Isabella Reign

👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

^ Jump up to: a b c d Historia de España . Carr, Raymond., Gil Aristu, José Luis. Barcelona: Ediciones Península. 2001. ISBN 84-8307-337-4 . OCLC 46599274 . CS1 maint: others ( link )

^ Jump up to: a b c d e Vilches García, Jorge. (2001). Progreso y libertad : el Partido Progresista en la revolución liberal española . Madrid: Alianza Editorial. pp. 37–38. ISBN 84-206-6768-4 . OCLC 48638831 .

^ Jump up to: a b Vilches García, 2001, p. 39

The reign of Isabella II of Spain is the period of the modern history of Spain between the death of Ferdinand VII of Spain in 1833 and the Spanish Glorious Revolution of 1868, which forced Queen Isabella II of Spain into exile and established a liberal state in Spain. [1]

On the death of Ferdinand VII on 29 September 1833, his wife María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias assumed the regency with the support of the liberals, on behalf of their daughter and future queen, Isabella II. Conflict with her brother-in-law, Carlos María Isidro de Borbón , who aspired to the throne by virtue of a supposedly valid Salic Law – already repealed by Carlos IV and Ferdinand VII himself – led the country into the First Carlist War. [2]

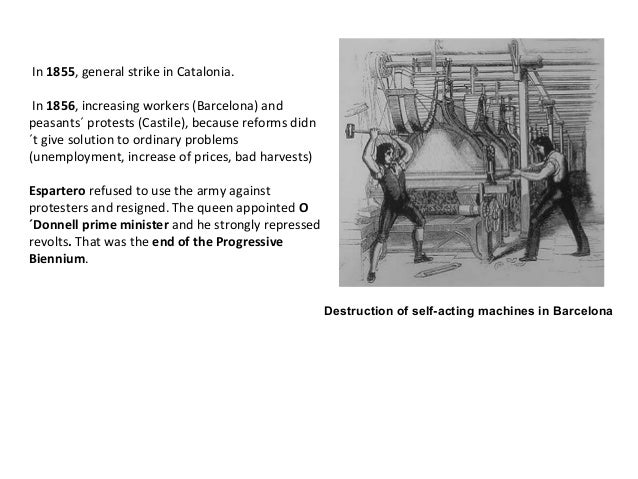

After the brief regency of Espartero, which succeeded the regency of María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias, Isabella II was proclaimed of age at the age of thirteen by resolution of the Cortes Generales in 1843. Thus began the effective reign of Isabella II, which is usually divided into four periods: the moderate decade (1844–1854); the progressive biennium (1854–1856); the period of the Liberal Union governments (1856–1863) and the final crisis (1863–1868).

The reign of Isabella II was characterised by an attempt to modernise Spain which was contained, by the internal tensions of the liberals, the pressure that continued to be exerted by the supporters of more or less moderate absolutism, the governments totally influenced by the military establishment and the final failure in the face of the economic difficulties and the decline of the Liberal Union which led Spain into the experience of the Democratic Sexenio. Her reign was greatly influenced by the personality of Queen Isabella, who had no gifts for government and was under constant pressure from the Court, especially from her own mother, and also from Generals Narváez, Espartero and O'Donnell, which prevented the transition from the Old Regime to the Liberal State from being consolidated, and Spain reached the last third of the 19th century in unfavourable conditions compared to other European powers.

The reign of Isabella II was divided into two major stages:

The Regency of María Cristina de Borbón was marked by the civil war arising from the succession dispute between the supporters of the future Isabel II or "Isabelinos" (or "Cristinos" after the name of the regent) and those of Carlos María Isidro or "Carlists". Francisco Cea Bermúdez, who was very close to the absolutist theses of the late Ferdinand VII, was the first President of the Council of Ministers. The absence of liberal gains forced the departure of Cea and the arrival of Martínez de la Rosa, who convinced the Regent to enact the Royal Statute of 1834, a charter granted that did not recognise national sovereignty, which was a step backwards compared to the Constitution of Cadiz of 1812 , granted by Ferdinand VII . [2]

The failure of the conservative or "moderate" liberals brought the progressive liberals to power in the summer of 1835. The most prominent figure of this period was Juan Álvarez Mendizábal , a politician and financier of great prestige who institutionalised the "revolutionary juntas" that had arisen during the liberal revolts of the summer and initiated several economic and political reforms, including the confiscation of the property of the regular orders of the Catholic Church. During the second progressive government presided over by José María Calatrava and with Mendizábal as the strong man in the Treasury portfolio, the new Constitution of 1837 was approved in an attempt to combine the spirit of the Cadiz Constitution and achieve consensus between the two main liberal parties, moderates and progressives.

