Is the Cloud Secure Enough?

More and more organisations are moving their data to the cloud. I get the opportunity to work with a lot of different companies, and one of the things I've noticed very consistently is that organisations are more likely to be breached after they go to the cloud than when there are still on-premises. That leads me to the obvious question: is the cloud secure enough?

When we say "the cloud", it's important to realise that there are lots of different clouds and they're not all created equal. There's a common meme you've probably seen: "there is no cloud, it's just someone else's computer". Now that's obviously a crass simplification.

If you take Amazon Web Services and compare it to your laptop, I'm sure you'll notice one or two differences there. But it does have a point. If your data lives in the cloud, then ultimately it does live on someone else's computer. When we're talking about the security of your data then the way that other person manages your computer really does matter.

One of the benefits of cloud is you don't need to know how it all works. Which means you can spend your time worrying about something more important. One of the downsides of cloud is you don't know how it all works.

So if it was really bad behind the scenes, you wouldn't necessarily know it. I've seen some seriously shoddy kit, operated by people with very little idea what they're doing, masquerading as a public cloud service. It varies from that, all the way to the sophisticated heights of Microsoft and Amazon; and everything in between.

Just because a cloud provider is very small compared to Amazon doesn't mean they're not very good, and this is where it gets difficult.

So how do you know that they're taking the security of your data seriously? One of the things I recommend is quite simple. Ask them. Ask them how they're protecting your data and ask for evidence. Here's the thing: if a company's taking security seriously, they'll be very happy to talk to you about it. You're literally giving them the opportunity to tell you how wonderful they are.

If, on the other hand, a company doesn't want to talk about it. If they say that they're so secure that talking about the security would somehow compromise it, then that is an immediate red flag. What they probably mean is that if people knew how bad it was, they've be in serious trouble. Avoid.

Let's get back to that matter of security. If you're using one of the really big providers like Microsoft or Amazon or Google, then you can be fairly sure they're taking security seriously. They kind of have to. They're too big a target not to. If their systems were breached, that would make global headlines and cause massive reputational damage. Their datacenters are physically secured using perimeter boundaries, manned checkpoints, vehicle traps, motion sensors, video surveillance, infrared, biometrics... You name it, they've got it.

Let's take a look at Office 365 as an example. Microsoft maintains strict separation between the people who manage the software and the people who manage the hardware. That means the people who can access the kit your data lives on have no idea where any of the data actually lives, and the people who do know where the data lives have no way to access the kit. That means if someone was trying to physically steal your data, they don't have both pieces of the puzzle; and even if they did, the whole thing's encrypted anyway. On top of that you've got sophisticated access control and monitoring.

An administrator can't just log on to your server - they have to make a request, and they have to say exactly what they're going to do, when they're going to do it, and what systems they need to do it on. If that request is approved, a temporary account is provisioned that gives them just the access they need, at just the time they said, on just the systems they said; an all of that access is fed into a monitoring system that uses machine learning to look for anomalous behaviour. The admins can only run a certain set of preapproved tools. Even if they somehow managed to get something else onto the server, it won't actually run because it has to be specifically whitelisted or it's blocked at the operating system level.

As a final precaution, every single server is rebuilt every two weeks on a rolling basis. That's partly a precaution in case something nasty did slip in, despite all of the safeguards; but it's also because patching is a pain in the backside. When you're offering at hyperscale and you've got all of that automation, it's just simply easier to rebuild the systems on the latest version than it is to patch the software in-place.

In order to keep themselves ahead of the bad guys, Microsoft conduct red team versus blue team wargames. They employ a team of hackers to try and break to their systems, and a team of security professionals to try and stop them. This helps them find weaknesses early, as well as helping them perfect their defences. In theory you can do all of this yourself; and Microsoft being Microsoft, will happily sell you a lot of the tools you need to do it.

But, let's be realistic. Doing this to the same degree of rigour as Microsoft or Amazon is going to be cost-prohibitive for most organisations. Well that all sounds really good! Yay for cloud, right? But hang on.

