Love In Ancient Rome

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Marriage was regarded as a duty and a means of preserving families. Most marriage were arranged by fathers and set up as alliances between families with producing "legitimate" children as the primary goal. Roman men held marriage in low regard and when they married produced few children. Girls were often forced to marry when they were fourteen. It was not uncommon for a man to marry and divorce several time for his family to work their way up the social ladder. This contempt for marriage kept the population of Rome relatively low while the population of non-Romans and Christians grew.

The marriage customs comprised, first, the ceremony of betrothal (sponsalia), which included the formal consent of the bride's father, and an announcement in the form of a festival or the presentation of the betrothal ring; secondly, the marriage ceremony, which might be either a religious ceremony, in which a consecrated cake was eaten in the presence of the priest (confarreatio), or a secular ceremony, in which the. father gave away his daughter by the forms of a legal sale (coemptio). In the time of the empire it was customary for persons to be married without these ceremonies, by their simple consent, During this time, also, divorces became common and the general morals of society became corrupt. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\]

Marriages were sometimes conducted with a great deal of pomp and ceremony but they were not recognized by the state or a religious body. The only legal matter was that children be "legitimate" to inherit property. The legal-minded Romans developed sophisticated marriage certificates that spelled out the terms of the dowry and how property would be divide in case of divorce or death. The oldest known marriage certificate was a Jewish one found in Egypt and dated to the forth century B.C. It was a contract for an exchange of six cows for a 14-year-old girl.

