Interview with Martin Lee : The Last Knight Defending One Country Two Systems

Translated by Guardians of Hong Kongby Amber Lin, a Taiwanese journalist and a Pulitzer Center’s 2019-2020 Persephone Miel fellow

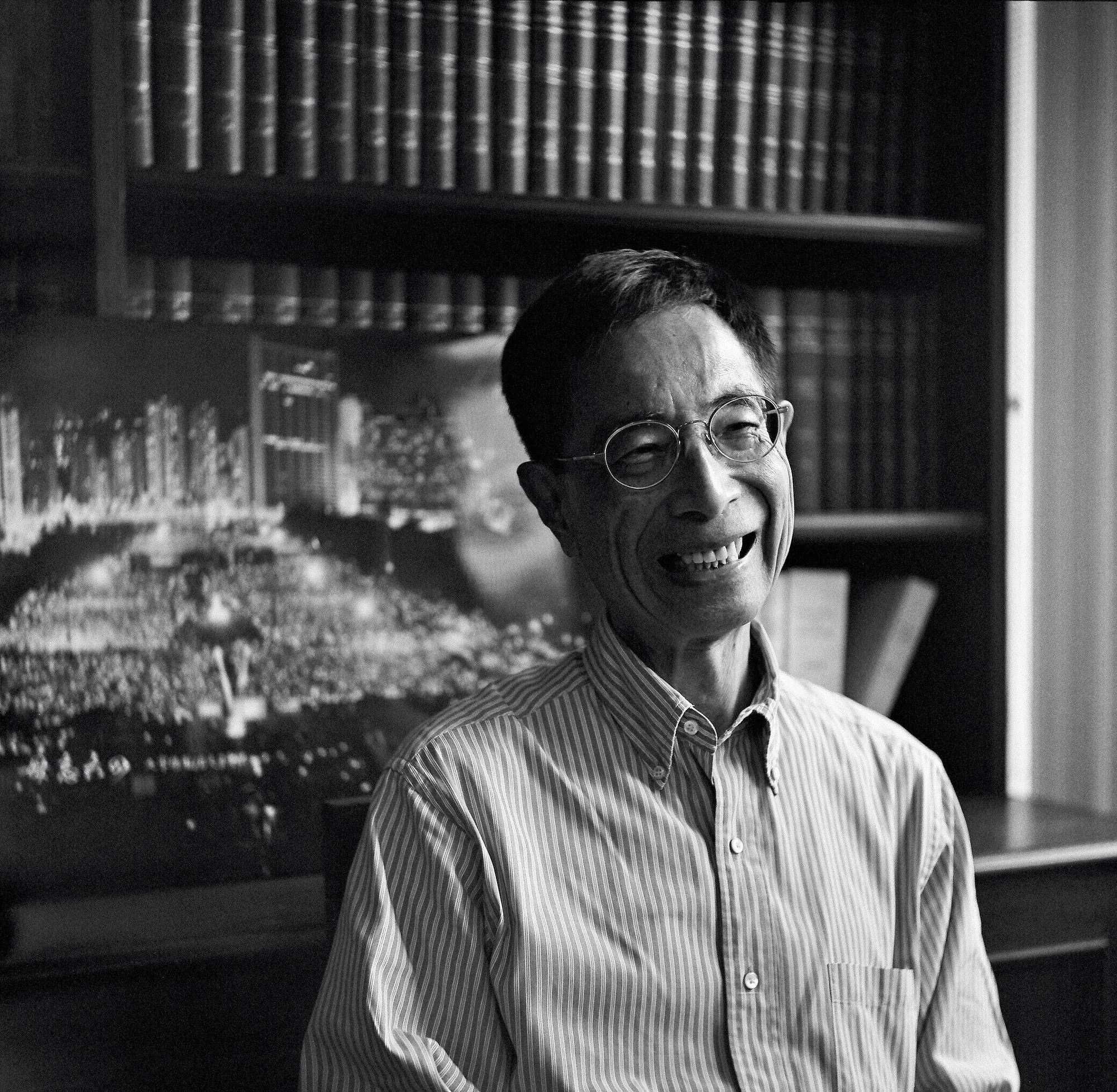

Editor’s note: Martin Lee, the founder of Democratic Party and an experienced barrister who was on the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee, was arrested in late April 2020. Lee still firmly believes in "One Country Two Systems" even though a majority of Hong Kongers do not feel the same way. In the interview, he explains some of his past decisions and discusses his thoughts and feelings about the future of Hong Kong.

