Linear algebra for game developers: Part I

Games Development

I decided if I'm going to write about linear algebra, I might as well start at the beginning! This will be review to many of you who have written games before or taken classes in kinematic physics, so please bear with me for this introductory post -- I will get to more advanced topics later.

Why do we care about linear algebra?

Linear algebra is the study of vectors. If your game involves the position of an on-screen button, the direction of a camera, or the velocity of a race car, you will have to use vectors. The better you understand linear algebra, the more control you will have over the behavior of these vectors.

What is a vector?

In games, vectors are used to store positions, directions, and velocities. Here are some 2-Dimensional examples:

The position vector indicates that the man is standing two meters east of the origin, and one meter north. The velocity vector shows that in one minute, the plane moves three kilometers up, and two to the left. The direction vector tells us that the pistol is pointing to the right.

As you can see, a vector by itself is just a set of numbers -- it is only given meaning by its context. For example, the vector (1,0) could be the direction for the gun as shown, but it could also be the position of a building one mile to the east of your current position, or the velocity of a snail moving right at a speed of 1 mph.

For this reason, it's important to keep track of your units. Let's say we have a vector V (3,5,2). This doesn't mean much by itself. Three what? Five what? In Overgrowth, positions are always given in meters, and velocities in meters per second. The first number is east, the second is up, and the third is north. Negative numbers represent the opposite directions: west, down, and south. The position represented by (3,5,2) is 3 meters east, 5 meters up, and 2 meters north, as shown here:

Now that we've gone over the basics of vectors, we need to know how to use them.

Vector addition

To add vectors together, you just add each component together separately. For example:

(0,1,4) + (3,-2,5) = (0+3, 1-2, 4+5) = (3,-1,9)

Why do we want to add vectors together? One of the most common applications in games for vector addition is physics integration. Any physically-based object will likely have vectors for position, velocity, and acceleration. For every frame (usually 1/60th of a second), we have to integrate these vectors -- that is, add the velocity to the position, and the acceleration to the velocity.

Let's consider the example of Mario jumping. He starts at position (0,0). As he starts the jump, his velocity is (1,3) -- he is moving upwards quickly, but also to the right. His acceleration throughout is (0,-1), because gravity is pulling him downwards. Here is what his jump looks like over the course of seven more frames. The black text specifies his velocity for each frame.

We can walk through the first couple frames by hand to see how this works.

For the first frame, we add his velocity (1,3) to his position (0,0) to get his new position (1,3). Then, we add his acceleration (0,-1) to his velocity (1,3) to get his new velocity (1,2).

We do it again for the second frame. We add his velocity (1,2) to his position (1,3) to get (2,5). Then, we add his acceleration (0,-1) to his velocity (1,2) to get (1,1).

Usually in games the player controls a character's acceleration with the keyboard or gamepad, and the game calculates the new velocity and position using physics integration (via vector addition). Fun fact: this is the same kind of integration problem that you solve using integral calculus - we are just using an approximate brute-force approach. I found it much easier to pay attention to calculus classes by thinking about physical applications like this.

Vector subtraction

Subtraction works in the same way as addition -- subtracting one component at a time. Vector subtraction is useful for getting a vector that points from one position to another. For example, let's say the player is standing at (1,2) with a laser rifle, and an enemy robot is at (4,3). To get the vector that the laser must travel to hit the robot, you can subtract the player's position from the robot's position. This gives us:

(4,3)-(1,2) = (4-1, 3-2) = (3,1).

Scalar-vector multiplication

When we talk about vectors, we refer to individual numbers as scalars. For example, (3,4) is a vector, 5 is a scalar. In games, it is often useful to multiply a vector by a scalar. For example, we can simulate basic air resistance by multiplying the player's velocity by 0.9 every frame. To do this, we just multiply each component of the vector by the scalar. If the player's velocity is (10,20), the new velocity is:

0.9*(10,20) = (0.9*10, 0.9*20) = (9,18).

