Imperial German

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

This article is about the German nation-state existing from 1871 until 1918. For other uses, see German Empire (disambiguation).

The German Empire or the Imperial State of Germany,[a][7][8][9][10] also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich,[11] the Kaiserreich, as well as simply Germany,[12] was the period of the German Reich[13] from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic.[14][15]

1880 census

Majority:

62.63% United Protestant

(Lutheran, Reformed)

Minorities:

35.89% Roman Catholic

1.24% Jewish

0.17% Other Christian

0.07% Other

Area and population not including colonial possessions

It was founded on 18 January 1871 when the south German states, except for Austria, joined the North German Confederation and the new constitution came into force, changing the name of the federal state to the German Empire and introducing the title of German Emperor for Wilhelm I, King of Prussia from the House of Hohenzollern.[16] Berlin remained its capital, and Bismarck, Minister-President of Prussia, became Chancellor, the head of government. As these events occurred, the Prussian-led North German Confederation and its southern German allies were still engaged in the Franco-Prussian War.

The German Empire consisted of 26 states, most of them ruled by royal families. They included four kingdoms, six grand duchies, five duchies (six before 1876), seven principalities, three free Hanseatic cities, and one imperial territory. Although Prussia was one of four kingdoms in the realm, it contained about two-thirds of Germany's population and territory. Prussian dominance had also been constitutionally established, as the King of Prussia was also the German Emperor.

After 1850, the states of Germany had rapidly become industrialized, with particular strengths in coal, iron (and later steel), chemicals, and railways. In 1871, Germany had a population of 41 million people; by 1913, this had increased to 68 million. A heavily rural collection of states in 1815, the now united Germany became predominantly urban.[17] During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire was an industrial, technological, and scientific giant, gaining more Nobel Prizes in science than any other country.[18] Between 1901 and 1918, the Germans won four Nobel Prizes in Medicine, six Prizes in Physics, seven Prizes in Chemistry, and three Prizes in Literature. By 1913, Germany was the largest economy in Continental Europe, surpassing the United Kingdom (excluding its Empire and Dominions), as well as the third-largest in the world, only behind the United States and the British Empire,[19] which were also its main economic rivals.

From 1871 to 1890, Otto von Bismarck's tenure as the first and to this day longest-serving Chancellor was marked by relative liberalism, but it became more conservative afterward. Broad reforms and the Kulturkampf marked his period in the office. Late in Bismarck's chancellorship and in spite of his earlier personal opposition, Germany became involved in colonialism. Claiming much of the leftover territory that was yet unclaimed in the Scramble for Africa, it managed to build the third-largest colonial empire at the time, after the British and the French ones.[20] As a colonial state, it sometimes clashed with the interests of other European powers, especially the British Empire. During its colonial expansion, the German Empire committed the Herero and Namaqua genocide.[21]

Germany became a great power, boasting a rapidly developing rail network, the world's strongest army,[22] and a fast-growing industrial base.[23] Starting very small in 1871, in a decade, the navy became second only to Britain's Royal Navy. After the removal of Otto von Bismarck by Wilhelm II in 1890, the empire embarked on Weltpolitik – a bellicose new course that ultimately contributed to the outbreak of World War I. In addition, Bismarck's successors were incapable of maintaining their predecessor's complex, shifting, and overlapping alliances which had kept Germany from being diplomatically isolated. This period was marked by various factors influencing the Emperor's decisions, which were often perceived as contradictory or unpredictable by the public. In 1879, the German Empire consolidated the Dual Alliance with Austria-Hungary, followed by the Triple Alliance with Italy in 1882. It also retained strong diplomatic ties to the Ottoman Empire. When the great crisis of 1914 arrived, Italy left the alliance and the Ottoman Empire formally allied with Germany.

In the First World War, German plans to capture Paris quickly in the autumn of 1914 failed. The war on the Western Front became a stalemate. The Allied naval blockade caused severe shortages of food. However, Imperial Germany had success on the Eastern Front; it occupied a large amount of territory to its east following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The German declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917 contributed to bringing the United States into the war.

