James Baldwin Homosexual

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Even though criticism is increasingly challenging the traditional view of James Baldwin’s earlier novels as “whimsical detours,” these texts continue to be read as “white” and, therefore, studied in sexual rather than racial terms, in (white) gay studies rather than African American studies. Moving beyond these assumptions, however, this article is centrally concerned with race-ing James Baldwin’s early fiction, particularly Giovanni’s Room, illustrating the relevance of race in general to the novel, and of whiteness in particular. While apparently raceless, the novel not only makes whiteness visible as a specific ethnic construct but also illustrates its dependence on other hegemonic categories, particularly masculinity and heterosexuality. More specifically, I will be arguing that in Giovanni’s Room race is deflected onto sexuality with the result that whiteness is transvalued as heterosexuality, just as homosexuality becomes associated with blackness, both literally and metaphorically. Borrowing from recent work on the symbolism of whiteness and/as color, I will show how the white-versus-black dichotomy plays a very meaning-full role in Baldwin’s novel, revealing both descriptive and symbolic (sexual) meanings. In so doing, I attempt to demonstrate that Giovanni’s Room is not (only) about homosexuality but (also) about race. By exploring the color-full associations that Baldwin established between whiteness and heterosexuality on the one hand and homosexuality and blackness on the other, we will see how in Giovanni’s Room the discourses of race and (homo)sexuality are inseparable from each other. Moreover, Baldwin not only depicts the binary oppositions that shape the dominant sexual and racial discourse but also ends up deconstructing them from highly subversive and innovative perspectives. While whiteness has been traditionally opposed to blackness, and even while heterosexuality has usually been constructed in opposition to homosexuality, Giovanni’s Room ultimately reveals their interrelatedness and mutual dependence.

Content uploaded by Josep M. Armengol

Content may be subject to copyright.

[Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2012, vol. 37, no. 3]

䉷2012 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0097-9740/2012/3703-0014$10.00

In the Dark Room: Homosexuality and/as Blackness in

The sexual question and the racial question have always been entwined.

Despite the success of his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953),

James Baldwin had great difficulty in finding a publisher for Gio-

vanni’s Room, his second major fictional text. Alfred A. Knopf had

published Go Tell It on the Mountain but rejected Giovanni’s Room due

to its explicit homosexual content, warning the writer that such a book

“would ruin his reputation...andhewasadvised to burn the manuscript”

(Weatherby 1989, 119). Even though Dial Press finally accepted the novel

in 1956, Baldwin’s text was initially ignored or dismissed as a deviation

in both sexual and racial terms. Published in mid-1950s America, when

the country was dominated by the Cold War discourse against both com-

munists and homosexuals, the critical reception of a homosexual novel

was predictable enough. One of the book’s early reviews was titled “The

Faerie Queenes” (Ivy 1957, 123), and another critic hoped that “Mr.

Baldwin [would] return to...American themes” (West 1956, 220). In

addition to criticizing its overt homosexual content, some scholars com-

plained that the novel, centered on a white homosexual couple, was not

sufficiently focused on the black experience. Nathan A. Scott Jr., for ex-

ample, argued that whereas Go Tell It on the Mountain represented Bald-

win’s “passionate gesture of identification with his people,” Giovanni’s

Room might be read “as a deflection, as a kind of detour” (Scott 1967,

27–28), lamenting that Baldwin’s second novel moved away from his

African American culture and heritage. If many reviewers in the main-

stream press described Baldwin’s new novel as sexually deviant, African

American critics saw it as racially deviant as well.

