Ishmael Moby Dick

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

In Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, Ishmael asserts himself as both the narrator and the central consciousness of the novel by chronicling his account of the Pequod’s final voyage. As he recounts the struggles of his physical journey, Ishmael shows that he has also survived a spiritual journey to find his sense of self. By retelling and analyzing his time as a crewmember of the Pequod, Ishmael continues to try to understand the purpose behind his solitary existence and eventually embraces it as a part of God’s mysterious Providence.

Ishmael sees himself as an exile of the world who is doomed to drift without a home to return to. He begins his narration by naming himself after a Biblical figure: “Call me Ishmael” (Melville 18). The lack of last name suggests that like Abraham’s first and lesser loved son, Ishmael has been un-rooted and thrown out of his family. He considers himself to be an orphan, although he uses the word only at the conclusion of his journey when he is left as the sole survivor: “It was the devious-cruising Rachel… only found another orphan” (427). This sentiment demonstrates the loss he has experienced through the Pequod’s shipwreck and the affinity he felt for its crew. In contrast, the only family member who describes in his narration is his “stepmother who, somehow or other, was all the time whipping me, or sending me to bed supperless,” and who isolates Ishmael even within his house (37). This forced physical separation is what prevents him from regarding the house he grew up in as home and which keeps him drifting without a sense of belonging. This loneliness develops into isolation, which causes Ishmael to separate himself from others and observe them from a distance. This allows him to see beyond conventional beliefs and question societal norms, but also deepens his isolation.

This text is NOT unique. Don't plagiarize, get content from our essay writers!

This isolation continues to trouble Ishmael throughout the years, to the extent that he considers it deadly. When his stepmother punishes him by sending him to bed, he describes that he “lay there dismally…before I could hope for resurrection,” comparing the isolation to death (37). He emphasizes how much he hates this solitary confinement by begging for any other punishment but burial in bed, because the maddening boredom that comes from isolation causes him to feel like dying a painful, spiritual death. This lonely boredom causes him to view his life as being so meaningless that he feels himself driven to the breaking point, even to the point of considering suicide, “involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral” he encounters (18). But instead of giving in to this impulse, he chooses to go to sea as a “substitute for pistol and ball” (18). This voyage onto the water symbolizes his desire to revive himself and to get back in touch with himself and humanity. He seeks an end to his perceived isolation and believes that he may do so on the water, where “here they all unite” (19). To Ishmael, the attraction to water is one of the universal characteristics of men, representing their common desire to see meaning and purpose in the reflections they cast, and to catch the “ungraspable phantom of life” that eludes us all (20). As he observes that these “water-gazers” spiritually unite, he realizes that the sea unites people even in their most isolated moments (43). This idea is further emphasized when he sees people looking at the gravestones in the chapel unite through the “silent grief” that “were insular and incommunicable,” caused by the sense of vulnerability and mortality of the sailors at sea (43). Once he joins the Pequod, he proclaims “I, Ishmael, was one of that crew; my shouts had gone up with the rest; my oath had been welded with theirs” (152). Unlike on land, where Ishmael drifts without aligning himself to anyone or any cause, he becomes committed to Ahab’s quest, and this becomes his purpose for the duration of the voyage.

Captain Ahab’s greatest influence over Ishmael does not result from direct interaction, but rather from Ishmael’s observations of Ahab’s struggles against himself and against the world. Ishmael clearly sees that Ahab’s obsession with Moby Dick has driven him to madness, and that he believes that control over this madness is beyond the boundaries of his free will. When Ahab questions “Is Ahab, Arab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm?” Ishmael sees Ahab’s confusion in his identity, between the Ahab who desires to return to his family and the Ahab who is destined to spend his life chasing Moby Dick (406). This concept of free will against fate becomes an important theme in Ishmael’s narrative. As Ahab gets closer to Moby Dick, he becomes completely consumed by the idea of destroying all evil through Moby Dick, allowing Fate to take over his free will, as Ahab concludes that his identity is the “Fates’ lieutenant” who “act under orders,” and not his free will (418). Ishmael, who observes the tangling of free will and fate through Ahab, begins to understand that God’s will comes in the form of “springs and motives which being cunningly presented to me induced me to set about performing the part I did, besides cajoling me into the delusion that it was a choice resulting from my own unbiased freewill and discriminating judgment” (22). In short, while people may believe they act on their own accord, these actions are actually predetermined by God.

