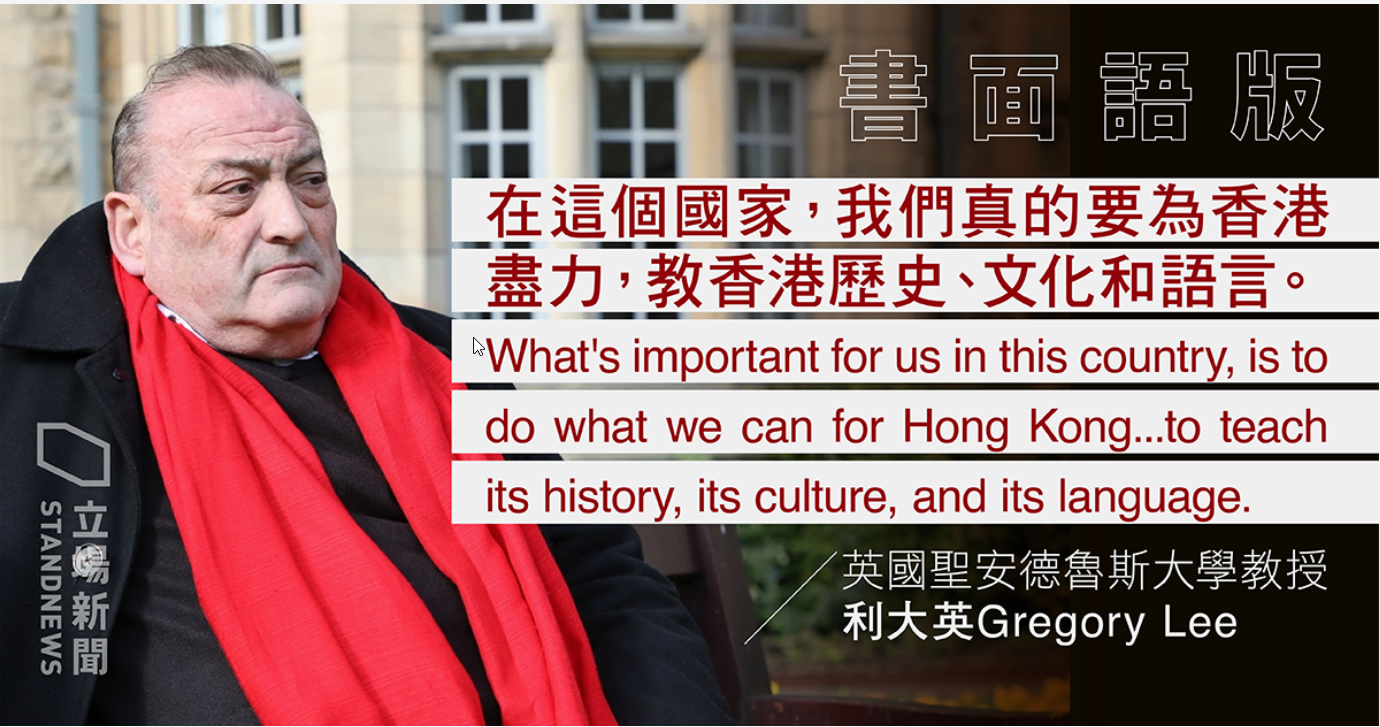

[Interview]: Creating a Hong Kong culture module in a renowned British university—Gregory Lee on changes of Hong Kong over half a century

Translated by the Guardians of Hong Kong June 26, 2021

The United Kingdom (UK) government announced the introduction of British National (Overseas) (BNO) visa in July 2020. One month later, Professor Gregory LEE moved back from France to St. Andrews, Scotland.

He heard about the BNO visa on the news. “That means thousands of Hongkongers will come to the UK. What will happen to them? How much room will their next generation have in discussions about Hong Kong?”

The more he thought, the more Lee felt the need to do something as a scholar – which he wanted to but did not have the chance to do — to create a university module on the culture of Hong Kong, Macau and Cantonese language.