************************************

Martin Lee is like the last knight in the Middle Ages holding two contracts, the Sino-British Joint Declaration as the shield and the Basic Law as the sword. He insists on demanding Beijing to stick to her promises with the rules of honour, faith and morality.

He was part of the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee, the founder of the Democratic Party and an experienced barrister. Having been part of Hong Kong’s democratic movement, Lee still firmly believes that “One Country Two Systems” is the only answer for Hong Kong at this moment, despite many claiming that “One Country Two Systems” no longer works. This is the last asset inherited for the protection of Hong Kongers’ interests. Will Hong Kong’s father of democracy see his faith and belief manifest in reality?

“... Whoever becomes the master of a city accustomed to live in freedom and does not destroy it, may reckon on being destroyed by it. Should it rebel, it can always hide behind the name of liberty and its ancient laws, which no length of time, nor any benefit conferred will ever make it forget; and do what you will, and take what care you may, unless the inhabitants are scattered and dispersed, this name, and the old order of things, will never cease to be remembered...”

― Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince

It was the beginning of 2000, Lee received a call from the White House. A member of Bill Clinton’s cabinet told him that Clinton had read his article in South China Morning Post, in which Lee stated his stance supporting the United States to help China enter into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and build the status of permanent normal trade relations (PNTR). In the article, Lee claimed that the West should let China join the global institution. He expressed his willingness to help Clinton persuade a House of Representatives which was strongly opposed to it. Leading the discussions at the time was Nancy Pelosi, the current Democratic House Leader and also a friend of Lee.

His trip to the White House in May went well. Lee told Pelosi, who insisted on reviewing China’s human rights condition every year, that shutting the door to China cannot solve the problem; the best way to prompt China to make progress in civilization is to encourage China to comply with international agreements; and thus respect the rule of law and human rights via offering economic incentives like trade agreements.

On another day, he persuaded Clinton the same way and reminded the US President that the US had to closely monitor whether China conformed to every regulation because the bill could lead to distinctly different outcomes: either his efforts would pay off and China would learn how to respect the rule of law and human rights; or they would prolong the reign of tyrants.

It was predicted that the bill would only pass by a margin. In the end, this historically important bill, the “U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000” was passed in the House by Representatives with majority votes. According to the Act, once China joined WTO, the US would grant China PNTR. The most fierce battle in the US Houses of Congress in recent history ended the 10-year debate on U.S.-China diplomatic policies. “The Pandas”, those in support of maintaining a relationship with China, won. Economic and trade became the main focus of the Sino-American relation after the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident.

This sudden recollection of this past tale by Lee now seems prescient. In early March 2020, COVID-19 spread uncontrollably in Europe and the US —this was the moment when the international community finally realised that the World Health Organisation (WHO) may already be in the tight grip of China, and this may be one of the causes for the uncontrollable spread of this pandemic. The western world is now bearing the consequence of letting China do anything she wants. Meanwhile, China’s vigorous international propaganda tried to mislead the world that US is the origin of the virus. At the same time, China has also tightened its grip on Hong Kong when every other country is busy with its own business.

On the morning of 18 April, the Hong Kong Police made a sweeping arrest of 15 moderate democrats. In the week before, Beijing kept hinting at its tightening grip on Hong Kong: mentioning LegCo members can be disqualified; spreading news indicating the challenges faced by the judicial system in Hong Kong; talked of the imminent implementation of Article 23; making a new interpretation of Article 22; and changing principal officials of the Hong Kong Government.

Fear itself is not the most harmful, but this mass arrest symbolises something much greater than the arrest itself. Among the arrested, Lee, as a popular democrat, was the one gaining the most attention.

The almost 82 year-old experienced and revered barrister was a member of the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee, the Founder of the Democratic Party and a legislator for 23 years. Since the age of 47, when he first participated in Hong Kong’s democratic movement, he has defended many activists. Still, without experience as a political prisoner he could not become a symbol of morality like Mandela. The arrest on April 18 was like the last piece of the puzzle for this father of democracy in Hong Kong. Today, he no longer feels guilty but is relieved for finally being able to walk with youths on the path to democracy.

Lee had not been in the frontline for years and he longs to contribute to Hong Kong again—a few years ago, politicians of the younger generation like Joshua Wong and Nathan Law already took his position in the international battlefield. They quickly leveraged Lee’s strong connections with the West and spoke at European and US parliaments, overseas seminars and overseas media channels. They might be doing an even better job than Lee—the seamless passing of a legacy from one generation to the next is particularly obvious in the history of Taiwan and Hong Kong democratic movements.

“Even though I have witnessed consequences I did not want to see, I still want to give it a go.”