Ahab’s comparison of life to a play also resonates with Ishmael. When he recalls that Ahab said, “This whole act’s immutably decreed. ‘Twas rehearsed by thee and me a billion years before this ocean rolled” Ishmael sees that Ahab believes that his endless quest for revenge against Moby Dick was preordained (418). This causes Ishmael to consider his own role in the voyage, perceiving that “my going on this whaling voyage, formed part of the grand programme of Providence that was drawn up a long time ago” and “those stage managers, the Fates, put me down for this shabby part of a whaling voyage” (22, 418). Although he sees his own role as a “shabby” one and compares himself to others who were cast for “magnificent roles in high tragedies” and “short and easy parts in genteel comedies”, he accepts his fate, and in doing so, he shows that he understands that is life is not without meaning. Even the boredom and loneliness that has constantly plagued him now take the form as catalysts for his joining the Pequod. As Ishmael begins considering the role of God’s Providence in his life, he is still unable to grasp its true significance. However, by looking back at the series of decisions it took for him to join the Pequod, Ishmael begins to understand “the springs and motives which… induced me to set about performing the part I did,” that even his loneliness and isolation has a greater end as a part of the God’s plan (22).

In fact, fate, destiny, and Providence go beyond the boundaries of Christianity for Ishmael and allows him to eventually see and treat Queequeg without prejudice. Although he, like most of his compatriots, was initially terrified of Queequeg, the friendly affection that he shows to Ishmael wins him over. After observing Queequeg’s character and noting that this supposed savage seemed to “have an innate sense of delicacy” and proved “essentially polite”, Ishmael compares him with the Christians he has known (38). He remarks that “Christian kindness has proved but hollow courtesy” and questions who is truly the more civilized (56). Eventually, he concludes that religious worship comes in the form of obeying the will of God, and that what God essentially requires of men is “to do to my fellow man what I would have my fellow man do to me” (57). This allows him to realize that like Ishmael, Queequeg craves understanding and acceptance which Ishmael decides to give. In this way, it is Ishmael’s loneliness and his craving for human connection that allow him to be open minded about living so closely with a cannibalistic heathen. Without any special attachments to Western religion, culture, or societal norms, Ishmael sees beyond Queequeg’s fierce appearance and appreciate his humanity and compassion. Queequeg reciprocates these feelings, and it is the coffin he builds that eventually saves Ishmael’s life.

Ishmael suggests that God facilitated his intimacy with Queequeg so that he could emerge as the sole survivor of the Pequod. In hindsight, Ishmael believes he was “mysteriously drawn towards” Queequeg and that the bond between them goes beyond human comprehension (56). He frequently alludes to marriage, describing their relationship as one that “naught but death should part us twain” and marveling that “he would gladly die for me” (38, 56). The strength of their bond surprises even Ishmael, and in Queequeg, he finally find the closest thing to familial love that he has ever experienced. Furthermore, Ishmael describes how Queequeg’s coffin “liberated by reason of its cunning spring…the coffin life-buoy…floated by my side” it transforms from a container of death to a chance at resurrection ? the same sort of resurrection that Ishmael desired from his cruel exile to bed during his childhood (427). To Ishmael, Queequeg’s death allowed Ishmael to live, and this sacrifice gives his lonely existence value and significance.