“If the next generation of these Hongkongers does not want to learn Cantonese and Chinese, we should not force them. But if they do, we should provide assistance.” Lee says. “I want people to know St. Andrews will become a hub for everyone who come to the country to get to know the Hong Kong culture as well as to pass it on to the next generation.”

You may ask why he wants to do so much for Hong Kong.

“The main reason? Because I really like Hong Kong.”

The second reason is that discussing Hong Kong can assist Britain understand its own history. He feels that Hong Kong formed a very important part of modern British history. “Through Hong Kong, you can trace back the ups and downs of the British Empire.”

His third reason is moral responsibility.

“I have been teaching for over 20 years in France. They don’t have much understanding in Hong Kong. But this is the UK. Britons should be familiar with Hong Kong as the UK had taken so much from Hong Kong. The UK was, is and will be in a position too important to Hong Kong.”

“Therefore, I think we should do our best in this country for Hong Kong, to teach its history, language and culture. Only by doing this, we can let the Hong Kong community know at least one part of the education system is telling their story.”

At this point, Lee pauses and asks, “Am I too sentimental?”

The interview takes place in St. Andrews.

Although it is early May, we still feel cold in Scotland. The temperature can go down to 2 degrees. Under the Wuhan pneumonia pandemic, the campus of the University of St. Andrews is still empty as face-to-face classes are still suspended.

St. Andrews is well established with over 600 years of history. It is the oldest university in Scotland and the third oldest in the English world, only after Oxford and Cambridge. In terms of ranking, it is always within top 5 in the UK. Its famous alumni include John Campbell (4th Governor General of Canada), Alex Salmond (former First Minister of Scotland), Rudyard Kipling (English writer), Robert Watson-Watt (inventor of radar) and Edward Jenner (father of immunology)... On another note, Prince William and his wife Kate first met at St. Andrews, their alma mater.

When it comes to Hong Kong, it really has not much to do with St. Andrews. If Lee did not take up the post as founding professor of Chinese studies in the University of St. Andrews last July, its module on Hong Kong would not exist.

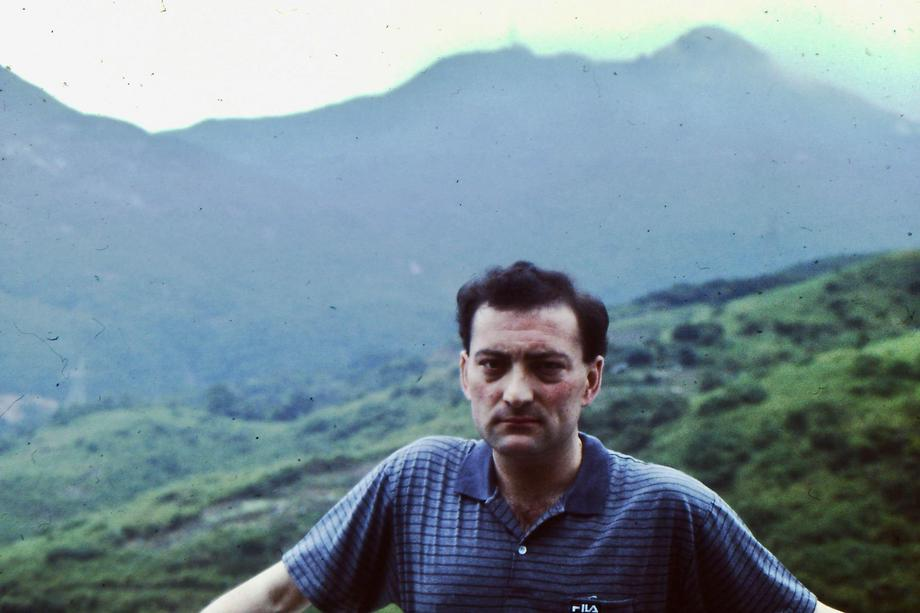

Lee has every reason to organise this module. This is not just because of BNO. He has deep ties with Hong Kong. Between 1994 and 1998, he was an associate professor in comparative literature in the University of Hong Kong and he taught Hong Kong culture together with the late poet Yesi. Lee would teach the first half which was on the First Opium War and the opening of the port of Hong Kong whereas Yesi taught the other half.

