How to progress in mountaineering?

MCS AlexClimbMountaineering school MCS AlexClimb

The text below has no universal general suggestions as you might expect. The ordinal article in Russian refers mostly to the very special phenomenon in Russian mountaineering which we call "chase for checkbox". The English version of the text can be interesting not as a set of practical climbing advices but mostly as a reflection of strange and contorted form which can take the usual thing under influence of lame ideology.

Often people who have received their first impressions in the mountains with us, and are eager to climb more difficult peaks, ask a question - what to do next?

The two main paths along which, (being in Russian reality), you could set off towards your close acquaintance with the mountain peaks are either the conservatively formal path of our soviet grandfathers or the faster but more thorny modern version of mountaineering evolution.

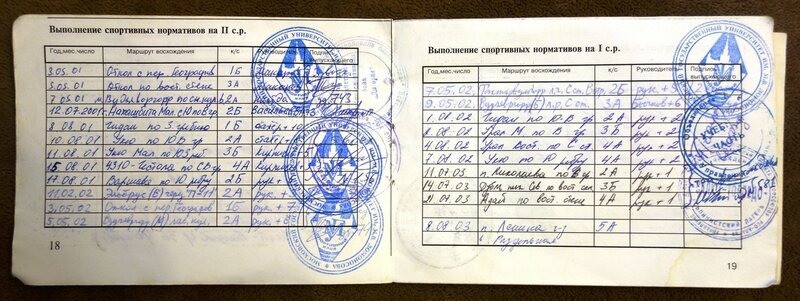

The first option is the old Soviet way, genetically close to anyone who was born by Soviet parents - a formal journey through the ranks and filling out the ticks in the box in the “Climber’s Book”.

The second way, more modern and not related to the history of a particular country, is dictated by global trends in the development of the outdoor industry. It does not have the excess of formalities that is characteristic of the first approach.

Total commercialization, which adherents of the “old Soviet school” do not like, in practice represents a wide range of opportunities in choosing climbing goals and ways to achieve them, the availability of high-quality service and professional rescue support.

In order to follow this path, first you just need to choose a goal - a complex, beautiful and high dream mountain. Then, over time, in various ways, build the set of necessary skills to realize this dream.

What is good or bad about each of these two approaches?

The first, “Soviet” option used to be good because it was based on an old, time-tested training methodology - step-by-step completion of training modules, a gradual increase in the complexity of the climbing routes.

The main disadvantage of the “Soviet system” in mountaineering is that it no longer exists. In addition, with such an approach, you may have incorrect motivation from the very beginning, which is unacceptable in mountaineering - formalism.

In the Soviet system of mountaineering, a bonus to climbing was receiving ranks and “papers", getting higher on the hierarchical ladder, which in turn provided a number of advantages within Soviet society and the mighty in the Soviet Era VCSPS system - (All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions).

Today, this system does not exist, and what is left of it in mountaineering has degraded to the point of "chase for checkbox" - when a person becomes interested not so much in the object of climbing - the mountain, but in the formal mark that he will receive for this ascent.

In modern Russian reality, this approach has become a definite commercial trend and finds its audience among conservative clients.

In Russia a few old mountain camps of varying degrees of preservation operate on the principle of stamping standard forms, operating with the seals and ticks - using the old Soviet system of mountaineering training as nothing more than a trade brand.

However, I repeat - the system that gave rise to this phenomenon no longer exists. There is neither the ideology that underlay the Soviet mountaineering, nor a powerful school of instructors brought up on this ideology, capable of passing on an array of their experience to the beginners.

In fact, there is no more valuable experience left - the remaining witnesses and participants of the glorious climbing ascents of the Soviet times are already at that age when it is better to share memories than experience.