By the time he finishes retelling his account, Ishmael has grown from a lonely and restless young man to a mature man who now understands that he has a place in God’s Providence. He sees that his isolation has shaped him into an individual capable of observing and assessing situations objectively, and it has prepared him to fulfill God’s plan that he live to retell his narrative. However, just as Ahab fell to his demise without fulfilling his quest to master Moby Dick, Ishmael cannot fully understand the mysteries of his existence while he remains alive (20). Although Ishmael now recognizes that, this reflection of self in the water that “is the key to it all” (20) still compels him to continue searching for further meaning, leading to the retelling and revisiting of his journey.

Before long, the storyteller discovers Clifton in the city offering Sambo dolls. Clifton has left the gathering. White policemen question Clifton, who does not have an allow to offer things […]

The white paint and the Sambo doll are symbols in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man that emphasizes the futility of finding one’s identity in a world that forces their perspectives onto […]

Blindness is defined as the lack of perception, awareness, and ignorance one might endure during a time of uncertainty. The novel Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, illustrates the narrator’s journey […]

Secondly, the book also reveals many examples of the types of social restriction and lack of economic power blacks have during this time. For instance, African Americans have a much […]

The Author and His/Her Times: Ralph Ellison, born on March 1, 1914 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma wrote The Invisible Man while at a friend’s farm in Vermont. Ellison was named […]

Often in today’s society people become invisible due to their race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or social class. The spirit of the book, Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, is […]

Moby Dick tells the story of a former schoolteacher called Ishmael, who joins a whaling voyage after a severe bout of depression. He befriends Queequeq, a harpooner, and the two […]

Herman Melville began working on his novel Moby Dick in 1850, intending to write a report about the whaling voyages. In Moby-Dick, the story revolves around young Ishmael. Ishmael sacrificed […]

The perception of the white whale, Moby Dick, in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick conveys a message that becomes specific to the reader. The profundity of the white whale, when taken […]

In Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, Ishmael asserts himself as both the narrator and the central consciousness of the novel by chronicling his account of the Pequod’s final voyage. As he recounts […]

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Essay (any type)

Admission essay

Annotated bibliography

Argumentative essay

Article review

Biographies

Book/movie review

Business plan

Capstone project

Case study

Coursework

Creative writing

Critical thinking

Dissertation

Dissertation chapter - Conclusion

Dissertation chapter - Discussion

Dissertation chapter - Introduction

Dissertation chapter - Literature review

Dissertation chapter - Methodology

Essay (any type)

Java programming

Lab report

Other (enter below)

Personal statement

Presentation or speech

Research paper

Research proposal

Resume/CV

Term paper

Thesis

Thesis/Dissertation abstract

Thesis/Dissertation chapter

Thesis/Dissertation proposal

Web-design

Wedding/Graduation Speech

University

High school

College

University

Masters

PhD

14 days

3 h

8 h

24 h

48 h

3 days

5 days

7 days

10 days

14 days

Get tips and ideas in OUTLINE.

Special offer for LiteratureEssaySamples.com readers.

We are using cookies to give you the best experience on our website.

You can find out more about which cookies we are using or switch them off in settings.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Из Википедии, бесплатной энциклопедии