If the cloud is so secure, then how come people are more likely to be breached when they use it? Well, so far I've only talked about half of the equation. The cloud operates on a shared security model. That means the vendor is responsible for some of it, and you're responsible for some of it.

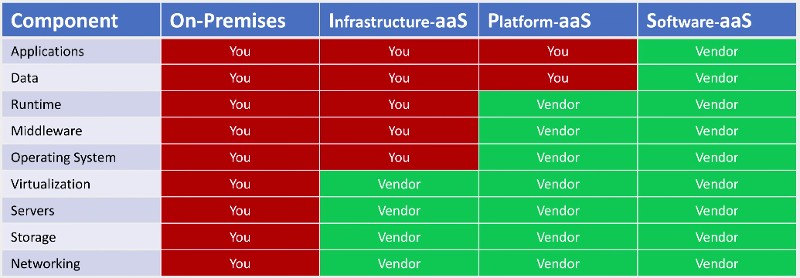

If you think of securing the cloud like building a castle, where the vendor builds the walls and you build the gate; there's no point to vendor making 30 foot thick walls if you're going hang a curtain. I find this table helpful to visualise it.

I can't take credit for it - I've copied this off a Microsoft website. It's not intended as a security diagram, rather it's intended to show where the division of responsibilities lies for different types of cloud services.

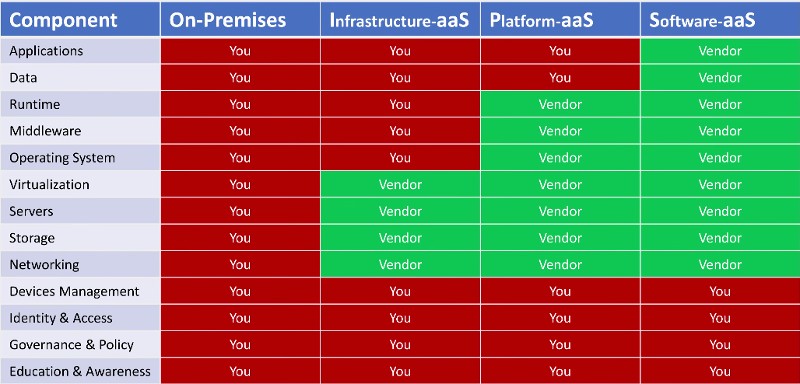

Everything in red, you're responsible for; and everything in green, the vendor is responsible for. This is useful to explain the broad differences between the different types of cloud services, but it focuses on the differences, and there are a whole bunch of responsibilities that aren't on there because they don't really change. Let me add a few in.

Now these are important, because regardless of which type of cloud service you're using, these all fall on you; and all of these are directly impacting the security of your data.

This area that wasn't on the original table, this is where the vast majority of real-world breaches are happening. This is the weak spot. You might be looking at that thinking "But there's nothing new here. I still have to manage that on-premises. Managing my devices my identities - that's not cloud specific?". No, it's not. In fact there's nothing new here. Moving to cloud doesn't change those responsibilities, but it does change the stakes.

The simple and uncomfortable truth is that a lot of organisations are doing a poor job in these areas. The recurring argument I hear is "I've been operating this way for 15 years and I've not had a breach. Why should I invest in security now?". With any risk, security or otherwise, there's an element of luck involved. The less you choose to manage risk, the more you're reliant on luck.

For a lot of organisations, the reason they haven't been breached yet is either because they've been lucky, or they have been breached and they just haven't realised. Their defences haven't stood the test of time because they're robust enough. Their defences have stood because they've never been tested.

When you move to the cloud your luck changes. You no longer have the relative anonymity of the server at Bob and Jane's Widget Factory. You're now Office 365 - one of the largest and most well-known computer systems on the planet. That means you have a massive target painted on you, and your defences are much more likely to be tested.

Let's look at a common example of how this works. A huge number of breaches originate in a phishing email. This is an email that looks like a sort of email you'd expect normally receive, and it usually links off to a website with a login; but when you log into that website, it takes username and password and sends them off the attacker.