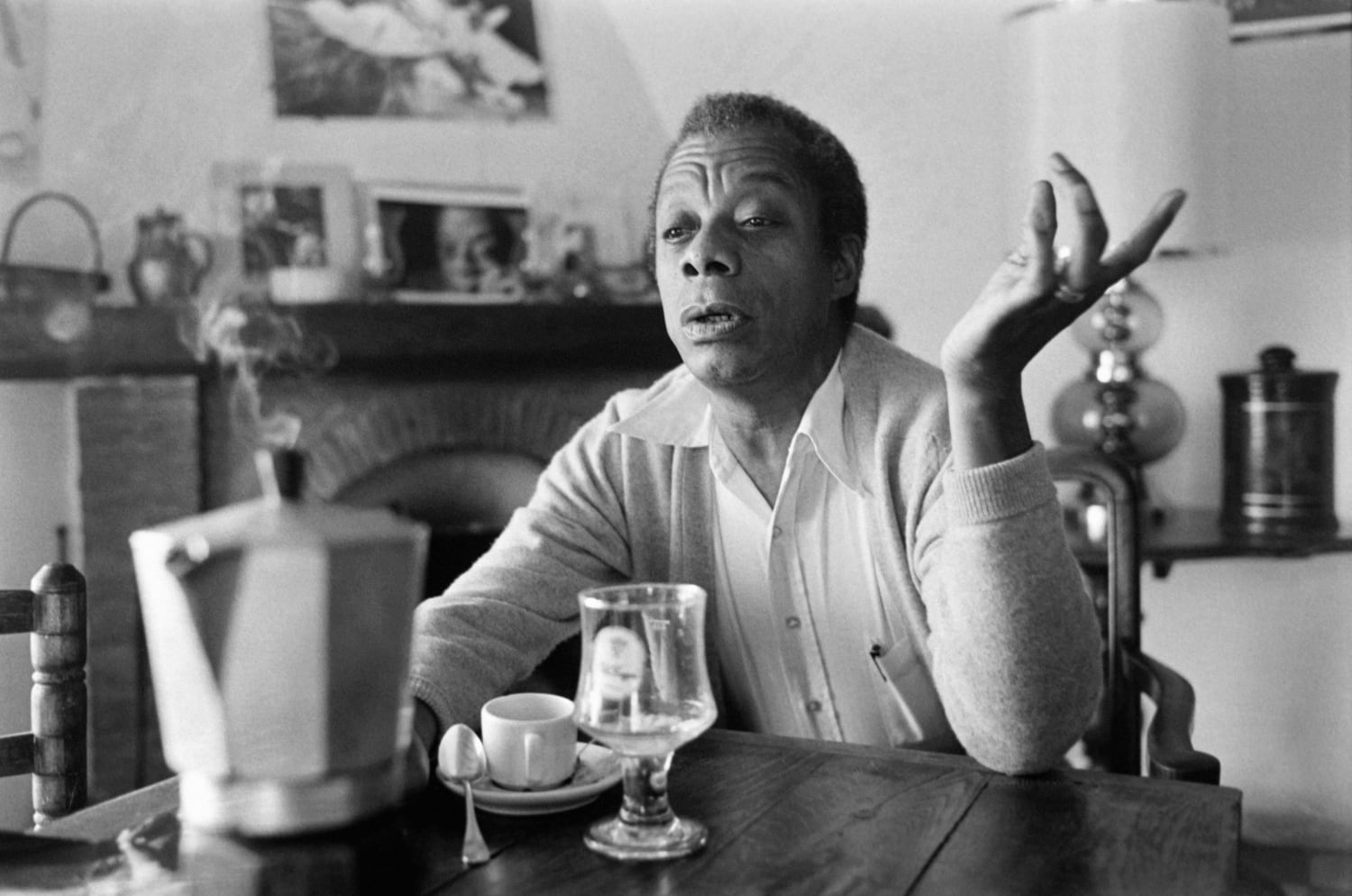

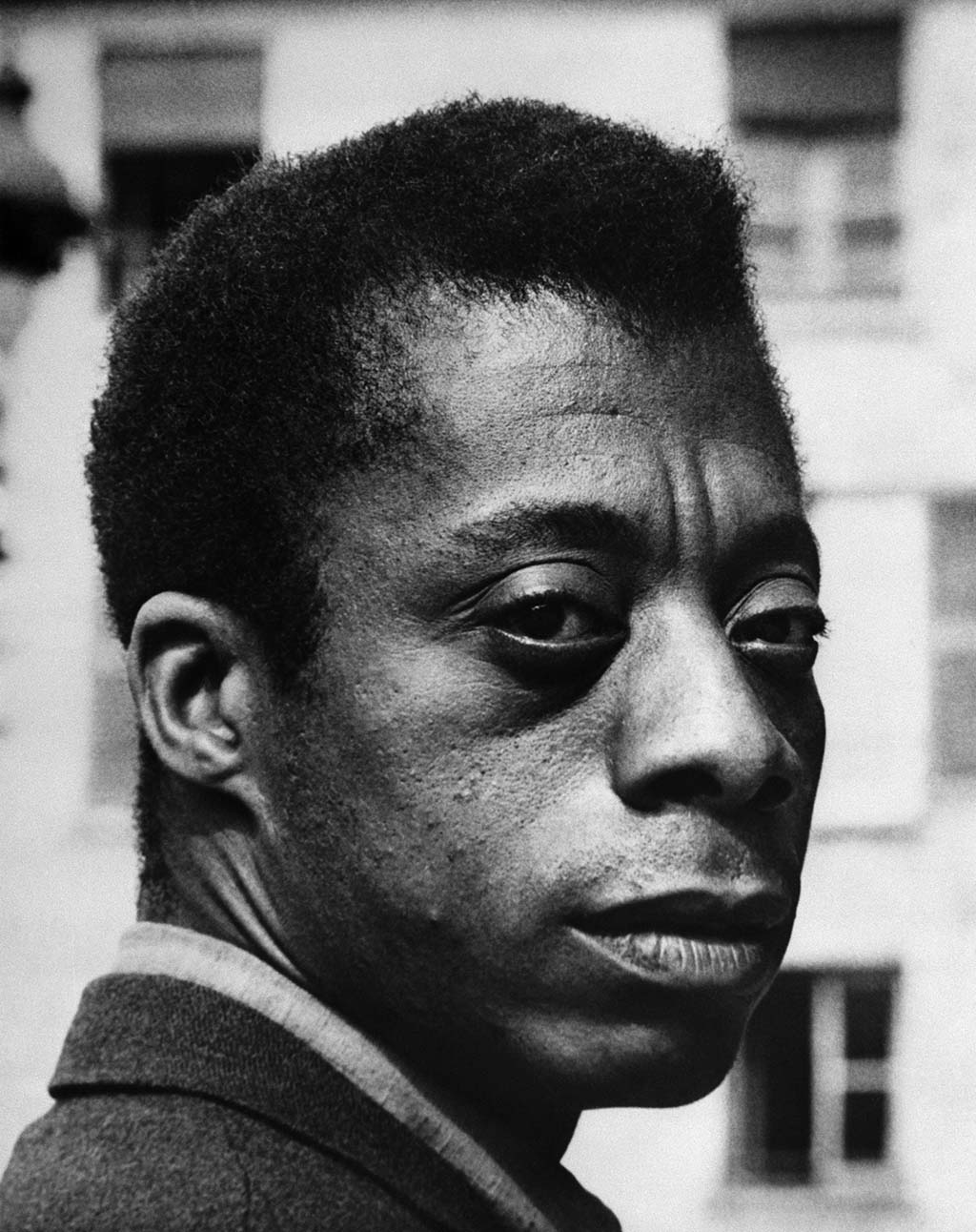

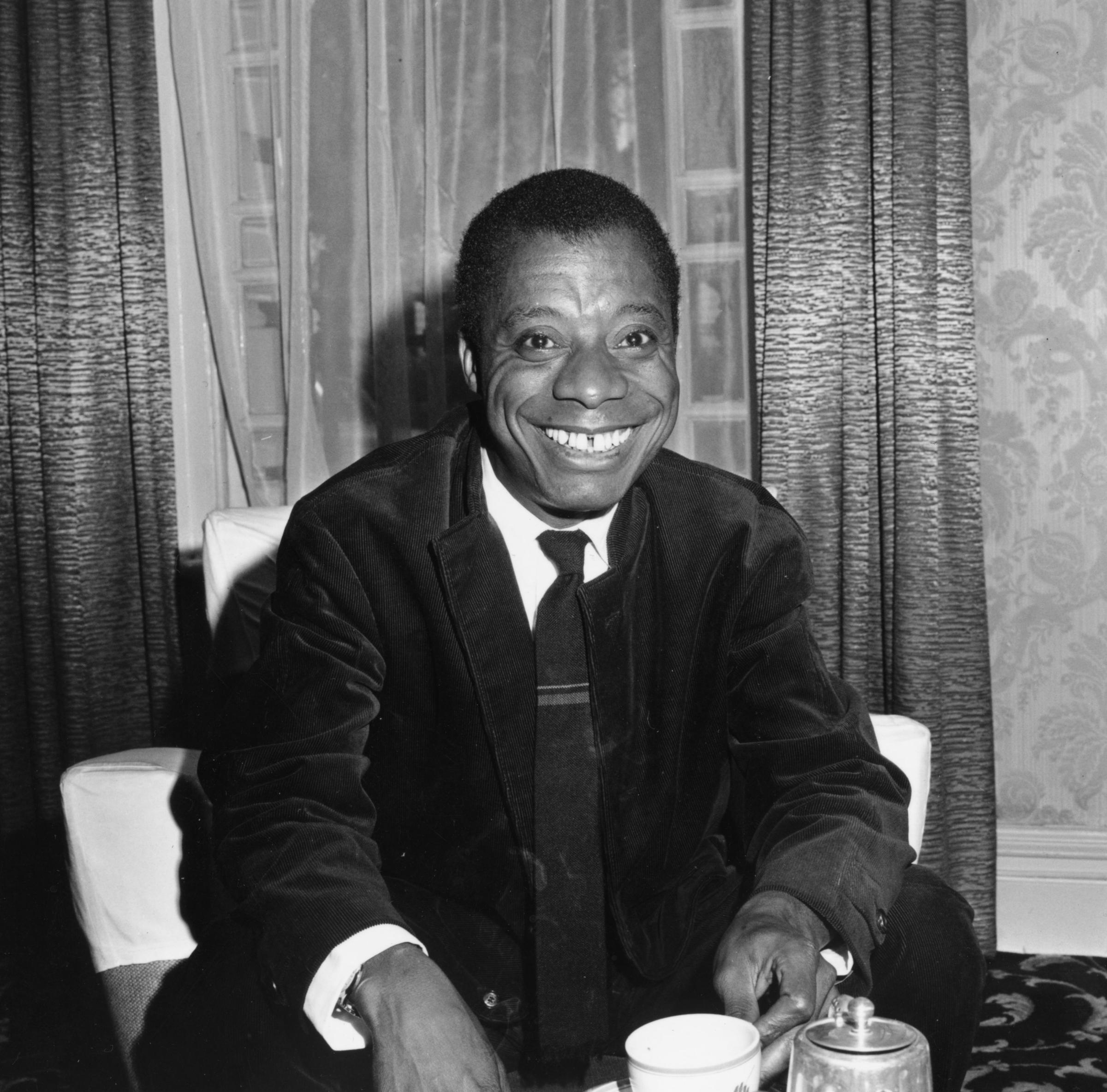

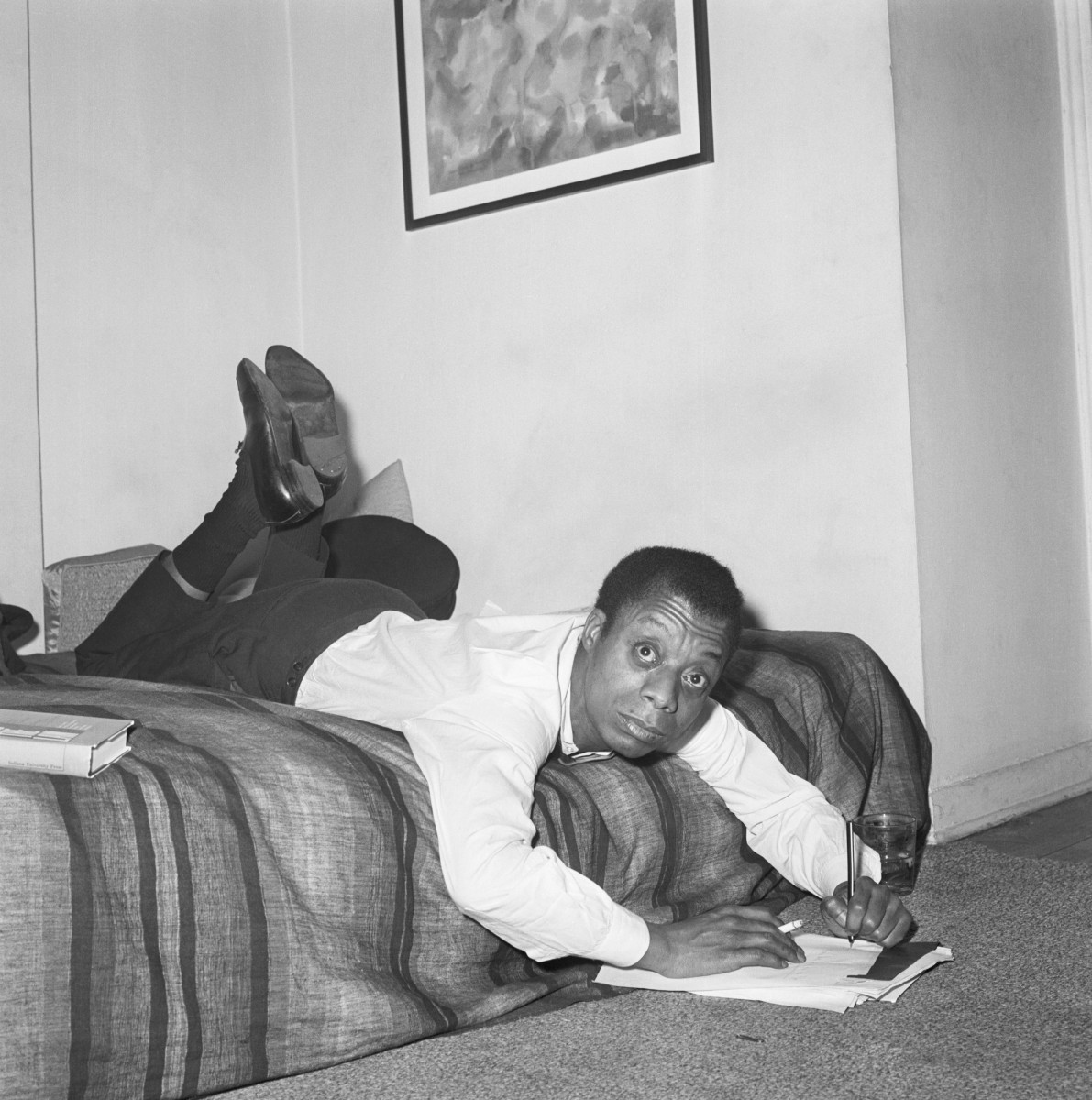

Interestingly, Dial Press decided to exclude Baldwin’s photograph from the text, which,

as James Campbell (1991, 106) has argued, suggests that part of the publisher’s fear was in

having a black man associated with an “all-white” novel—especially one about homosexuality.

ularly black nationalists, went even further, linking Baldwin’s sexual “per-

versions” with racial ones. For example, following the publication of Nor-

man Mailer’s influential text The White Negro (1957), wherein he

celebrates black masculine sexual superiority, Eldridge Cleaver published