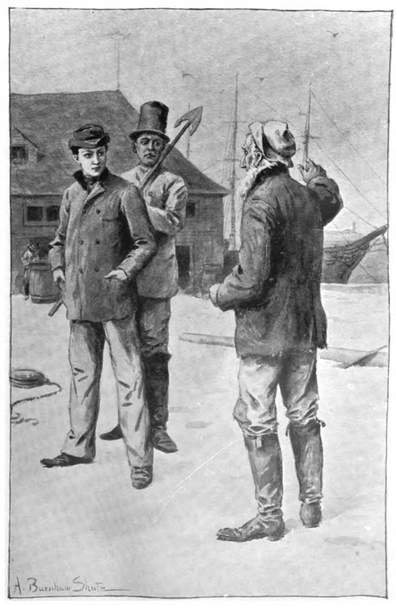

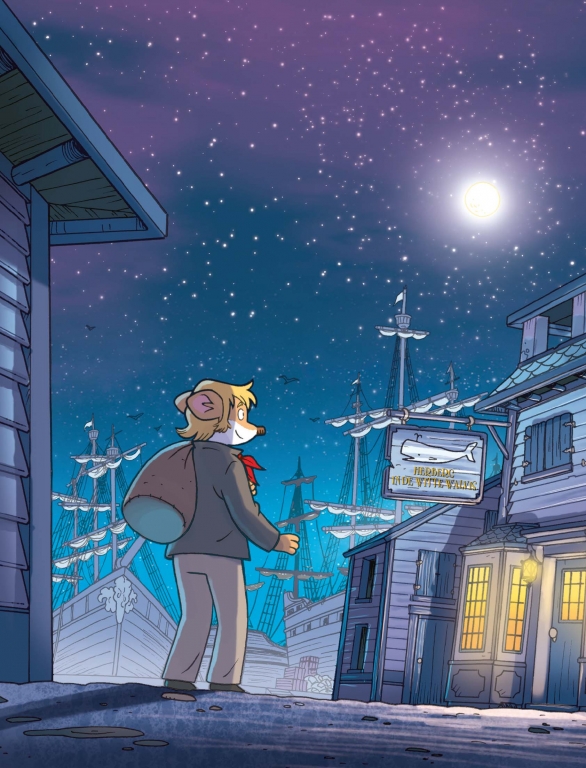

Измаил (слева) изображен в издании книги 1920 года.

Ишмаэль является персонажем в Herman Melville «s Моби Дик (1851), который открывается с линией,„Позвони мне Измаил.“ Он - рассказчик от первого лица в большей части книги. Однако Измаил играет второстепенную роль в сюжете, и ранние критики « Моби-Дика» предполагали, что главным героем является капитан Ахаб . Многие либо путали Измаила с Мелвиллом, либо упускали из виду его роль. Более поздние критики отличали Измаила от Мелвилла, и некоторые считали его мистическое и умозрительное сознание центральной силой романа, а не мономаниакальной силой воли капитана Ахава .

Библейское имя Измаил стало символом сирот, изгнанников и социальных изгоев. В отличие от своего тезки из Книги Бытия , изгнанного в пустыню, Измаил Мелвилла бродит по морю. Однако каждый Измаил переживает чудесное спасение; в Библии от жажды, здесь от утопления.

И Ахав, и Измаил очарованы китом, но в то время как Ахав воспринимает его исключительно как зло, Измаил сохраняет непредвзятость. У Ахава статичное мировоззрение, слепое к новой информации, но мировоззрение Измаила постоянно меняется по мере появления новых идей и осознаний. «А переменчивость, в свою очередь ... является главной характеристикой самого Измаила». В главе «Дублон» Измаил сообщает, как каждый зритель видит свою личность, отраженную в монете, но не смотрит на нее сам. Четырнадцатью главами позже, в «Гульдене», он участвует в «том, что явно является повторением» предыдущей главы. Разница в том, что поверхность золотого моря в «Гульдене» живая, а поверхность дублона неизменно фиксирована, «лишь одно из нескольких контрастов между Измаилом и Ахавом».

Измаил медитирует на широкий круг тем. В дополнение к явно философским ссылкам, в главе 89, например, он излагает юридическую концепцию «Fast-Fish и Loose-Fish», которая, по его мнению, означает, что владение, а не моральное требование, дает право собственности. .

Измаил объясняет, что ему нужно отправиться в море и отправиться с острова Манхэттен в Нью-Бедфорд . Он опытный моряк, в прошлом служивший на торговых судах , но на борту китобойного судна он впервые . Гостиница переполнена , и он должен делить кровать с татуированной полинезийской , Квикег , в harpooneer которого Ишмаэль предполагает быть каннибалом. На следующее утро Измаил и Квикег направляются в Нантакет . Измаил подписывается на рейс на китобойном судне « Пекод» под командованием капитана Ахава. Ахав одержим белым китом Моби Диком, который во время предыдущего плавания отрубил ему ногу. В своем стремлении отомстить Ахав потерял всякое чувство ответственности, и когда кит топит корабль, все члены экипажа тонут, за исключением Измаила: «И я спасся только один, чтобы сказать тебе» (Иов) гласит эпиграф. . Измаил держится на плаву в гробу, пока его не подберет другой китобойный корабль, Рэйчел .