The Carlist War caused serious economic and political problems. The fight against the army of the Carlist Tomás de Zumalacárregui , who had been in arms since 1833, forced the Regent to place a large part of her trust in the Christian military, who achieved great renown among the population. One of these was General Espartero , who was responsible for certifying the final victory in the Oñate Agreement , better known as the Abrazo de Vergara (the embrace of Vergara).

In 1840, María Cristina, aware of her weakness, tried to reach an agreement with Espartero, but he sided with the progressives when the "revolution of 1840" broke out in Madrid on 1 September. María Cristina was then forced to leave Spain and leave the regency in Espartero's hands on 12 October 1840.

During Espartero's regency, the general did not know how to surround himself with the liberal spirit that had brought him to power, and preferred to entrust the most important and transcendental matters to like-minded military officers, known as Ayacuchos because of the false belief that Espartero had been at the Battle of Ayacucho . In fact, General Espartero was accused of exercising the Regency in the form of a dictatorship.

For their part, the conservatives represented by Leopoldo O'Donnell and Narváez did not cease their pronouncements. In 1843 the political deterioration worsened and even the liberals who had supported him three years earlier were conspiring against him. On 11 June 1843 the revolt of the moderates was also backed by Espartero's trusted men, such as Joaquín María López and Salustiano Olózaga , which forced the general to abandon power and go into exile in London.

With the fall of Espartero, the political and military class as a whole came to the conviction that a new regency should not be called for, but that the Queen's majority should be recognised, despite the fact that Isabella was only twelve years old. Thus began the effective reign of Isabella II (1843–1868), which was a complex period, not without its ups and downs, which marked the rest of the political situation of the 19th century and part of the 20th century in Spain. [1] [2]

The proclamation of the coming of age of Isabella II and the "Olózaga incident" produced a political vacuum. The "radical" progressive Joaquín María López was restored by the Cortes to the post of Head of Government on 23 July, and to do away with the Senate, where the "Esparteristas" had a majority, he dissolved it and called elections to renew it completely – in violation of Article 19 of the 1837 Constitution, which only allowed it to be renewed by thirds. He also appointed the City Council and the Diputación de Madrid – which was also a violation of the Constitution- to prevent the "Spartacists" from taking over both institutions in an election —López justified it as follows: "when fighting for existence, the principle of conservation is the one that stands out above all: one does what one does with the sick person who is amputated so that he may live ". [1]

In September 1843 elections to the Cortes were held in which progressives and moderates stood in coalition in what was called a "parliamentary party", but the moderates won more seats than the progressives, who were also still divided between "temperates" and "radicals" and thus lacked a single leadership. The Cortes approved that Isabella II would be proclaimed of age in advance as soon as she reached the age of 13 the following month. On 10 November 1843 she swore in the Constitution of 1837 and then, in accordance with parliamentary custom, the government of José María López resigned. The task of forming a government was given to Salustiano de Olózaga, the leader of the "temperate" sector of progressivism. He was chosen by the queen because he had made an agreement with María Cristina on his return from exile. [2]

The first setback suffered by the new government was that its candidate to preside over the Congress of Deputies, the former Prime Minister Joaquín María López, was defeated by the Moderate Party candidate Pedro José Pidal, who not only received the votes of his party but also those of the "radical" sector of the progressives headed at the time by Pascual Madoz and Fermín Caballero, who were joined by the "temperate" Manuel Cortina. When the second difficulty arose, to push through the Law on Town Councils, Olózaga appealed to the queen to dissolve the Cortes and call new elections that would provide him with a supportive House, instead of resigning because he had lost the confidence of the Cortes. It was then that the "Olózaga incident" occurred, which shook political life as the president of the government was accused by the moderates of having forced the queen to sign the decrees of dissolution and calling of the Cortes. Olózaga, despite proclaiming his innocence, had no choice but to resign and the new president was the moderate Luis González Bravo, who called elections for January 1844 with the agreement of the progressives, despite the fact that the government had just come to power and had reinstated the 1840 Law on Town Councils – which had given rise to the progressive "revolution of 1840" that ended with the regency of María Cristina de Borbón and the assumption of power by General Espartero. [2]

As for the "Olózaga incident", the new President of the Council of Ministers , González Bravo, who had taken office on 1 December, proposed discussing it in the Chamber. During the sessions Olózaga demonstrated the falsity of the accusations, but the parliamentary majority enjoyed by the moderates after the elections enabled him to win the vote, and Olózaga left for England, not so much because of a banishment that had not been ordered, but out of fear for his own life, which was threatened in Madrid. In some parts of the country, the political direction the Kingdom was taking was viewed with suspicion, which led to some rebellions, such as the Boné Rebellion led by Pantaleón Boné, who took control of the city of Alicante for more than 40 days with the intention of extending his revolution to other cities.

