James Baldwin Writings

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Tony Barnstone

Kyle Dargan

Jack Collom

Nikky Finney

Craig Dworkin

Pat Mora

Alistair Campbell

Bob Dylan

Gregory Pardlo

Erika T. Wurth

Tony Barnstone

Kyle Dargan

Jack Collom

Nikky Finney

Craig Dworkin

Pat Mora

Alistair Campbell

Bob Dylan

Gregory Pardlo

Erika T. Wurth

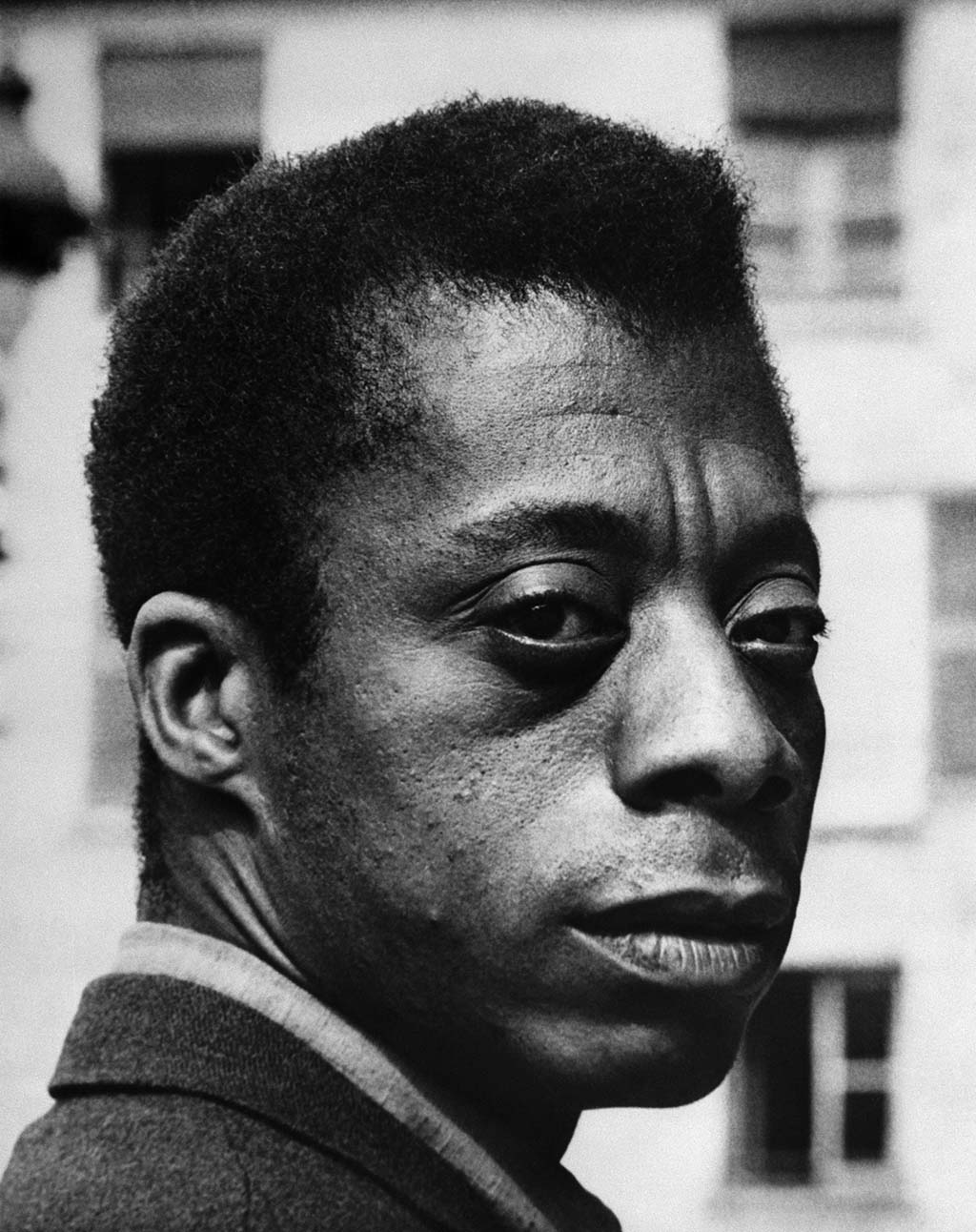

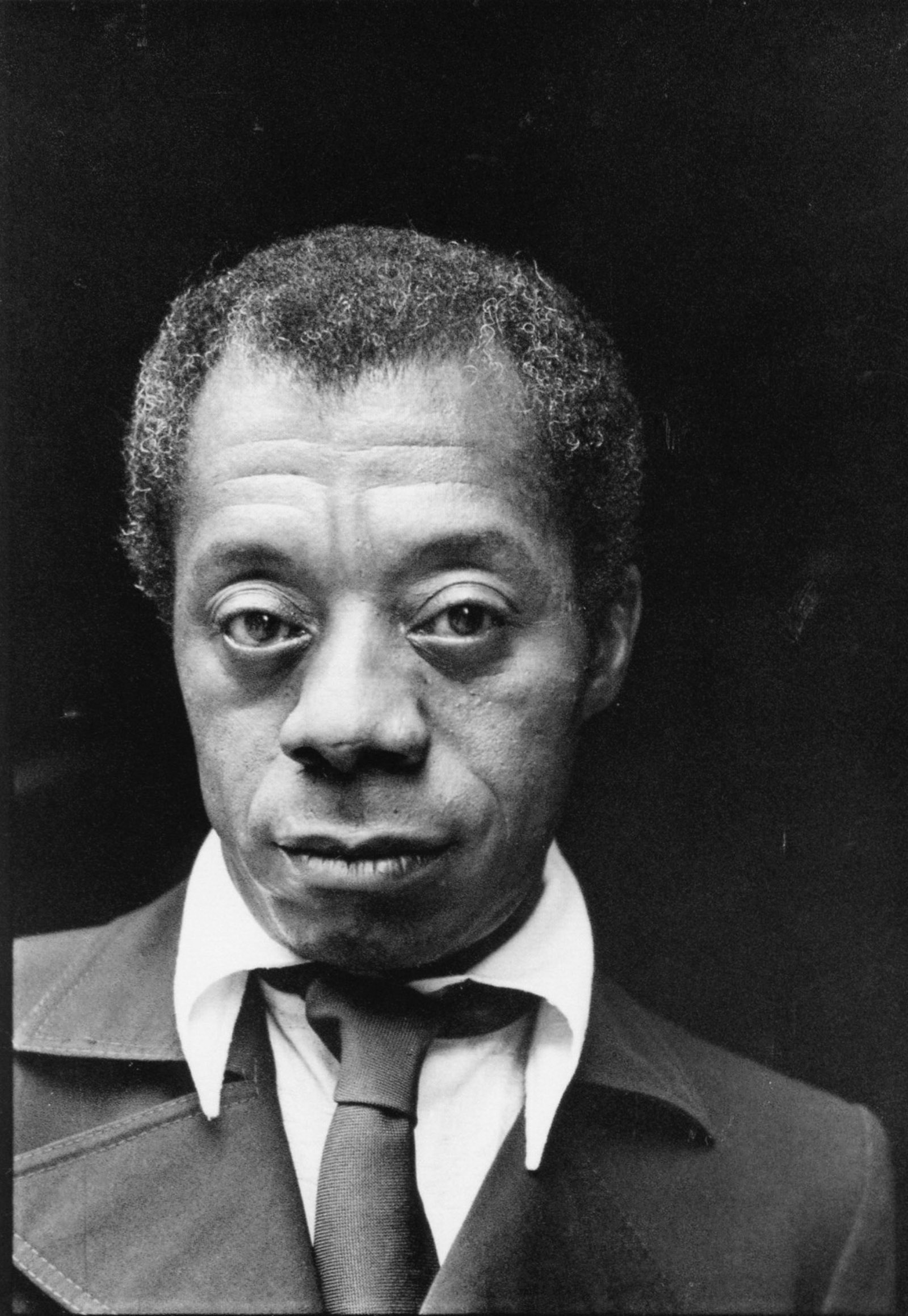

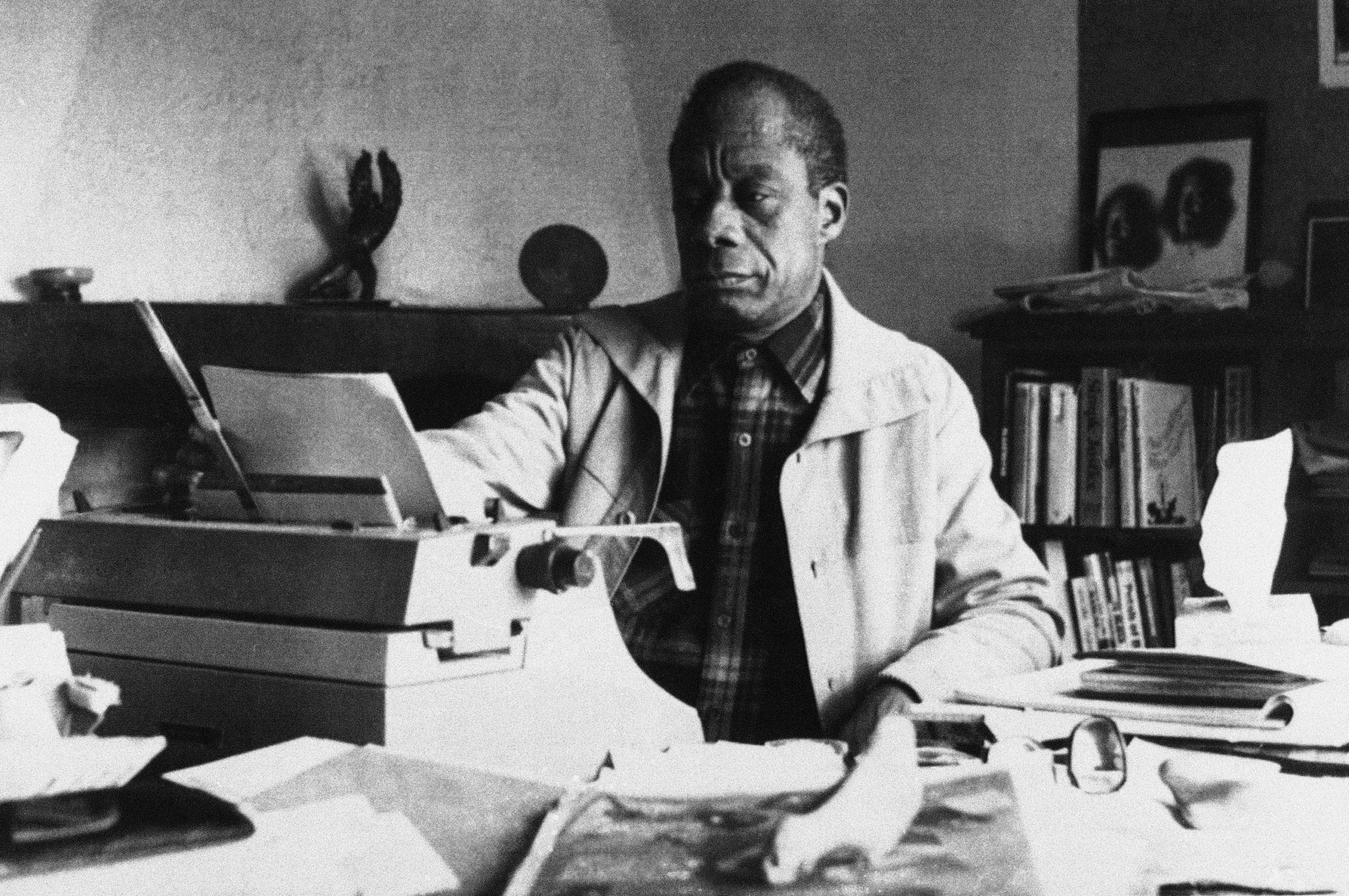

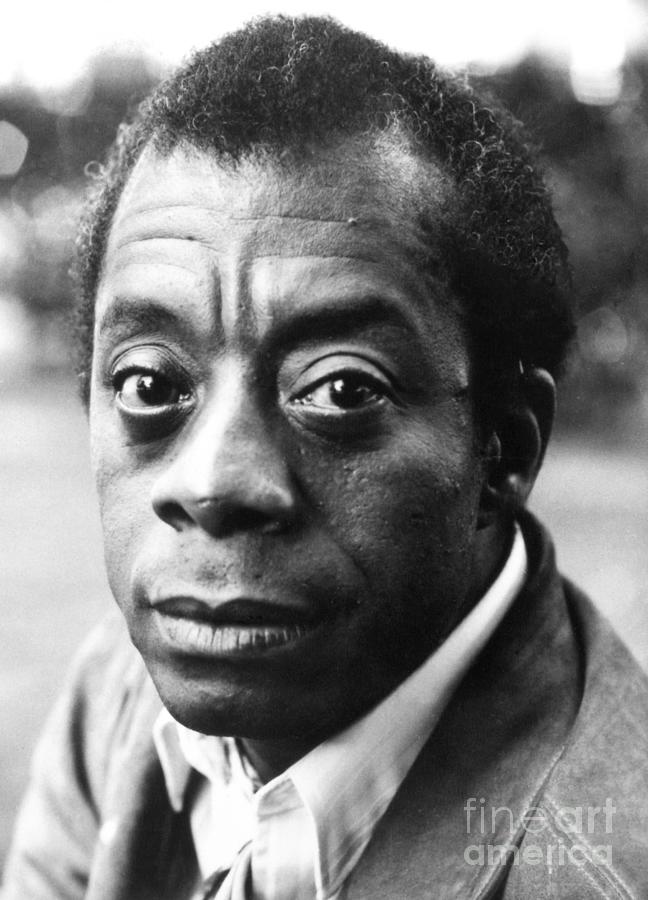

