Latex Label

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

\documentclass { article }

\usepackage { float }

\usepackage { graphicx }

\usepackage { caption }

\usepackage { subcaption }

\usepackage { hyperref }

\begin { document }

We can describe atoms through use of the Schr \" { o } dinger

equation which is given as

\begin { equation }

\label { schro }

E \Psi = \textbf { H } \Psi .

\end { equation }

If we carry out equation \ref { schro } to its fullest consequences,

we can describe figure \ref { fig:Atoms } .

\begin { figure }

\centering

\begin { subfigure }{ .45 \textwidth }

\centering

\includegraphics [width=\textwidth] { atom.png }

\caption { Big atoms }

\label { subfig:big }

\end { subfigure }

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

\begin { subfigure }{ .45 \textwidth }

\centering

\includegraphics [scale=.25] { atom.png }

\caption { Small atom }

\label { subfig:small }

\end { subfigure }

\caption { Atoms }

\label { fig:Atoms }

\end { figure }

We also can use this to describe the atomic masses of

elements from big, \ref { subfig:big } , to small, \ref { subfig:small } .

Some of these masses are given in table \ref { tab:atommass } .

\begin { table } [H]

\centering

\begin { tabular }{ c|c }

Element & Atomic Mass (amu) \\\hline

H & 1.007 825 032 07(10 \\

He & 3.016 029 3191(26) \\

Li & 6.015 122 795(16) \\

Be & 9.012 182 2(4) \\

B & 10.012 937 0(4) \\

C & 12.000 000 0(0)