The high command under Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff increasingly controlled the country, but in October 1918, after the failed Spring Offensive, the German armies were in retreat, allies Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire had collapsed, and Bulgaria had surrendered. The empire collapsed in the November 1918 Revolution with the abdications of its monarchs. This left a post-war federal republic and a devastated and unsatisfied populace, faced with post-war reparation costs of nearly 270 billion dollars,[24] all of which is considered a leading factor in the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazism.[25]

The German Confederation had been created by an act of the Congress of Vienna on 8 June 1815 as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, after being alluded to in Article 6 of the 1814 Treaty of Paris.[26]

The liberal Revolutions of 1848 were crushed after the alliance between the educated, well-off bourgeois liberals and the urban artisans broke down; Otto von Bismarck's pragmatic Realpolitik, which appealed to peasants as well as the traditional aristocracy, took its place.[27] Bismarck sought to extend Hohenzollern hegemony throughout the German states; to do so meant unification of the German states and the exclusion of Prussia's main German rival, Austria, from the subsequent German Empire. He envisioned a conservative, Prussian-dominated Germany. Three wars led to military successes and helped to persuade German people to do this: the Second Schleswig War against Denmark in 1864, the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, and the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–1871.

The German Confederation ended as a result of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 between the constituent Confederation entities of the Austrian Empire and its allies on one side and Prussia and its allies on the other. The war resulted in the partial replacement of the Confederation in 1867 by a North German Confederation, comprising the 22 states north of the Main River. The patriotic fervor generated by the Franco-Prussian War overwhelmed the remaining opposition to a unified Germany (aside from Austria) in the four states south of the Main, and during November 1870, they joined the North German Confederation by treaty.[28]

On 10 December 1870, the North German Confederation Reichstag renamed the Confederation the "German Empire" and gave the title of German Emperor to William I, the King of Prussia, as Bundespräsidium of the Confederation.[29] The new constitution (Constitution of the German Confederation) and the title Emperor came into effect on 1 January 1871. During the Siege of Paris on 18 January 1871, William accepted to be proclaimed Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.[30]

The second German Constitution, adopted by the Reichstag on 14 April 1871 and proclaimed by the Emperor on 16 April,[30] was substantially based upon Bismarck's North German Constitution. The political system remained the same. The empire had a parliament called the Reichstag, which was elected by universal male suffrage. However, the original constituencies drawn in 1871 were never redrawn to reflect the growth of urban areas. As a result, by the time of the great expansion of German cities in the 1890s and 1900s, rural areas were grossly over-represented.

The legislation also required the consent of the Bundesrat, the federal council of deputies from the 27 states. Executive power was vested in the emperor, or Kaiser, who was assisted by a Chancellor responsible only to him. The emperor was given extensive powers by the constitution. He alone appointed and dismissed the chancellor (so in practice, the emperor ruled the empire through the chancellor), was supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and final arbiter of all foreign affairs, and could also disband the Reichstag to call for new elections. Officially, the chancellor was a one-man cabinet and was responsible for the conduct of all state affairs; in practice, the State Secretaries (top bureaucratic officials in charge of such fields as finance, war, foreign affairs, etc.) functioned much like ministers in other monarchies. The Reichstag had the power to pass, amend, or reject bills and to initiate legislation. However, as mentioned above, in practice, the real power was vested in the emperor, who exercised it through his chancellor.

Although nominally a federal empire and league of equals, in practice, the empire was dominated by the largest and most powerful state, Prussia. Prussia stretched across the northern two-thirds of the new Reich and contained three-fifths of its population. The imperial crown was hereditary in the ruling house of Prussia, the House of Hohenzollern. With the exception of 1872–1873 and 1892–1894, the chancellor was always simultaneously the prime minister of Prussia. With 17 out of 58 votes in the Bundesrat, Berlin needed only a few votes from the smaller states to exercise effective control.

The other states retained their own governments but had only limited aspects of sovereignty. For example, both postage stamps and currency were issued for the empire as a whole. Coins through one mark were also minted in the name of the empire, while higher-valued pieces were issued by the states. However, these larger gold and silver issues were virtually commemorative coins and had limited circulation.