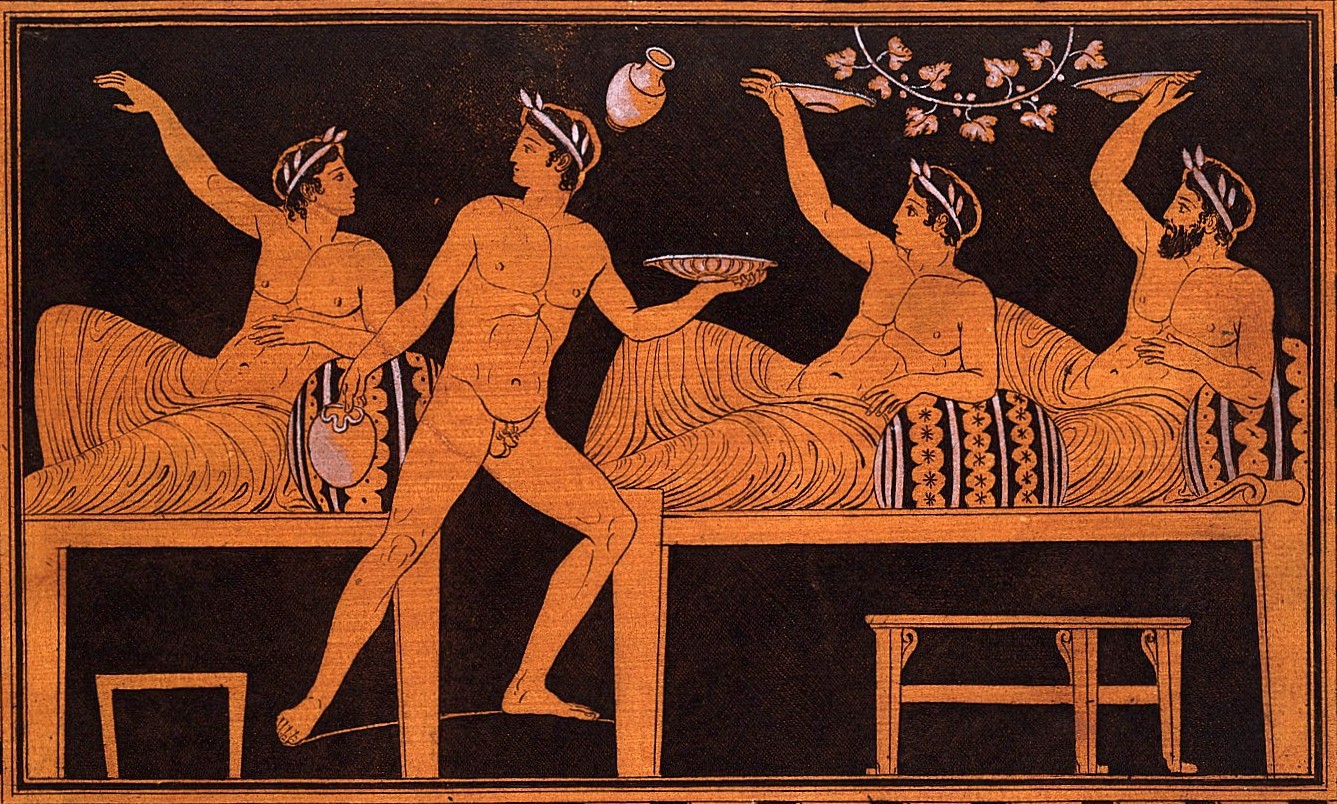

Most people married young: Girls were regarded as ready when they turned 12 and boys when they were 14. Men who were 25 and women who were 20 and still single were penalized. Brides were expected to be virgins. Grooms were expected to have already had some experience with prostitute or slaves. Some children were betrothed at infancy.

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “ Roman marriages were quick and easy and most didn't flower from romance but from two agreements. The first would be between the couple's families, who eyeballed each other to see if the proposed spouse's wealth and social status were acceptable. If satisfied, a formal betrothal took place where a written agreement was signed and the couple kissed. Unlike modern times, the wedding day didn't cement a lawful institution (marriage had no legal power) but showed the couple's intent to live together. A Roman citizen couldn't marry his favorite prostitute, cousin, or, for the most part, non-Romans. A divorce was granted when the couple declared their intention to separate before seven witnesses. If a divorce carried the accusation that the wife had been unfaithful, she could never marry again. A guilty husband received no such penalty."[Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016 ><]

Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; “Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

