In My Mother, a Fear Stripped Bare

@americanwords

My mother liked to drink tea in the afternoon, when the weight of the day had sunk in and the heat was still and heavy. This was in our walled-in backyard in Tehran in the early 1980s, after the Iranian Revolution had changed everything.

My parents were doctors, and under the shah they and my older brothers had enjoyed the kind of privileged life such positions would normally afford: frequent trips abroad, a nice house with a swimming pool, other luxuries.

But in the years right after I was born, when the Islamic government came to power, our foreign travel ceased, our swimming pool was drained, alcohol was forbidden (though my parents kept it hidden in sugar jars) and, despite having friendships that stretched back decades, my parents no longer knew whom they could trust.

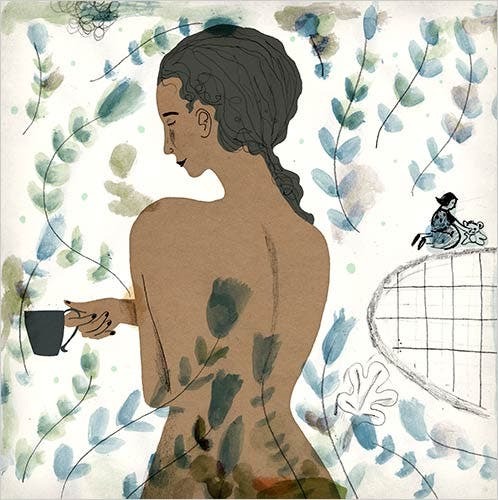

On those oppressively hot afternoons, my mother used to take her glass of tea, place two sugar cubes delicately between her lips, and sit in the garden while I played with my toys in our empty pool as if it were a giant concrete playpen. She sat on the ledge and slowly unbuttoned her shirt, let it slip from her shoulders, and allowed her skirt to fall loose.

Baba, our cook, was blind and Nabi Khan, my nanny, was asleep by this hour, so my mother would take her time to undress. Just steps away, on the other side of the wall, the Pasdaran stood guard, their Russian-supplied AK-47s strapped on their backs.

My mother had reason to fear them; they had raided our home many times already, looking for liquor or other illegal comforts of our previous life. Women had been whisked away and imprisoned and brutalized for the slightest transgressions like wearing lipstick or being improperly dressed. Despite this, she seemed boldly unafraid as she lounged half-naked in the garden with her tea, dreaming of a faraway place.

Her rebellions were daily, but covert. She did not raise her voice against the Iranian government or cake makeup onto her face. She did not protest at rallies or burn flags. She simply wore no clothes underneath her hijab in silent but nevertheless risky dissent, an acknowledgment that her femaleness, her nakedness, was her most dangerous weapon.

Years later, when my family was nestled safely in the Maryland suburbs, I always meant to ask her about her ritual. If I had, I imagine she would have simply answered, with a twinkle in her eye, that the heat was stifling.

I respected my mother. Like any immigrant child, I knew my parents had sacrificed and worked hard for our material possessions. I was told of a land where women had to cover themselves, where they couldn’t play soccer, where there were no Girl Scouts.

I figured, on some level, that my mother hated Iran. It had become, after all, a country that she could not have imagined. While women used to get in trouble for wearing the hijab to school under the shah, they then received lashings and beatings for not wearing them properly under the Islamic government. The country swung from one side of the religious pendulum to the other. Or perhaps the clock just stopped working. All I knew was that my parents had left their homeland at my mother’s insistence, that our flight must have been driven by hatred and that she was fearless to drag her family across the world.

Yet while many in the West hated Iran, I continued to love the only home I had ever known. I had learned to speak on its shores, taken my first steps on its soil. How could I turn my back? The issues for me were not political but internal and cultural. I was bitterly angry at the government and the clerics, but I felt remorse for Iran’s people. And as things fell apart there, my sadness was palpable.

But having spent only the first five years of my life in Tehran, I had trouble parsing fact from fantasy. While I remembered clearly the ritual of those backyard afternoons with my mother and powerful moments like learning Farsi in preschool and being punished if I refused to scream with my classmates “Death to America,” I often did not know if other memories were real or plucked from the nightly news. I did not know what Iran was, or what it represented. For me, it was an unintelligible jumble of emotions, from shame and resentment to love and sadness. It was like being in an abusive relationship with someone you can neither love nor leave.

