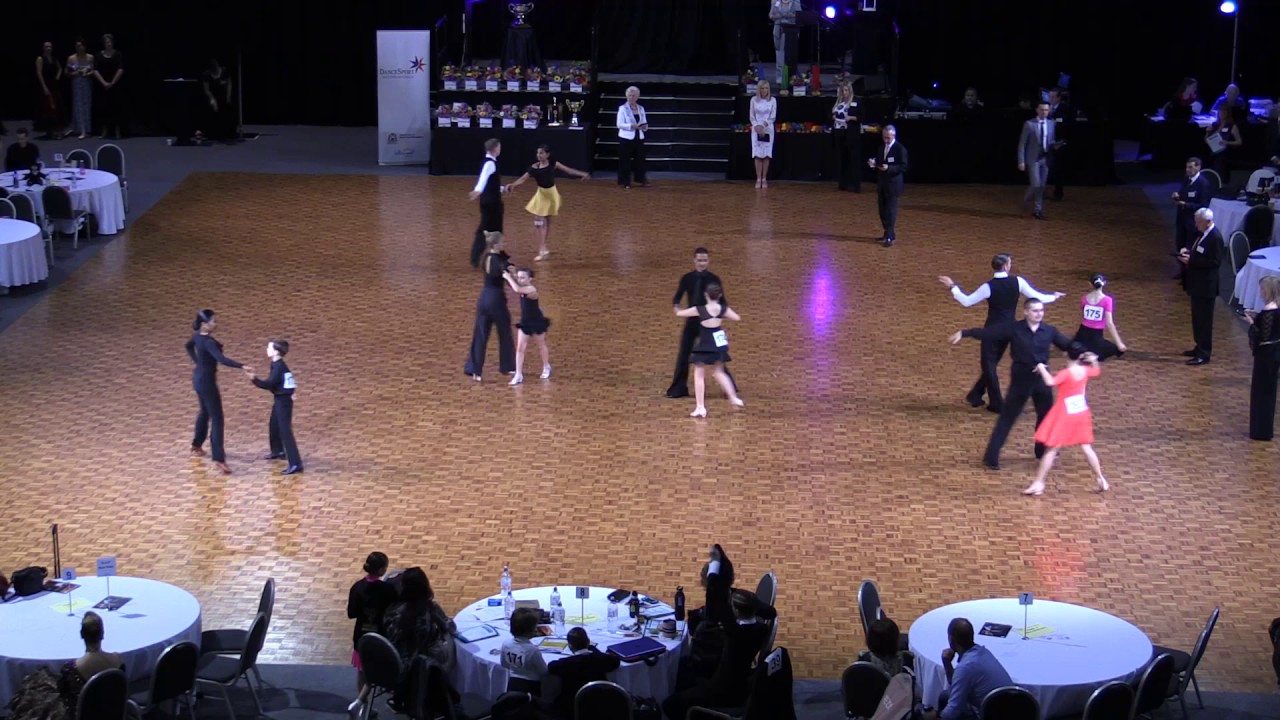

Latin Final

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

https://www.wordhippo.com/what-is/the/latin-word-for-d594c2cc0a53025004791399d80e20852...

Перевести · How to say final in Latin. final. Latin Translation. finalem. More Latin words for final. ultimus adjective. …

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=YoSBu5JBkSc

Перевести · 13.03.2018 · The Latin final of the 2018 WDSF European DanceSport Championship Ten Dance in Brno, CZE, …

Final Latin | 2020 WDSF European Championship Ten Dance in Aarhus

The Final Reel | 2017 WDSF World Open Latin | DanceSportTotal

2013 WDSF World Youth Latin | The Final Reel | DanceSportTotal

2019 WDSF World Open Tokyo | Latin Final | DanceSportTotal

Star | 2019 WDSF World Formation Latin Semi-final

2013 GS Latin Final | The Semi-Final Reel

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=CIwLz8PGiyk

Перевести · 19.03.2017 · Final Latin | 2020 WDSF European Championship …

https://www.wordhippo.com/what-is/the/latin-word-for-cc88d6531c448e2b71d475f129ff...