“I witnessed the development of Hong Kong’s culture.” Lee says.

Afterwards he left Hong Kong and taught in another place.

He was back in Hong Kong from 2010 to 2012 to take the position of the founding dean of the Hong Kong Advanced Institute for Cross-disciplinary Studied as well as the dean of the college of liberal arts and social sciences. In 2011, Lee was elected as a fellow of the Hong Kong Academy of the Humanities.

Outside Hong Kong, Lee also taught in University of Cambridge, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) of University of London and University of Chicago. Before his appointment in St. Andrews, he taught in Jean Moulin University Lyon 3 in France.

If you spend some time researching on the internet, you can find news of Lee in Lyon 3. In 2013, Lyon 3 became the first institution in France terminating its cooperation with China in organising the Confucius Institute.

Of course, this had something to do with Lee. He was the head of the Department of Chinese then. After the end of the relationship, Lee explained in a BBC interview: At the beginning, the university insisted that the Confucius Institute would not interfere with academic independence. However, later on Chinese representatives started to interfere with the contents of the courses and intended to take part in the teaching and research parts of the Department of Chinese. Lee refused but they insisted on their demands and threatened to take away their funding. As a result, Lee ended the cooperation.

“Exchanging ideas with and teaching Chinese students are what we always willing to do because these are our job as scholars,” he said. “However we cannot become the mouthpiece of the Chinese or British governments. This is not the job of a scholar.”

On another note, Lee had already started a module on Cantonese in Lyon 3 back at that time. At that time, identity of Hongkongers was not yet widely talked about. After all, that was 2013, even before the Umbrella Movement.

What is Hong Kong culture in the eyes of this scholar who has deep ties with Hong Kong?

“Many always say Hong Kong is just a financial centre, a place to make money. This is clearly wrong. Many people fled to Hong Kong during the Cultural Revolution not because of money. But it was for survival, for politics, cultural and religious reasons.... One more thing, there is something I didn’t like and I still don’t like. It is when people say Hong Kong is the ‘Pearl of the Orient’ and ‘where east meets west. I think these kinds of description are rubbish. What does ‘where east meets west’ even mean?”

“I would say there are lots of things we need to clarify in the history of Hong Kong. What I have always wanted to do is to go beyond these kinds of old viewpoints.”

The module Lee creates for the University of St. Andrews is called “Pearl River Cultures”. He put 11 asterisks next to the courses on Twitter:

*History of Macau

*Macau's Languages

*History of Hong Kong

*Colonialism and (de)colonial cultures

*1950s Hong Kong: Exiled Cinema, Emigre Writers

*1960s-1980s: Cultural Re-Invention of Hong Kong

*Cantonese - a literary language?

*Hong Kong Cinema

*Music in Hong Kong

*Post-1997 Challenge to Hong Kong Identity

*HongKongers in the UK

His understanding of Hong Kong from his whole life is illustrated in the name of the module as well as these 11 asterisks.