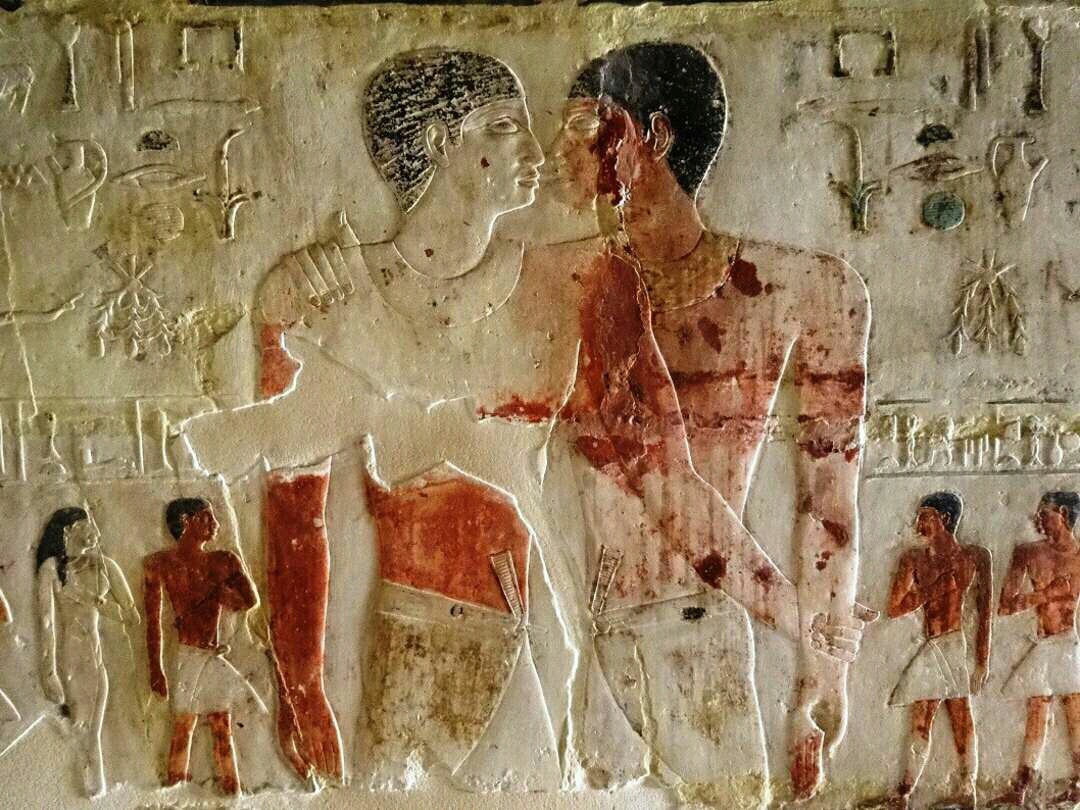

Pompeii couple Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “Polygamy was never sanctioned at Rome, and we are told that for five centuries after the founding of the city divorce was entirely unknown. Up to the time of the Servian constitution (traditional date, sixth century B.C.) patricians were the only citizens and intermarried only with patricians and with members of surrounding communities having like social standing. The only form of marriage known to them was called confarreatio. With the consent of the gods, while the pontifices celebrated the solemn rites, in the presence of the accredited representatives of his gens, the patrician took his wife from her father's family into his own, to be a mater familias, to bear him children who should conserve the family mysteries, perpetuate his ancient race, and extend the power of Rome. By this, the one legal form of marriage of the time, the wife passed in manum viri, and the husband acquired over her practically the same rights as he would have over his own children and other dependent members of his family. Such a marriage was said to be cum conventione uxoris in manum viri. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“During this period, too, the free non-citizens, the plebeians, had been busy in marrying and giving in marriage. There is little doubt that their unions had been as sacred in their eyes, their family ties as strictly regarded and as pure as those of the patricians, but these unions were unhallowed by the national gods and unrecognized by the civil law, simply because the plebeians were not yet citizens. Their form of marriage, called usus, consisted essentially in the living together continuously of the man and woman as husband and wife, though there were probably conventional forms and observances, about which we know absolutely nothing. The plebeian husband might acquire the same rights over the person and property of his wife as the patrician, but the form of marriage did not in itself involve manus. The wife might remain a member of her father's family and retain such property as he allowed her by merely absenting herself from her husband for the space of a trinoctium, that is, three nights in succession, each year.1 If she did this, the marriage was sine conventione in manum, and the husband had no control over her property; if she did not, the marriage, like that of the patricians, was cum conventione in manum. |+|

“Another Roman form of marriage goes at least as far back as the time of Servius. This was also plebeian, though not so ancient as usus. It was called coemptio and was a fictitious sale, by which the pater familias of the woman, or her tutor, if she was subject to one, transferred her to the man matrimonii causa. This form must have been a survival of the old custom of purchase and sale of wives, but we do not know when it was introduced among the Romans. It carried manus with it as a matter of course, and seems to have been regarded socially as better form than usus. The two existed for centuries side by side, but coemptio survived usus as a form of marriage cum conventione in manum." |+|