\end { tabular }

\caption { Atomic Masses }

\label { tab:atommass }

\end { table }

We don't have a \ref { noref }

\end { document }

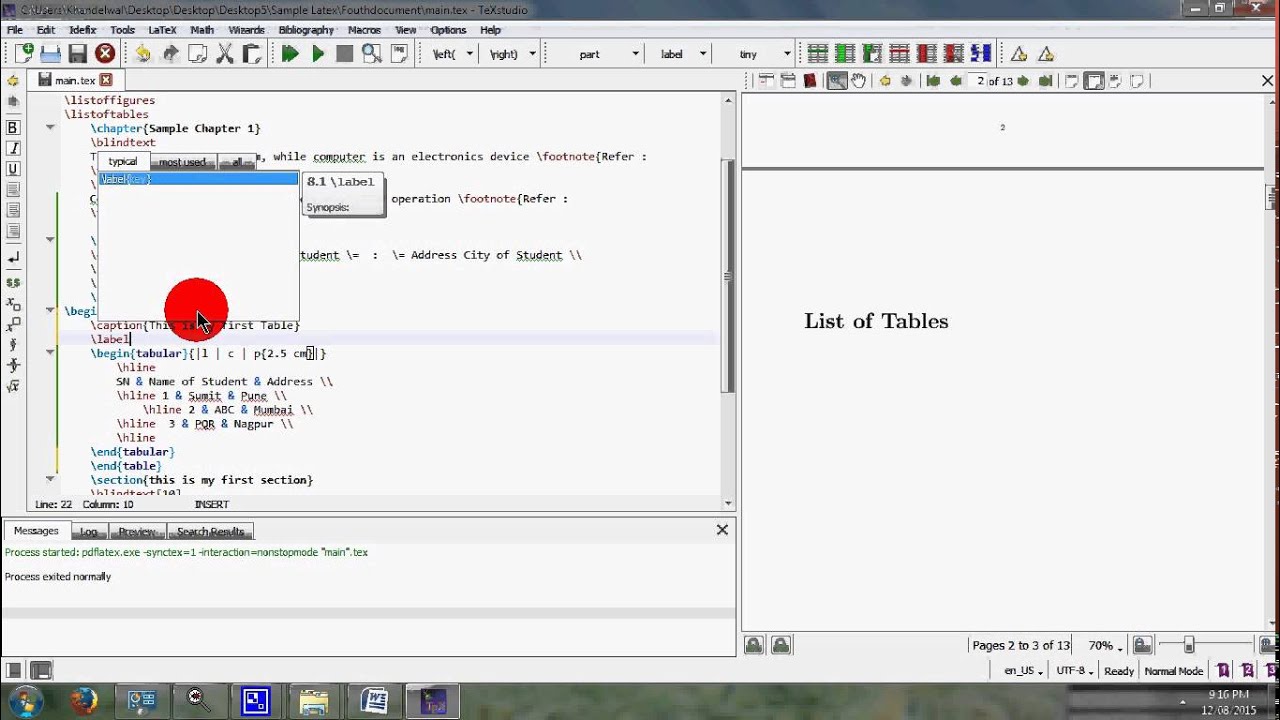

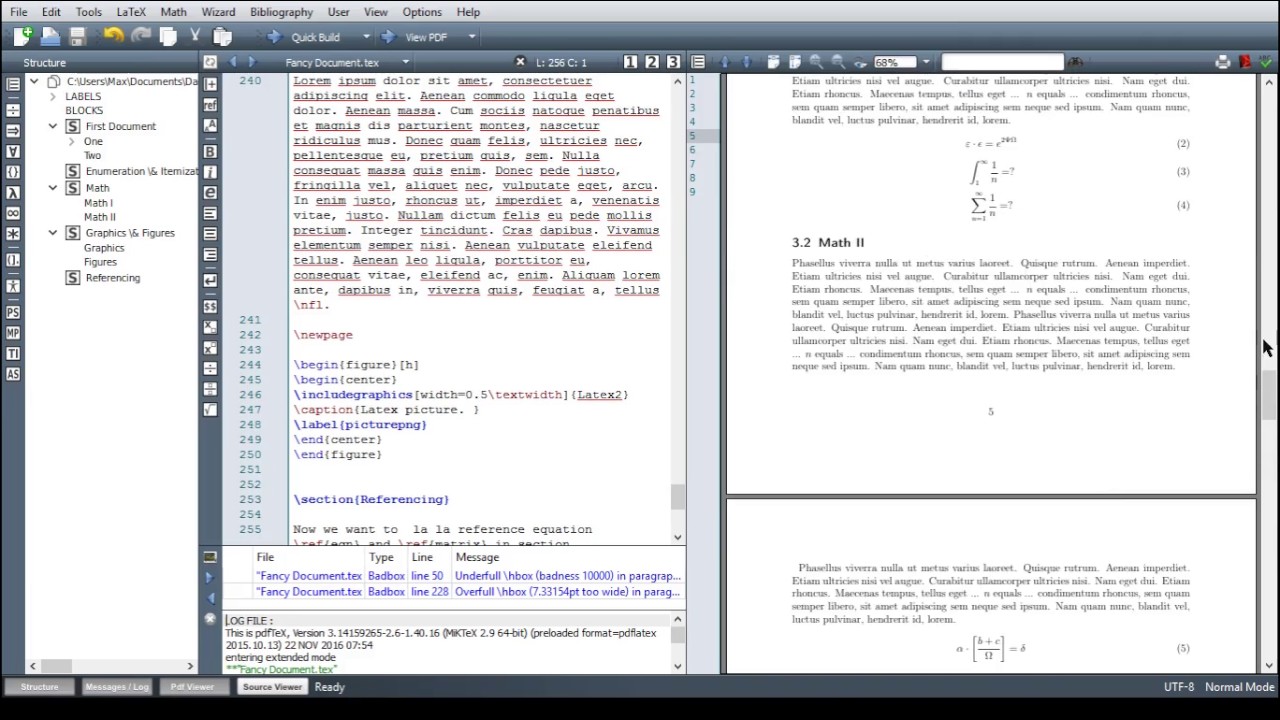

This section will give an overview the labeling capabilities of LaTeX. We will learn to label the float environments we have already covered.

Labels are a necessary part of typesetting as they are efficient pointers to information. It is better to reference Table 2 rather than "that table where I list all of those things." It is exceptionally important for equations.

One of the most useful (and occasionally underrated) properties of LaTeX is the ease and power of its labeling system. This allows one to reference equations, figures, tables, etc, with ease and flexibility. Unlike word processing software, LaTeX will automatically number and reference and change the numbering based on additions and deletions with no extra input from the writer.

There are ways to label many of the examples we have already covered. Try the following code.

We can see that we never explicitly label any of the equation, tables, figures, or subfigures. If LaTeX cannot find the proper label, you will see the ?? symbol.

