How Ilahita Got Big

In the mid-20th century, anthropologists working in the remote Sepik region of New Guinea noticed that villages rarely exceeded about 300 people, of whom about 80 were men. The 300 were divided into a handful of patrilineal clans. When communities exceeded this size, cracks inevitably began to appear, and eventually social ruptures occurred along clan lines. Larger villages fractured into feuding hamlets and pushed away from each other to reduce conflicts. Though these explosions were typically sparked by disagreements about marriage, adultery, or witchcraft-induced deaths, they often ignited a pyre of nagging grievances.3

The relatively small size of these communities is puzzling, since warfare and raiding posed a persistent and deadly threat. Because different villages had roughly the same weapons and military tactics, greater numbers could make all the difference. Larger communities were safer and more secure, so people had life-and-death incentives to “make it work” and grow larger. Nevertheless, there seemed to be an invisible ceiling on the scale of cooperation.4

There was one striking exception to the “300 rule”: an Arapesh community called Ilahita had integrated 39 clans into a population of over 2,500 people. Ilahita’s existence put to rest simple explanations for the 300 rule based on ecological or economic constraints, since Ilahita’s environment and technology were indistinguishable from those of surrounding communities. As elsewhere, villagers used stone tools and digging sticks to grow yams, taro, and sago (the starchy pith of palms) and used nets to hunt pigs, wallabies, and cassowaries.5

In the late 1960s, the anthropologist Donald Tuzin set off to investigate. His questions were simple: How was Ilahita able to scale up? Why didn’t this community break up like all the others?

Tuzin’s detailed study reveals how Ilahita’s particular package of social norms and beliefs about rituals and gods built emotional bridges across clans, fostered internal harmony, and nurtured solidarity across the entire village. This cultural package stitched Ilahita’s clans and hamlets into a unified whole, one capable of larger-scale cooperation and communal defense. The nexus of Ilahita’s social norms centered on its version of a ritual cult called the Tambaran. The Tambaran had been adopted by a number of Sepik groups over several generations, but as you’ll see, Ilahita’s version was unique.

Like most communities in the region, Ilahita was organized into patrilineal clans, which usually consisted of several related lineages. Clan members saw themselves as connected by descent through their fathers from an ancestor god. Each clan jointly owned land and shared responsibility for each other’s actions. Marriages were arranged, often for infant daughters or sisters, and wives moved to live in their husbands’ hamlets (patrilocal residence). Men could marry polygynously, so older and more prestigious men typically married additional, younger wives.6

Unlike other Sepik communities, however, Ilahita’s clans and hamlets were crosscut by a complex organization of eight paired ritual groups. As part of the Tambaran, these groups organized all rituals, along with much of daily life. The highest-level pairing divided the village into two parts, which we’ll call ritual groups A and B. Groups A and B were each then divided in half; label these halves 1 and 2. Crucially, these second-tier divisions crosscut the first-tier ritual groups, so at this point, we have subgroups A1, B1, A2, and B2. Hence, people in A2 have a link with those in B2: both are in subgroup 2, and social norms dictated that they would sometimes need to work together on ritual tasks. Each subgroup was then further divided into two sub-subgroups that crosscut the higher levels. This continued down for five more tiers.

These ritual groups possessed a variety of reciprocal responsibilities that together threaded a network of mutual obligations that crisscrossed the entire village. For example, while every household raised pigs, it was considered disgusting to eat one’s own pigs. People felt that eating one’s own pigs would be like eating one’s own children. Instead, members of one ritual group (e.g., group A) gave pigs to the other half (group B). This imbued even simple activities like pig rearing with sacred meaning while at the same time threading greater economic interdependence through the population. At communal ceremonies, ritual groups alternated administering initiation rites to the men of their paired ritual group. Ilahita males had to pass through five different initiation rites. Only by completing these rites could boys become men, earn the privilege to marry, acquire secret ritual knowledge, and gain political power. However, sacred beliefs required that these rites be performed by the opposite ritual group. So, to become a respected man and ascend the ritual (and political) hierarchy, all males were dependent on those in other Ilahita clans.