While societies in Hong Kong and overseas are shocked at the arrest of Lee, many are guessing Beijing’s even more ambitious intentions behind. Trump’s decision to halt funding to WHO re-ignited the decade-long debate in the West: should we intervene or distance ourselves from China?

The difference now from the year 2000 is that the liberals in the West are no longer the top dogs -- the fantasy about changing China through dialogues and interactions proved to be a pipe dream. In 2018, Mike Pence, the Vice President of the US, already reflected upon this in one of his speeches that when the Soviet Union dissolved, the US was so optimistic—they believed that if they opened the door for China, and got China into WHO, China would progress towards democracy, but this hope was shattered.

Does Lee regret facilitating the establishment of the “U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000”? “At that time I thought China needed encouragement. They should be given learning opportunities. I also warned President Clinton. Unfortunately, the US did not strictly monitor China afterwards. They thought when China became rich with a developing middle class, China would become democratic.” Lee continued, “Actually at that time, even if Nancy (Pelosi) had won (in the congressional debate), China would still get into WTO, it would have been only a few years delayed. Even though I feared the consequences, I still hoped to give it a try.”

His wish deep down was that China would learn to comply with international agreements, and hence, would also comply with the Sino-British Joint Declaration. Lee, a secondary school teacher when he was young, with his patience and kindness has always led him to have a naively positive attitude towards humanity.

At the time, everyone was attracted to the huge market with a population of 1.3 billion and simply accepted Beijing’s propaganda. China was telling the world that they were rising peacefully by displaying the Chinese character “harmony” at the 2008 Olympics despite the fact that they were suppressing human rights even more vigorously those years. The West chose to turn a blind eye to the suppression in exchange for the tremendous business opportunities.

“Beijing always accused me of being a traitor, but I always do everything in the best interest of Hong Kong. This is why I was willing to speak on behalf of China.” Lee asked, “Is this traitorous?”

“I was not a supporter of a democratic repatriation. I had no choice but to accept One Country Two Systems.”

On 1 July 1997, the handover day of the sovereignty of Hong Kong to China, Lee published The 1 July Declaration: The Return of Hong Kong is not only about returning the land.

“The Democratic Party supports Hong Kong’s return to our mother country in a democratic way. We firmly believe that democracy was equally important to both Hong Kong and China…….One Country Two Systems is an admirable idea. The success of One Country Two Systems requires the leaders of China and Hong Kong people to build a democratic system together……We firmly believe that one day, Hong Kong will build a genuine One Country Two Systems and exercise an truly high degree of autonomy on the basis of democracy. China will also become a great country with the rights of nationals protected by robust laws!” If you take a look at what he wrote in 1997, you will find him a patriot rather than a traitor.

The arrests of pro-democratic politicians on 18 April put an end to the 30-year fantasy of Hong Kong’s “democratic” return to China. On the list of the arrested, Lee Cheuk-yan and Leung Kwok-hung, both seen as “Democratic Repatriation Supporters” and “Greater Chinese Nationalists”. Throughout the second half of 2019, the sacrifices from the violent protests in Hong Kong were done for fellow comrades in Hong Kong and not for fellow mainland Chinese in the north.

Yet, Lee does not see himself as “a supporter of democratic repatriation.” “I do not agree with a democratic repatriation. I was forced to accept One Country Two Systems,” he reiterated.

Compared to Szeto Wah and Leung Kwok-hung, there is actually not much “Chineseness” in Martin Lee. He is more like a British middle-class conservative gentleman, rather than a Chinese scholar.

He was never an anti-colonialist who severely criticized Britain. When the United Kingdom and China held negotiations in 1980s, Lee even wrote a letter with others proposing that after the return of Hong Kong to China, Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories should continue to be leased to the UK, to avoid conflicts between the two systems and to ensure the continued prosperity of Hong Kong.

Yet, Deng Xiaoping did not accept this proposal and raised the concept of One Country Two Systems, emphasising that China would not intervene with Hong Kong affairs. At that time, the Communist Party of China (CCP) also started to work harder to persuade the student unions of the universities in Hong Kong. Later, the student union of the University of Hong Kong wrote to Zhao Ziyang, who gave them a clear reply—democracy and One Country Two Systems can merge. The arguments in support of a democratic repatriation thus gained legitimacy.

“This was a small detail in history but of high importance,” Lee insists on a meticulous reconstruction of public opinions at the time because history can only be fairly judged in truth. “At that time, I think that the bottom line of One Country Two Systems is the absence of interference from Beijing. Later, Zhao promised that there would be democracy, so then it might work. I had no other choice. What I could do was to ensure the system works.”