Length

If we have a ship with velocity vector V (4,3), we might also want to know how fast it is going, in order to calculate how much the screen should shake or how much fuel it should use. To do that, we need to find the length (or magnitude) of vector V. The length of a vector is often written using || for short, so the length of V is |V|.

We can think of V as a right triangle with sides 4 and 3, and use the Pythagorean theorem to find the hypotenuse: x2 + y2 = h2. That is, the length of a vector H with components (x,y) is sqrt(x2+y2). So, to calculate the speed of our ship, we just use:

|V| = sqrt(42+32) = sqrt(25) = 5

This works with 3D vectors as well -- the length of a vector with components (x,y,z) is sqrt(x2+y2+z2).

Distance

If the player P is at (3,3) and there is an explosion E at (1,2), we need to find the distance between them to see how much damage the player takes. This is easy to find by combining two tools we have already gone over: subtraction and length. We subtract P-E to get the vector between them, and then find the length of this vector to get the distance between them. The order doesn't matter here, |E-P| will give us the same result.

Distance = |P-E| = |(3,3)-(1,2)| = |(2,1)| = sqrt(22+12) = sqrt(5) = 2.23

Normalization

When we are dealing with directions (as opposed to positions or velocities), it is important that they have unit length (length of 1). This makes life a lot easier for us. For example, let's say there is a gun pointing in the direction of (1,0) that shoots a bullet at 20 m/s. What is the velocity of the bullet? Since the direction has length 1, we can just multiply the direction and the bullet speed to get the bullet velocity: (20,0). If the direction vector had any other length, we couldn't do this -- the bullet would be too fast or too slow.

A vector with a length of 1 is called "normalized". So how do we normalize a vector (set its length to 1)? Easy, we divide each component by the vector's length. If we want to normalize vector V with components (3,4), we just divide each component by its length, 5, to get (3/5, 4/5). Now we can use the pythagorean theorem to prove that it has length 1:

(3/5)2 + (4/5)2 = 9/25 + 16/25 = 25/25 = 1

Dot product

What is the dot product (written •)? Let's hold off on that for a second, and look at how we calculate it. To get the dot product of two vectors, we multiply the components, and then add them together.

(a1,a2)•(b1,b2) = a1b1 + a2b2

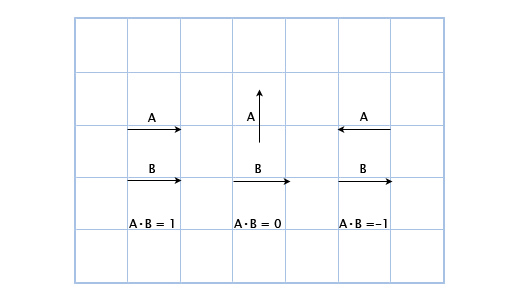

For example, (3,2)•(1,4) = 3*1 + 2*4 = 11. This seems kind of useless at first, but lets look at a few examples:

Here, we can see that when the vectors are pointing the same direction, the dot product is positive. When they are perpendicular, the dot product is zero, and when they point in opposite directions, it is negative. Basically, it is proportional to how much the vectors are pointing in the same direction. This is a small taste of the power of the dot product, and it's already pretty useful!

Let's say we have a guard at position G (1,3) facing in the direction D (1,1), with a 180 field of view. We have a hero sneaking by at position H (3,2). Is he in the guard's field of view? We can find out by checking the sign of the dotproduct of D and V (the vector from the guard to the hero). This gives us:

V = H-G = (3,2)-(1,3) = (3-1,2-3) = (2,-1)

D•V = (1,1)•(2,-1) = 1*2+1*-1 = 2-1 = 1

Since 1 is positive, the hero is in the guard's field of view!

We know that the dot product is related to the extent to which the vectors are pointing in the same direction, but what is the exact relation? It turns out that the exact equation for the dot product is:

AB = |A||B|cosθ

Where θ (pronounced "theta") is the angle between A and B. This allows us to solve for θ if we want to find out the angle:

θ = acos([AB]/[|A||B|]).