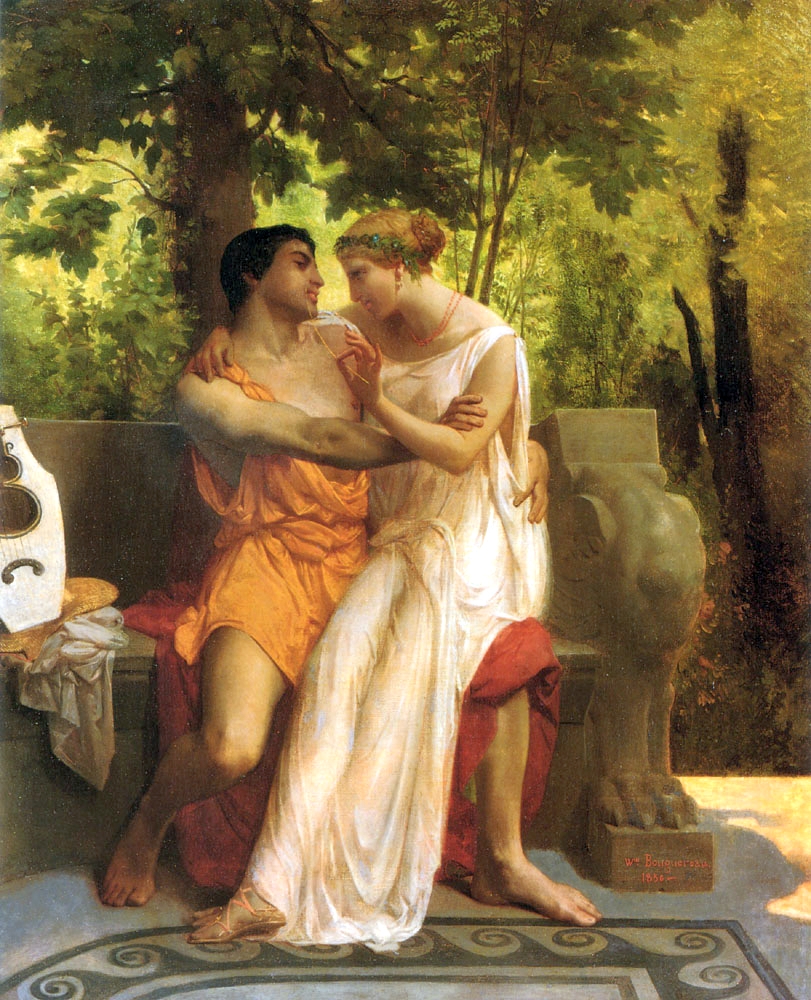

In the view of C.S. Lewis and some other scholars, romantic love did not emerge until relatively late, surfacing in the poems of French and Italian troubadours in the 11th and 12th centuries. But this theory does not seem to be born in evidence from Rome, where lovers were often described in myths and many poems and pieces of graffiti were expressions of love. One graffiti message went: “ ”Lovers, like bees, lead a honeyed life."

The most famous love poets in Rome were the naughty Catulus, the romantics Tibullus and Propertius, the epic Virgil and the love laborer Ovid.

Many pieces of love-related graffiti seem to have been written by love-struck young men. “ ”Girl," reads an inscription found in a Pompeii bedroom, “ ”you're beautiful I've been sent to you by one who is yours." Others express missing a loved one in timeless fashion. “ ”Vibius Restitutus slept here alone, longing for Urbana." Others expressed urgency. “ ”Driver," one said. “ ”If you could feel the fires of love, you would hurry more to enjoy the pleasures of Venus. I love a younger charmer, please spur on the horses, let's get on."

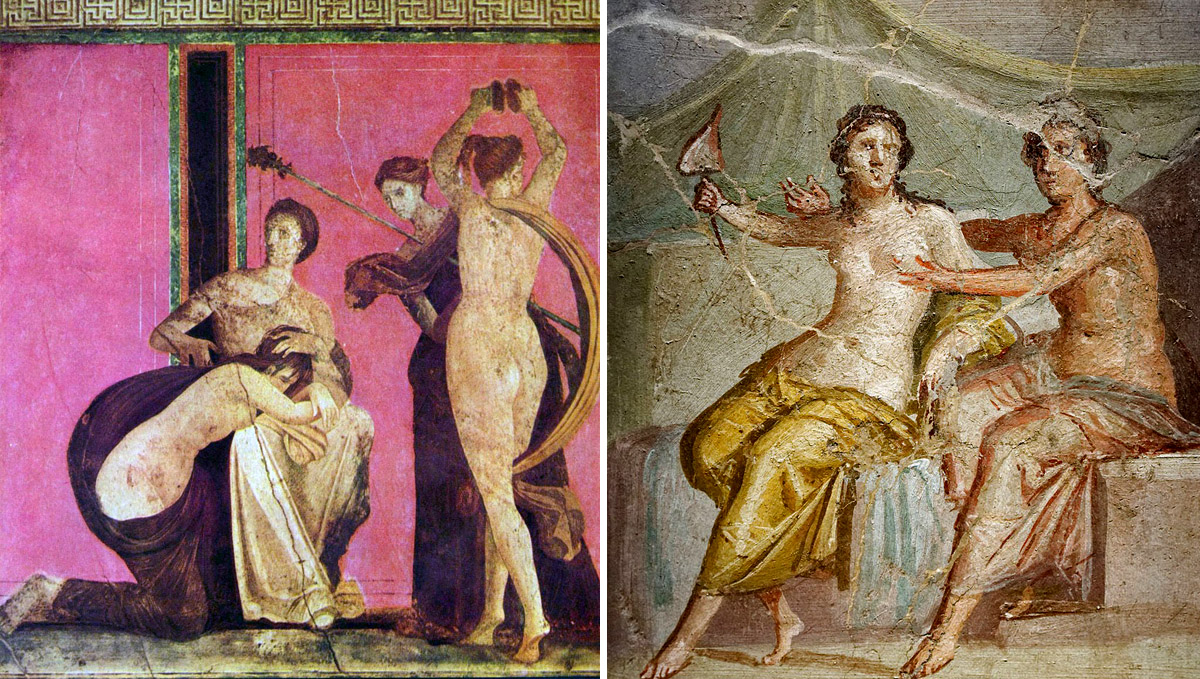

Erotic love was seen by some Greeks and Romans it seems as an accursed thing that attacked its victims in painful, suffering way...and could even kill them. . The A.D. 2nd century physician Galen spent a great amount of time, refuting a popular idea that erotic seizures are caused by the attack of a god who holds burning torches to the victim."