* * *

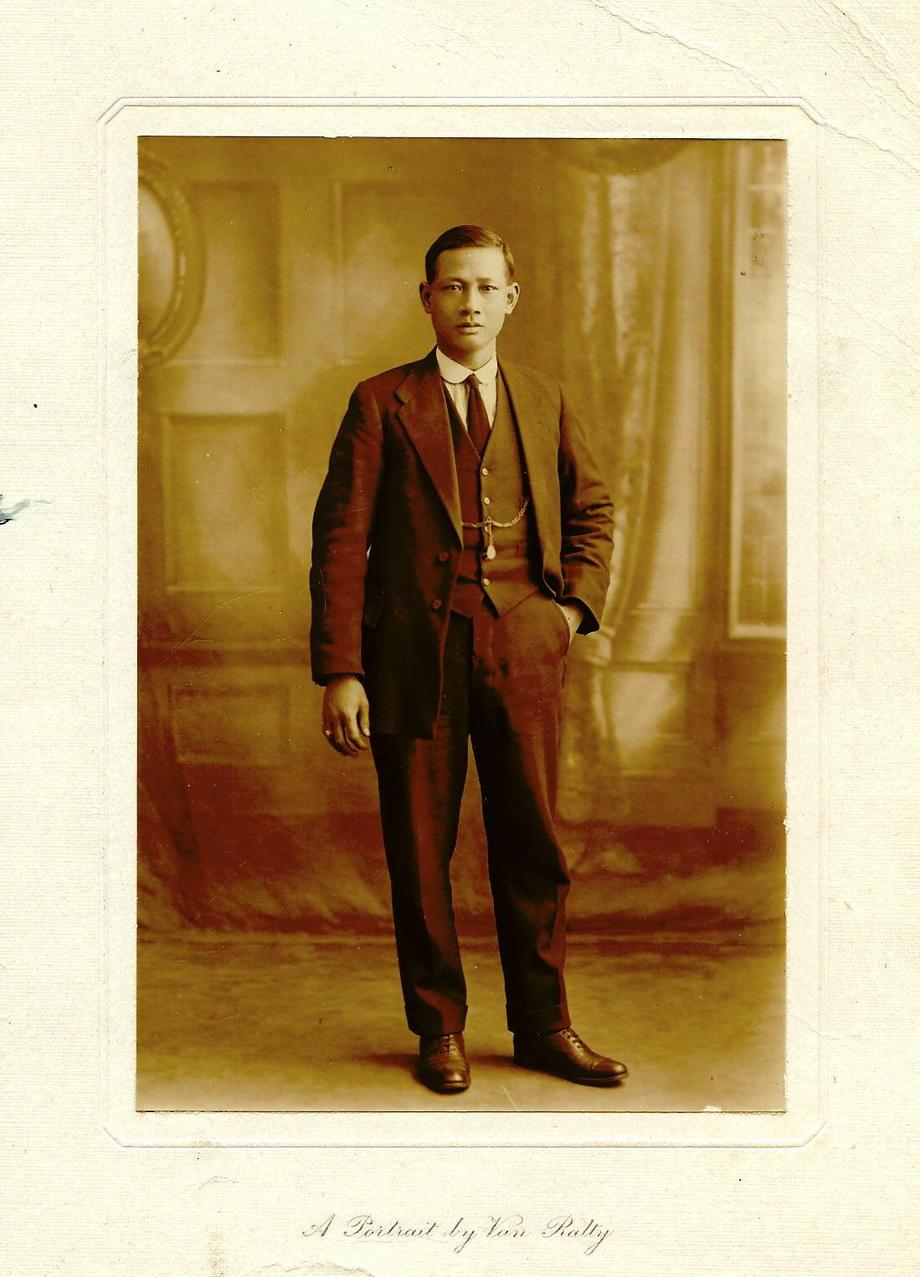

Lee was born in Liverpool, England in 1955. His father was Irish but his maternal grandfather was Chinese whose name was CHAN Chuen-Lee. Chan was born in Foshan and had lived in Macau. He was a sailor, having spent most of his life overseas just like a lot of other Chinese in the 1910s, and came to England in 1911. When Lee was young, his grandfather would take him to visit the Chinatown and its Chinese shops. Lee would quietly stand on one side and observed the actions of Chinese people in Chinatown.

He knew that after coming to England, his grandfather always wanted to return home, just that it never happened. His grandfather chose to, or did not have any options but, stay in England.

“To me, it was a good thing.” said Lee.

“So that I could get to know him more and that also cultivated my hobby.”

His Chinese name Lee Tai-ying was borrowed from his grandfather. The Brits called his grandfather Chan Lee or C.C. Lee so they mistook his surname as Lee. Gregory simply took Lee as his surname. (His initials were GB, the same as that of Great Britain. So he used Tai-ying (meaning Great Britain) as his Chinese first name.)