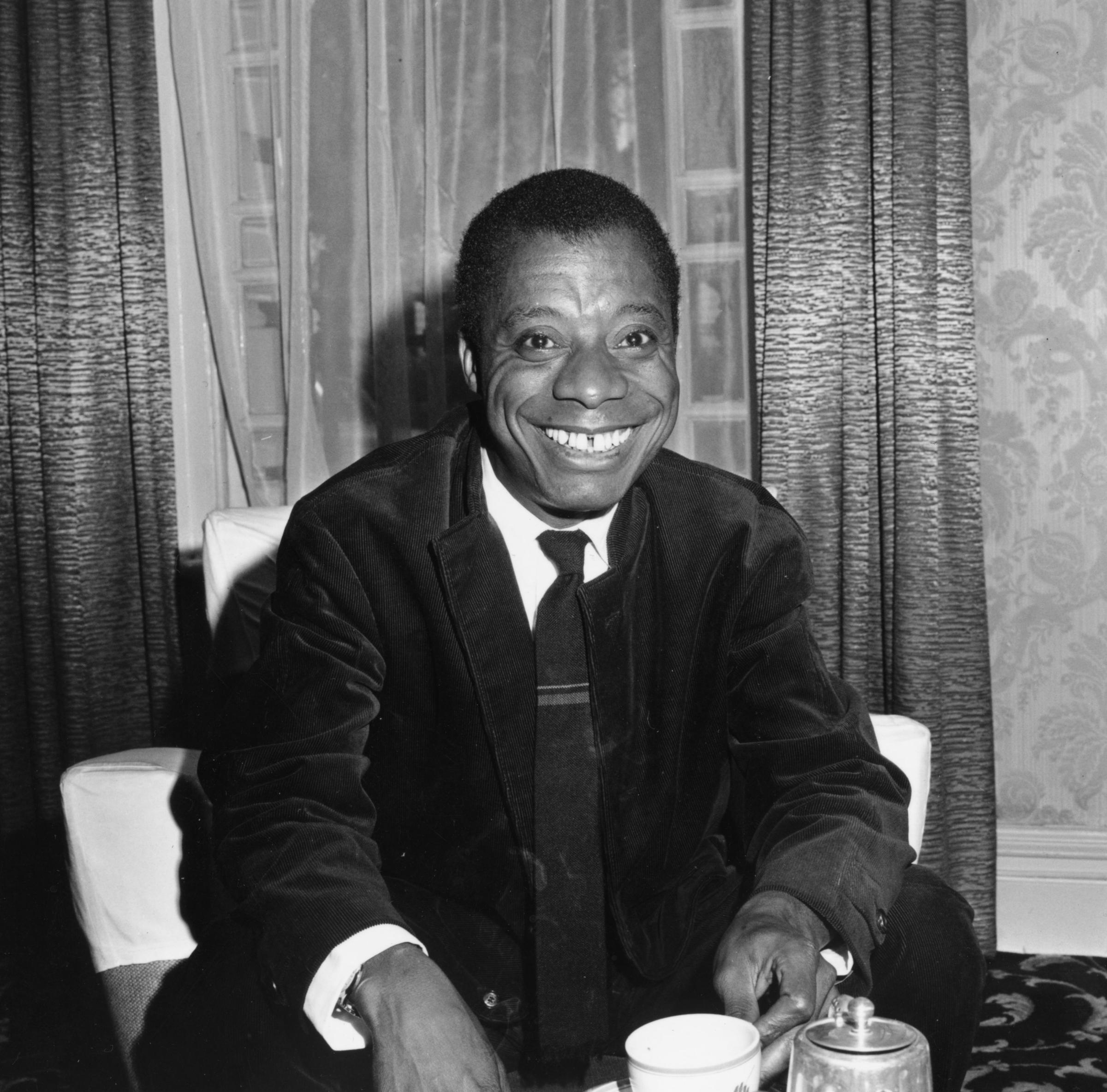

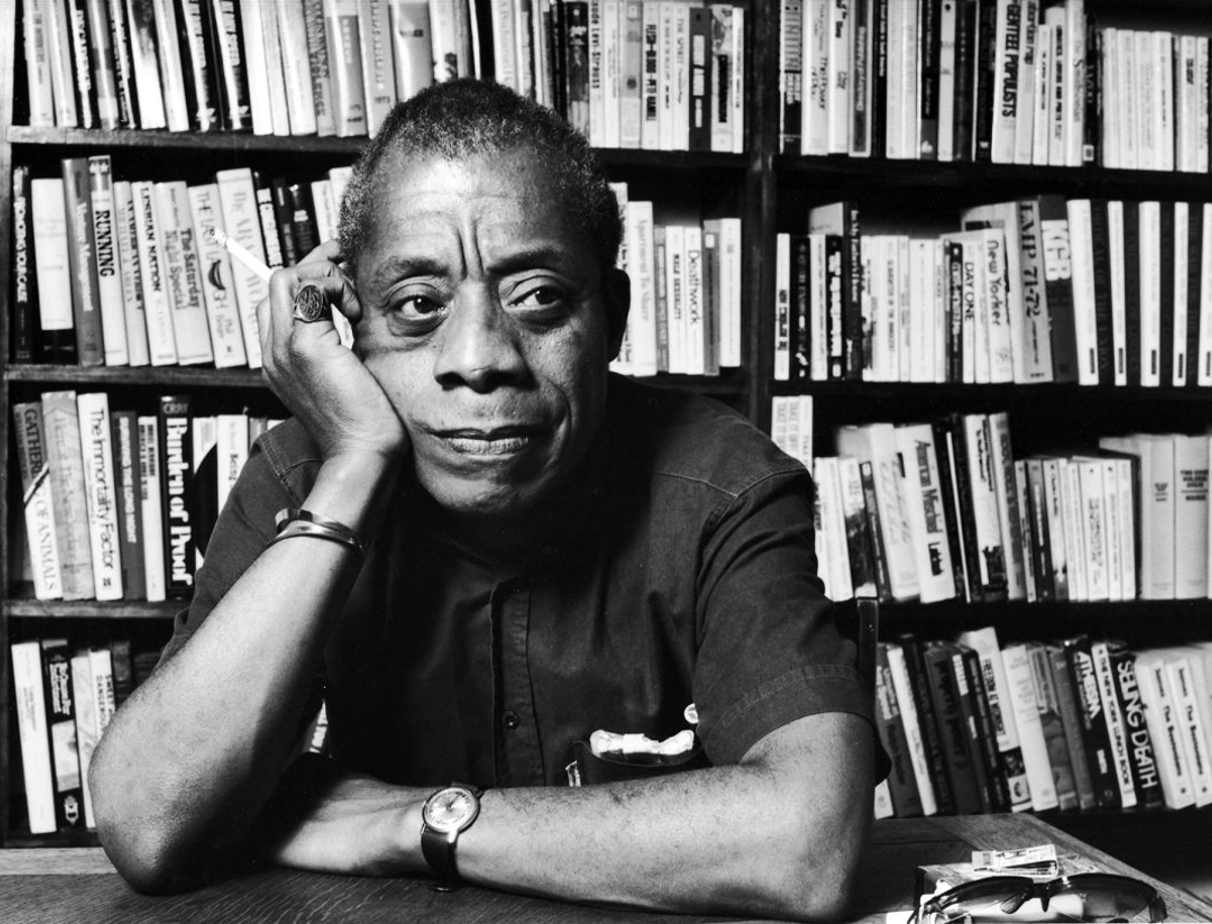

James Baldwin, 1964. Photo by Jean-Regis Rouston/Roger Viollet/Getty Images.