Ovid is regarded as the premier Roman love poet. Brought up in the province to an equestrian family, he moved to Rome as a teenager and wrote about the sensuous life he enjoyed in upper class Roman society. Famed as a kind of Roman Casanova, he married three times, had a great many lovers and was involved in a highly-publicized sex scandal.

Ovid once wrote, "Offered a sexless heaven, I'd say no thank you, women are such sweet hell." He wrote that he learned about love from the mysterious Corinna who he rhapsodized about in his early Loves . As a teenager he wrote they were "two adolescents, exploring a booby-trapped world of adult passions and temptations, and playing private games, first with their society, then--- liaisons dangeruses “ ”with one another."

Ovid was also a great storyteller. His Metamorphosis told the story of the Greek gods in a Roman context. He also poked fun of them. His irreverence helped led to the tossing of the Greek gods and replacing them with Roman ones. Ovid originated many versions of the myth stories we know today such as the King Midas, golden touch tale.

In the Art of Love , a carefully crafted "seducer's manual," Ovid wrote:

Love is a kind of war, and no assignment for cowards.

Where those banners fly, heroes are always on guard.

Soft, those barracks? They know long marches, terrible weather.

Night and winter and storm, grief and excessive fatigue.

Often the rain pelts down from the drenching cloudbursts of heaven.

Often you lie on the ground, wrapped in a mantle of cold.

If you are ever caught, no matter how well you've concealed it.

Though it is clear as the day, swear up and down it's a lie.

Don't be too abject, and don't be too unduly attentive.

That would establish your guilt far beyond anything else.

Wear yourself out if you must, and prove, in her bed, that you could not

Possibly be that good, coming from some other girl.

One wife wrote her husband, who was away: "Send for me---if you don't I'll die without seeing you daily. How I wish I could fly and come to see you...It tortures me not to see you."

Another wife, whose husband had entered a sanctuary wrote him: "When I received your letter...in which you announce that you have become a recluse in the Sarapis temple at Memphis, I immediately thanked the gods that you are well, but you are not coming here when all other recluses have come home, I do not like this one bit."

David Konstan, a classic professor at Brown University, told U.S. News and World Report: “ ”It was taken for granted that if the husband and wife treated each other properly, love would develop and emerge, and by the end of their lives it would be a deep, mutual feeling." Displays of affection however were regarded with soem scorn. One senator was stripped of his seat because he embraced his wife in public.

On one epitaph a man wrote to his wife, apparently thanking her for help escaping capture for some crime: “You furnished most ample means for my escape. With your jewels you aided me when you took off all the gold and pearls from your person, and gave them over to me. And promptly, with slaves, money, and provisions, having cleverly deceived the enemies’ guards, you enriched my absence."

Between Venus and Bacchus

by Alma-TademaHarold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: Though the Servian constitution made the plebeians citizens and thereby legalized their forms of marriage, it did not give them the right of intermarriage with the patricians. Many of the plebeian families were hardly less ancient than the patricians, many were rich and powerful, but it was not until 445 B.C. that marriages between the two Orders were formally sanctioned by the civil law. The objection on the part of the patricians was largely a religious one: the gods of the State were gods of the patricians, the auspices could be taken by patricians only, the marriages of patricians only were sanctioned by heaven. Their orators protested that the unions of the plebeians were not marriages at all, not iustae nuptiae; the plebeian wife, they insisted, was only taken in matrimonium: she was at best only an uxor, not a mater familias; her offspring were “mother's children," not patricii. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“Much of this was class exaggeration, but it is true that for a long time the gens was not so highly valued by the plebeians as by the patricians, and that the plebeians assigned to cognates certain duties and privileges that devolved upon the patrician gentiles. With the extension of the ius conubii many of these points of difference disappeared. New conditions were fixed for iustae nuptiae; coemptio by a sort of compromise became the usual form of marriage when one of the parties was a plebeian; and the stigma disappeared from the word matrimonium. On the other hand, patrician women learned to understand the advantages of a marriage sine conventione in manum, and marriage with manus grew less frequent, the taking of the auspices before the ceremony came to be considered a mere form, and marriage began to lose its sacramental character. With these changes came later the laxness in the marital relation and the freedom of divorce that seemed in the time of Augustus to threaten the very life of the commonwealth. |+|

