Lula's disinformation 'office'

By @tupireport

For four years, Lula and leftist parties accused Jair Bolsonaro of maintaining a “hate office”, to supposedly spread false news and unfounded accusations against his opponents. Bolsonaro and allies were included in the still unfinished “ fake news inquiry ”, set up at the Federal Supreme Court (STF) by Minister Alexandre de Moraes.

Now, however, members of Lula government have their own “hate office”. An article by O Estado de S. Paulo published on the newspaper's website shows that the team that takes care of President Lula's personal pages keeps a network mobilized with hundreds of WhatsApp groups to "spread content" and "government agendas ” and attack Bolsonaro and right-wing allies.

Created in the electoral campaign, these WhatsApp/Telegram groups are managed by the “office” that takes care of the website “lula.com.br”, announced by the Worker's Party (PT) as Lula's official page on the internet, before he was elected, according to the report.

"LOVE OFFICE" FROM WORKER'S PARTY (PT)

On the website, PT members report that the movement on the networks brings together more than 25,000 volunteers who call themselves “ fake news hunters”. The site indicates the links to be part of one of the groups.

In this message, released on March 29, leftist groups claim that Bolsonaro committed a series of crimes and call for “jail” for the former president.

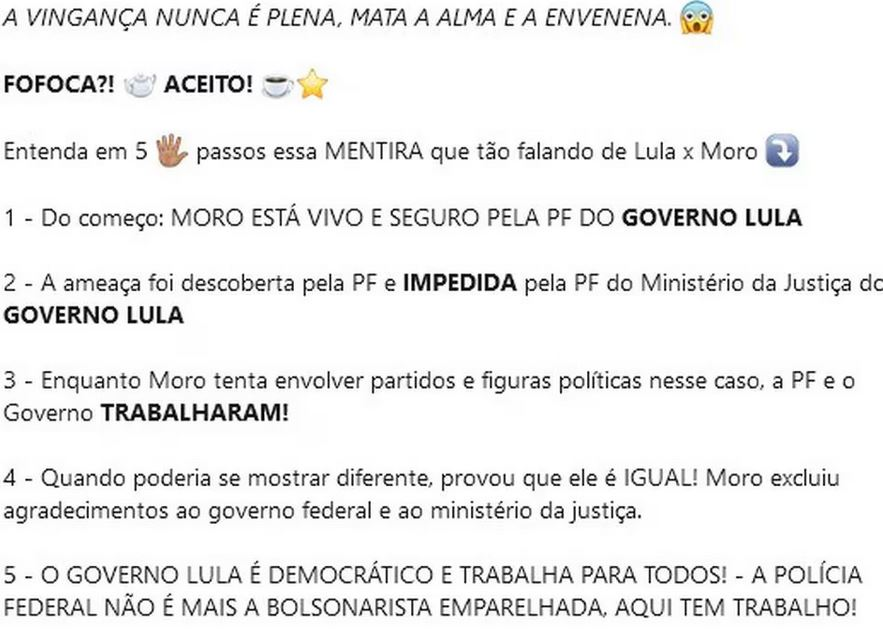

In pro-Lula groups, dozens of messages are also published to “clarify” and deny negative information about the president. One of the examples cited by Estadão is Lula's statement that the PCC's plan to kill Senator Sergio Moro (União-PR) would be "another frame" by the former Lava Jato judge.]

The leftist groups then created the “five steps” to clarify the “lie they are talking about Lula vs Moro”.

To Estadão , the Secretary of Communication of the Presidency of the Republic informed that it does not take care of the website www.lula.com.br and, therefore, “does not interfere in the administration of the channel, as well as the content produced and published”. The body said it manages only the president's official Twitter. The PT has not yet manifested itself.