González Bravo carried out a kind of "civil dictatorship", which would last 6 months, and during which he restored the Law of Town Councils to put an end to the Juntas, and put an end to the National Militia by creating the Civil Guard. [3]

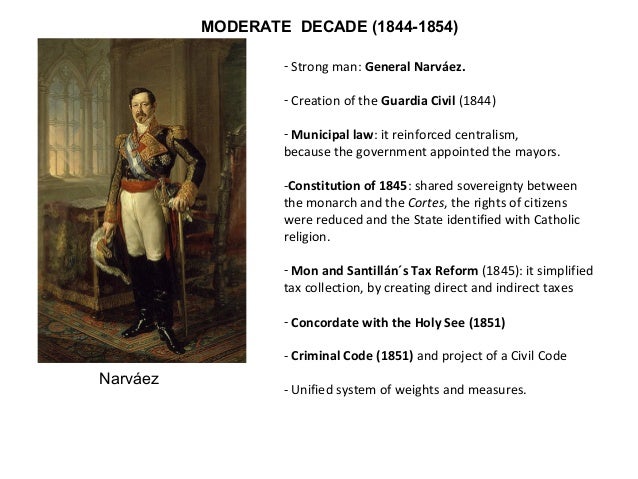

The January 1844 elections were won by the moderates, which provoked progressive uprisings in several provinces in February and March that denounced the government's "influence" on the outcome of the elections. Thus the progressive leaders Cortina, Madoz and Caballero were imprisoned for six months -Olózaga was not arrested because he was in Lisbon and Joaquín María López remained in hiding until his companions were released from prison-. In May General Ramón María Narváez, the true leader of the Moderate Party, assumed the presidency of the government, inaugurating the so-called moderate decade (1844–1854). [3]

After the fall of Espartero and the proclamation of Isabella's majority, a series of moderate governments began, supported by the Crown. The first measure taken by the moderates in power was to prevent progressive uprisings, for which they disbanded the National Militia and re-established the Law of Town Councils to better control local governments from the central government, which prevented the creation of Juntas. When her reign began, the Queen was only 13 years old and had no experience of government, so she was greatly influenced by the people around her.

In the spring of 1844 the country was considered to have been pacified, which meant that the civil dictatorship of González Bravo came to an end and new elections were called, in which Narváez

won. This was a complicated situation for him, as he had not shown great political skills. He ran a very authoritarian government, treating the ministers as his subordinates in the army. Narváez took a step forward in political reforms, going as far as the construction of a centralised state and fiscal reform. His ministerial team included Alejandro Mon , Minister of Finance, in charge of tax reform; Pedro José Pidal , Minister of the Interior, in charge of creating the centralised state and the concordat with the Church in 1851; and Francisco Martínez de la Rosa , Minister of State and creator of the policy of the just average.

With the presidency of the leader of the Moderate Party, General Narváez, who took office on 4 May 1844, the Moderate Decade began, so called because during those ten years the Moderate Party held exclusive power thanks to the support of the Crown, without the progressives having the slightest chance of gaining access to government.

With the Moderate Party firmly in government, 1845 was a crucial year for Spanish liberalism, as it was a crossroads at which the Moderate Party took stock of its achievements and failures since the Liberal Revolution. According to the government, it was time to see what could be maintained and what had to be changed. According to Narváez, if the revolutionary cycle came to an end in 1845, a number of problems would have to be addressed, such as the Carlists, unhappy at the failure to fulfil the agreement with Espartero; the situation of the Church, which had lost much of its heritage and above all its influence; and political problems, known as "constitutional instability", because two constitutions had been drawn up in less than five years. The solution found by the moderates was to draw up a new constitution, that of 1845.

Several drafts of a new Constitution were presented, including that of the Marquis of Maluma, which followed the line of a charter that gave all power to the Crown, and was therefore rejected outright. The progressives could not oppose Narváez because they had no presence in the Cortes, so the doctrinaire liberal model was established, which would establish a constitutional monarchy with sovereignty shared between the Crown and the Cortes.