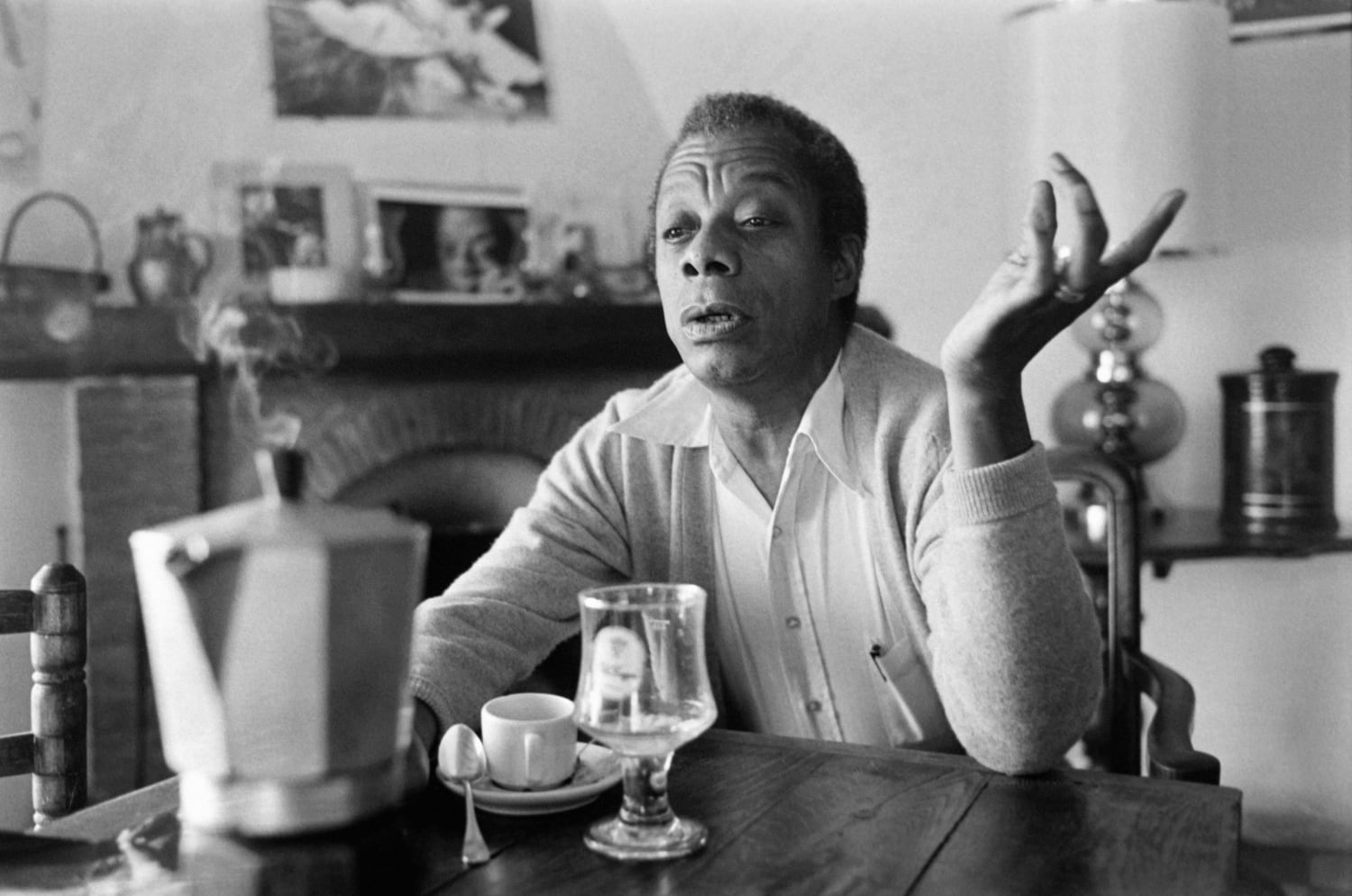

A novelist and essayist of considerable renown, James Baldwin bore witness to the unhappy consequences of American racial strife. Baldwin’s writing career began in the last years of legislated segregation; his fame as a social observer grew in tandem with the civil rights movement as he mirrored blacks’ aspirations, disappointments, and coping strategies in a hostile society. Tri-Quarterly contributor Robert A. Bone declared that Baldwin’s publications “have had a stunning impact on our cultural life” because the author “... succeeded in transposing the entire discussion of American race relations to the interior plane; it is a major breakthrough for the American imagination.” In his novels, plays, and essays alike, Baldwin explored the psychological implications of racism for both the oppressed and the oppressor. Best-sellers such as Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son and The Fire Next Time acquainted wide audiences with his highly personal observations and his sense of urgency in the face of rising black bitterness. As Juan Williams noted in the Washington Post, long before Baldwin’s death, his writings “became a standard of literary realism. ... Given the messy nature of racial hatred, of the half-truths, blasphemies and lies that make up American life, Baldwin’s accuracy in reproducing that world stands as a remarkable achievement. ... Black people reading Baldwin knew he wrote the truth. White people reading Baldwin sensed his truth about the lives of black people and the sins of a racist nation.”

Critics accorded Baldwin high praise for both his style and his themes. “Baldwin has carved a literary niche through his exploration of ‘the mystery of the human being’ in his art,” observed Louis H. Pratt in James Baldwin. “His short stories, novels, and plays shed the light of reality upon the darkness of our illusions, while the essays bring a boldness, courage, and cool logic to bear on the most crucial questions of humanity with which this country has yet to be faced.” In the College Language Association Journal, Therman B. O’Daniel called Baldwin “the gifted professor of that primary element, genuine talent. ... Secondly he is a very intelligent and deeply perceptive observer of our multifarious contemporary society. ... In the third place, Baldwin is a bold and courageous writer who is not afraid to search into the dark corners of our social consciences, and to force out into public view many of the hidden, sordid skeletons of our society. ... Then, of course, there is Baldwin’s literary style which is a fourth major reason for his success as a writer. His prose ... possesses a crystal clearness and a passionately poetic rhythm that makes it most appealing.” Saturday Review correspondent Benjamin De Mott concluded that Baldwin “retains a place in an extremely select group: That composed of the few genuinely indispensable American writers. He owes his rank partly to the qualities of responsiveness that have marked his work from the beginning. ... Time and time over in fiction as in reportage, Baldwin tears himself free of his rhetorical fastenings and stands forth on the page utterly absorbed in the reality of the person before him, strung with his nerves, riveted to his feelings, breathing his breath.”

Baldwin’s central preoccupation as a writer lay in “his insistence on removing, layer by layer, the hardened skin with which Americans shield themselves from their country,” according to Orde Coombs in the New York Times Book Review. The author saw himself as a “disturber of the peace”—one who revealed uncomfortable truths to a society mired in complacency. Pratt found Baldwin “engaged in a perpetual battle to overrule our objections and continue his probe into the very depths of our past. His constant concern is the catastrophic failure of the American Dream and the devastating inability of the American people to deal with that calamity.” Pratt uncovered a further assumption in Baldwin’s work; namely, that all of mankind is united by virtue of common humanity. “Consequently,” Pratt stated, “the ultimate purpose of the writer, from Baldwin’s perspective, is to discover that sphere of commonality where, although differences exist, those dissimilarities are stripped of their power to block communication and stifle human intercourse.” The major impediment in this search for commonality, according to Baldwin, is white society’s entrenched moral cowardice, a condition that through longstanding tradition equates blackness with dark impulses, carnality and chaos. By denying blacks’ essential humanity so simplistically, the author argued, whites inflict psychic damage on blacks and suffer self-estrangement—a “fatal bewilderment,” to quote Bone. Baldwin’s essays exposed the dangerous implications of this destructive way of thinking; his fictional characters occasionally achieve interracial harmony after having made the bold leap of understanding he advocated. In the British Journal of Sociology, Beau Fly Jones claimed that Baldwin was one of the first black writers “to discuss with such insight the psychological handicaps that most Negroes must face; and to realize the complexities of Negro-white relations in so many different contexts. In redefining what has been called the Negro problem as white, he has forced the majority race to look at the damage it has done, and its own role in that destruction.”

Essayist John W. Roberts felt that Baldwin’s “evolution as a writer of the first order constitutes a narrative as dramatic and compelling as his best story.” Baldwin was born and raised in Harlem under very trying circumstances. His stepfather, an evangelical preacher, struggled to support a large family and demanded the most rigorous religious behavior from his nine children. Roberts wrote: “Baldwin’s ambivalent relationship with his stepfather served as a constant source of tension during his formative years and informs some of his best mature writings. ... The demands of caring for younger siblings and his stepfather’s religious convictions in large part shielded the boy from the harsh realities of Harlem street life during the 1930s.” As a youth Baldwin read constantly and even tried writing; he was an excellent student who sought escape from his environment through literature, movies, and theatre. During the summer of his 14th birthday he underwent a dramatic religious conversion, partly in response to his nascent sexuality and partly as a further buffer against the ever-present temptations of drugs and crime. He served as a junior minister for three years at the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly, but gradually he lost his desire to preach as he began to question blacks’ acceptance of Christian tenets that had, in essence, been used to enslave them.