Seeing that the return of Hong Kong to China was imminent and that Deng Xiaoping wanted Hong Kong to be the role model of One Country Two Systems for Taiwan, Lee, at the age of 47, decided to join the drafting of the Basic Law as a legal expert. Turning the Sino-British Joint Declaration into precise laws was how he could contribute for Hong Kongers.

The life journey of a “Chinese-Hong Konger”, a patriot and traitor

To Lee, there is no conflict between being a Chinese and fighting for Hong Kongers his whole life. It is natural for him. He dislikes how youth nowadays think the Hong Konger identity and Chinese identity are mutually exclusive. He identifies as a Chinese person and is seen as a traitor in the eyes of Beijing because of his pursuit of democracy—people like Lee take it as the irrefutable destiny of being “a pro-democratic Chinese-Hong Konger” struggling between China and the UK.

Lee is known as Martin overseas and in Hong Kong, which also shows his mixed Chinese-British cultural background. His life journey and the choices he made were a common fate shared by many other Hong Kongers in his generation who lived through the wars.

Lee was born in Guangdong Province, China in 1938. He experienced the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, the Second World War, the Chinese Civil War. His father, Lee Yin-wo, was a Kuomintang (KMT) general who fought the Japanese. Meanwhile, Lee’s mother took her four kids and fled the country. After Chiang Kai-shek lost the war In 1949, Lee Yin-wo, as a member of the Control Yuan committee at that time and also a classmate of Zhou Enlai (in Lyons, France) did not move to Taiwan because he could not agree with the corruption of KMT.

Meanwhile, he did not trust the CCP either because they ruined traditional Chinese family values. He believed his children would get better education and gain more freedom in Hong Kong under the British rule. So he chose to move the whole family to Hong Kong. However, he and his wife were also prepared to die in case the CCP came after them, so that the children may survive.

After the CCP established the People’s Republic of China, Zhou Enlai became the most trusted subordinate and kept sending secret messengers to Hong Kong to persuade Lee Yin-wo to return to Beijing to help the CCP. Lee Yin-wo moved home every time his location was exposed.

Martin Lee could not stop talking as he recalled his childhood memories. He is not fluent in Mandarin; his mother tongues are English and Cantonese. He could only say 4 English words when he arrived in Hong Kong at the age of 10. In 1956, he was admitted to the Department of English Literature at the University of Hong Kong and became a secondary school teacher after graduating from university in 1960. With his passion for debate, he went to London to study a degree in law in 1963. Though he only spent 3 years in the UK, Lee was able to express himself as eloquently as other Western scholars. In 1966, just one year before the 1967 Hong Kong Riots, he went back to Hong Kong and became a barrister.

Refusing to be ruled by the CCP again—sprout of democracy in Hong Kong facing a deadline set in 1997

Hong Kong was not a city born to pursue freedom. Before the dissolution of the British Empire from the wave of decolonisation, the empire had to confront the robust resistance from different races in its far-east colonies, such as India, Myanmar and Malaysia. Surprisingly, Hong Kong, as a refugee society, was the most stable apolitical free port.

The refugees who escaped China in 1950s and 60s because of the civil war or the Cultural Revolution worked hard to make a living in this temporary shelter. Their final destination was the free and rich America. At that time, Hong Kong was “a borrowed place with borrowed time” and locals were treated as second-tier citizens by the British. However, the locals never wanted to be the owner of this place.

In late 1960s, refugees started to perceive Hong Kong as their home, claiming themselves as the first generation of Hong Kongers. The underground political parties in Hong Kong were under the influence of the Cultural Revolution and anti-colonialism in 1967. With riots plotted by the CCP in 1967, disgruntled locals vented their dissatisfaction towards the British colonial government. At the same time, it also made Hong Kongers wary of the CCP.

After the 1967 Riots, the British government realised that the most efficient way to manage this far-east colony was not sending an army to suppress, but to win the locals’ hearts. Taking this free port as a gold mine without the intention to assimilate Hong Kong people, the colonial government invited revered local figures from different sectors into the establishment, put forward various reforms and cracked down on corruption. The last governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, even tried to introduce a democratic system in Hong Kong.

“(In the 1970s and 80s,) Hong Kongers were happy because opportunities were everywhere as long as you were willing to work hard. It was easy to be successful,” Lee recalled the pleasant memories delightfully. Different from Leung Kwok-hung whose teammates in protests were heavily beaten up by the police, Lee was not really dissatisfied with the colonial government, like most Hong Kongers with low political awareness at that time. The seed of democracy did not sprout until the 1980s when Hong Kongers faced the problems brought on by the handover when they realised that they did not want to be ruled by the CCP.