In terms of the declaration of rights, the 1845 Constitution was notable for its laws on printing and religion. There was no prior censorship of printing, but special courts were created to try crimes of insult against the government or the Crown. With regard to religion, the freedom of worship of 1837 was rejected, although it did not reach the intolerance of the Cadiz Constitution of 1812. In 1845 Spain became a confessional state and the subsidy for worship and the clergy was re-established, as well as favouring the presence of the Church in education, which served as the first step towards reconciliation between Church and State, which would come in 1851 with the Concordat .

With regard to the organisation of the powers of the State, the 1845 Constitution established a bicameral model, Senate and Congress, renewed every five years and whose representatives were elected by means of the law of single-member districts (in each district there was only one winner) to achieve very stable parliamentary majorities. In addition, the rents to be elected (12,000 reals) and to vote (400 reals) are established. In 1846 only 0.8% of the population, almost 100,000 people, voted.

During this period of complete moderate rule, the latter tried to reverse the liberal advances of the previous stages, imposing a new municipal law (8 January 1845) with direct census suffrage , reinforcing centralism and approving a new constitution, that of 1845, which returned to the model of shared sovereignty between the King and the Cortes and reinforced the powers of the Crown. On the legislative level, various Organic laws were passed that accentuated the centralisation of public administration by controlling the political power of the Town councils and universities, in a clear attempt to limit their powers as they were heavily influenced by the liberals.

The division of the Moderate Party soon emerged, which contributed to the political instability that manifested itself in the continuous changes in the presidency of the government, beginning with the dismissal of Narváez on 11 February 1846, associated with the conflictive marriage that was arranged for the Queen. In fact, that year she was to marry Francisco de Asís de Borbón , her cousin, on 10 October. Earlier, the Queen's mother, the former Regent Maria Cristina , had hatched a marriage plan to marry her daughter to the heir to the French crown . Such plans aroused the suspicions of England, which at all costs wanted the Treaty of Utrecht to be respected and to prevent the two nations from being united under a single king. After the Accords of Europe, the number of candidates for Elizabeth was limited to just over six, from which Francis of Assisi was finally chosen.

Francisco Javier de Istúriz's government managed to hold on until 28 January 1847, when a struggle for control of the Cortes with Mendizábal and Olózaga, who had returned from exile after the Queen's personal authorisation, forced him to resign. From January to October of that year three governments succeeded one another without direction while the Carlists continued to stir up trouble and some liberal émigrés returned from exile.

On 4 October Narváez was reappointed President, who appointed the conservative Bravo Murillo as his right-hand man and Minister of Public Works. The new government was stable in principle until the Revolution of 1848, which swept through Europe, led by the workers' movement and the more liberal bourgeoisie, provoked insurrections in the interior of Spain, which were harshly repressed; in addition, diplomatic relations with Great Britain were broken off, as it was considered to be a participant in and instigator of the Carlist movements in the so-called Matiners' War. Narváez acted as a true dictator, confronting the Queen, the King consort, the liberals and the absolutists. The confrontation lasted until 10 January 1851, when he was forced to resign and was replaced by Bravo Murillo.

Once in power, Bravo Murillo tried to appease the confrontation with the Holy See as a result of the disentailment processes carried out by Mendizábal in the previous period by signing a Concordat in 1851 with Pope Pius IX, the second in the history of Spain, which, in short, established a policy of protection for the assets of the Catholic Church against possible new disentailment processes, especially civil ones; The sale of those still in the hands of the State was halted and the Church received financial compensation. In its first article, the Concordat established:

"La religión católica, apostólica,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reign_of_Isabella_II_of_Spain

https://www.facebook.com/isabellareignusa/

3d Porn Comic Zz2tommy The Zoo

Czech Czech Home Orgy 6 Part 4

Real Swingers

Reign of Isabella II of Spain - Wikipedia

Isabella Reign USA - Home | Facebook

Isabella I | Biography, Reign, & Facts | Britannica

Isabella Reign - YouTube

Isabela Reign Profiles | Facebook

Isabella I of Castile - Wikipedia

Isabella and Ferdinand | World History

Isabella Reign USA (@isabellareignusa) • Instagram photos ...

Isabelle Manich Reign Profiles | Facebook

Catholic Monarchs of Spain - Wikipedia

Isabella Reign