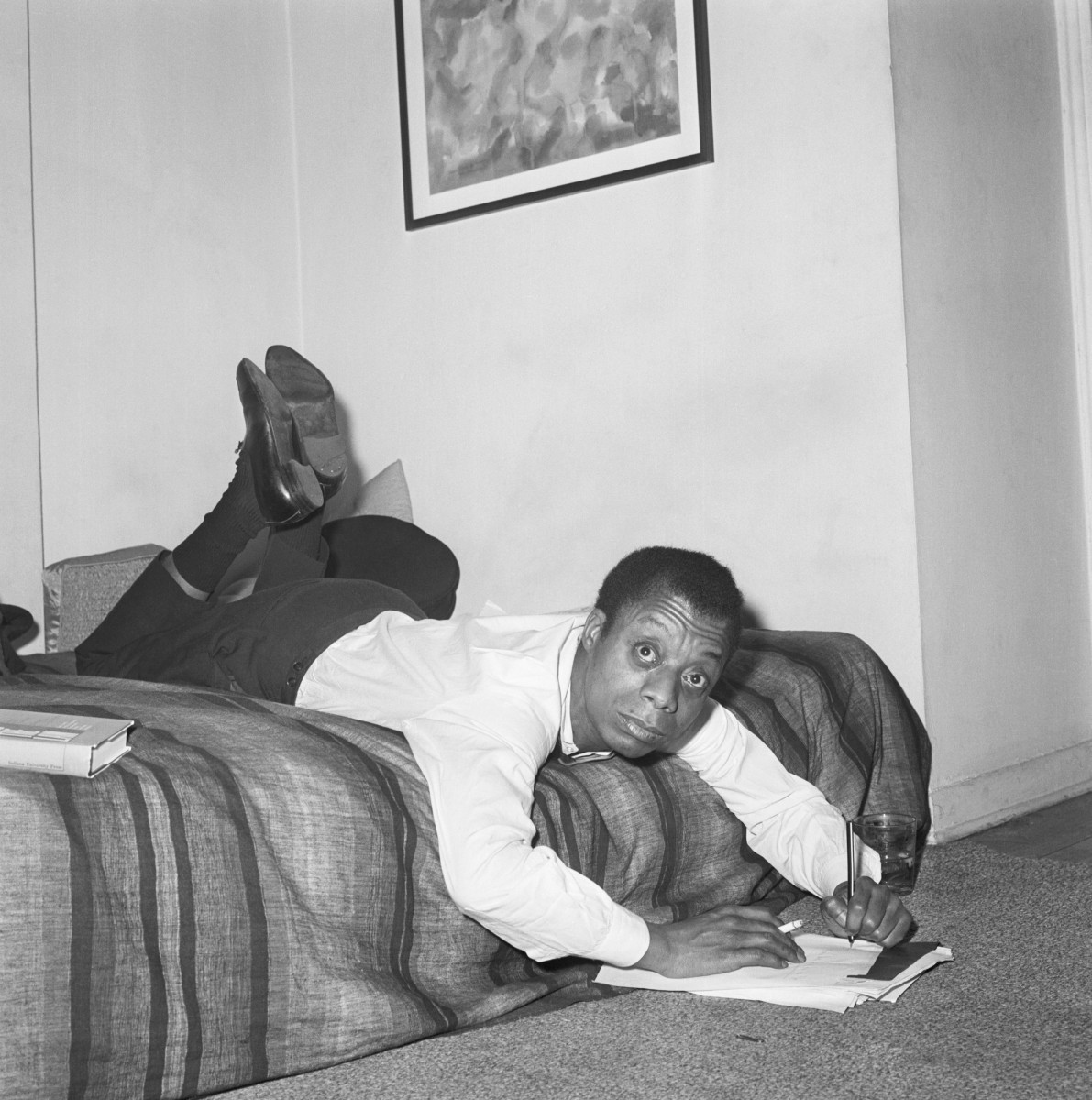

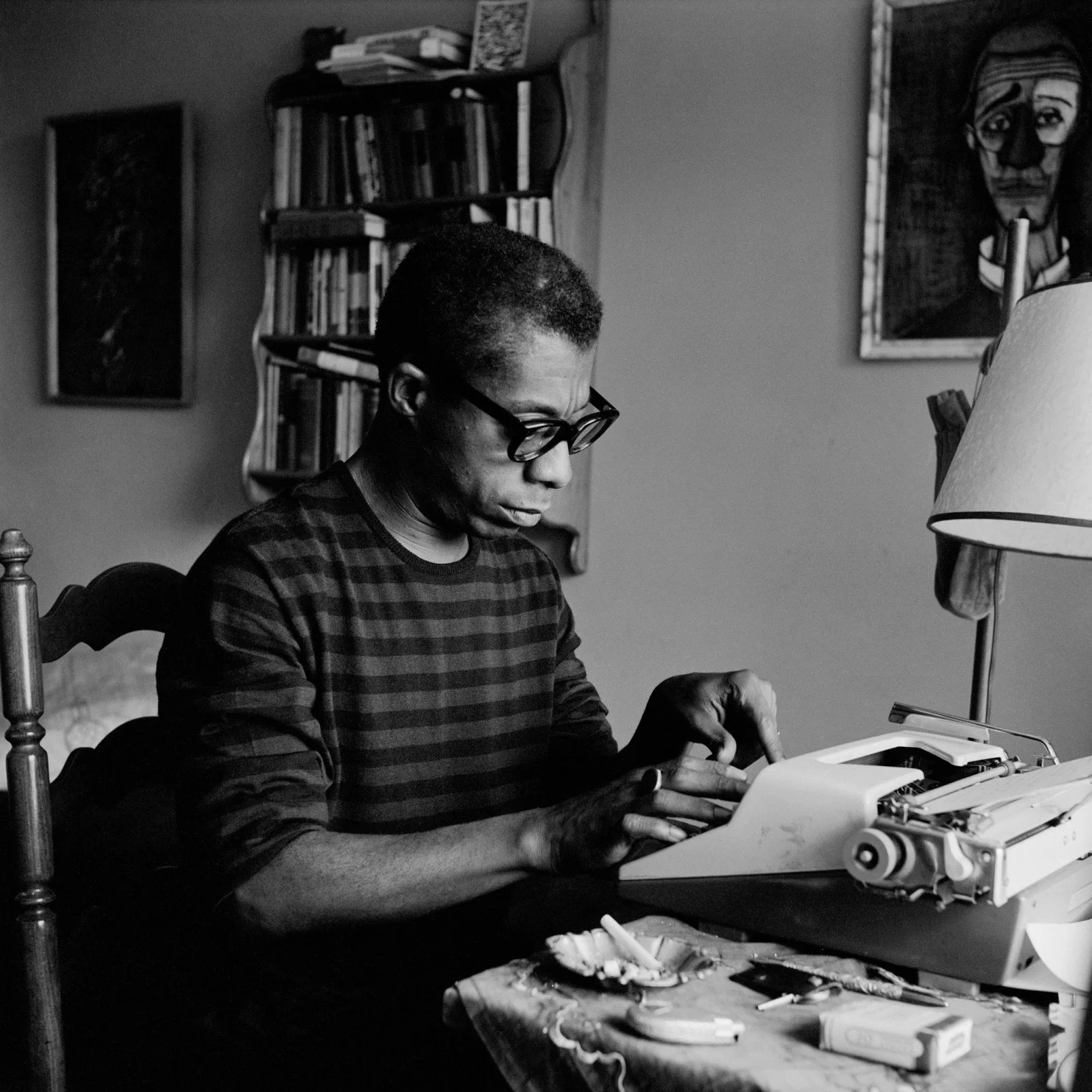

Shortly after he graduated from high school in 1942, Baldwin was compelled to find work in order to help support his brothers and sisters; mental instability had incapacitated his stepfather. Baldwin took a job in the defense industry in Belle Meade, New Jersey, and there, not for the first time, he was confronted with racism, discrimination, and the debilitating regulations of segregation. The experiences in New Jersey were closely followed by his stepfather’s death, after which Baldwin determined to make writing his sole profession. He moved to Greenwich Village and began to write a novel, supporting himself by performing a variety of odd jobs. In 1944 he met author Richard Wright, who helped him to land the 1945 Eugene F. Saxton fellowship. Despite the financial freedom the fellowship provided, Baldwin was unable to complete his novel that year. He found the social tenor of the United States increasingly stifling even though such prestigious periodicals as the Nation, New Leader, and Commentary began to accept his essays and short stories for publication. Eventually, in 1948, he moved to Paris, using funds from a Rosenwald Foundation fellowship to pay his passage. Most critics feel that this journey abroad was fundamental to Baldwin’s development as an author.

“Once I found myself on the other side of the ocean,” Baldwin told the New York Times, “I could see where I came from very clearly, and I could see that I carried myself, which is my home, with me. You can never escape that. I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with both.” Through some difficult financial and emotional periods, Baldwin undertook a process of self-realization that included both an acceptance of his heritage and an admittance of his bisexuality. Bone noted that Europe gave the young author many things: “It gave him a world perspective from which to approach the question of his own identity. It gave him a tender love affair which would dominate the pages of his later fiction. But above all, Europe gave him back himself. The immediate fruit of self-recovery was a great creative outburst. First came two [works] of reconciliation with his racial heritage. Go Tell It on the Mountain and The Amen Corner represent a search for roots, a surrender to tradition, an acceptance of the Negro past. Then came a series of essays which probe, deeper than anyone has dared, the psychic history of this nation. They are a moving record of a man’s struggle to define the forces that have shaped him, in order that he may accept himself.”

Many critics view Baldwin’s essays as his most significant contribution to American literature. Works such as Notes of a Native Son, Nobody Knows My Name, The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, and The Evidence of Things Not Seen “serve to illuminate the condition of the black man in twentieth-century America,” according to Pratt. Highly personal and analytical, the essays probe deeper than the mere provincial problems of white versus black to uncover the essential issues of self-determination, identity, and reality. “An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian,” Baldwin