his now infamous Soul on Ice (1968), which continued to equate blackness

with heterosexual virility, thereby diminishing black homosexuality in gen-

eral, and Baldwin’s homosexuality in particular, which Cleaver described

as a “racial death-wish” (Cleaver 1968, 103) typical of the black bour-

In Cleaver’s own words: “Many Negro homosexuals, acquiescing

in this racial death-wish, are outraged and frustrated because in their

sickness they are unable to have a baby by a white man. The cross they

have to bear is that, already bending over and touching their toes for the

white man, the fruit of their miscegenation is not the little half-white

offspring of their dreams but an increase in the unwinding of their

nerves—though they redouble their efforts and intake of the white man’s

According to Cleaver, then, black homosexual desire is ultimately desire

for whiteness, desire to abandon black masculinity for the traditionally

submissive position of the white female. If Mailer and white liberalism

idealized blackness as the epitome of masculinity, Baldwin was, neverthe-

less, accused by Cleaver and other black radicals of lacking in masculinity

and, therefore, blackness. Thus, Baldwin’s position in the politics and

culture of the sixties was particularly complex and contradictory. While

playing a key role in the Civil Rights struggle, he was also considered

dangerous and subversive by many of its leaders, who distrusted his sex-

uality. Though a potential candidate for hypermasculinization by virtue

of his race, he was, paradoxically enough, diminished by fellow blacks “for

not being black (read masculine) enough” (Shin and Judson 1998, 250).

Ultimately, then, Baldwin became associated with both sexual and racial

While Baldwin was thus accused of not being black enough, criticism

has since worked to correct such traditional assumptions, redefining his

oeuvre as “a progressive, consistent thinking through,...anintentionally

Similarly, both Richard Wright and Martin Luther King Jr. disparaged Baldwin because

of his homosexuality (Campbell 1991, 71, 175).

