Localist commentator Lewis Loud carries on writing despite the National Security Law

Translated by Guardians of Hong Kong

With the publication of his new book declined and feeling watched by ‘invisible state police’ - how will localist commentator Lewis Loud carry on writing?

On 30 June, the National Security Law was passed. People in the city spoke and wrote at their own risk. Political figures left Hong Kong. Slogans on Facebook became symbols. Lyrics to songs were turned into numbers. Column writers announced indefinite suspension of their columns.

Lewis Loud has been publishing political commentary on his blog for more than 10 years. Since the passing of the law, he feels “as if a member of the state police is in front of him” every time he picks up his pen. His new book on China’s and Hong Kong’s history was put on hold because the publisher had suddenly decided not to publish.

When opinions on the internet can be used as evidence in court, does one continue writing? If people can no longer be themselves one day, is it time to leave?

“I am afraid of death. I am afraid of being arrested. I am scared of being abducted to China by national security police. If you hold me at gunpoint, I may very well shut up, just so I can survive” Lewis admitted. “But there is something that has not changed in my heart. It really won’t change. You can’t help it.”

“If I stop writing about politics one day, that’s when you’ll know someone has got me by the balls,” he laughed.

But before that, “I will write until the very end,” he said.

*****************

The new book that has gone unpublished

Not long after the National Security Law passed, Loud was informed that the publisher had ceased printing his book. His publication would be suspended.

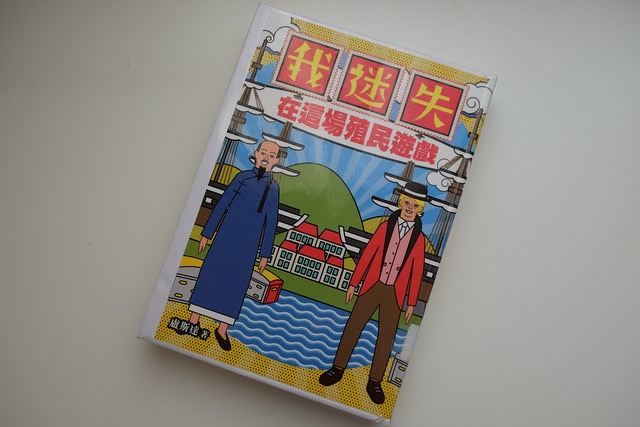

Loud described his new book as “not having a trace of threat to national security”. It describes the history of China from prehistoric times to the Kuomintang era, and addresses the origins of Hong Kong localism. Having studied history in university, Loud hoped to provide an alternate view of Chinese history alongside the official view.

He could never imagine that he could not publish his book. “I feel I used to be more radical in the past yet still I could publish a book back then. So why can I not publish now?” Despite being openly “very fxxking radical”, his previous works, published by Ming Pao, were never met with any intervention or amendment. They are still on the shelves in public libraries and are not even re-assessed for appropriateness.

However, Loud stressed multiple times that publishing is only of “sentimental value” to him and so he “wasn’t particularly disappointed”. Furthermore, in the era of internet, spreading opinions are easy. One needs not write a book.

Some encouraged him to publish in Taiwan. But Loud feels that the issue is not whether he can publish in Taiwan. What concerns him is the publishing industry itself, or that Hong Kongers have to guess where the hypothetical “red line” (i.e. bottom line) is drawn even before the government has enforced the National Security Law. “Freedom of speech is restricted even further. But the freedom is not narrowed by criticism or someone burning down the publishing firm. It is narrowed simply out of fear and self-preservation.”

What he wished not to see is the National Security Law “shaping culture”. “It is not just about a deterrent effect. It is through the deterrence that a culture of self-censorship is created. This damage to Hong Kong will be permanent.”

The invisible national security police watching him writing

But the deterrent is real. The fear is also real. After the passing of the National Security Law, Loud received “kind reminders” from mainland China implying that if he continued to write, he might breach the law. “Of course they were not aggressive or angry on the face. But you feel being closely watched. This insight is causing fear.”

He also admitted, “(Nowadays) Every time I write, whether long or short pieces, I will feel like there is national security police sitting in front of me. Then I will censor myself once. Will this get me into trouble? It means every time I write I encounter internal conflict. You can feel that the law is really shifting culture. Once the invisible national security police comes out, you will be affected.”

When he thought about the once seemingly far-away “speech crime” might become a reality in Hong Kong, Loud was open about it, “I don’t know how to face it. Because... I’ve always thought for 29 years that surely bullshitting would not be a crime. It’s just bullshitting. At the most, people may criticise you for all talk and no action. So you are not supposed to expect legal consequence unless you are defaming someone.”

But in this era, you can be charged for just being a “keyboard warrior”. Loud said this totally contradicts his understanding of freedom of speech. “If you are not allowed to say something, will it eventually get to a point where you could be incriminated by your thoughts? So if I have thought about something, or believed something in the past, or if I still believe in something, will I (be incriminated)?”

“In the past only the pan-democrats, liberal elites, ‘hot dogs’* would criticise me. Now I am suddenly facing a political regime or country threatening me not to talk. This is the first time (experiencing this). I am mind-fucked. I never imagined this.” He shook his head with a bitter smile. [*“Hot dog” is the pejorative term for members of the “Civic Passion” populist political party]

To submit or not— Is there a difference?