told Life magazine. “His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are. He has to tell, because nobody else can tell, what it is like to be alive.” South Atlantic Quarterly contributor Fred L. Standley asserted that this quest for personal identity “is indispensable in Baldwin’s opinion and the failure to experience such is indicative of a fatal weakness in human life.” C.W.E. Bigsby elaborated in The Fifties: Fiction, Poetry, Drama: “Baldwin’s central theme is the need to accept reality as a necessary foundation for individual identity and thus a logical prerequisite for the kind of saving love in which he places his whole faith. For some this reality is one’s racial or sexual nature, for others it is the ineluctable fact of death. ... Baldwin sees this simple progression as an urgent formula not only for the redemption of individual men but for the survival of mankind. In this at least black and white are as one and the Negro’s much-vaunted search for identity can be seen as part and parcel of the American’s long-standing need for self-definition.”

Inevitably, however, Baldwin’s assessments of the “sweet” and “bitter” experiences in his own life led him to describe “the exact place where private chaos and social outrage meet,” according to Alfred Kazin in Contemporaries. Eugenia Collier described this confrontation in Black World: “On all levels personal and political ... life is a wild chaos of paradox, hidden meanings, and dilemmas. This chaos arises from man’s inability—or reluctance to face the truth about his own nature. As a result of this self-imposed blindness, men erect an elaborate facade of myth, tradition, and ritual behind which crouch, invisible, their true selves. It is this blindness on the part of Euro-Americans which has created and perpetuated the vicious racism which threatens to destroy this nation.” In his essays on the 1950s and early 1960s, Baldwin sought to explain black experiences to a white readership as he warned whites about the potential destruction their psychic blindness might wreak. Massachusetts Review contributor David Levin noted that the author came to represent “for ‘white’ Americans, the eloquent, indignant prophet of an oppressed people, a voice speaking ... in an all but desperate, final effort to bring us out of what he calls our innocence before it is (if it is not already) too late. This voice calls us to our immediate duty for the sake of our own humanity as well as our own safety. It demands that we stop regarding the Negro as an abstraction, an invisible man; that we begin to recognize each Negro in his ‘full weight and complexity’ as a human being; that we face the horrible reality of our past and present treatment of Negroes—a reality we do not know and do not want to know.” In Ebony magazine, Allan Morrison observed that Baldwin evinced an awareness “that the audience for most of his nonfictional writings is white and he uses every forum at his disposal to drive home the basic truths of Negro-white relations in America as he sees them. His function here is to interpret whites to themselves and at the same time voice the Negro’s protest against his role in a Jim Crow society.”