Even Langston Hughes, another black gay writer, saw Baldwin’s overt treatment of

homosexuality as a threat to traditional black values. Hughes, who considered it necessary

to sublimate homosexual desire (at least in his novels) for the sake of racial harmony and

wholeness, associated Baldwin’s representations of interracial homo- or bisexuality, partic-

ularly in Another Country, with integration, and integration with the loss of traditional black

politicized engagement rather than a whimsical detour” (Ross 1999, 19).

In Baldwin’s early work, in which overt homosexuality appears to be

mostly associated with whiteness, a reader already uncomfortable with

sexual variance may avoid at least some discomfort by segregating black-

ness from same-sex desire. Baldwin responded to both the racist sexuali-

zation of African Americans by the white community and the homophobia

of the African American community by removing (at least from the sur-

face) the subject of race from much of his early fiction. Baldwin himself

commented in a later interview on Giovanni’s Room that including ho-

mosexuality, the “Negro problem,” and a Paris setting in the same novel

in 1950s America “would have been quite beyond my powers” (Baldwin

1984a, 59). Overall, the “blackening” of Baldwin’s novels has been de-

scribed as “progressive” and “consistent” (Ross 1999, 19).

works usually continue to be regarded as “raceless” (Bone 1965, 238)

and, therefore, studied in sexual rather than racial terms, in (white) gay

studies rather than African American studies. Nevertheless, following the

example set by critics such as Robert F. Reid-Pharr (2001), Marlon B.

Ross (1999), William A. Cohen (1991), and Robert A. Bone (1965),

among others, my own article will be centrally concerned with race-ing

Baldwin’s early fiction, showing the centrality of race in general, and of

whiteness in particular, to Giovanni’s Room, as well as the novel’s depen-

dence on other hegemonic categories, especially masculinity and hetero-

sexuality. More specifically, I will argue that in Giovanni’s Room,asin

Another Country (Baldwin [1962] 1993), race is deflected onto sexuality

with the result that whiteness is transvalued as heterosexuality, just as

homosexuality becomes associated with blackness, both literally and meta-

phorically. Borrowing from recent work on the symbolism of whiteness

and/as color by scholars such as Richard Dyer (2007), Eric Lott (1993),

and Mason Stokes (2001), among others, I will show how the white-

versus-black dichotomy plays a very meaning-full role in Baldwin’s novel,

revealing both descriptive and symbolic (sexual) meanings. By exploring

the color-full associations that Baldwin establishes between whiteness and

heterosexuality, on the one hand, and homosexuality and blackness, on

In contrast to the (white) homosexual relationships engaged in by characters such as

Eric and Yves in Another Country (Baldwin [1962] 1993) or David and Giovanni in Gio-

vanni’s Room, it is not until 1968, with the publication of Tell Me How Long the Train’s

Been Gone, that Baldwin explores overt sexual relations between two black men in a novel,

and not until 1979, with Just Above My Head, his last novel, that he focuses on love between

two black men, both of whom are exclusively homosexual (as opposed to bisexual characters

such as Rufus Scott in Another Country or Leo Proudhammer in Tell Me How Long the

the other, we will see how in Giovanni’s Room the discourses of race and

(homo)sexuality are inseparable from each other. Moreover, Baldwin not

only depicts the binary oppositions that shape the dominant sexual and

racial discourse but also ends up deconstructing them from subversive

and innovative perspectives. While whiteness has traditionally been op-

posed to blackness, and even as heterosexuality has usually been con-

structed in opposition to homosexuality, Giovanni’s Room undermines

such false oppositions by revealing, as we shall see, their interrelatedness

Race-ing sexuality in Giovanni’s Room

Although Giovanni’s Room has traditionally been defined as raceless, a

number of scholars have recently set out to “race” the novel in different

ways. For instance, Reid-Pharr, analyzing the “very apparent absence” of

race in the novel, has shown how Baldwin’s novel is in reality “a race

novel” since Giovanni’s “ghost-like nonpresence, his nonsubjectivity,” re-

flects the absence of blackness from Western notions of rationality and

humanity (Reid-Pharr 2001, 126). Similarly, Myriam J. A. Chancy (1997)

