Lactation Pregnant

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Navbar Search Filter

This issue

All The Journal of Nutrition

All ASN Journals

All Journals

Mobile Microsite Search Term Search

search filter

This issue

All The Journal of Nutrition

All ASN Journals

All Journals

search input Search

3Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892

2To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: PiccianM@OD.NIH.GOV.

Search for other works by this author on:

From the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conference “Dietary Supplement Use in Women: Current Status and Future Directions” held on January 28–29, 2002, in Bethesda, MD. The conference was sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Office of Dietary Supplements, NIH, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and was cosponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Food and Drug Administration Office of Women's Health, NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Division of Nutrition Research Coordination, DHHS; National Center for Complementary Medicine, U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service; International Life Sciences Institute North America; March of Dimes; and Whitehall Robbins Healthcare. Conference proceedings were published in a supplement to The Journal of Nutrition. Guest editors for this workshop were Mary Frances Picciano, Office of Dietary Supplements, NIH, DHHS; Daniel J. Raiten, Office of Prevention Research and International Programs, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS; and Paul M. Coates, Office of Dietary Supplements, NIH, DHHS.

The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 133, Issue 6, June 2003, Pages 1997S–2002S, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.6.1997S

Mary Frances Picciano, Pregnancy and Lactation: Physiological Adjustments, Nutritional Requirements and the Role of Dietary Supplements, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 133, Issue 6, June 2003, Pages 1997S–2002S, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.6.1997S

Select Format

Select format

.ris (Mendeley, Papers, Zotero)

.enw (EndNote)

.bibtex (BibTex)

.txt (Medlars, RefWorks)

Download citation

Navbar Search Filter

This issue

All The Journal of Nutrition

All ASN Journals

All Journals

Mobile Microsite Search Term Search

search filter

This issue

All The Journal of Nutrition

All ASN Journals

All Journals

search input Search

Nutritional needs are increased during pregnancy and lactation for support of fetal and infant growth and development along with alterations in maternal tissues and metabolism. Total nutrient needs are not necessarily the sum of those accumulated in maternal tissues, products of pregnancy and lactation and those attributable to the maintenance of nonreproducing women. Maternal metabolism is adjusted through the elaboration of hormones that serve as mediators, redirecting nutrients to highly specialized maternal tissues specific to reproduction (i.e., placenta and mammary gland). It is most unlikely that the heightened nutrient needs for successful reproduction can always be met from the maternal diet. Requirements for energy-yielding macronutrients increase modestly compared with several micronutrients that are unevenly distributed among foods. Altered nutrient utilization and mobilization of reserves often offset enhanced needs but sometimes nutrient deficiencies are precipitated by reproduction. There are only limited data from well-controlled intervention studies with dietary supplements and with few exceptions (iron during pregnancy and folate during the periconceptional period), the evidence is not strong that nutrient supplements confer measurable benefit. More research is needed and in future studies attention must be given to subject characteristics that may influence ability to meet maternal and infant demands (genetic and environmental), nutrient-nutrient interactions, sensitivity and selectivity of measured outcomes and proper use of proxy measures. Consideration of these factors in future studies of pregnancy and lactation are necessary to provide an understanding of the links among maternal diet; nutritional supplementation; and fetal, infant and maternal health.

The health of mothers and their infants is a priority in the United States, and Healthy People 2010, our nationwide health promotion and disease prevention agenda, identifies measurable objectives for improvement (1). Many of these objectives are based on nutrition research that offers promise for enhancing reproductive outcomes. Accumulating evidence from evaluation of public health nutrition programs and nutrient-specific intervention trials indicates that maternal nutritional modifications can and do produce desirable health advantages (2–4).