Имя Измаил имеет библейское происхождение: в Бытие 16: 1-16; 17: 18-25; 21: 6-21; 25: 9-17, Измаил был сыном Авраама от рабыни Агари . В 21: 6-21, наиболее важных стихах аллегории Мелвилла, Агарь была отвергнута после рождения Исаака , который унаследовал завет Господа вместо своего старшего сводного брата.

Мелвилл формирует свою аллегорию библейскому Измаилу следующим образом:

Это имя также указывает на библейскую аналогию, которая отмечает Измаила как прототипа «странника и изгоя», человека, враждующего со своими собратьями. Наталия Райт говорит, что все герои Мелвилла, за исключением Бенито Серено и Билли Бадда, являются воплощениями библейского Измаила, и четверо фактически отождествляются с ним: Редберн, Измаил, Пьер и Питч из «Доверительного человека» .

В первые десятилетия возрождения Мелвилла читатели и критики часто путали Измаила с Мелвиллом, работы которого воспринимались как автобиография. Критик Ф.О. Маттиссен еще в 1941 году жаловался, что «большая часть критики наших прошлых мастеров была небрежно привязана к биографиям», и возражал против «современной ошибки» «прямого прочтения личной жизни автора в его произведениях». В 1948 году Говард П. Винсент в своем исследовании «Попытка Моби-Дика » «предостерег от забвения рассказчика», то есть предполагая, что Измаил просто описывает то, что он видел. Роберт Зеллнер отметил, что роль Измаила как рассказчика «рушится» либо тогда, когда Ахав и Стабб «разговаривают сами по себе» в главе 29, либо когда Измаил сообщает «монолог Ахава, сидящего в одиночестве» в главе 37.

Мнения также расходятся относительно того, является ли главный герой Измаилом или Ахавом. М. Х. Абрамс считает, что Измаил является «лишь второстепенным или второстепенным» участником рассказываемой им истории, но Уолтер Безансон утверждает, что роман не столько об Ахабе или Белом ките, сколько об Измаиле, который является «настоящим центром смысла». и определяющая сила романа ».

Безансон утверждает, что есть два Измаила. Первый - это рассказчик, «всеобъемлющая чувственность романа» и «воображение, через которое проходят все дела книги». Читателю не сообщается, через какое время после путешествия Измаил начинает рассказывать о своем приключении. Единственным ключом к разгадке является второе предложение «несколько лет назад». «Второй Измаил», - продолжает Безансон, - это «бачок Измаил» или «младший Измаил« несколько лет назад »... Рассказчик Измаил - это просто молодой Измаил, который стал старше». Форекасл Измаил - «просто один из персонажей романа, хотя, разумеется, главный, чье значение, возможно, не уст

Sex Download Mobile

Eng Zor Va Eng Yosh Sex

Reallifecam Threesome Sex

Pussy Solo 1080p

Lil Peep Sex Last

Ishmael (Moby-Dick) - Wikipedia

Ishmael in Moby-Dick: Character Analysis & Symbolism ...

Ishmael in Herman Melville's "Moby-Dick" | Literature ...

Измаил ( Моби-Дик ) - Ishmael (Moby-Dick) - xcv.wiki

Character Analysis of Ishmael in Moby Dick Herman Melville ...

Ishmael - CliffsNotes

Ishmael Character Analysis in Moby-Dick | SparkNotes

Ishmael in Moby Dick | Literature Essay Samples

Ishmael in Herman Melville's "Moby-Dick" - Free Essay ...

Ishmael Moby Dick

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-sltrib.s3.amazonaws.com/public/RB64NAW345BAXKVKZRPUXRMNIE.jpg)