When ruled by an empire adopting a democratic system, Hong Kongers only cared about money but not politics at all. Yet, after the handover to China, the Spirit of Lion Rock was gradually turned into one in pursuit of democracy and justice rather than pure commercialism.

In the golden age of China-Hong Kong relationship, Lee participated in drafting the Basic Law

The negotiations between China and the UK in the 1980s took place when Hong Kong had the strongest bargaining power since Hong Kong was declared as a free port in 1841.

In 1980, Lee became the chairman of the Hong Kong Bar Association and the negotiations began in 1982. Everyone was worried while Hong Kong dollars were depreciating. All of his lawyer friends had a flight ticket and two passports with them all the time—a Hong Kong passport and a Dominican passport—so they could go to Canada or the US. He once considered working in California but after serious considerations, he realised he did not want to leave Hong Kong. He felt that Hong Kong needed his professional skills at that time so he stayed.

To leave a legacy from a prosperous empire, the UK granted Hong Kong elections before they left. On the other hand, China needed Hong Kong as a door to the international system. To assuage Hong Kongers’ fear and to reassure financial giants and overseas enterprises, Deng promised One Country Two Systems, a high degree of autonomy for 50 years and universal suffrage for election of the Chief Executive and the Legislative Council 10 years after the handover.

“At that time, China kept persuading us that only two things would change after the return: the flag and the governor,“ Lee recalled the CCP’s strategy and they successfully convinced Hong Kongers as well as London and the international communities that China was making progress and One Country Two Systems was a great experiment of political systems in the history of mankind.

In 1984, after the release of the Sino-British Joint Declaration with Deng’s promises written in black and white, Hong Kongers felt relieved and went straight into the drafting of the Basic Law. Lee was invited to be a member of the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee in 1985. In the same year, the UK granted the first indirect election for Legislative Council—Lee decided to step into politics and was elected to be a legislator of the Legal functional constituency.

Lee was nostalgic about the golden age of the China-Hong Kong relationship which only lasted 4 years from 1985 until the Tiananmen Crackdown in 1989, the incident that also determined the destiny of Hong Kong after the handover.

Historical details pop up incessantly in his mind

He remembers during the first gala dinner with other Drafting Committee members in Beijing, the deceased Chinese legal expert Wu Jian-fan said to him, “I know that the Sino-British Joint Declaration is popular in Hong Kong. Let’s work together. If the Basic Law is completed but isn’t accepted by Hong Kongers like the Sino-British Joint Declaration, it means we have not fulfilled our duties.”

The Drafting Committee consisted of 59 members; among the 23 members from Hong Kong were legal professionals, the rich who wanted to build relationships with Beijing as well as popular figures like Jin Yong, Szeto Wah and Li Ka-shing etc. Some of the other 36 representatives from mainland China were top legal experts who studied in Germany, Russia, the UK and France etc. His most lasting memory is that among the committee, Szeto Wah, his partner, was the only one who was always in line with him in the meetings. His views were often disagreed with by other Hong Kong representatives who wanted to flatter Beijing. Yet, some of those representatives from China who opposed him in the meetings also asked him not to give up his views in private.

In his memory, these representatives from China longed to understand the differences between common law and civil law and sometimes interpreted for Lee who could not speak Mandarin fluently. They even taught Lee how to negotiate with the Central government so that Lee could get an idea of the Chinese way of thinking.

In 1982, when China started to negotiate with the UK, the first issue they came across was the legal system—while Hong Kong adopted common law, China adopted civil law. Complying with Deng’s principles, Chinese government officials unanimously agreed with keeping common law in Hong Kong when drafting the Basic Law. At that time, Beijing officials from Xinhua News Agency and scholars always consulted him about the legal systems.

Lu Ping, the main representative in charge of the handover of Hong Kong and Macau, and the Sino-British negotiation in the 1970s and 1980s, also the Director of Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office and the Secretary of the Drafting Committee in 1990s, also respected Lee’s opinion.

There were arguments but he still managed to achieve some breakthroughs. Lee even succeeded in persuading China to move the Court of Final Appeal from Beijing to Hong Kong. Lee has always been famous for giving straightforward criticism in public. Once, he used the phrase “saiing under false colours”—this irritated Lu Ping and he spoke to Lee in English gently, “You can criticize us but can you use milder language?” Lee apologised and corrected himself, after that their communication was smooth.

As it required Hong Kongers’ confidence in the handover, the Chinese government respected and appreciated this brilliant negotiator. Lee, aiming to defend the interest of Hong Kong wholeheartedly, was happy to be the bridge between China and Hong Kong. He had been busy with negotiations as a member of the Drafting Committee for 4 years, and had no time to make money as a barrister. The drafting of the Basic Law could have been completed in 2 or 3 months, but they spent 5 years drafting 3 versions instead—Beijing showed her sincerity.