Because Baldwin sought to inform and confront whites, and because his fiction contains interracial love affairs—both homosexual and heterosexual—he came under attack from the writers of the Black Arts Movement, who called for a literature exclusively by and for blacks. Baldwin refused to align himself with the movement; he continued to call himself an “American writer” as opposed to a “black writer” and continued to confront the issues facing a multi-racial society. Eldridge Cleaver, in his book Soul on Ice, accused Baldwin of a hatred of blacks and “a shameful, fanatical fawning” love of whites. What Cleaver saw as complicity with whites, Baldwin saw rather as an attempt to alter the real daily environment with which American blacks have been faced all their lives. Pratt noted, however, that Baldwin’s efforts to “shake up” his white readers put him “at odds with current white literary trends” as well as with the Black Arts Movement. Pratt explained that Baldwin labored under the belief “that mainstream art is directed toward a complacent and apathetic audience, and it is designed to confirm and reinforce that sense of well-being. ... Baldwin’s writings are, by their very nature, iconoclastic. While Black Arts focuses on a black-oriented artistry, Baldwin is concerned with the destruction of the fantasies and delusions of a contented audience which is determined to avoid reality.” As the civil rights movement gained momentum, Baldwin escalated his attacks on white complacency from the speaking platform as well as from the pages of books and magazines. Nobody Knows My Name and The Fire Next Time both sold more than a million copies; both were cited for their predictions of black violence in desperate response to white oppression. In Encounter, Colin MacInnes concluded that the reason “why Baldwin speaks to us of another race is that he still believes us worthy of a warning: he has not yet despaired of making us feel the dilemma we all chat about so glibly, ... and of trying to save us from the agonies that we too will suffer if the Negro people are driven beyond the ultimate point of desperation.”

Retrospective analyses of Baldwin’s essays highlight the characteristic prose style that gives his works literary merit beyond the mere dissemination of ideas. In A World More Attractive: A View of Modern Literature and Politics, Irving Howe placed the author among “the two or three greatest essayists this country has ever produced.” Howe claimed that Baldwin “has brought a new luster to the essay as an art form, a form with possibilities for discursive reflection and concrete drama. ... The style of these essays is a remarkable instance of the way in which a grave and sustained eloquence—the rhythm of oratory, ... held firm and hard—can be employed in an age deeply suspicious of rhetorical prowess.” “Baldwin has shown more concern for the painful exactness of prose style than any other modern American writer,” noted David Littlejohn in Black on White: A Critical Survey of Writing by American Negroes. “He picks up words with heavy care, then sets them, one by one, with a cool and loving precision that one can feel in the reading. ... The exhilarating exhaustion of reading his best essays—which in itself may be a proof of their honesty and value—demands that the reader measure up, and forces him to learn.”

Baldwin’s fiction expanded his exploration of the “full weight and complexity” of the individual in a society prone to callousness and categorization. His loosely autobiographical works probed the milieus with which he was most familiar—black evangelical churches, jazz clubs, stifling Southern towns, and the Harlem ghetto. In The Black American Writer: Fiction, Brian Lee maintained that Baldwin’s “essays explore the ambiguities and ironies of a life lived on two levels—that of the Negro and that of the man—and they have spoken eloquently to and for a whole generation. But Baldwin’s feelings about the condition— alternating moods of sadness and bitterness—are best expressed in the paradoxes confronting the haunted heroes of his novels and stories. The possible modes of existence for anyone seeking refuge from a society which refuses to acknowledge one’s humanity are necessarily limited, and Baldwin has explored with some thoroughness the various emotional and spiritual alternatives available to his retreating protagonists.” Pratt felt that Baldwin’s fictive artistry “not only documents the dilemma of the black man in American society, but it also bears witness to the struggle of the artist against the overwhelming forces of oppression. Almost invariably, his protagonists are artists. ... Each character is engaged in the pursuit of artistic fulfillment which, for Baldwin, becomes symbolic of the quest for identity.”

Love, both sexual and spiritual, was an essential component of Baldwin’s characters’ quests for self-realization. John W. Aldridge observed in the Saturday Review that sexual love “emerges in his novels as a kind of universal anodyne for the disease of racial separatism, as a means not only of achieving personal identity but also of transcending false categories of color and gender.” Homosexual encounters emerged as the principal means to achieve important revelations; as Bigsby explained, Baldwin felt that “it is the homosexual, virtually alone, who can offer a selfless and genuine love because he alone has a real sense of himself, having accepted his own nature.” Baldwin did not see love as a “saving grace,” however; his vision, given the circumstances of the lives he encountered, was more cynical than optimistic. In his introduction to James Baldwin: A Collection of Critical Essays, Kenneth Kinnamon wrote: “If the search for love has its origin in the desire of a child for emotional security, its arena is an adult world which involves it in struggle and pain. Stasis must yield to motion, innocence to experience, security to risk. This is the lesson that ... saves Baldwin’s central fictional theme from sentimentality. ... Similarly, love as an agent of racial reconciliation and national survival is not for Baldwin a vague yearning for an innocuous brotherhood, but an agonized confrontation with reality, leading to the struggle to transform it. It is a quest for truth through a recognition of the primacy of suffering and injustice in the American past.” Pratt also concluded that in Baldwin’s novels, “love is often extended, frequently denied,

James Baldwin Biography - Childhood, Life Achievements & Timeline

James Baldwin | Poetry Foundation

James Baldwin | Facebook

James Baldwin Biography | List of Works, Study Guides & Essays | GradeSaver

James Baldwin | Encyclopedia.com | Writer

Hottest Creampies

Sissy Foot Worship

Stella Star Porn

James Baldwin Writings

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-57172813-58b892095f9b58af5c2e3f6b.jpg)

c_limit/20191125-James-Baldwin-01.jpg" width="550" alt="James Baldwin Writings" title="James Baldwin Writings">

c_limit/20191125-James-Baldwin-01.jpg" width="550" alt="James Baldwin Writings" title="James Baldwin Writings">