV series during the decade, with appearances in Gunsmoke, The Twilight Zone (the episode "The Long Morrow"), The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters (starring a young Kurt Russell), the syndicated Death Valley Days (then hosted by Ronald Reagan),[5] Judd, for the Defense, Bonanza and Star Trek[6] among others. In 1965, she had a significant role as Dr. Claire Morton in 32 episodes of Peyton Place.

Hartley continued to perform in film and TV during the 1970s, including two Westerns alongside Lee Van Cleef, Barquero (1970) and The Magnificent Seven Ride (1972), and TV series including Emergency!, McCloud, Little House on the Prairie, Police Woman, and Columbo — starring in two editions of the latter alongside Peter Falk; Publish or Perish co-starring Jack Cassidy (1974) and Try and Catch Me with Ruth Gordon (1977). Hartley portrays similar characters as a publisher's assistant in both episodes.

In 1977, Hartley appeared in the TV movie The Last Hurrah, a political drama based on the Edwin O'Connor novel of the same name; and earned her first Emmy Award nomination.

Her role as psychologist Dr. Carolyn Fields in "Married", a 1978 episode of the TV series The Incredible Hulk — in which she marries Bill Bixby's character, the alter ego of the Hulk, won Hartley the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series. She was nominated for the same award for her performance in an episode of The Rockford Files the following year.

In 1983, Hartley reunited with Bixby in the sitcom Goodnight, Beantown, which ran for two seasons and brought her another Emmy Award nomination. (She worked with Bixby again in the 1992 TV movie A Diagnosis of Murder, the first of three TV movies that launched the series Diagnosis: Murder).

In the 1990s, Hartley toured with Elliott Gould and Doug Wert in the revival of the mystery play Deathtrap. Numerous roles in TV movies and guest appearances in TV series during the 1990s and 2000s followed, including Murder, She Wrote (1992), Courthouse (1995), Nash Bridges (2000), and NCIS (2005). She had recurring roles as Sister Mary Daniel in the soap opera One Life to Live (1999–2001; 10 episodes), and as Lorna Scarry in six episodes of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (2003–2011).

From 1995 to 2015, she hosted the long-running television documentary series Wild About Animals, an educational program.

In 2006, Hartley starred in her own one-woman show, If You Get to Bethlehem, You've Gone Too Far, which ran in Los Angeles. She returned to the stage in 2014 as Eleanor of Aquitaine with Ian Buchanan's Henry in the Colony Theater Company production of James Goldman's The Lion in Winter.

In January 2018, Hartley began a recurring role on the Fox first-responder drama 9-1-1 as Patricia Clark, the Alzheimer's-afflicted mother of dispatcher Abby Clark (Connie Britton).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hartley appeared with James Garner in a popular series of television commercials advertising Polaroid cameras. The two actors had such amazing on-screen chemistry that many viewers erroneously believed that they were married in real life. Hartley's 1990 biography, Breaking the Silence, indicates that she began to wear a T-shirt printed with the phrase "I am not Mrs. James Garner."[7] (Hartley went as far to have a shirt made for her infant son, reading "I am not James Garner's Child" and even one for her then-husband: "I am not James Garner!" James Garner's actual wife then jokingly had a T-shirt printed with "I am Mrs. James Garner.") Hartley guest-starred in an episode of Garner's television series The Rockford Files in 1979. The script required the two to kiss at one point and unbeknownst to them, a paparazzo was photographing the scene from a distance. The photos were run in a tabloid trying to provoke a scandal.[citation needed] An article that ran in TV Guide was titled: "That woman is not James Garner's wife!"[citation needed]

Between 2001 and 2006, Hartley endorsed the See Clearly Method, a commercial eye exercise program, whose sales were halted by an Iowa court after a finding of fraudulent business practices and advertising.[8][9]

She received an honorary degree from Rider College in 1993.

Hartley has been married three times. Her first marriage was to John Seventa (1960–1962). She married Patrick Boyriven on August 13, 1978, with whom she had two children, Sean (born 1975) and Justine (born 1978).[10] The couple divorced in 1996. In 2005, Hartley married Jerry Sroka.[11]

In her 1990 autobiography Breaking the Silence, written with Anne Commire, Hartley talked about her struggles with psychological problems, pointing directly to her grandfather's (Dr. Watson) practical application of his theories as the source of the dysfunction in his family. She has also spoken in public about her experience with bipolar disorder and was a founder of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.[12] She currently serves as the foundation's national spokesperson.[4]

In 2003, Hartley was hired by pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline to increase awareness of bipolar medications and treatments. She frequently promotes awareness of bipolar disorder and suicide prevention.[13]

In 2009, Hartley spoke at a suicide and violence prevention forum about her father's suicide.[14]

Episode: "For I Will Plait thy Hair with Gold"

Episode: "The Last Testament of Buddy Crown"

Episode: "Love and the Fighting Couple"

Episode: "To Carry the Sun in a Golden Cup"

Episode: "The White Plague Project"

Episode: "Have You Met Miss Dietz?"

Episode: "Snatches of a Crazy Song"

M.A.D.D.: Mothers Against Drunk Drivers

Episode: "Joshua and the Battle of Jericho"

Episode: "Caroline and the Twenty-Eight-Pound Walleye"

Episode: "O'er the Rampants We Watched"

House on the Hill (aka He's Out to Get You)

^ "Mariette Hartley Biography (1940–)". Film Reference Library. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

^ "Carnegie Mellon Alumni" (PDF). www.alumni.cmu.edu. Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

^ Delong, Thomas (2009). Stars in Our Eyes. Westport Historical Society. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-9648759-4-4.

^

Jump up to:

a b "Mariette Hartley". www.mariettehartley.com. Mariette Hartley. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

^ ""The Red Shawl" on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Data Base. December 30, 1965. Retrieved May 16, 2015. In 1968, Hartley appeared in Death Valley Days "Dress for a Desert Girl".

^ "Mariette Hartley Cherishes 'All Our Yesterdays'". StarTrek.com. November 2, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

^ Hartley, Mariette, and Anne Commire. Breaking the Silence. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1990, p. 185.

^ Shin, Annys; Mui, Ylan Q. & Trejos, Nancy (November 6, 2006). "Seeing the See Clearly Method for What It Is". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

^ Richards, David (August 2008). "See Clearly Method Investigation". Independent Investigations Group. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

^ Klein, Alvin (February 6, 1994). "A Bittersweet Homecoming for Mariette Hartley". The New York Times.

^ "It Didn't Happen in 60 Seconds, but Her Ads with Jim Garner Developed Mariette Hartley's Career". People. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

^ "Leadership". 2013 Annual Report. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. pp. 40–41. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

^ Morgan, John; Shoop, Stephen A. (August 1, 2003). "Mariette Hartley triumphs over bipolar disorder". USAToday.com. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

^ "Suicide and Violence Prevention: Creating a Safer Community". santabarbaratherapy.org. Santa Barbara Therapy. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2016..

50+ Mariette Hartley ideas | mariette hartley , hartley, actresses

Mariette Hartley - Новинки книг 2020 – скачать или читать онлайн

Mariette Hartley - Wikipedia

В сеть попали украденные снимки голых знаменитостей » uCrazy.ru...

Talking About Suicide With Mariette Hartley - YouTube

Mature Picture Post

Françoise Yip Nude

New Mature Pussy

Mariette Hartley Topless