“I never thought the drafting of a country’s constitution could be so open that they even allowed citizens to participate.” Lee cannot not forget how open-minded the Chinese government officials once were.

The relationship has not been the same after the 4 June 1989 Crackdown

Beijing’s attitude towards Hong Kong at that time was shockingly similar to that towards Taiwan now. China put forward plenty of measures beneficial to Taiwan in early 2018. In the speech on 40th anniversary of “An Open Letter to Our Fellow Brothers and Sisters in Taiwan” given in January 2019, President Xi officially invited political parties and civil organizations in Taiwan to discuss the “Proposal for One Country Two Systems in Taiwan”.

After the Anti-Extradition Bill Movement last year which showed that One Country Two Systems is merely sugar-coated poison, those who supported China to take Taiwan changed their lines, “The Republic of China is a country while Hong Kong is a special administrative region. Of course, the conditions of One Country Two Systems would be different. Everything can be discussed.”

Rational debate and persuasion no longer worked since the June 4 Crackdown in 1989. Hong Kongers and the international communities were shocked when Deng ordered a bloody massacre to suppress the protests at Tiananmen Square. Lee and Szeto Wah criticized this decision vehemently and quit the Drafting Committee. He was then labelled a traitor instead of the bridge and was banned from entering China again.

The nature of China-Hong Kong relations is indeed changing gradually. Even after 1989, Beijing still sent messengers to communicate with every democratic legislator. In 2004, Donald Tsang, then Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Government, pushed the political reform forward. Lee was allowed to enter the Chinese land again for a two-day visit, which aimed to gain support from the Democratic Party. It has been another era since Xi Jin-ping became the president. The relationship between China and Hong Kong has deteriorated rapidly in these 7 years.

The last battle defending One Country Two Systems

Due to dissatisfaction with the postponement of the implementation of universal suffrage and the political reform proposed by Beijing, the Occupy Central movement was initiated by three co-founders in 2014, hoping to devise another political reform proposal among citizens. This in turn led to the Umbrella Movement in September of the same year.

Hugely influenced by the Sunflower Movement in Taiwan, the 79-day Umbrella Movement ended with the police clearing the camps and barriers in the occupied areas, leaving an even deeper rift and greater tension between Beijing and Hong Kong. Street protests and conflicts between China and Hong Kong became more severe, along with the rise of localists.

Later, the Hong Kong Government disqualified the legislators and candidates who advocated for the independence or self-determination of Hong Kong. Through reinterpreting the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law, Beijing has declared its absolute authority in Hong Kong.

In June 2014, the State Council of the People's Republic of China (PRC) published “One Country Two Systems White Paper”, officially announcing that the Central Government was entitled to “overall jurisdiction over Hong Kong”. Just before the 20th anniversary of the handover of Hong Kong, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC claimed that the Sino-British Joint Declaration is a historical document which carries no realistic meaning. That the governance of Hong Kong by the Central Government is not bound by the terms set out in the Declaration since the UK is no longer entitled to the sovereignty of Hong Kong, and the right to rule and supervise Hong Kong.

When the controversies over the Extradition Bill first broke out in June 2019, all Chinese state media reiterated clearly the statement claiming that the Sino-British Joint Declaration is outdated and expired. Still, the new interpretation of Article 22 of the Basic Law was even more shocking.

Sudden reinterpretation of Article 22 by two Offices—the article that once gave Martin Lee relief

On the night of 18 April when Lee was arrested, the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in Hong Kong along with the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office reinterpreted Article 22. This was an important article guaranteeing the two systems in Hong Kong, which clearly states that all departments of the Central Government cannot intervene with most affairs in Hong Kong. Yet, these two offices claimed that since they do not belong to “any department of the Central Government”, they are entitled to supervise the affairs in Hong Kong. Such a statement shook the entire city.

Did the Drafting Committee discuss the definition of “two systems” in Article 22 at that time? “Not at all. We never discussed this.” Thinking of Article 23 which sparked heated debates since the drafting of the Basic Law and took 30 years to reach a consensus, Lee never imagined that Article 22 would become the focus of the argument between China and Hong Kong. In fact, he felt relieved because of Article 22 at that time—this article makes a clear definition of “two systems” and is the cornerstone of the principle of One Country Two Systems.

On the other hand, some scholars claim that as the Basic Law had already been passed in the National People’s Congress, their statement is no different from turning the Sino-British Joint Declaration, an international agreement, into a national law, which means that violating the Basic Law is equal to violating the Constitution.