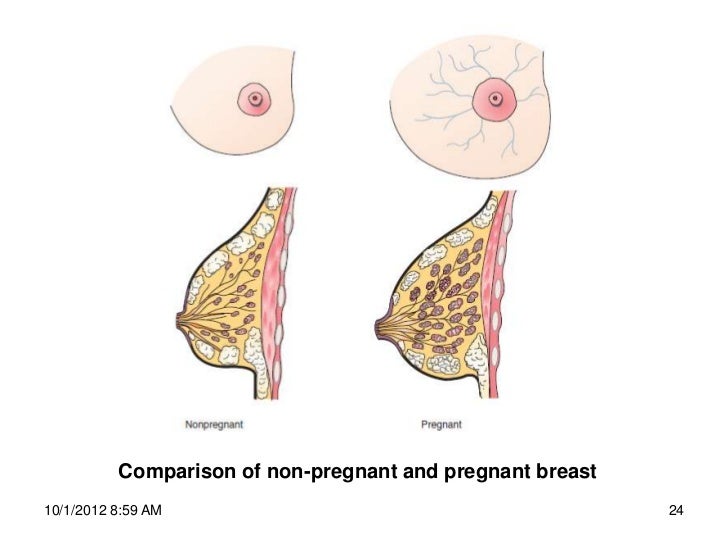

During pregnancy and lactation, nutritional requirements increase to support fetal and infant growth and development as well as maternal metabolism and tissue development specific to reproduction. Total nutrient requirements are not necessarily the simple sum of those accumulated in maternal tissues, products of pregnancy and lactation and those attributable to maintenance of nonreproducing women even though this process of summation is sometimes used to derive estimates of recommended nutrient intakes. Pregnancy and lactation are anabolic states that are orchestrated via hormones to produce a redirection of nutrients to highly specialized maternal tissues characteristic of reproduction (i.e., placenta and mammary gland) and their transfer to the developing fetus or infant. In this article the physiological adjustments and nutritional requirements of pregnant and lactating women and the possible role of dietary supplementation in meeting requirements for nutrients likely to be limiting in the diet are discussed.

Plasma levels of human chorionic gonadotropin increase immediately upon implantation of the ovum; the hormone is detectable in urine within 2 wk of implantation. It reaches a peak at ≈8 wk of gestation and then declines to a stable plateau until birth. Human chorionic gonadotropin maintains corpus luteum function for 8–10 wk. Human placental lactogen (also called human chorionic somatomammotropin) has a structure that closely resembles growth hormone, and its rate of secretion appears to parallel placental growth and may be used as a measure of placental function. At its peak, the rate of secretion of placental lactogen is 1–2 g/d, far in excess of the production of any other hormones. Placental lactogen stimulates lipolysis, antagonizes insulin actions and may be important in maintaining a flow of energy-yielding substrates to the fetus. Placental lactogen along with prolactin from the pituitary may promote mammary gland growth. After delivery, placental lactogen rapidly disappears from the circulation.

The placenta becomes the main source of steroid hormones at weeks 8–10 of gestation. Before then, progesterone and estrogens are synthesized in the maternal corpus luteum. These hormones play essential roles in maintaining the early uterine environment and development of the placenta. The placenta takes over progesterone production, which increases throughout pregnancy. Progesterone, known as the hormone of pregnancy, stimulates maternal respiration; relaxes smooth muscle, notably in the uterus and gastrointestinal tract; and may act as an immunosuppressant in the placenta, where its concentration can be 50 times greater than in plasma. Progesterone may promote lobular development in the breast and is responsible for the inhibition of milk secretion during pregnancy.

The secretion of estrogens from the placenta is complex (5). Estradiol and estrone are synthesized from the precursor dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), which is derived from both maternal and fetal blood. The synthesis of estriol is from fetal 16-α-hydroxy-dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (16-OH-DHEA-S). The fetus is unable to synthesize pregnenolone, the precursor of DHEA-S and 16-OH-DHEA-S, and must get the precursor from the placenta. The placental secretion of estrogens also increases manyfold with the progression of pregnancy. The functions of high estrogen levels in pregnancy include stimulation of uterine growth, enhancement of uterine blood flow and possibly promotion of breast development. Because estrogen precursors originate in the fetus, maternal estrogen levels can be used as a measure of fetal viability.

The increased amount of estrogens during pregnancy also stimulates a population of cells (somatotrophs) in the maternal pituitary to become mammotrophs, or prolactin-secreting cells. The increased prolactin secretion probably helps promote mammary development. In addition, the increased number of pituitary mammotrophs at the end of pregnancy provides the large amounts of prolactin necessary to initiate and maintain lactation.

During pregnancy there is an increase in blood volume of ≈35–40%, expressed as a percentage of the nonpregnant value, that results principally from the expansion of plasma volume by ≈45–50% and of red cell mass by ≈15–20% as measured in the third trimester. Because the expansion of red cell mass is proportionally less than the expansion of plasma, hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit values fall in parallel with red cell volume. Hemoglobin and hematocrit values are at their lowest in the second trimester of pregnancy and rise again in the third trimester. For these reasons, trimester-specific values for hemoglobin and hematocrit are proposed for screening for anemia in pregnant women (6).