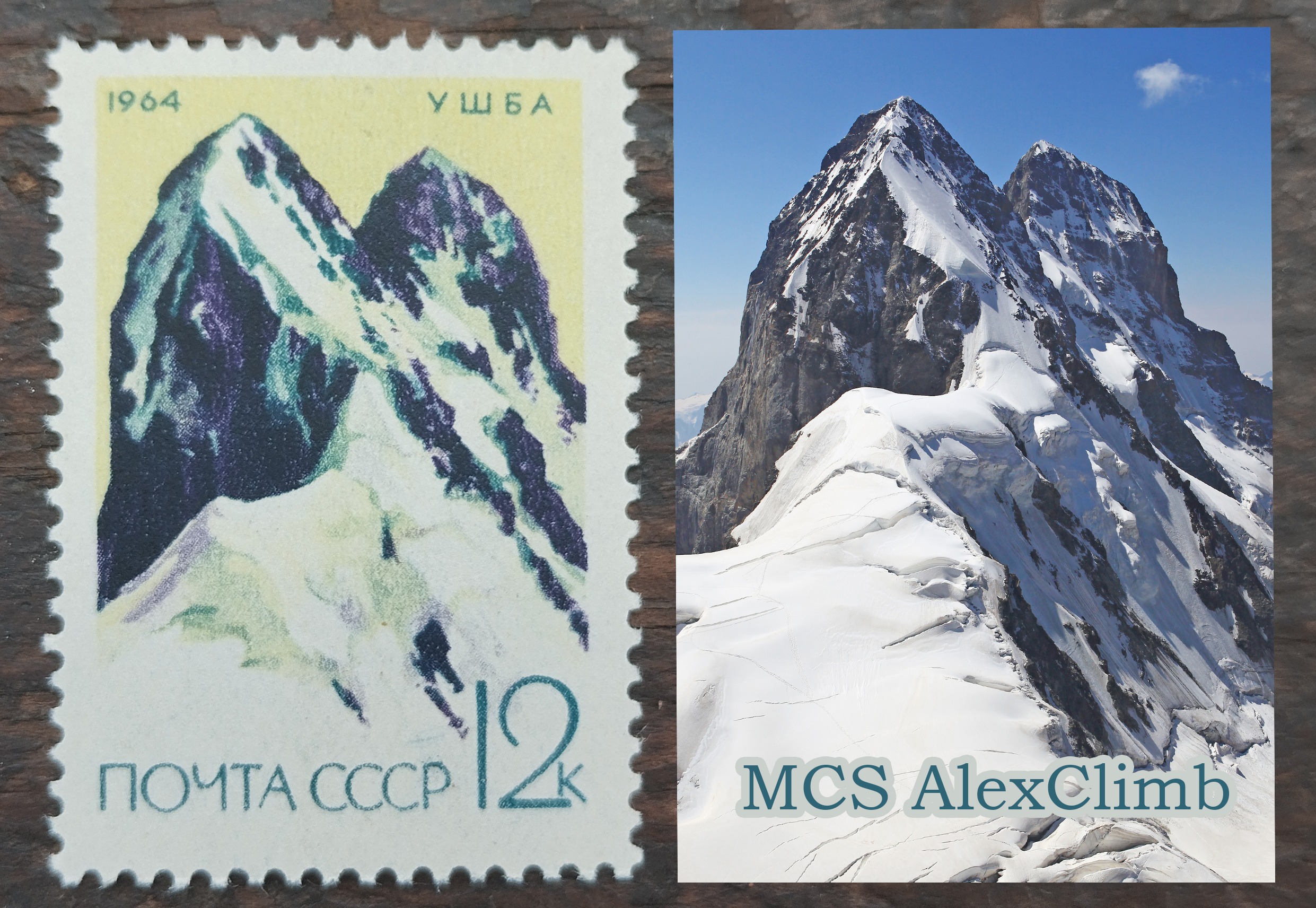

There are two mountains, very similar in their character, altitude, charisma and fame. Despite all the similarities, both mountains have a completely different history of relationships with humans. Mount Ushba used to be a classic of Soviet mountaineering.

All the most striking and complex sporting achievements in post-war Soviet mountaineering in the Caucasus were in one way or another connected with most famous mountain of Caucasus - Mount Ushba.

This mountain was the asset of every famous Soviet climber and was a kind of “maturity test”. As sport mountaineering developed in the USSR, the classic route to Mount Ushba was gradually becoming lower in category.

That was done partly intentionally, since Mount Ushba occupied an exceptional place in the Soviet classification system of climbing routes. The uniqueness of Mount Ushba was that the name of the mountain prevailed over its declared technical category.

The classic Mount Ushba route of the 4th category was inaccessible to climbers who formally had the right to access to the routes of this category, but did not have experience in other ascents of 4th grade.