While the states issued their own decorations and some had their own armies, the military forces of the smaller ones were put under Prussian control. Those of the larger states, such as the Kingdoms of Bavaria and Saxony, were coordinated along Prussian principles and would, in wartime, be controlled by the federal government.

The evolution of the German Empire is somewhat in line with parallel developments in Italy, which became a united nation-state a decade earlier. Some key elements of the German Empire's authoritarian political structure were also the basis for conservative modernization in Imperial Japan under Meiji and the preservation of an authoritarian political structure under the tsars in the Russian Empire.

One factor in the social anatomy of these governments was the retention of a very substantial share in political power by the landed elite, the Junkers, resulting from the absence of a revolutionary breakthrough by the peasants in combination with urban areas.

Although authoritarian in many respects, the empire had some democratic features. Besides universal suffrage, it permitted the development of political parties. Bismarck intended to create a constitutional façade that would mask the continuation of authoritarian policies. In the process, he created a system with a serious flaw. There was a significant disparity between the Prussian and German electoral systems. Prussia used a highly restrictive three-class voting system in which the richest third of the population could choose 85% of the legislature, all but assuring a conservative majority. As mentioned above, the king and (with two exceptions) the prime minister of Prussia was also the emperor and chancellor of the empire – meaning that the same rulers had to seek majorities from legislatures elected from completely different franchises. Universal suffrage was significantly diluted by gross over-representation of rural areas from the 1890s onward. By the turn of the century, the urban-rural population balance was completely reversed from 1871; more than two-thirds of the empire's people lived in cities and towns.

Bismarck's domestic policies played an important role in forging the authoritarian political culture of the Kaiserreich. Less preoccupied with continental power politics following unification in 1871, Germany's semi-parliamentary government carried out a relatively smooth economic and political revolution from above that pushed them along the way towards becoming the world's leading industrial power of the time.

Bismarck's "revolutionary conservatism" was a conservative state-building strategy designed to make ordinary Germans—not just the Junker elite—more loyal to the throne and empire. According to Kees van Kersbergen and Barbara Vis, his strategy was:

granting social rights to enhance the integration of a hierarchical society, to forge a bond between workers and the state so as to strengthen the latter, to maintain traditional relations of authority between social and status groups, and to provide a countervailing power against the modernist forces of liberalism and socialism.[31]

Bismarck created the modern welfare state in Germany in the 1880s and enacted universal male suffrage in 1871.[32] He became a great hero to German conservatives, who erected many monuments to his memory and tried to emulate his policies.[33]

Bismarck's post-1871 foreign policy was conservative and sought to preserve the balance of power in Europe. British historian Eric Hobsbawm concludes that he "remained undisputed world champion at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after 1871, [devoting] himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace between the powers".[34] This was a departure from his adventurous foreign policy for Prussia, where he favored strength and expansion, punctuating this by saying, "The great question of the age are not settled by speeches and majority votes – this was the error of 1848–49 – but by iron and blood."[35]

Bismarck's chief concern was that France would plot revenge after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. As the French lacked the strength to defeat Germany by themselves, they sought an alliance with Russia, which would trap Germany between the two in a war (as would ultimately happen in 1914). Bismarck wanted to prevent this at all costs and maintain friendly relations with the Russians and thereby formed an alliance with them and Austria-Hungary, the Dreikaiserbund (League of Three Emperors), in 1881. The alliance was further cemented by a separate non-aggression pact with Russia called Reinsurance Treaty, which was signed in 1887.[36] During this period, individuals within the German military were advocating a preemptive strike against Russia, but Bismarck knew that such ideas were foolhardy. He once wrote that "the most brilliant victories would not avail against the Russian nation, because of its climate, its desert, and its frugality, and having but one frontier to defend", and because it would leave Germany with another bitter, resentful neighbor.

Meanwhile, the chancellor remained wary of any foreign policy developments that looked even remotely warlike. In 1886, he moved to stop an attempted sale of horses to France because they might be used for cavalry and also ordered an investigation into large Russian purchases of medicine from a German chemical works. Bismarck stubbornly refused to listen to Georg Herbert zu Munster (ambassador to France), who reported back that the French were not seeking a revanchist war and were desperate for peace at all costs.