JUSTICE AND MISINFORMATION

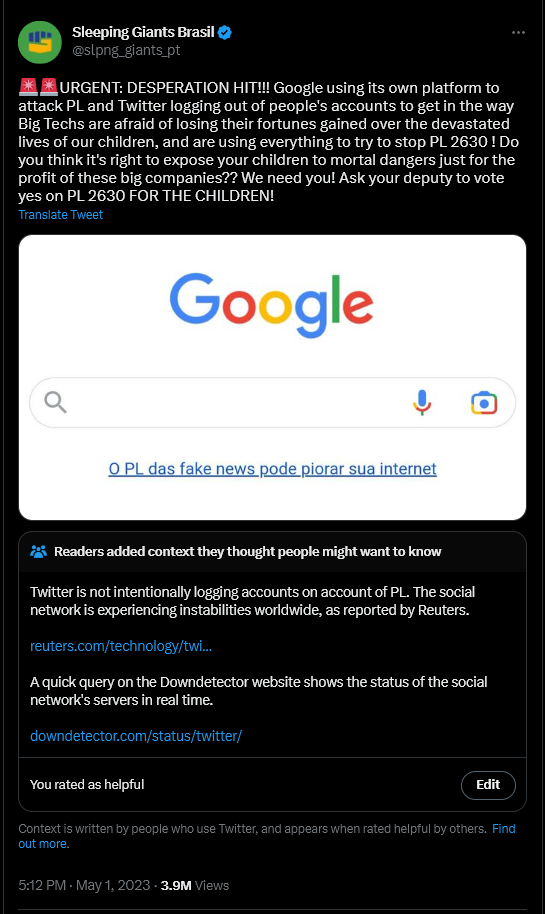

Recently, Justice Minister Flávio Dino published and declared on his networks that companies such as Google and Twitter were making and promoting advertisements against the Censorship Bill (PL / 2630), and asked that companies keep quiet about the issue.

However, Flavio Dino used a tweet from The Sleeping Giants profile, which was used by face news to accuse the companies.

With this, members of the Government Act directly by forging evidence to continue advancing against the precepts of freedom of expression and fair political play.

CENSORSHIP BILL (PL/2630)

The Brazilian lower house seems poised to fast-track the so-called “Fake News Bill,” after letting the proposal stall for almost three years — raising alarm bells for its potential to establish a hazardous precedent.

As the bill seeks to create a new framework for internet regulation in Brazil, critics argue that it endangers freedom of expression, privacy, and intellectual property rights, going even further than the European Union’s Digital Services Act.

In grappling with issues such as fake news, misinformation, and harmful content, the world is watching Brazil’s “Fake News Bill” with trepidation. One particularly troubling aspect regards the protection of politicians on social media platforms.

The bill’s provision to grant politicians sweeping immunity on social media may pave the way for an erosion of accountability and transparency in the digital sphere. This could lead to a decline in public trust in political institutions and a surge in the spread of false information.

Per Brazilian law, elected officials are protected from any sort of criminal or civil liability for their votes, opinions, and speeches.

This was a sacrosanct principle enshrined in the 1988 Constitution as a way to bury the 21 years of military dictatorship during which politicians were persecuted — and, on many occasions, jailed and killed — for voicing anti-government views. Congressman Orlando Silva, the bill’s rapporteur, wants to extend that protection to the online world.

But think tank ITS-Rio, which studies the effects of technology on society, believes the provision essentially grants politicians a “free pass to spread fake news and disinformation on the web, in the name of parliamentary immunity.”

Recent analysis by Jota, a legal news website, highlights the impact of parliamentary immunity, revealing that in the ten inquiries opened in the Supreme Court investigating fake news, digital militias, anti-democratic acts, and the January 8 riots, over 48 individuals are mentioned, including public officials and politicians — and could potentially evade investigation due to their status as “public interest persons.”

This assessment refers only to the five cases that are not under seal.

The bill prohibits platforms from suspending or limiting politicians’ accounts, even if they violate platform rules or spread disinformation. Supporters of this approach argue that it prevents politically motivated censorship or bias and that suspending or limiting politicians’ accounts could lead to the silencing of specific viewpoints or ideas.

However, this unequal content moderation empowers politicians to disseminate misinformation and hate speech without repercussions, ultimately undermining the fight against fake news and disinformation.

By providing politicians with such immunity on social media, the bill may inadvertently encourage the very behavior it claims to counter.

Given the prominent role of politicians’ social media accounts in recent disinformation campaigns, from vaccination controversies to voting machine conspiracies, it’s perplexing that a project designed to combat fake news might inadvertently endorse these tactics.

As we confront the urgent need to address the violence of January 8, tackle misinformation, and foster peace in schools, striking a delicate balance is more crucial than ever.

The potential fallout of this bill extends beyond Brazil, as other countries may consider it a model for their own internet regulation efforts. Governments and citizens must resist any attempts to undermine the core values of the digital landscape.

As the debate over Brazil’s “Fake News Bill” continues, it’s vital to maintain a focus on preserving freedom of expression, privacy, and intellectual property rights while ensuring that politicians are held accountable for their actions on social media.