When run is pressed in the environments you are most likely using (all of the ones in the installation section), LaTeX is actually compiling multiple times. There are several reasons for this, but one is due to labeling. The program first goes through the document and finds all the labels and writes them to an auxiliary file. When run again, it can properly write and link to the labels.

Since the TeX program that does the base compilation is old, it was written for computer that had very little RAM. Consequently, LaTeX stores data between runs in output files of text such as the .log and .aux files. It then reads in these files in the next run. Modern computers could easily store all of this data, but this is a case where nobody wants to change and debug something that works so well.

Try adding in more equations and changing their order, you will find that LaTeX will handle all the labeling for you.

Warning! It matters where the \label command is placed relative to the \caption command.

In this example we have also used the hyperref package. It creates a linked page where we can click on the numbers and the the pdf will automatically take us to the location in the document. For a longer document this can be very useful.

Note: the naming scheme I have used as the argument for the \label command is not necessary. However, it is a good habit since it can help keep the labels disparate among different float types and ,perhaps more importantly, organized in your own head. Furthermore, some packages require this sort of naming convention.

Created by Zachary Glassman. Contact at zach.glassman@gmail.com

See figure~ \ref { fig:test } on page~ \pageref { fig:test } .

\section { Greetings }

\label { sec:greetings }

Hello!

\section { Referencing }

I greeted in section~ \ref { sec:greetings } .

\begin { figure }

\centering

\includegraphics [width=0.5\textwidth] { gull }

\caption { Close-up of a gull }

\label { fig:gull }

\end { figure }

Figure~ \ref { fig:gull } shows a photograph of a gull.

\caption { Close-up of a gull \label { fig:gull }}

\begin { figure }

\centering

\includegraphics [width=0.5\textwidth] { gull }

\caption { Close-up of a gull } \label { fig:gull }

\end { figure }

\usepackage { caption } % hypcap is true by default so [hypcap=true] is optional in \usepackage[hypcap=true]{caption}

\begin { equation } \label { eq:solve }

x ^ 2 - 5 x + 6 = 0

\end { equation }

\begin { equation }

x _ 1 = \frac { 5 + \sqrt { 25 - 4 \times 6 }}{ 2 } = 3

\end { equation }

\begin { equation }

x _ 2 = \frac { 5 - \sqrt { 25 - 4 \times 6 }}{ 2 } = 2

\end { equation }

and so we have solved equation~ \ref { eq:solve }

\def\sectionautorefname { Section }

\section { MyFirstSection } \label { sec:marker }

\section { MySecondSection }

In section~ \nameref { sec:marker } we defined...

%The link location will be placed on the line below.

\phantomsection

\label { the _ label }

Content is available under CC BY-SA 3.0 unless otherwise noted.