Bismarck and most of his contemporaries were conservative-minded and focused their foreign policy attention on Germany's neighboring states. In 1914, 60% of German foreign investment was in Europe, as opposed to just 5% of British investment. Most of the money went to developing nations such as Russia that lacked the capital or technical knowledge to industrialize on their own. The construction of the Baghdad Railway, financed by German banks, was designed to eventually connect Germany with the Ottoman Empire and the Persian Gulf, but it also collided with British and Russian geopolitical interests. Conflict over the Baghdad Railway was resolved in June 1914.

Many consider Bismarck's foreign policy as a coherent system and partly responsible for the preservation of Europe's stability.[37] It was also marked by the need to balance circumspect defensiveness and the desire to be free from the constraints of its position as a major European power.[37] Bismarck's successors did not pursue his foreign policy legacy. For instance, Kaiser Wilhelm II, who dismissed the chancellor in 1890, let the treaty with Russia lapse in favor of Germany's alliance with Austria, which finally led to a stronger coalition-building between Russia and France.[36]

Bismarck secured a number of German colonial possessions during the 1880s in Africa and the Pacific, but he never considered an overseas colonial empire valuable due to fierce resistance to German colonial rule from the natives. Thus, Germany's colonies remained badly undeveloped.[38] However, they excited the interest of the religious-minded, who supported an extensive network of missionaries.

Germans had dreamed of colonial imperialism since 1848.[39] Bismarck began the process, and by 1884 had acquired German New Guinea.[40] By the 1890s, German colonial expansion in Asia and the Pacific (Kiauchau in China, Tientsin in China, the Marianas, the Caroline Islands, Samoa) led to frictions with the UK, Russia, Japan, and the US. The largest colonial enterprises were in Africa,[41] where the Herero Wars in what is now Namibia in 1906–1907 resulted in the Herero and Namaqua genocide.[42]

By 1900, Germany became the largest economy in continental Europe and the third-largest in the world behind the United States and the British Empire, which were also its main economic rivals. Throughout its existence, it experienced economic growth and modernization led by heavy industry. In 1871, it had a largely rural population of 41 million, while by 1913, this had increased to a predominantly urban population of 68 million.

For 30 years, Germany struggled against Britain to be Europe's leading industrial power. Representative of Germany's industry was the steel giant Krupp, whose first factory was built in Essen. By 1902, the factory alone became "A great city with its own streets, its own police force, fire department and traffic laws. There are 150 kilometers

Caprice Creampie

Ebony Blowjob Pov

Dick Name

Hardcore Hot Fucking Sex

Celebrity Ero Video

German Empire - Wikipedia

Imperial Germans - Wikipedia

Imperial Germany

Imperial Germany - Weimar Republic

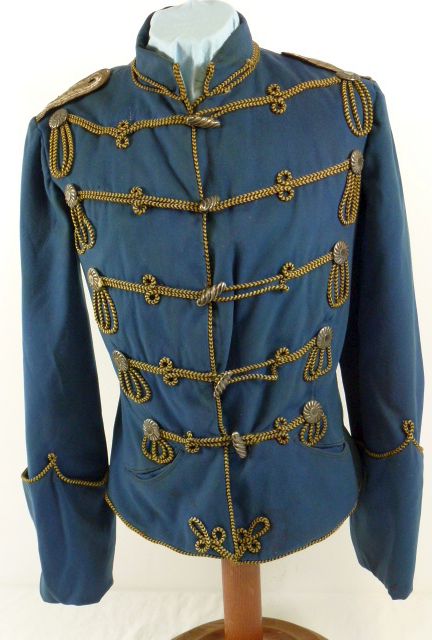

IMPERIAL GERMAN 1914-1918 - germanmilitaria.com

Imperial German Navy - Wikipedia

German Army (German Empire) - Wikipedia

Imperial German

.svg/1200px-War_Ensign_of_Germany_(1903%e2%80%931919).svg.png)