Chan passed away when Lee was 8 but he influenced Lee’s whole life. Lee originally wanted to study law in university. But out of his interest in Chinese, he turned to studying Chinese at the SOAS of University of London.

“It was in the 70s and my classmates were either interested in Mao (Ze-Dong) or Tao(ism). So they were either Maoist or Taoist. I was interested in neither of them. I stood between them and looked at either side from time to time....”

Apart from the formal classes, a few teachers from Hong Kong taught Cantonese on Saturdays and Lee was one of their students. Hong Kong, Macau, China.... these familiar yet at the same time unfamiliar terms were like dreams to Lee.

In 1978, before completing his university study, he left Europe for the first time for Taiwan to attend a summer course at the National Taiwan Normal University. En route he had to stop over at Kai Tak Airport in Hong Kong. Through the window of the plane, he saw the Pearl River and its surrounding mountains. At that moment, tears dripped from his eyes. He felt like coming home.

After completing his bachelor degree, Lee continued to study. Between 1979 and 1986, he received a scholarship from the British Council to study economics and politics in Peking University. After that he went back to SOAS to complete his doctoral degree in Chinese literature. Subsequently, he returned to the literature research unit of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (formerly part of Peking University) to continue his research work.

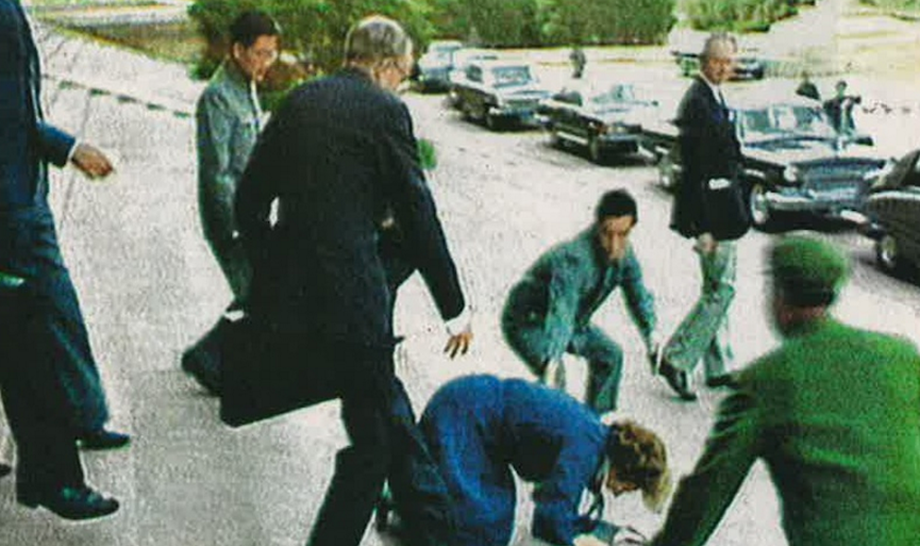

The Sino-British Joint Declaration, which was said to be a “historical document” by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was signed in 1984 and come into effect in 1985. Lee witnessed the course of this history changing negotiation at the right moment in time. On 24 September 1982, the Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher met Deng Xiao-ping to discuss the future of Hong Kong. After the meeting, she tripped over when walking out of the Great Hall of the People. Hong Kong also tripped over when she did. On the next day, Thatcher joined a dinner held at the British Consulate. Lee, being a distinguished student, was also present. When asked about his impression on Thatcher, Lee said, “To be honest, I don’t think she had any feeling towards Hong Kong.”

Lee felt that the UK poorly handled the handover of sovereignty. In fact, he felt the overall colonial rule of Hong Kong was very poor.

“Hong Kong was seen as a separate place. It seemed like we (the UK) didn’t have to care.”

Lee once wrote an article on the handover of sovereignty of Hong Kong and it contains a phrase “Selling Hong Kong up the Pearl River.”