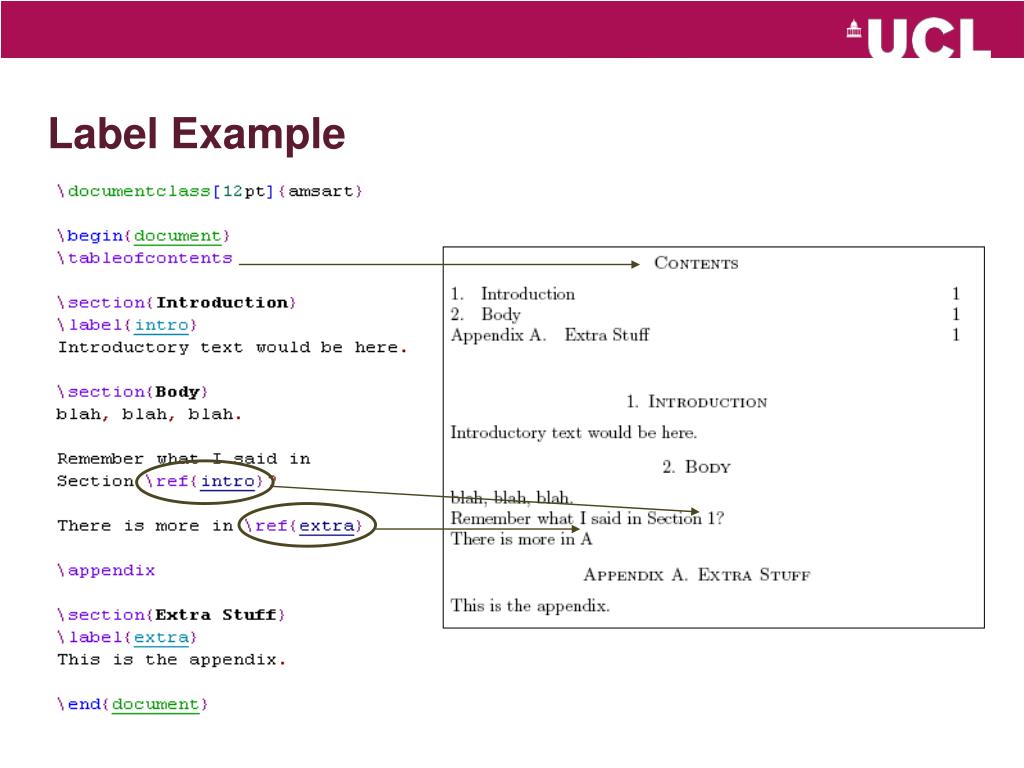

In LaTeX, you can easily reference almost anything that can be numbered, and have LaTeX automatically updating the numbering for you whenever necessary. The objects which can be referenced include chapters, sections, subsections, footnotes, theorems, equations, figures and tables [1] . The commands to be used do not depend on what you are referencing, and they are:

LaTeX will calculate the right numbering for the objects in the document; the marker you have used to label the object will not be shown anywhere in the document. Instead, LaTeX will replace the string " \ref{ marker } " with the right number that was assigned to the object. If you reference a marker that does not exist, the compilation of the document will be successful but LaTeX will return a warning:

and it will replace " \ref{ unknown-marker } " with "??" — so that it will be easier to find in the document.

As you may have noticed, this way of cross-referencing is a two-step process: first the compiler has to store the labels with the right number to be used for referencing, then it has to replace the \ref with the right number.

Because of that, you would have to compile your document twice to see the output with the proper numbering. If you only compile it once, then LaTeX will use the older information collected in previous compilations (which might be outdated), and the compiler will inform you by printing the following message at the end of the compilation:

Using the command \pageref{} you can help the reader to find the referenced object by providing also the page number where it can be found. You could write something like:

Since you can use exactly the same commands to reference almost anything, you might get a bit confused after you have introduced a lot of references. It is common practice among LaTeX users to add a few letters to the label to describe what you are referencing. Some packages, such as fancyref , rely on this meta information. Here is an example:

Following this convention, the label of a figure will look like \label{fig: my_figure } , etc. You are not obligated to use these prefixes, and can in fact use any string as an argument of \label{...} , but these prefixes can become increasingly useful as your document grows in size.

Another suggestion: try to avoid using numbers within labels. You are better off describing what the object is about. This way, if you change the order of the objects, you will not have to rename all your labels and their references.

If you want to be able to see the markers you are using in the output document as well, you can use the showkeys package; this can become very useful as you develop your document. For more information see the Packages section.

Here are some practical examples, but you will notice that they are all the same because they all use the same commands.

You could place the label anywhere in the section; however, in order to avoid confusion, it is better to place it immediately after the beginning of the section. Note how the marker starts with sec: , as suggested before. The label is then referenced in a different section, where the tilde (~) indicates a non-breaking space .

You can reference a picture by inserting it in the figure floating environment.

When a label is declared within a float environment, the \ref{...} will return the respective figure/table number, but it must occur after the caption. When declared outside, it will give the section number. To be completely safe, the label for any picture or table can go within the \caption{} command, as follows:

For more, see the Floats, Figures and Captions section about the figure and related environments.

The command \label must appear after (or inside) \caption . Otherwise, it will pick up the current section or the list number instead of what is intended.