In accordance with the unspoken rule, Mount Ushba could not be the first “4th” in the set of sports climbs!

Using this example, I can say that already in the Soviet times, Mount Ushba divided people according to their approach to the issue of motivation in mountaineering.

Those who needed Mount Ushba went to Mount Ushba. The route to this mountain was deliberately omitted from the categories in order to “weed out” those who did not need the Summit, but simply “a tick in the box.”

For formal climbers there was the opportunity to choose routes that did not require such concentration of effort, risk and time spent as for climbing Mount Ushba. Many routes of the 4th category in the Elbrus region could be climbed in 1-2 days without much hassle, high risk or excessive effort.

Agree, if you need just some route of 4th category, why to spend a week climbing Mount Ushba, with an unpredictable result - Mount Ushba can just "deny your access"?

One could comfortably go in one day from camp to camp to the rock tower of the peak MNR (Mongolian People's Republic) and get the desired mark in the column “4a” of his Climber Book.

Today, access to the routes of Mount Ushba is possible only from the south, from the Georgian side. From the north side (which is Russian), especially from the Shkheldinsky Gorge, the Russian authorities introduced a complete ban on the climbing to all the mountain summits of the Main Caucasus, including Mount Ushba.

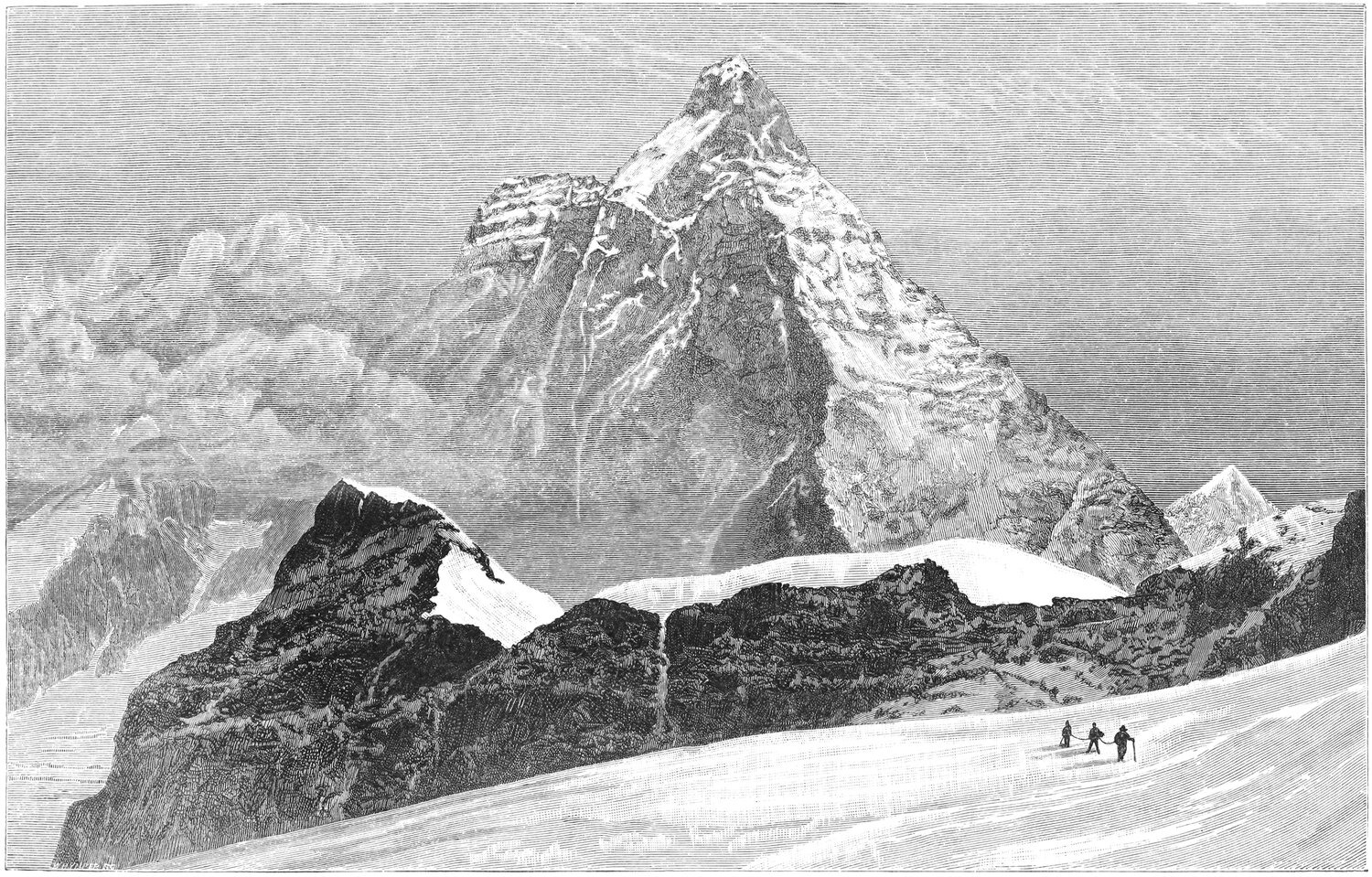

My second example will be Matterhorn - the legendary peak on the border of Switzerland and Italy, the European birthplace of technical mountaineering.

Despite the fact that the Matterhorn retained its status as an “impregnable mountain” longer than any other alpine peak, starting from the end of the 19th century it began to gain its popularity as commercial climbing route of the highest level of difficulty.

The first two ascents of the Matterhorn left the most striking mark in the history of modern mountaineering. The ascents of Carrel from Italy and Whymper from Switzerland were an amazing example of determination and fortitude.

These difficult first ascents of the two most popular routes to the Matterhorn today were completed in conditions of total lack of equipment, infrastructure, communications and safety service.

Now, climbing Matterhorn along a route equipped with shelters fixed ropes and stationary ladders, using all the “benefits of civilization” - modern clothing, high quality equipment - it is difficult to even imagine the trials that befell to the pioneers.

Despite the boundary location and high difficulty of Matterhorn climbing routes, never in the history has there been an attempt to limit access to this mountain in any way.