When Lee dealt with the British, they talked about rule of law and values—they pursued professionalism, decency and self-discipline.

Yet, what he and Hong Kong democrats are now facing is a resilient political party, once almost defeated by the KMT, that managed to get to the house caves in the Loess Plateau miles away, and made good use of their flexible united front strategy to survive being besieged by Communist International, the Soviet Union and the West. Now, the CCP is literally the biggest, strongest and richest authoritarian regime with the most advanced technology on earth. It is not difficult for a competitor who does not care about decency to tear up a contract in front of everyone.

Talking about the laws—insisting “two systems” is the way to protect Hong Kong

In fact, repeated harsh words from Beijing are not news. The “two systems” is indeed in the process of breaking down. Every time Beijing takes one step forward, the breakdown speeds up.

Li Yin-wo, who witnessed the cruelty of this power and avoided the CCP his whole life, reminded his son before he passed away in early 1989, “Be careful when you deal with the CCP. When they want to take advantage of you, they can give you everything. Once you lose your value, they will not only abandon you, but also step on you.”

Even though the international community was shocked at Lee’s arrest on 18 April, thus confirming that “One Country Two Systems” is dead, Lee still insists that Hong Kong is not under One Country One System yet.

“Just like we have to conform to the Chinese constitution when we are on mainland China, if someone is convicted of murder in Hong Kong, that person will not get a death penalty, but it can happen in China. The driver is on the right in Hong Kong but on the left in China—this proves that the legislations are different. Even China won’t say that it’s one country one system because Hong Kong is still very different from Guangzhou, either in terms of the legal system or the elections.”

He firmly believes that One Country Two Systems is the only thing that can protect Hong Kong. It is stipulated in the Sino-British Joint Declaration, an international agreement, and in the Basic Law which makes it legally binding. Lee thinks that Hong Kong still has bargaining power and his strategy now is to voice out everywhere, asking the international community to pressure Beijing into sticking to their promises. The elder never says no easily. “I won’t give up. I won’t feel that there’s no way back.”

Yet, it seems that the youths cannot understand Lee.

Everyone’s own generation, Everyone’s own revolution

Along with the rise of localism in recent years, some localists criticized the pan-democrats led by Lee at that time—those who supported the democratic repatriation and One Country Two Systems indeed took Hong Kong to the same path as Tibet. He cannot forget on the third day of the Umbrella Movement in 2014, when a 19-year-old girl ran to him and asked while crying, “Why did you accept One Country Two Systems at that time?”

“I asked her if she meant we should go for independence. If we want independence, it requires a revolution. But the UK would not support that and China would only send the army even earlier to take Hong Kong. Who in the international community would help you? Would that really be better?” The girl did not answer him. He then said to the girl, “if we didn’t accept One Country Two Systems, there would be no better choice than leaving Hong Kong. If you want a revolution, you can do it by yourself. Don’t blame us. But you also know the cost.”

In 2019, the revolution broke out in Hong Kong. The youths in Hong Kong paid the price with blood, tears and sweat.

Lee thinks that as Beijing has broken their promises again and again, he can understand why the youths protest violently, but he doesn’t agree with it because he thinks it is ineffective. This outstanding lawyer, who likes to speak as a matter-of-factly, seems unable to see through politics —countless times of useless resistance and the unswerving will to do something in a bid for impossible success can elevate a group. What the community has suffered will be told from generation to generation, keeping the fire of democracy going forever.

In 1998, Lee could still lead the Democratic Party to be the largest party in the Legislative Council by winning 40% of the votes, and stick to the promise “We Shall Return.” Yet, the younger generation including Edward Leung, Joshua Wong, Agnes Chau and 8 other legislators who won the election, could be deprived of the right to participating in politics easily. The space to express their opinions is shrinking rapidly, and the energy must be vented on the streets.

On 16 November 2019, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) was under siege—it was almost the end of the 6-month Anti-extradition Bill Movement. 100,000 Hongkongers rushed to the surrounding areas of Mong Kok, Jordan and Tsim Sha Tsui. The main roads in Kowloon were destroyed, completely covered with scattered bricks all over. Molotov cocktails were flying in the air from time to time. It was like that there was a magical boundary. The frontline fighters were actually very frightened. Some secondary students even trembled. The protesters could only carry on by reminding themselves of those who suffered—citizens being beaten up in Yuen Long by men in white and police at Prince Edward Station; the first aider who was shot in the eye; young men and women whose dead bodies were found at sea or fell from buildings.