In case you use the package hyperref to create a PDF, the link to a table or a figure will point to its caption instead, which is always below the table or the figure itself [2] . As a result, the table or the figure will not be visible if it is above the pointer, which means that some scrolling-up would be required. If you want the link to point to the top of the image, you can give the option hypcap to the caption package [3] :

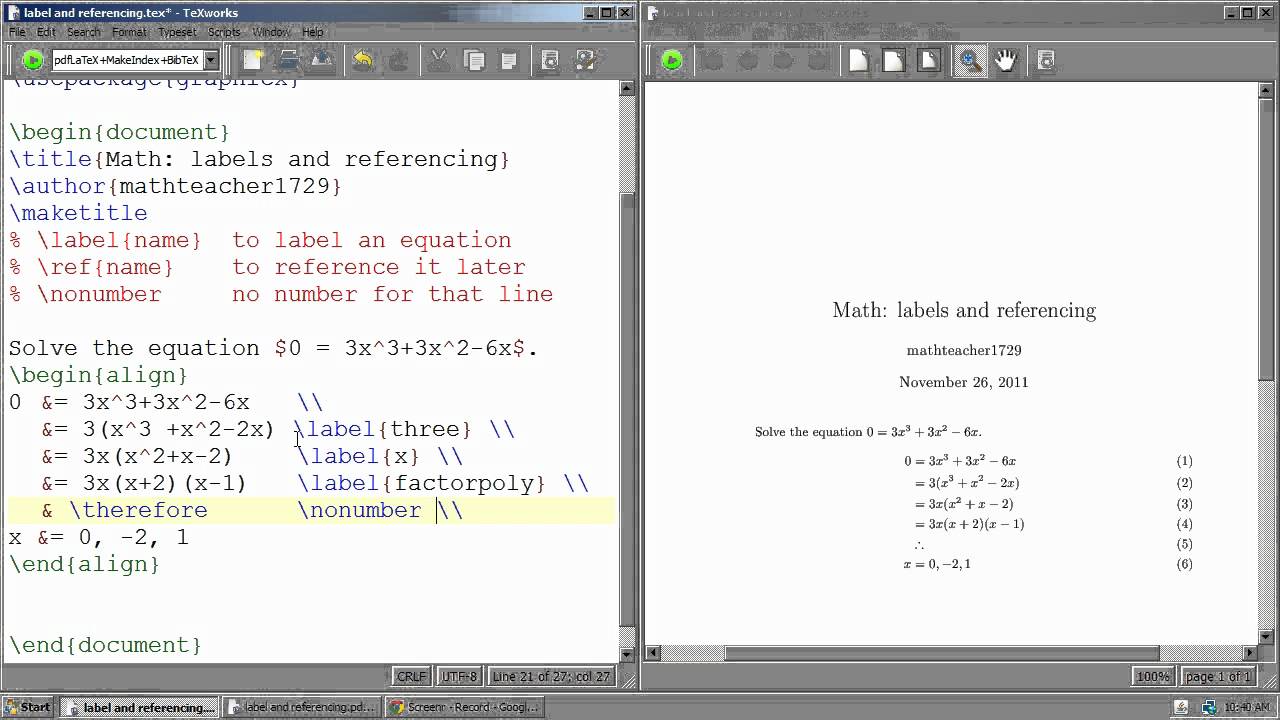

Here is an example showing how to reference formulae:

Here, notice the eq: prefix in the label — and that the label is placed soon after the beginning of the math mode. To reference a formula, an environment with counter would have to be used. Most of the times, you will be using the equation environment, as that's usually the best choice for one-line formulae whether you are using amsmath or not.

The amsmath package adds a new command for referencing formulae; it is \eqref{} . It works exactly like \ref{} , but adds parentheses so that instead of printing a plain number as 5 , it will print (5) . This can be useful to help the reader distinguish between formulae and other things, without the need to repeat the word "formula" before any reference. [4] Its output can be changed as desired; for more information see the amsmath documentation.

The \tag{ eqnno } command is used to manually set equation numbers, where eqnno is the text string you want to display instead of the usual equation number. It is normally better to use labels, but sometimes hard-coded equation numbers might offer a useful work-around — such as the case where you want to repeat an equation that has already been used before (e.g. \tag{\ref{eqn:before}} ).

The amsmath package adds the \numberwithin{countera}{counterb} command, which replaces the simple countera with a more sophisticated

counterb.countera . For example, \numberwithin{equation}{section} in the preamble will prepend the section number to all equation numbers.