Перевести · Here's how you say it. Latin Translation. ultimo. More Latin words for finale. exodium noun. finale, interlude, …

https://vk.com/video-50605731_164462534

Saint-Petersburg Open 2013 Adult Latin Final Cha-Cha-Cha Взрослые, латина, финал, ча-ча-ча

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/list_of_latin_phrases_(full)

Перевести · Meaning from out of the depths of misery or dejection. From the Latin translation of the Vulgate Bible of Psalm 130, of which it is a traditional title in Roman Catholic liturgy. de re: about/regarding the …

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vulgar_Latin

Language family: Indo-European, ItalicLatino …

Native to: Roman Empire, Various Roman successors

Writing system: Latin

ISO 639-3: –

Contemporary evidence

The Appendix Probi, dating to about the seventh century AD, is a list of spelling corrections written in the format "[correct form], not [incorrect form]". The mistakes that it mentions hint at ongoing changes in the spoken language, such as:

1. Syncope in unstressed internal syllables:

2. Development of [j] from front vowels in hiatus:

3. Loss of /n/ before /s/:

Many …

Contemporary evidence

The Appendix Probi, dating to about the seventh century AD, is a list of spelling corrections written in the format "[correct form], not [incorrect form]". The mistakes that it mentions hint at ongoing changes in the spoken language, such as:

1. Syncope in unstressed internal syllables:

2. Development of [j] from front vowels in hiatus:

3. Loss of /n/ before /s/:

Many of the 'incorrect' forms survive in modern Romance: the form mesa 'table' explains Spanish mesa and Romanian masă; speclum 'looking-glass' explains Italian specchio and Portuguese espelho; oclus explains Aromanian oclju and Neapolitan uocchio; etc.

Consonant development

The most significant consonant changes affecting Vulgar Latin were palatalization (except in Sardinia); lenition, including simplification of geminate consonants (in areas north and west of the La Spezia–Rimini Line, e.g. Spanish digo vs. Italian dico 'I say', Spanish boca vs. Italian bocca 'mouth'); and loss of final consonants.

Loss of final consonants

The loss of final consonants was underway by the 1st century AD in some areas. A graffito at Pompeii reads "quisque ama valia", which in Classical Latin would read "quisquis amat valeat" ("may whoever loves be strong/do well"). (The change from "valeat" to "valia" is also an early indicator of the development of /j/ (yod), which played such an important part in the development of palatalization.) On the other hand, the loss of final /t/ was not general. Old Spanish and Old French preserved a reflex of final /t/ until 1100 AD or so, Modern French still maintains final /t/ in some liaison environments, and Sardinian retains final /t/ in almost all circumstances.

Lenition of stops

Areas north and west of the La Spezia–Rimini Line lenited intervocalic /p, t, k/ to /b, d, ɡ/. This phenomenon is occasionally attested during the imperial period, but it became frequent by the 7th century. For example, in Merovingian documents, "rotatico" > rodatico ("wheel tax").

Simplification of geminates

Reduction of bisyllabic clusters of identical consonants to a single syllable-initial consonant also typifies Romance north and west of La Spezia-Rimini. The results in Italian and Spanish provide clear illustrations: "siccus" > Italian secco, Spanish seco; "cippus" > Italian ceppo, Spanish cepo; "mittere" > Italian mettere, Spanish meter.

Loss of word-final m

The loss of the final m was a process which seems to have begun by the time of the earliest monuments of the Latin language. The epitaph of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, who died around 150 BC, reads "taurasia cisauna samnio cepit", which in Classical Latin would be "taurāsiam, cisaunam, samnium cēpit" ("He captured Taurasia, Cisauna, and Samnium"). This however can be explained in a different way, that the inscription simply fails to note the nasality of the final vowels (just as consul was customarily abbreviated as "cos").

Neutralization of /b/ and /w/

Confusions between b and v show that the Classical semivowel /w/, and intervocalic /b/ partially merged to become a bilabial fricative /β/ (Classical semivowel /w/ became /β/ in Vulgar Latin, while [β] became an allophone of /b/ in intervocalic position). Already by the 1st century AD, a document by one Eunus writes "iobe" for "iovem" and "dibi" for "divi". In most of the Romance varieties, this sound would further develop into /v/, with the notable exception of the betacist varieties of Hispano-Romance and most Sardinian lects: b and v represent the same phoneme /b/ (with allophone [β]) in Modern Spanish, as well as in Galician, northern Portuguese, several varieties of Occitan and the northern dialects of Catalan.

Consonant cluster simplification

In general, many clusters were simplified in Vulgar Latin. For example, /ns/ reduced to /s/, reflecting the fact that syllable-final /n/ was no longer phonetically consonantal. In some inscriptions, "mensis" > mesis ("month"), or "consul" > cosul ("consul"). Descendants of "mensis" include Portuguese mês, Spanish and Catalan mes, Old French meis (Modern French mois), Italian mese. In some areas (including much of Italy), the clusters [mn], [kt] ⟨ct⟩, [ks] ⟨x⟩ were assimilated to the second element: [nn], [tt], [ss]. Thus, some inscriptions have "omnibus" > onibus ("all [dative plural]"), "indictione" > inditione ("indiction"), "vixit" > bissit ("lived"). Also, three-consonant clusters usually lost the middle element. For example, "emptores" > imtores ("buyers").