* * *

In order to have a deep understanding on how Lee sees the Hong Kong culture and his motif of setting up this module on Hong Kong culture, you have to understand his criticism on the British colonialism. Yet, you need a bit of patience and effort to discuss colonialism in Hong Kong nowadays.

This is because nowadays, anti-colonialism is seen as pro-China. In other words, objecting to colonial government is seen as equivalent to welcoming the handover of Hong Kong back to China, which is in turn equivalent to supporting the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Actually one cannot blame this kind of logic. If one looks back in history, in the 60s, 70s and 80s, there were anti-colonial intellectuals in Hong Kong who connected the rebellious, anti-colonial mindset to the “Great China” nationalism.

However, this is not what Lee means.

His criticism on the British colonialism was about its passing of a set of cultures from the colonial government to Hongkongers and this set of cultures had immense influence on the development of Hong Kong.

Lee believes in the centrality of culture in many issues, including politics.

Take “China” as an example. Some say the territory of China is holy and cannot be invaded. But what is “China”? In 2018, Lee wrote about “how China became ‘China’” in his book “China Imagined”. In the book he said, “We always see China as an everlasting place with a continual history of 5000 years. But in fact, “China” first existed as the name of a nation in the 16th century in Europe. The term “China” was not widely used until the mid 1800s. Regarding the idea of China that we know today, Lee thought, to some extent, was the product of the May Fourth Movement (the promotion of vernacular language, the spirit of science and democracy and the overhaul of Chinese traditions). “The Movement created China instead of vice versa.”

And let’s take “Hong Kong” as an example. Many Hongkongers see themselves as part of and care about Hong Kong. But actually what is “Hong Kong”? “Obviously it is not about the physical land of Hong Kong. How many people can really own the land of Hong Kong?” Lee said, “It should be about their shared history, language and tradition” which is the Hong Kong culture.

Culture is actually the core of everything. “It is culture which creates politics, not vice versa.” This is Lee’s belief.

In fact, Lee was designing the module on Hong Kong in St. Andrews bearing this in mind. You can see he named one of his modules “Chinese studies” rather than the more commonly seen “China studies”. It was Lee’s proposal that we should discuss Chinese as a culture rather than China as a country.

In the same way, Lee decided to name his course the Pearl Culture because he felt it was easy to divide Hong Kong, Macau and the surrounding areas into different districts politically and geographically. However it was very difficult to divide them culturally.

“When you think about Hong Kong, you cannot miss out Macau. How many people lost all their money and returned Hong Kong with their pocket empty? Even if we don’t talk about the kingdom of Stanley HO, to many people, especially the older generations, Macau, Guangzhou and the surrounding areas were closely related.” Lee’s grandfather was one of them.

Why does his module teach Cantonese? Although Putonghua is the official language in China, culturally speaking, the importance of Cantonese is not inferior to the former.

Also out of the same reason, one of the asterisks on his modules is to explore Cantonese as a literary language.

“See! People use Cantonese in popular culture such as dialogues in comics and movies but rarely in poetry. Why? And for example, in novels, sometimes you see dialogues in Cantonese but not elsewhere. Why not?”

“I think it is because people still fear that using Cantonese will detach from the centre of “Chineseness”. They feel using Hong Kong style Chinese in poetry will lose certain readers.... This is because they don’t have the confidence that Cantonese can be used to produce masterpieces.”

“Of course you can!”

Politically speaking, Hong Kong may be small. It is just a special administrative region in China. Geographically speaking, it is also small, comprising only 1,106 square kilometers out of the 9,597,000 square kilometers. But culturally speaking, the Hong Kong culture is parallel to any other culture.

There are masters and servants in politics. There are large and small places in geography. But there is no better or worse in culture. Hong Kong culture is Hong Kong culture. This was Lee’s thought.

Politically speaking, in 1997, the sovereignty of Hong Kong was indeed handed over from one country to another. But if you think culturally, the Hong Kong culture would not change overnight. Lee thought the colonial mindset left behind by the colonial government stays deeply among Hongkongers.