When sentencing to ‘speech prison’ can happen anytime, has he thought of stopping? “I really cannot visualise it,” Loud answered without hesitation. “As I have been writing on the internet for more than 10 years, my life is basically linked to current affairs and politics. I cannot imagine a life where I don’t write.”

Not to mention, is it safe even if one stops writing? “The worst thing is that even if you repent, that doesn’t mean China will let you live. Just look at Edward Leung. He signed the confirmation form in order to run for election at the Legislative Council, but still he could not escape the fate of disqualification.” Loud realised that, “bowing before a butcher means you are asking to be shamed for one more time before your death.”

When even Joshua Wong and Martin Lee are seen as pro-independent figures, Loud is clear on the fact that the regime suppresses a person not because of what he or she does, but because of the political effect. “You can step on its tail in so many places. You simply cannot guess what they will do next.”

“Of course it will be dangerous to continue writing,” he paused. “But the problem is that living in a world under China’s influence will be inherently dangerous - you will never be a hundred-percent safe.”

*******************

Between self-sacrificing hero and staying in the comfort zone - make sure you can face yourself and others

After careful considerations, he decided to carry on writing. Having written about politics on his online column for more than 10 years, the freedom to express is where the fundamental dignity of a person lies. It is also a social responsibility.

“Do you think I enjoy writing about these topics? In reality, following politics itself is not healthy,” Loud sighed. To some extent, the reason he continues to write is to offer a contrasting voice to those on major media and those of politicians. “I want to fight for my own dignity as well as people of my age.” After the passing of the law, he said he already “passed his peak” and comparatively his words are now “very mild”. However after repeated consideration, he was still unable to amend what he has already written. “So I just leave it as is.”

As a “localist author”, would he be likely to commit the crimes of secession or subversion? “Sometimes I will be less direct. Of course, I am obeying the authorities by the book,” Loud admitted. For example, he could not directly mention “those four words”, but apart from “those four words”, Loud feels there is still much to say.

“I think slogans are important. Isn’t it enough for everyone in Hong Kong to be shouting ‘liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times’?” He highlighted that while society had a common hope for the future, he could still write about topics as a brainstorming resource for others, for example, reconstructing the understanding of history. He could still carry on using other platforms to convince others, “In the end, I will still talk about the identity of Hongkongers.”

Therefore, the problem may not be whether to submit to power. “I am not truly a self-sacrificing hero. But I don’t totally stay in my comfort zone. I know people aren’t these two types either. Most people are in the middle,” Loud was being frank. “I think we all have a responsibility to find ‘a way of living’ by which we can maintain our integrity. You won’t say you are useless because you submit to authority. But, at the same time, you won’t say you sacrifice for no purpose.”

To this end, how do we choose to face this evil world? “I can only try my best...to preserve myself. Of course, I am scared. But I try not to spread fear.”

Loud reckons it is acceptable for those public figures “on the big screen” to panic. The most important thing is that those who helped to create these public figures “behind the screen” were not deterred by the law. “I will comfort the others and say you are okay as you are not on the top of the list. You are much safer than me. And I am much safer than Joshua Wong.”

“It will be a pity…”

Just like anyone facing political risk, when the National Security Law was passed, Loud’s family and friends asked whether he would leave Hong Kong. Loud said he had no desire to leave. Firstly, even if he left, it did not guarantee safety. Secondly, he did not want to lose touch with Hong Kong.

“The physical environment in Hong Kong is the inspiration my writing. Once I lose it, I will enter the ‘student movement status’ (referring to those student leaders in exile after the Tiananmen massacre). I don’t want to,” he said but he had to admit, “sometimes just physically being in Hong Kong qualifies you to speak out.”

Where did this nostalgia towards Hong Kong come from? Loud said he never had any sense of belonging to any group since young. But the first time he found a sense of belonging was with the localists. At first, it might be the feeling of ‘facing the humiliation from mainland China together’ and ‘being oppressed together’. But slowly it transformed into an emotional attachment to Hong Kong.”

In recent years, he witnessed the rise and fall of localism and he was a part of it. If he leaves now and never comes back, “I would feel that the last several years... would disappear. Or the experience we gained in common would cease to exist.”

“It will be a pity,” he added with a frown.

Laugh till the end in the worst of times

Regarding the future of Hong Kong, Loud said while the situation is indeed dire, he remains optimistic for the long run. “When I was young, I used to think back then Hong Kong was so fxxking hopeless,” he laughed. He described the psychological resilience of Hongkongers now as vastly different to that of the past. The new generation who lived “without any remnants of the peaceful delusion from the colonial era” and they grew up in turbulent times. “The rate at which Hongkongers change their mindset will also be quicker.”

Some might think that fighting for any demand at all in Hong Kong is no longer feasible. “If that’s how you think, then you don’t have to lift a finger. You life will wilt anyway, right?” Loud laughed. “Of course there is always something in life that is very difficult to achieve. But you still work towards it anyway regardless. I think this is the basic outlook we have.”

So, in the new era, “the most important thing is... not to die. Drink more water, right?” Loud was dead serious. After all, “whoever has the last laugh will be the one to define Hong Kong”.

Source: inMedia HK (Text and photos)

Journalist: Wong Yui-hin

https://www.inmediahk.net/node/1075843