has explored the race component of the novel by comparing Giovanni’s

Room to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, just as Horace A. Porter (1989)

has connected Baldwin’s novel to Richard Wright’s Native Son, suggesting

that “Baldwin...smuggles into Giovanni’s Room, a place where we least

expect them, Native Son’s central themes, images and symbols” (151). If

scholarship has thus begun to challenge the traditional view of Giovanni’s

Room as raceless, I will be arguing that race and sexuality in Baldwin are

not simply interrelated but virtually interchangeable so that homosexuality

becomes, literally and metaphorically, associated with blackness at the same

time that heterosexuality is, as we shall see, indissolubly linked to white-

ness. Some scholars, perhaps most notably Kemp Williams (2000) and

Philip Auger (2000), have already explored the metaphorical construction

of sexuality and/or race in the text. Williams (2000), for example, illus-

trates Baldwin’s use of spaces and objects—such as the body, mirrors and

windows, and Giovanni’s room itself—as metaphors for David’s repressed

homosexuality. Auger, for his part, goes even further, arguing for the

deflection of race onto sexuality in the novel. Even though David is not

a black man, the problems he faces, according to Auger (2000), are best

defined in terms that would equally fit a black man: “‘no place’—except

closeted, contained places—exists for him either” (17). While some schol-

ars have thus explored the novel’s sexual and/or racial displacements,

which appear to place black souls in white bodies, much less attention

seems to have been paid to the meanings, both literal and metaphorical,

of color in the text, particularly in relation to sexuality. Traditionally, color

has been taken as a surface matter in Giovanni’s Room and has thus been

regarded as a matter of mere description rather than as a meaning-full

symbol. However, if one concurs with Ross (1999, 25–26) that Baldwin

refers to color as a way of locating the cultural situation, both racial and

sexual, of his characters, then it should be possible to read Baldwin’s novel

in a new light, exploring the connections that the writer both draws and

undermines between blackness and homosexuality, on the one hand, and

whiteness and heterosexuality, on the other. As Ross himself elaborates:

Baldwin examines how desire becomes coded and enacted among

a particular group of men whose racial heritage shapes attitudes

toward sex, romance, love, and friendship. This reading of the novel

gives depth to what otherwise must remain on the surface: the color

casting (stereotyping even) of the characters’ personalities....Itis

not only each character’s sexual identity that makes him represen-

tative or unique but also/instead his racial difference, coded as ethnic

and sexual identity. Without the ethnic difference between Giovanni,

the impulsive Italian, and David, the methodical Teuton, it would

be impossible for the novel to script its story of tortured same-sex

Crucially, then, Ross not only underlines, as several other critics have, the

connections between sexual and racial identity in Baldwin but also draws

attention to another important fact that is usually overlooked—namely, the

influence of color on same-sex attraction in Giovanni’s Room, “where the

color dilemma is mapped onto the question of same-sex desire” (Ross 1999,

33). In Baldwin’s second novel, sexuality, both homosexual and hetero-

sexual, does indeed seem to be inextricably bound to color, particularly

the white-versus-black dichotomy, whose occurrence is both physical and

symbolic. As we shall see, Giovanni’s Room suggests a parallel between

the heterosexual and white (with its metaphorical associations with light,

cleanness, purity, rationality, transparency, goodness, innocence, etc.), on

the one hand, and the homosexual and black (with its symbolic meanings

of darkness, dirt, sin, emotionality, obscurity, evil, guilt, and so on), on

the other, a parallel that Baldwin simultaneously reinscribes and problem-

In White (2007), his pathbreaking analysis of whiteness in Western

society and culture, Richard Dyer has demonstrated the centrality of no-

tions of color to white representation. As he explains, there are three

senses of whiteness as color (Dyer 2007, 45–46). First of all, white is a

category of color or hue, just like red or green. Second, white is a category

of skin color. Third, white, like any other hue, has symbolic connotations.