From 1994 to 1998, when Lee taught in the University of Hong Kong, he was not happy about its deep vibe of colonialism. “You could totally see how white people were seen as superior.”

This is not just a racial issue. In 2010, Lee was teaching in City University of Hong Kong. “Alright, your boss is not white anymore.” He thought Hong Kong would change. But he found out the situation was still the same.

“You can still see some people are very obedient and do whatever they think can please mainland China.”

“Is it okay as long as those in charge are Chinese? And that will be better than the white people? Maybe. Some may feel happier. But I don’t think so. I think university should be an organisation of free thoughts. Everyone should have autonomy and be able to express themselves.”

What Lee criticised was the mindset that was unwilling and afraid of challenging the authority. He felt this mindset was rooted in colonial rule. Back then, the colonial government wanted stability and hence did not want Hongkongers to talk about politics. From educational to cultural, all policies aimed to turn Hong Kong unpolitical. They only wanted to talk about livelihood but not politics. “The problem with Hong Kong is everyone faces an unaccountable authority.” After some time, Hongkongers lost the sense of autonomy and did not think they can determine their own fate.

“Don’t rock the boat. Don’t play with politics. Don’t make changes....” Lee said. “I think this is very wrong.”

Lee thought 1997 could be a chance that Hong Kong once had to detach from colonialism and restart. It was a pity that that did not happen. What happened was only the change of the source of authority.

“The Brits and the Chinese used the same methodology to maintain the same authority.”

Lee thought it was most likely the Brits’ fault that Hong Kong missed this opportunity. Over the span of over a hundred years, the UK obtained a lot of economical advantage. But when they left, they did not leave behind the opportunity to be autonomous.

“You cannot simply build something and leave without saying anything.”

You can imagine how uncomfortable Lee felt when he saw Hongkongers raised the flags of UK and colonial Hong Kong.

“I understand that it is easy to feel nostalgic. When you see the situation Hong Kong is in now, some people will miss the British colonial rule,” he said. “However colonial rule is colonial rule. It has no fun at all.”

Lee thought that in this time and day, too many people like to blame China for anything. It seems that anything China does was wrong and if something is not done by China then it had to be right. Without hesitation he said, “Our biggest mistake is to say that everything is the fault of China or Chinese people.”

His criticism was equally applicable to Hongkongers as well as the Brits. The UK government frequently criticises human rights issues in China. Lee thought this was not wrong, just inadequate. “They also need to look back on their own history. If they don’t, their words would not be listened to.”

There is another reason why Lee does not agree to blaming everything on China. To him, “China” was a very ambiguous idea. In his eyes, China is not a monolithic entity. We can take a look at Chinese culture. There is Shanghai culture in Shanghai and Guangdong culture in Guangdong. Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong and Taiwan each have different cultures. What does Chinese culture mean? Furthermore, culture changes over time. The CCP tried to destroy the Four Olds and promote the Four News.

Some people demolished Confucius statues while years later they establish Confucius Institutes. When people mention Chinese culture, which period do they mean? Whose culture? Which place?

Lee even thinks the term “anti-communist” is problematic. He says he has had many students over the years, some from China of whom many belonged to the CCP. They did not necessarily love the party. But in China you have to join the party in order to do many things. Lee asks, if he has to be “anti-communist”, does that mean he has to be against his own students?

“What I want to say is the statement from top down is a discourse. But, on the other hand, within the spectrum there are many different discourses.”

Lee sees China that way. As a scholar, he wants to present the complexity of reality. After all, the world is really not just black and white. But sadly in this era, when he says he disagrees with Hongkongers raising the British flag and we should not blame China for everything, he may be labeled as pro-communist.

Lee is not naïve or stupid. He knows his opinions do not fit the current political atmosphere. But exactly because of it, he feels an increased need to express his views. This was also his reason to organise the module on Hong Kong culture.