The cases package adds the \numcases and the \subnumcases commands, which produce multi-case equations with a separate equation number and a separate equation number plus a letter, respectively, for each case.

The varioref package introduces a new command called \vref{} . This command is used exactly like the basic \ref , but it has a different output according to the context. If the object to be referenced is in the same page, it works just like \ref ; if the object is far away, it will print something like "5 on page 25", i.e. it adds the page number automatically. If the object is close, it can use more refined sentences such as "on the next page" or "on the facing page" automatically — according to the context and the document class.

This command has to be used very carefully. It outputs more than one word, so it may happen that its output falls on two different pages. In this case, the algorithm can get confused and cause a loop.

For example, you could label an object on page 23 and the \vref output could happen to stay between page 23 and 24. If it were on page 23, it would print like the basic ref , if it were on page 24, it would print "on the previous page", but it is on both , and this may cause some strange errors at compiling time that could be very difficult to fix.

And while for small documents, these situations might happen very rarely, for long documents spanning hundreds of references, these situations are more likely to happen. One way to avoid these problems during document preparation is to use the standard ref all the way through at first, convert all to vref when the document is close to its final version — before making the adjustment to fix any possible problem.

The hyperref package introduces another useful command; \autoref{} . This command creates a reference with additional text corresponding to the target's type, all of which will be a hyperlink. For example, the command \autoref{sec:intro} would create a hyperlink to the \label{sec:intro} command, wherever it is. Assuming that this label is pointing to a section, the hyperlink would contain the text "section 3.4", or similar (the full list of default names can be found here ). Note that, while there's an \autoref* command that produces an unlinked prefix (useful if the label is on the same page as the reference), no alternative \Autoref command is defined to produce capitalized versions (useful, for instance, when starting sentences); but since the capitalization of autoref names was chosen by the package author, you can customize the prefixed text by redefining \ type autorefname to the prefix you want, as in:

This renaming trick can, of course, be used for other purposes as well.

The hyperref package also automatically includes the nameref package, and a similarly named command. It is similar to \autoref{} , but inserts text corresponding to the section name, for example.

In section MyFirstSection we defined...

When you define a \label outside a figure, a table, or other floating objects, the label points to the current section. In some cases, this behavior is not what you'd like and you'd prefer the generated link to point to the line where the \label is defined. This can be achieved with the command

\phantomsection as in this example:

The cleveref package introduces the new command \cref{} which includes the type of referenced object like \autoref{} does. The alternate \labelcref{} command works more like standard \ref{} . References to pages are handled by the \cpageref{} command.

The \crefrange{}{} and \cpagerefrange{} commands expect a start and end label in either order and provide a natural language ( babel enabled) range. If labels are enumerated as a comma-separated list in the usual \cref{} command, it will sort them and group into ranges automatically. [5]

The format can be specified in the preamble.

Because varioref , hyperref , and cleveref redefine the same commands, they can produce unexpected results when their \usepackage commands appear in the preamble in the wrong order. For example, using hyperref , varioref , then cleveref can cause \vref{} to fail as though the marker were undefined. [6] The following order generally seems to work:

https://www1.cmc.edu/pages/faculty/aaksoy/latex/latexsix.html

https://en.m.wikibooks.org/wiki/LaTeX/Labels_and_Cross-referencing

Lesbian Japan Uncensored 2

Hentai Neko Bondage

Big Asses Creampie Big Cock

LaTeX Tutorial-Labels

LaTeX/Labels and Cross-referencing - Wikibooks, open books ...

Fancy Labels and References in LaTeX – texblog

Referencing Figures - Overleaf, Online LaTeX Editor

LaTeX 之 \label 的运用 -------图表,公式 的引用_kebu12345678 …

31 How To Label Equations In Latex - Best Labeling Ideas

Cross referencing sections, equations and floats ...

LaTeX Math Symbols

Custom Labels in enumerated List - LaTeX .org

Latex Label

%3aformat(jpeg)%3amode_rgb()%3aquality(90)/discogs-images/L-12827-1481863695-6083.jpeg.jpg)

%3aformat(jpeg)%3amode_rgb()%3aquality(90)/discogs-images/L-59865-1495741786-4549.jpeg.jpg)