Total plasma protein concentration falls from ≈70 to 60 g/L largely because of a fall in albumin concentration from ≈4 to 2.5 g/l00 mL near term. Plasma concentrations of α1-, α2- and β-globulins increase by ≈60%, 50% and 35%, respectively, whereas the γ-globulin fraction decreases by 13% (7). Estrogens are responsible for these changes in plasma proteins, which can be reproduced by administration of estradiol to nonpregnant women. Plasma levels of most lipid fractions, including triacylglycerol, VLDL, LDL and HDL, increase during pregnancy.

The average weight gained by healthy primigravidae eating without restriction is 12.5 kg (27.5 lb) (5). This weight gain represents two major components: 1) the products of conception: fetus, amniotic fluid and the placenta and 2) maternal accretion of tissues: expansion of blood and extracellular fluid, enlargement of uterus and mammary glands and maternal stores (adipose tissue).

Low weight gain is associated with increased risk of intrauterine growth retardation and perinatal mortality. High weight gain is associated with high birth weight and secondarily with increased risk of complications related to fetopelvic disproportion. A large body of epidemiologic evidence now shows convincingly that maternal prepregnancy weight-for-height is a determinant of fetal growth above and beyond gestational weight gain. At the same gestational weight gain, thin women give birth to infants smaller than those born to heavier women. Because higher birth weights present lower risk for infants, current recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy are higher for thin women than for women of normal weight and lower for short overweight and obese women (7). These recommendations are summarized below (Table 1).

Current recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy*

Data from Institute of Medicine (7). BMI, body mass index.

Current recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy*

Data from Institute of Medicine (7). BMI, body mass index.

Recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy were formulated in recognition of the need to balance the benefits of increased fetal growth against the risks of labor and delivery complications and of postpartum maternal weight retention. The target range for desirable weight gain in each prepregnancy weight-for-height category is that associated with delivery of a full-term infant weighing between 3 and 4 kg. Recent evidence indicates that <50% of 622 women sampled in upstate New York gained weight within the ranges recommended and that weight gain greater than these recommended amounts placed them at risk for major weight gain 1 y postdelivery (8).

Determination of nutrient needs during pregnancy is complicated because nutrient levels in tissues and fluids available for evaluation and interpretation are normally altered by hormone-induced changes in metabolism, shifts in plasma volume and changes in renal function and patterns of urinary excretion. Nutrient concentrations in blood and plasma are often decreased because of expanding plasma volume, although total circulating quantities can be greatly increased. Individual profiles vary widely, but in general, water-soluble nutrients and metabolites are present in lower concentrations in pregnant than in nonpregnant women whereas fat-soluble nutrients and metabolites are present in similar or higher concentrations. Homeostatic control mechanisms are not well understood and abnormal alterations are ill-defined.

Dietary Reference Intakes for pregnant and lactating women in comparison with those of adult, nonreproducing women are presented in Table 2. Also presented in Table 2 are comparative cumulative energy and nutrient expenditures of adult, pregnant and lactating women. The recommended intakes for pregnant adolescents generally would be increased by an amount proportional to the incomplete maternal growth at conception. The percentage increase in estimated energy requirement is small relative to the estimated increased need for most other nutrients. Accordingly, pregnant women must select foods with enhanced nutrient density or risk nutritional inadequacy.

Comparison of recommended daily energy and nutrient intakes and cumulative expenditures of adult, pregnant and lactating women

↑340 kcal/d 2nd trimester ↑452 kcal/d 3rd trimester

↑500 kcal/d 0–6 mo ↑400 kcal/d 7–9 mo

↑340 kcal/d 2nd trimester ↑452 kcal/d 3rd trimester

↑500 kcal/d 0–6 mo ↑400 kcal/d 7–9 mo

Values are from the Institute of Medicine (9–13).

Calculations are based on recommended intakes per day, assuming 9 months is equivalent to 270. Abbreviations NE, niacin equivalents; DFE, dietary folate equivalents; RE, retinol equivalents; TE, tocopherol equivalents.

and 4 are, respectively, Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA), the average daily dietary intake level that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97 to 98 percent) individuals in a life stage and gender group and based on the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR); and Adequate Intake (AI), the value used instead of an RDA if sufficient scientific evidence is not available to calculate an EAR.