“Even if it will not be pleasant, you should still be open to discuss these histories, right?”

* * *

The Stand News got more than 20,000 likes on its social media post about “Hong Kong culture” module organised by Lee. The author reads the comments and found that many sighed, “Things that can’t be done in Hong Kong, can only be done overseas now.” The author believes that the emotions of the general public who liked the article are influenced by recent incidents such as the perceived threats on academic freedom, the oppression of the Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), the removal of RTHK online archives, etc. Many have a sense of danger that the Hong Kong culture is going to die and that makes Lee’s module precious.

We have discussed that Lee not being “anti-China” or “anti-communist”. But he agrees that academic freedom was one of the reasons to organise this module. He also admits that while the University of St Andrews is not situated in China or Hong Kong, the module may be able to tell the story of Hong Kong even better.

However, he does not think that Hong Kong culture would die out anytime soon.

He recalled the memory of his first trip to Taiwan in 1978. Chiang Kai-shek had only passed away for 3 years then. Taiwan was still in curfew. The Formosa Incident was going to happen one year later. Even the book he carried written by LU Xun was prohibited. At that time, mainland China was more open than Taiwan. That was the time of having the Democracy Wall in Beijing. People could post their thoughts on the Democracy Wall outside Tiananmen Square. Lee could read the books he liked and meet the people he wanted to meet.

Taiwan’s curfew was lifted in 1987. He visited again around year 2000 and the society of Taiwan was totally different.

Of course, China was very different too, in another sense.

“The modern Chinese history is full of ups and downs. It is full of unpredictable moments.” Lee said. “For example, if you asked me 5 years ago what Hong Kong would become. I could not have imagined how it is today. Who else could?”

“That means sometimes even if you can predict the way things will happen the outcome might still be different. History tells us to be optimistic.”

Organisations outlawed would disappear. Members of Parliament disqualified would leave their jobs. These are hard politics.

But culture will not disappear just because it is not talked about on textbooks or in classes. Many Hongkongers are upset by the removal of RTHK programs. Lee knows about that too. But as a scholar, he would say in the thousands of years of history, uncountable amount of documents disappeared and some events did not even have any documentation. However people in the future can still trace back and reproduce these lost things.

“Culture cannot be easily killed off. Just like language, unless you kill the last person speaking the language, otherwise this language will stay forever.”

In Lee’s module, the last asterisk was on Hongkongers in the UK. He hoped the dispersed Hongkongers can have the chance to know where they came from and learn the language of their culture.

“We have the duty to do so.”

The module was still in its planning stage. Because of the pandemic, Lee can spend time at home to prepare the details of the module. For example, whether he should organise a Cantonese class in summer? How to integrate it with Traditional Chinese studies bachelor degree? On top of these, classes at master and doctor levels and post-doctoral research…. Lee is also planning whether he can set up two or three other courses on certain topics such as movies.

He laughs (although he is serious) and says what he needs most is resources. The problem is if you want to do Chinese studies, you can go to Confucius Institute. For Taiwan studies, you can call their government for resources. There is no such resource for Hong Kong. Lee hopes to find sponsor to support his modules. In particular, he wants to support master students on their researches to create an academic environment for research on Hong Kong culture at the University of St. Andrews.

There is no such generous sponsor at the time of the interview. But Lee says after the initial report by the Stand News on his module, many contacted him to offer help. They asked Lee whether he remembered them. They said they were his students back in 1992-93. Someone said Lee’s reference letter helped them obtain scholarship.

“Of course I do remember them.”

When he was young, his grandfather inspired his interest in Hong Kong. Decades later, his interest had developed into the bonding among people. Lee remembers his students and colleagues. Some stayed in Hong Kong while some were oversea. No matter where they are, those who contact him actively still care about Hong Kong and its culture a lot.

When there is light, there are people. When there are people, the culture will not die.

Source: Stand News, #May19

Author: Mok Mok

#UK #University #HongKongCulture #GregoryLee

https://bit.ly/31DOe8k (archive.org)