In this last respect, Dyer suggests that, despite some national and historical

variation, the basic symbolic connotation of white is fairly clear, its most

familiar form being the moral opposition of white pgood and black p

bad. Exploring how questions of color become entangled with questions

of morality, Dyer demonstrates that dark-haired characters tend to be more

wicked and sensual than fair-haired and light-complexioned ones. To be

white is to be at once of the white race and “honorable” and “square

dealing,” whereas to be black is just the opposite. In Dyer’s words, “a

white person who is bad is failing to be ‘white,’ whereas a black person

who is good is a surprise, and one who is bad merely fulfils expectations”

(63). Elaborating on the symbolic meanings of whiteness, Dyer shows

how, in Western tradition, lists of the moral connotations of white as

symbol are remarkably similar: spirituality, transcendence, innocence,

cleanliness, simplicity, and so on. Since to be white is to be clean, blackness

is, by contrast, associated with dirt, the dark color of feces reinforcing the

connotation of blackness with badness. In Dyer’s own words, “to be white

is to have expunged all dirt, faecal or otherwise, from oneself: to look

Because of the association of whiteness with cleanliness, and its meta-

phorical connotations of chastity and purity, sexual desire has traditionally

been defined as itself dark. “Darkness,” as Lynne Segal (1990) puts it,

has “always been entangled—in Western consciousness—with sex....

Black is the colour of the ‘dirty’ secrets of sex” (176). While white men

have traditionally identified white women with the model of the Virgin

Mary, whose purity is unsullied by the dark drives of sexuality, they have

also projected their sexuality onto dark races as a means of representing

their own desires while keeping those desires at a distance. In a way, then,

sexuality has been culturally defined as a disturbance of racial purity. As

Dyer writes, “the very thing that makes us white endangers the repro-

duction of whiteness” (Dyer 2007, 27).

Yet even as both white men and women have tried to dissociate them-

selves from sexual desire, representing it as dark, white people need, none-

theless, to have sex in order to ensure the survival of the race. Moreover,

not to be sexually driven can call into question a man’s masculinity. Thus,

white men insure both their whiteness and masculinity by channeling their

sexual desire into heterosexual marriage and reproduction. Ultimately,

then, heterosexuality, as Dyer himself concludes, constitutes “the cradle

of whiteness” (2007, 140). Indeed, whiteness, as Stokes demonstrates in

The Color of Sex: Whiteness, Heterosexuality, and the Fictions of White

Supremacy (2001), appears to work “best—in fact, it works only—when

it attaches itself to other abstractions,” particularly heterosexuality, “be-

coming yet another invisible strand in the larger web of unseen yet pow-

erful cultural forces” (13). Analyzing its location within a larger system

of oppressive and regulatory structures, Stokes shows how whiteness re-

mains inseparable from heterosexuality, since each depends on the other

to promote its own invisibility and normalizing power. As Stokes con-

cludes, “heterosexuality gives birth to whiteness. . . . It nurtures whiteness,

attending to its needs and soothing away its anxieties” (21) so that “the

study of whiteness...gives us a new and richer way of thinking about

In Giovanni’s Room, it is David who embodies the ideal of whiteness.

Tall and blond-haired, he identifies himself from the start as the descen-

dant of white colonizers: “I watch my reflection in the darkening gleam

of the window pane. My reflection is tall...myblond hair gleams. My

face is like a face you have seen many times. My ancestors conquered a

continent, pushing across death-laden plains, until they came to an ocean

which faced away from Europe” (Baldwin [1956] 1964, 7). While much

of Giovanni’s Room focuses on the homosexual relationship b

Homosexuals and James Baldwin's Role in the Civil Rights... | Bartleby

(PDF) In the Dark Room: Homosexuality and/as Blackness in James...

James Baldwin (writer) | LGBT Info | Fandom

GAY.RU - Джеймс Болдуин (1924-1987)

James Baldwin's Most Famous LGBT Novel - YouTube

Liya Kebede Nude

Free Ebony Hub

Sissy Training Chastity

James Baldwin Homosexual

c_limit/James-Baldwin-Acyde-on-James-Baldwin's-Righteous-Style-GQ020119-GYOL-05-social.jpg" width="550" alt="James Baldwin Homosexual" title="James Baldwin Homosexual">

c_limit/James-Baldwin-Acyde-on-James-Baldwin's-Righteous-Style-GQ020119-GYOL-05-social.jpg" width="550" alt="James Baldwin Homosexual" title="James Baldwin Homosexual">

c_limit/181203_r33321.jpg" width="550" alt="James Baldwin Homosexual" title="James Baldwin Homosexual">

c_limit/181203_r33321.jpg" width="550" alt="James Baldwin Homosexual" title="James Baldwin Homosexual">