So I mourned on one side of the ocean while the country we fled struggled on the other. People mocked Iran and called me an enabler whenever I said anything positive. I cooked Persian food in my kitchen, savored the taste, but then spent hours scrubbing pans angrily. I did not know what Iran was anymore; it wouldn’t even let me in. At home, my parents were silent on the subject. Did they not miss anything about their homeland or its people?

In school, the other students taunted me for my foreign name and lamb-based lunches. I made the mistake of telling them I was from Iran, and the ridicule the camel jokes and the seventh-grade slurs never ended. I wished I were Russian or even Iraqi. Those children were left alone.

But my mother said nothing. There were no more harrowing tales of where we came from, only the common refrain that you love the country where you pay your taxes. And so she laced my jet-black hair in pigtails with ribbons and trimmed back my unibrow and said, “You are an American.”

And for a second, I believed her until I saw the shadow of my grandmother saying her prayers in our living room. But what did it mean to be an American? And why did my mother feel such an urgent need to remind me of it daily?

Years later, when my mother was ravaged by cancer at 55, she was confused for the last few days of her life and for the first time spoke candidly to me about her past. She relived whole days. But she didn’t even know who I was at one point I had to introduce myself as Susan.

She seemed frantic. “Oh, I have a daughter named Susan. I’ll help you.” Then she pulled me close and told me to cover up, that the Pasdaran were coming, that I should clean off my nail polish. She took a blanket off of the bed that we had brought into our family room and threw it at me with considerable strength.

“Hurry! Hurry!” she exclaimed. “They always take the young ones first!”

She grabbed a comforter and wrapped it around her head, which had only a few gray hairs remaining the chemotherapy had taken the rest.

I told her that we were living in America, that we were safe.

She scoffed at me, asking why we would ever leave Iran. It was, after all, home.

I shouldn’t have argued with her. We knew she could be just days from death. As it turned out, she had only hours left. She had left the hospital to die at home, in our care. But my anger got the better of me.

I threw down the blanket and yanked the comforter off of her. “We are safe! We live in America!”

She burrowed her head underneath a pillow. In her mind, she was still in Iran. But she was not bold, not defiant. She was terrified.

In the course of her five-year battle with cancer, I felt that we had arrived at our lowest point. The woman I had always revered was now quarantined to a bed in our family room, reliving a fear I’d been too young to share. All of my anger at the cancer, at our missed opportunities had come out in my shouted admonishments. But when I saw her there, her head underneath a pillow, I told her she was right. I covered myself in the blanket and rewrapped her in the comforter. I took a scarf from the hall closet and framed her face. And we sat there, in our air-conditioned family room in the suburbs of Baltimore, waiting for the Pasdaran.

My mother did not know where she was or who I was. But what most saddened me wasn’t that she had forgotten our home or me. I was less disturbed, in fact, by what she had forgotten than by what she had remembered. She had been brave all those years ago, yes, but she had hardly been without fear, then or now. And if her daily reminder was an affirmation of who we had become, or of who she imagined us to be, it also must have been a way to quash the fear that regularly bubbled up inside of her.

Suddenly she looked at me, asked if Nabi Khan was asleep, and slipped off her headscarf. She asked for a glass of tea as she heard the calls to prayer.

And I sat there, in our house on a street in Maryland, and I heard the calls with her as I slipped off my blanket and unbuttoned my shirt.

“Don’t be afraid,” she said. “If you lose your entire self, you’ll never get it back. Remind yourself of who you are.”

I broke up with Iran then and there.

My mother died that night. I suppose she would have said that the heat finally got to her.

In her eulogy, I grappled with what to say. My story of her had changed. I didn’t know the frightened woman I saw at the end, yet that must have been a large part of who she was. My mother had not left Iran behind. She had brought it with her, along with the fear. And now she was gone, and I had never asked her about any of it. Instead, I had created a myth. And I had repeated her affirmation “We live in America!” instead of asking a question. I had seen what I wanted to see in a woman I will never see again. In the end, I merely glimpsed the truth in a moment of confusion.

I am 30 years old now, and my mother would have been 63. I rarely talk about her, but I remember her every day. She is gone, yet I have brought her with me. I only wish I had known her better.