“It is probable that by the time of Cicero marriage with manus was uncommon, and consequently that confarreatio and coemptio had gone out of general use. To a limited extent, however, the former was retained into Christian times, because certain priestly offices (those of the flamines maiores and the reges sacrorum) could be filled only by persons whose parents had been married by the confarreate ceremony, the sacramental form, and who had themselves been married by the same form. Augustus offered exemption from manus to mothers of three children, but this was not enough, for so great became the reluctance of women to submit to manus that in order to fill even these few priestly offices it was found necessary under Tiberius to eliminate manus from the confarreate ceremony. |+|

Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “There were certain conditions that had to be satisfied before a legal marriage could be contracted even by citizens. The requirements were as follows: 1) The consent of both parties should be given, or that of the pater familias if one or both were in patria potestate. Under Augustus it was provided that the pater familias should not withhold his consent unless he could show valid reasons for doing so. 2) Both of the parties should be puberes; there could be no marriage between children. Although no precise age was fixed by law, it is probable that fourteen and twelve were the lowest limit for the man and the woman respectively. 3) Both man and woman should be unmarried. Polygamy was never sanctioned at Rome. 4) The parties should not be nearly related. The restrictions in this direction were fixed by public opinion rather than by law and varied greatly at different times, becoming gradually less severe. In general it may be said that marriage was absolutely forbidden between ascendants and descendants, between other cognates within the sixth (later the fourth) degree, and between the nearer adfines. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“If the parties could satisfy these conditions, they might be legally married, but distinctions were still made that affected the civil status of the children, although no doubt was cast upon their legitimacy or upon the moral character of their parents. If the conditions were fulfilled and the husband and wife were both Roman citizens, their marriage was called iustae nuptiae, which we may translate by “regular marriage." The children of such a marriage were iusti liberi and were by birth cives optimo iure, “possessed of all civil rights."

“If one of the parties was a Roman citizen and the other a member of a community having the ius conubii but not full Roman civitas, the marriage was still called iustae nuptiae, but the children took the civil standing of the father. This means that, if the father was a citizen and the mother a foreigner, the children were citizens, but, if the father was a foreigner and the mother a citizen, the children were foreigners (peregrini), as was their father. |+|

“But if either of the parties was without the ius conubii, the marriage, though still legal, was called iniustae nuptiae or iniustum matrimonium, “an irregular marriage," and the children, though legitimate, took the civil position of the parent of lower degree. We seem to have something analogous to this today in the loss of social standing which usually follows the marriage of one person with another of distinctly inferior position." |+|

Pompeii silverIn attempt to boost the declining birth rate Augustus, in the A.D. 1st century, offered tax breaks for large families and cracked down on abortion. He imposed strict marriage laws and changed adultery from an act of indecency to an act of sedition, decreeing that a man who discovered his wife's infidelity must turn her in or face charges himself. Adulterous couples could have their property confiscated, be exiled to different parts of the empire and be prohibited from marrying one another. Augustus passed the reforms because he believed that too many men spent their energy with prostitutes and concubines and had nothing for their wives, causing population declines.

Under Augustus, women had the right to divorce. Husbands could see prostitutes but not keep mistresses, widows were obligated to remarry within two years, divorcees within 18 months. Parents with three or more children were given reward

Sexuality in ancient Rome - Wikipedia

MARRIAGE, WEDDINGS AND LOVE IN ANCIENT ROME | Facts and Details

What Sex Was Like in Ancient Rome | by Sal | Lessons from History | Medium

Love in ancient Rome : Grimal, Pierre, 1912- : Free... : Internet Archive

72 Best love Ancient Rome ( 753 BC - 476 AD) images | Ancient rome...

Butt Plug And Spanking

Sexy Crossdresser Pic

Coffee And A Blowjob

Love In Ancient Rome

_(detail)_900x1200.jpg)

.jpg)