Climbing the Matterhorn has never been formalized by issuing any certificates any special references. No one was given any official ranks for climbing the Matterhorn either - alpine mountaineering did not suffer from this in any way.

Although the border between Italy and Switzerland runs right along the summit, the idea of issuing border passes to the Matterhorn has never occurred to anyone - in a civilized society such a pathology goes beyond the limits of possible absurdity.

Anyone always can challenge the mountain - this is the normal right of any normal person - control in this case should be exercised only by common sense.

It is significant that in terms of ensuring safety, such a control mechanism turned out to be more effective than the Russian “formal method”.

The number of accidents in the highly popular for climbers region of Cervinia (It) / Zermatt (Ch), where numerous iconic peaks and trekking routes are located, is significantly lower than the accident rate in areas “regulated” by the old Soviet bureaucratic system.

Climbing the Matterhorn cannot be classified according to the Russian classification system. Two classic routes - from Italy (Leone) and Switzerland (Hörnli) are equipped in accordance with the safety standards of commercial mountaineering.

Many difficult pitches became significantly easier due to the presence of stationary shelters, belay stations, ladders and fixed ropes.

The topic of this article caused a storm of indignation among the instructors of the old Soviet school, as well as fans badges and checkmarks.

The only clear objection was that commerce in the mountains vulgarizes the “idea of mountaineering.” However, no one could explain the essence of this idea. Whatever this essence is, a counter question arises - do formalization and bureaucracy not vulgarize anything?

Two my examples speak eloquently: developed, efficient and safe mountain resorts in the Alps, covered by a network of comfortable shelters, with modern and effective rescue services, and ample opportunities for all types of mountain recreation. And very importantly - the lowest accident rate in the world.

In contrast: collapsed old Soviet alpine camps, idiotic climbing bans, poor, unqualified rescue services moonlighting on the tourist routes.

However, in many respects besides mountaineering: in Russia we have a strange national peculiarity - we love to be proud of the achievements of our ancestors against the backdrop of the ruins into which we have turned these achievements.

But from the fact that 50 years ago our ancestors made ascents that aroused respectful awe among the strongest climbers in the West, we inherited the habit of “chasing for checkboxes” and hating those who think differently.

Author of the story and photographs - Alex Trubachev

Your professional international mountain guide and climbing coach

MCS EDIT 2024