Not all areas show the same development of these clusters, however. In the East, Italian has [kt] > [tt], as in "octo" > otto ("eight") or "nocte" > notte ("night"); while Romanian has [kt] > [pt] (opt, noapte). By contrast, in the West, the [k] weakened to [j]. In French and Portuguese, this came to form a diphthong with the previous vowel (huit, oito; nuit, noite), while in Spanish, the [i] brought about palatalization of [t], which produced [tʃ] (*oito > ocho, *noite > noche).

Also, many clusters including [j] were simplified. Several of these groups seem to have never been fully stable (e.g. facunt for "faciunt"). This dropping has resulted in the word "parietem" ("wall") developing as Italian parete, Romanian părete>perete, Portuguese parede, Spanish pared, or French paroi (Old French pareid).

The cluster [kw] ⟨qu⟩ was simplified to [k] in most instances before /i/ and /e/. In 435, one can find the hypercorrective spelling quisquentis for "quiescentis" ("of the person who rests here"). Modern languages have followed this trend, for example Latin "qui" ("who") has become Italian chi and French qui (both /ki/); while "quem" ("whom") became quien (/kjen/) in Spanish and quem (/kẽj/) in Portuguese. However, [kw] has survived in front of [a] in most areas, although not in French; hence Latin "quattuor" yields Spanish cuatro (/kwatro/), Portuguese quatro (/kwatru/), and Italian quattro (/kwattro/), but French quatre (/katʀ/), where the qu- spelling is purely etymological.

In Spanish, most words with consonant clusters in syllable-final position are loanwords from Classical Latin, examples are: transporte [tɾansˈpor.te], transmitir [tɾanz.miˈtir], instalar [ins.taˈlar], constante [konsˈtante], obstante [oβsˈtante], obstruir [oβsˈtɾwir], perspectiva [pers.pekˈti.βa], istmo [ˈist.mo]. A syllable-final position cannot be more than one consonant (one of n, r, l, s or z) in most (or all) dialects in colloquial speech, reflecting Vulgar Latin background. Realizations like [trasˈpor.te], [tɾaz.miˈtir], [is.taˈlar], [kosˈtante], [osˈtante], [osˈtɾwir], and [ˈiz.mo] are very common, and in many cases, they are considered acceptable even in formal speech.

Vowel development

In general, the ten-vowel system of Classical Latin, which relied on phonemic vowel length, was newly modelled into one in which vowel length distinctions lost phonemic importance, and qualitative distinctions of height became more prominent.

System in Classical Latin

Classical Latin had 10 different vowel phonemes, grouped into five pairs of short-long, ⟨ă – ā, ĕ – ē, ĭ – ī, ŏ – ō, ŭ – ū⟩. It also had four diphthongs, ⟨ae, oe, au, eu⟩, and the rare diphthongs ⟨ui, ei⟩. Finally, there were also long and short ⟨y⟩, representing /y/, /yː/ in Greek borrowings, which, however, probably came to be pronounced /i/, /iː/ even before Romance vowel changes started.

At least since the 1st century AD, short vowels (except a) differed by quality as well as by length from their long counterparts, the short vowels being lower. Thus the vowel inventory is usually reconstructed as /a – aː/, /ɛ – eː/, /ɪ – iː/, /ɔ – oː/, /ʊ – uː/.

Monophthongization

Many diphthongs had begun their monophthongization very early. It is presumed that by Republican times, "ae" had become /ɛː/ in unstressed syllables, a phenomenon that would spread to stressed positions around the 1st century AD. From the 2nd century AD, there are instances of spellings with ⟨ĕ⟩ instead of ⟨ae⟩. ⟨oe⟩ was always a rare diphthong in Classical Latin (in Old Latin, oinos regularly became "unus" ("one")) and became /eː/ during early Imperial times. Thus, one can find penam for "poenam".

However, ⟨au⟩ lasted much longer. While it was monophthongized to /o/ in areas of north and central Italy (including Rome), it was retained in most Vulgar Latin, and it survives in modern Romanian (for example, aur < "aurum"). There is evidence in French and Spanish that the monophthongization of au occurred independently in those languages.