If you're going to target Bob and Jane's Widget Factory with a phishing campaign, you need to figure out what their emails typically look like. Who sends them? What sort of language do they use? What is the branding on those emails? And once you've done that, you need to make your login page look like a login page their users would expect to see. Again, with all the branding of one of their systems. And once you've got their credentials, you need to figure out how to use them. What systems do they have? How are they accessible? How can you log in and extract the data? That's quite a bit of effort.

If you were specifically out to target Bob and Jane's Widget Factory, you'll be willing to put that effort; in but most attackers are just looking for an easy score, and individually attacking and researching lots of individual companies is not an easy score. For an easy score you want to send an email to the maximum number of people, with a minimum amount of effort, that means targeting the biggest provider possible. One of the big global ones like Office 365 or G Suite.

While Bob and Jane are still on-premises an Office 365 branded email is going to look a little bit out of place; and if it takes them to a login screen branded as Office 365 that they've never seen before, then that's going to arouse suspicion. Once they've moved to Office 365 on the other hand, that email's going to look just like a lot of the emails they receive every single day; and that login page is going to look like the same login page they use every single day. At that point they're much more likely to trust it and click the button. Once they click the button, it's Office 365, so the attacker knows exactly how to use his credentials to extract data.

This sort of thing is where we're seeing cloud services being breached all the time. The weakness is the people using it. The vulnerability is the familiarity and increased likelihood of being targeted.

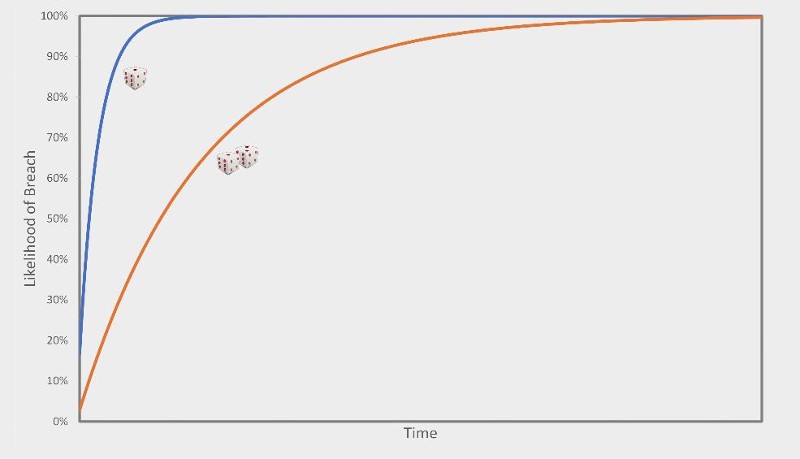

So are you better off staying on-premises, then? Well, despite what the salesman may have told you, there's nothing wrong with deployed on-premises services if that happens to be the best solution for you; but it's not addressing the problem here. Think of it like a game of dice. When you're in the cloud, you wake up every morning and you roll a die. If you roll a six, your data gets stolen. I'm not actually saying there's a one in six chance every day, it's just an analogy, bear with me. But going by that analogy, if you're on-premises maybe it's like you roll two dice, and you only lose your data if you roll double sixes. So that's better, right? There's less chance of being breached? No.

There's less chance of being breached on your next roll, but over time both scenarios trend towards a 100% probability of you being breached. The answer isn't to add more dice. The answer is to stop rolling, and that means taking your security responsibilities seriously.

The cloud offers plenty of opportunity to develop a strong security posture. By taking advantage of hyperscale services by global industry leaders, you can achieve a level of security that would be cost-prohibitive to do yourself. But you have to actually do it. If you take advantage what the cloud has to offer, you can be more secure than ever before; but if you just bring bad practice to the cloud, it is more likely to punish you.

One of the best ways to defend against the sort of attack I've mentioned is to use multi-factor authentication. Microsoft stats show it blocks 99.9 percent of account compromise attacks.