As I mentioned before, normalizing vectors makes our life easier! If A and B are normalized, then the equation is simply:

θ = acos(AB)

Let's revisit the guard scenario above, except the guard's field of view is only 120. First, we get the normalized vectors for the direction the guard is facing (D'), and the direction from the guard to the hero (V'). Then, we check the angle between them. If it is greater than 60 (half of the field of view), then the hero is not seen.

D' = D/|D| = (1,1)/sqrt(12+12) = (1,1)/sqrt(2) = (0.71,0.71)

V' = V/|V| = (2,-1)/sqrt(22+(-1)2) = (2,-1)/sqrt(5) = (0.89,-0.45)θ = acos(D'V') = acos(0.71*0.89 + 0.71*(-0.45)) = acos(0.31) = 72

The angle between the center of the guard's vision and the hero is 72, so the guard does not see him!

I know this looks like a lot of work, and it is, because I'm doing it by hand. However, in a program, this is pretty simple. Here is what this would like in Overgrowth using the C++ vector libraries I wrote (inspired by GLSL syntax).

//Initialize starting vectors

vec2 guard_pos = vec2(1,3);

vec2 guard_facing = vec2(1,1);

vec2 hero_pos = vec2(3,2);

//Prepare normalized vectors

vec2 guard_facing_n = normalize(guard_facing);

vec2 guard_to_hero = normalize(hero_pos - guard_pos);

//Check angle

float angle = acos(dot(guard_facing_n, guard_to_hero));

Cross Product

Let's say you have a boat that has cannons that fire to the left and right. Given that the boat is facing along the direction vector (2,1), in which directions do the cannons fire? This is easy in 2D: to rotate 90 degrees clockwise, just flip the two vector components, and then switch the sign of the second component. (a,b) becomes (b,-a). So, if the boat is facing along (2,1), the right-facing cannons fire towards (1,-2). The left-facing cannons fire in the opposite direction, so we flip both signs to get: (-1,2).

So, what if we want to do this in 3D? Let's revisit our sailing ship. We have a vector for the direction of the mast M, going straight up (0,1,0), and the direction of the north-north-east wind W (1,0,2), and we want to find the direction the sail S should stick out in order to best catch the wind. The sail has to be perpendicular to the mast, and also perpendicular to the wind. To solve this, we can use the cross product: S = M x W.

The cross product of A(a1,a2,a3)) and B(b1,b2,b3)) is:

(a2b3-a3b2, a3b1-a1b3, a1b2-a2b1)

So now we can plug in our numbers and solve our problem:

S = MxW = (0,1,0)x(1,0,2) = ([1*2-0*0], [0*1-0*2], [0*0-1*1]) = (2,0,-1)

This is pretty ugly to do by hand. For most graphics and game work I would recommend just encapsulating it in a function like the one below, and never thinking about the details again.

vec3 cross(vec3 a, vec3 b) {

vec3 result;

result[0] = a[1] * b[2] - a[2] * b[1];

result[1] = a[2] * b[0] - a[0] * b[2];

result[2] = a[0] * b[1] - a[1] * b[0];

return result;

}

Another common use for the cross product in games is to find surface normals -- the direction that a surface is facing. For example, let's take a triangle with vertex vectors A, B and C. How do we find the direction that the triangle is facing? It seems tricky, but we have the tools to do it now. We can use subtraction to get the direction from A to C (C-A) 'Edge 1' and A to B (B-A) 'Edge 2', and then use the cross product to find a new vector N perpendicular to both of them... the surface normal.

Here is what that would like in code:

vec3 GetTriangleNormal(vec3 a, vec3 b, vec3 c) {

vec3 edge1 = b-a;

vec3 edge2 = c-a;

vec3 normal = cross(edge1,edge2);

return normal;

}

Fun fact: the basic expression for lighting in games is just N•L, where N is the surface normal, and L is the normalized light direction. This is what makes surfaces bright when they face towards the light, and dark when they don't.

Thanks for reading, are you still in?

If you enjoyed this article, it would be cool if you press like, or write something to me, it will make me to post more often and more cooler content ;)

Further Reading:

How to launch a side project in 10 days

How to Actually Finish Your First Game?

Top 7 Soft Skills for Developers