Loss of distinctive length and near-close mergers

Length confusions seem to have begun in unstressed vowels, but they were soon generalized. In the 3rd century AD, Sacerdos mentions people's tendency to shorten vowels at the end of a word, while some poets (like Commodian) show inconsistencies between long and short vowels in versification. However, the loss of contrastive length caused only the merger of "ă" and "ā" while the rest of pairs remained distinct in quality: /a/, /ɛ – e/, /ɪ – i/, /ɔ – o/, /ʊ – u/.

Also, the near-close vowels /ɪ/ and /ʊ/ became more open in most varieties and merged with /e/ and /o/ respectively. As a result, the reflexes of Latin pira "pear" and vēra "true" rhyme in most Romance languages: Italian and Spanish pera, vera. Similarly, Latin nucem "walnut" and vōcem "voice" become Italian noce, voce, Portuguese noz, voz.

There was likely some regional variation in pronunciation, as the Romanian languages, Sardinian and African Romance evolved differently. In Sardinian, all corresponding short and long vowels simply merged with each other, creating a 5-vowel system: /a, e, i, o, u/. African Romance appears to have evolved similarly. In Romanian, the front vowels ĕ, ĭ, ē, ī evolved like the Western languages, but the back vowels ŏ, ŭ, ō, ū evolved as in Sardinian. A few Southern Italian languages, such as southern Corsican, northernmost Calabrian and southern Lucanian, behave like Sardinian with its penta-vowel system or, in case of Vegliote (even if only partially) and western Lucanian, like Romanian.

Phonologization of stress

The placement of stress generally did not change from Classical to Vulgar Latin, and except for reassignment of stress on some verb morphology (e.g. Italian cantavamo 'we were singing', but stress retracted one syllable in Spanish cantábamos) most words continued to be stressed on the same syllable they were before. However, the loss of distinctive length disrupted the correlation between syllable weight and stress placement that existed in Classical Latin. Whereas in Classical Latin the place of the accent was predictable from the structure of the word, it was no longer so in Vulgar Latin. Stress had become a phonological property and could serve to distinguish forms that were otherwise homophones of identical phonological structure, as in Spanish canto 'I sing' vs. cantó 'he or she sang'.

Lengthening of stressed open syllables

After the Classical Latin vowel length distinctions were lost in favor of vowel quality, a new system of allophonic vowel quantity appeared sometime between the 4th and 5th centuries. Around then, stressed vowels in open syllables came to be pronounced long (but still keeping height contrasts), and all the rest became short. For example, long venis /*ˈvɛː.nis/, fori /*fɔː.ri/, cathedra /*ˈkaː.te.dra/; but short vendo /*ˈven.do/, formas /*ˈfor.mas/. (This allophonic length distinction persists to this day in Italian.) However, in some regions of Iberia and Gaul, all stressed vowels came to be pronounced long: for example, porta /*ˈpɔːr.ta/, tempus /*ˈtɛːm.pus/. In many descendants, several of the long vowels underwent some form of diphthongization, most extensively in Old French where five of the seven long vowels were affected by breaking.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin_phonology_and_orthography

Перевести · Latin phonology continually evolved over the centuries, making it difficult for speakers in one era to know how Latin was spoken before then. A given phoneme may be represented by different letters in different periods. This article deals primarily with modern scholarship's best reconstruction of Classical Latin…

Amateur Latin Final - Samba - BYU Dancesport Championships 2012 смотреть онлайн

Amateur Latin Final - Rumba - BYU Dancesport Championships 2012 смотреть онлайн

Не удается получить доступ к вашему текущему расположению. Для получения лучших результатов предоставьте Bing доступ к данным о расположении или введите расположение.

Не удается получить доступ к расположению вашего устройства. Для получения лучших результатов введите расположение.

Shawn and Gladys Dance Academy•2,2 млн просмотров

Официальный канал КВН•9,9 млн просмотров

lucasil65 - ProjeSom Eventos•77 млн просмотров

High Heels Crush Vk

Gagging Russia

Hogtied Femdom Gagged

Kinky Vintage Fun Porno

Ficus Kinky

How to say final in Latin - WordHippo

How to say finale in Latin - wordhippo.com

Saint-Petersburg Open 2013 Adult Latin Final.. — Видео ...

List of Latin phrases (full) - Wikipedia

Vulgar Latin - Wikipedia

Latin phonology and orthography - Wikipedia

Amateur Latin Final - Samba - BYU Dancesport Championships ...

Amateur Latin Final - Rumba - BYU Dancesport Championships ...

Latin Final