Indignation is the fuel of courage and the fuel has to be burnt to turn fear into ashes. The immense changes Hong Kong went through led Lee to ask himself this question many times: were there alternatives back then?

“If Hong Kongers believe in the CCP, we would not be here now. I do not regret supporting One Country Two Systems at that time because we had no choice,” said Lee. Looking back, if there was no Sino-British Joint Declaration, Hong Kong would have returned to China without any protective rights from 1997.

Different from many pan-democrats from the older generation, he is open-minded about discussions on self-determination.

“I do not support independence, but why can’t we discuss self-determination? This is freedom of speech. The youths have their own thoughts. They may make mistakes but so may we.” Lee reiterated, “I support peaceful resistance but not violence. Yet, if the youths did not protest and give pressure with a small degree of force in June, the Extradition Bill would have been passed already. At the end, it was withdrawn successfully. That’s why we are grateful and did not draw a line between us and them. Also, they won the hearts of people around the world. Only history can prove right and wrong. The main point is that they are able to think independently. I always defend the youths.”

In the end, the millions of people on this island still fail to escape from their fate after 50 years—they are still ruled by the CCP, but everyone in every generation has their own roles and duties, limitations and creativity.

Though he has already seen the abyss

The special characteristic of the Chinese democracy is that the party and its leader always outweigh the rule of law. In order to establish the legal basis for One Country Two Systems, the Hong Kong SAR government was created under the Chinese constitution. However, the rule of law is an abstract concept and its continuity relies on conceptual restraint and self-restraint of authority. Hong Kong’s position is particularly vulnerable in a motherland where logic is derived from its authority.

This vulnerability is presently on full display as Beijing paves the way to enact the National Security Law under Article 23 of the Basic Law.

Luo Huining, the newly appointed director of the Liaison Office, emphasised that Hong Kong is “the broken window in the country’s national security”, implying that Beijing can no longer wait to legislate Article 23. The whole world started to point their guns at China because of the pandemic. Beijing must not allow Hong Kong to become the base for subverting its power.

In contrast, Lee appeared naive in his commentary published in December 2019. The six-month-long struggle in the Anti-Extradition Bill movement has left societies in Beijing and Hong Kong with little room to manoeuvre. He still hoped to persuade Beijing that extreme leftists tactics cannot resolve the problem, that they should trust Hong Kongers and allow the true implementation of One Country Two Systems.

“Hong Kong is an example of how China will take Taiwan. The way Beijing treated us (referring to the arrest on 18 April) implied that they think One Country Two Systems has already failed. What will they do to Taiwan then? Only two possibilities. Either they do nothing or go for war.” Lee, who has always been mild-mannered, gave an unusually sharp warning but he still has reservations.

“If they let Hong Kong go back to the way Deng had promised, everything would be different. Hong Kong, Taiwan, the international community would all be happy about that. It’s not hard for one’s mind to change. This depends entirely on Beijing.”

Lee still believes that as long as Beijing is willing to stop interfering and grant Hong Kong universal suffrage, which it deserves, everything can be great. But can this wonderful dream ever come true?

On the other hand, Leung Kwok-hung is rather pessimistic about the future of Hong Kong because he thinks it is impossible to expect Beijing to change its attitude. He believes in the theory of a “democratic repatriation”- the destinies of Taiwan and Hong Kong are interwoven with that of China. If China does not put an end to one-party rule, then Taiwan will not be able to remain unchanged and Hong Kong will not be able to adopt a genuine One Country Two Systems.

Yet, Lee does not think so. “This is the promise written in the Basic Law. Why does Hong Kong have to wait for a democratic China to gain democracy?” He said, “Of course, as a Chinese, I am not selfish. I also hope that China can have democracy. This is a birthright. I won’t force Beijing to grant democracy in mainland China. But the CCP should be self-confident and know that putting an end to one-party rule is good for everyone.”

The last knight of the city, Martin Lee, is defending the city which belongs to 7 million people. This citizen, with his stage in the international community and not in mainland, insists that the Basic Law is the law every free citizen in Hong Kong should comply with. He thinks that One Country Two Systems can at least protect Hong Kong for 27 more years but this wall is being destroyed, and there’s no need to deny it further.

Martin Lee’s thoughts are more like a will. He does not seem to be disappointed in humanity even if he has already seen the abyss. Trying hard to look for light in darkness, no matter how difficult, he still wants to give each other a chance.

Source: https://www.twreporter.org/a/hong-kong-extradition-law-interview-martin-lee-chu-ming?fbclid=IwAR3teyjAdACFKoJDBx3isRMqZhjykS08Z3s-2r5Dr43engKrYsG6UTpgBIY