Comparison of recommended daily energy and nutrient intakes and cumulative expenditures of adult, pregnant and lactating women

↑340 kcal/d 2nd trimester ↑452 kcal/d 3rd trimester

↑500 kcal/d 0–6 mo ↑400 kcal/d 7–9 mo

↑340 kcal/d 2nd trimester ↑452 kcal/d 3rd trimester

↑500 kcal/d 0–6 mo ↑400 kcal/d 7–9 mo

Values are from the Institute of Medicine (9–13).

Calculations are based on recommended intakes per day, assuming 9 months is equivalent to 270. Abbreviations NE, niacin equivalents; DFE, dietary folate equivalents; RE, retinol equivalents; TE, tocopherol equivalents.

and 4 are, respectively, Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA), the average daily dietary intake level that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97 to 98 percent) individuals in a life stage and gender group and based on the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR); and Adequate Intake (AI), the value used instead of an RDA if sufficient scientific evidence is not available to calculate an EAR.

Energy needs during pregnancy are currently estimated to be the sum of total energy expenditure of a nonpregnant woman plus the median change in total energy expenditure of 8 kcal/gestational week plus the energy deposition during pregnancy of 180 kcal/d (13). Because total energy expenditure does not change greatly and weight gain is minimal in the first trimester, additional energy intake is recommended only in the second and third trimesters. Approximately an additional 340 and 450 kcal are recommended during the second and third trimesters, respectively.

Additional protein is needed during pregnancy to cover the estimated 21 g/d deposited in fetal, placental and maternal tissues during the second and third trimesters (13). Women of reproductive age select diets containing average protein intakes of ≈70 g/d (14), a value very close to the theoretical need of 71 g during pregnancy.

The assessment of vitamin and mineral status during pregnancy is difficult because there is a general lack of pregnancy-specific laboratory indexes for nutritional evaluation. Plasma concentrations of many vitamins and minerals show a slow, steady decrease with the advance of gestation, which may be due to hemodilution; however, other vitamins and minerals can be unaffected or increased because of pregnancy-induced changes in levels of carrier molecules (15). When these patterns are unaltered by elevated maternal intakes, it is easy to conclude that they represent a normal physiological adjustment to pregnancy rather than increased needs or deficient intakes. Even when enhanced maternal intake does induce a change in an observed pattern, interpretation of such a change is difficult unless it can be related to some functional consequence (15). For these reasons, much of our knowledge is based on observational studies and intervention trials in which low or high maternal intakes are associated with adverse or favorable pregnancy outcomes. Available data on vitamin and mineral metabolism and requirements during pregnancy are fragmentary at best, and it is exceedingly difficult to determine consequences of seemingly deficient or excessive intakes in human populations. However, animal data show convincingly that maternal vitamin and mineral deficiencies can cause fetal growth retardation and congenital anomalies. Similar associations in humans are rare. Selected vitamins and minerals that are likely to be limiting or excessive in the diets of pregnant women and their association with pregnancy outcome are briefly discussed.

Placental transport of vitamin A between mother and fetus is substantial, and recommended intakes are increased by ≈10% (12). Low maternal vitamin A status is inconsistently associated with intrauterine growth retardation in communities at risk for vitamin A deficiency. Dietary supplementation with vitamin A or β-carotene is reported to reduce maternal mortality by 40% but to not affect fetal loss or infant mortality rates (16,17). Overt vitamin A deficiency is not apparent in the United States; instead, the concern during pregnancy is about excess (18).

The main circulating form of vitamin D in plasma, 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, is responsive to increased maternal intake and falls w

Old Grandpa Mobile Sex Movies

Watch Long Porn Videos For Free Small

Black Old Porno

Full Sex Old Semana

Massage Pregnant

Lactation During Pregnancy - Lactation Questions

Pregnancy and Lactation: Physiological Adjustments ...

Pregnancy and lactation alter biomarkers of biotin ...

Biologicals in pregnancy and lactation

Nutrient Requirements during Pregnancy and Lactation

Lactating but not pregnant: Causes and symptoms

Vaccinating Pregnant and Lactating Patients Against COVID ...

Lactation Pregnant

.jpg)