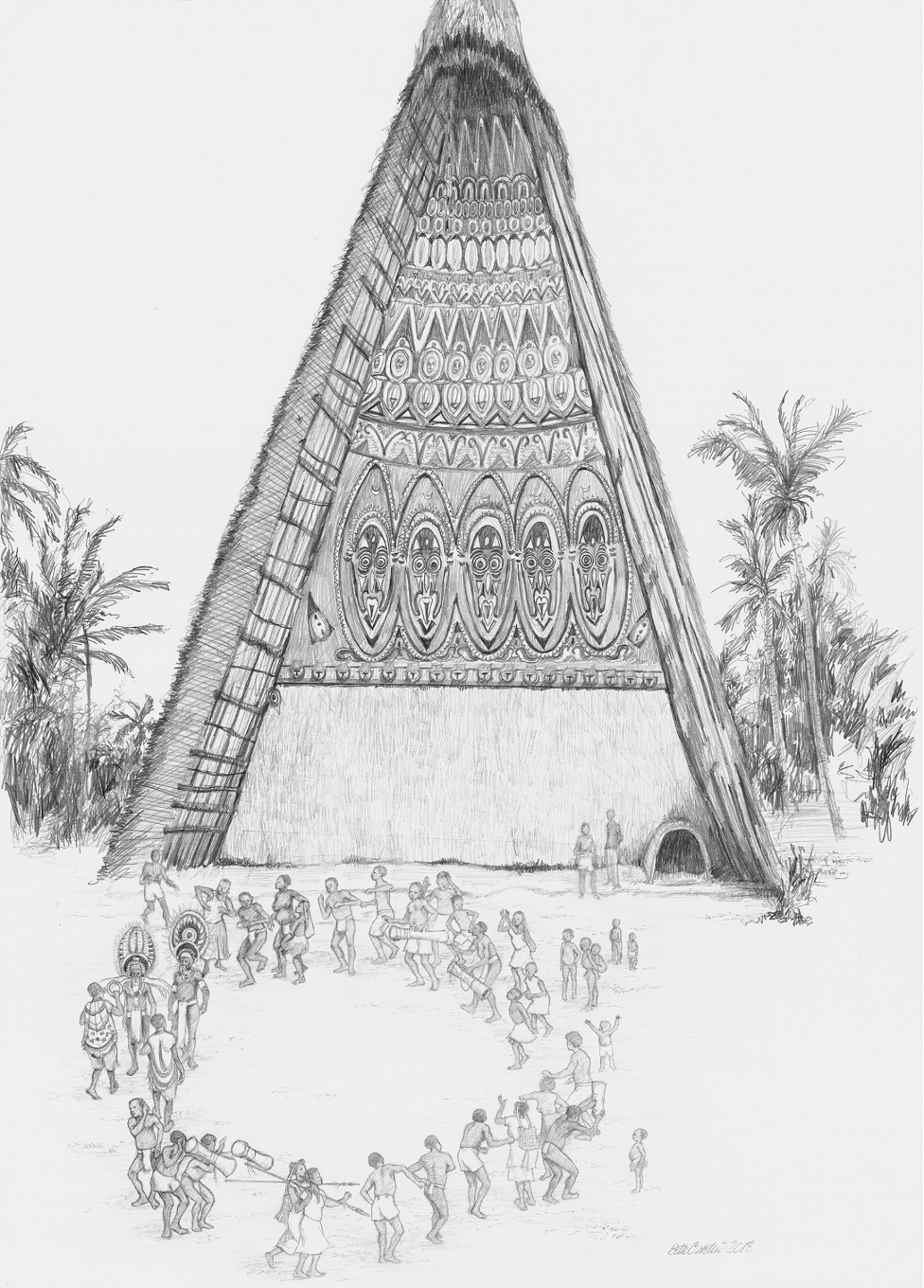

Alongside these ritual obligations, Tambaran norms also called for the entire village to work together in large community projects. Vastly larger than other structures in the community, the spirit house in Figure 3.1 was one such project.

Consistent with much psychological research on rituals, Tuzin’s ethnography suggests that these mutual obligations and joint projects built emotional bonds among individuals and—most importantly in this context—across clans and hamlets. Much of this effect probably comes from tapping our evolved interdependence psychology. Interestingly, this isn’t “real” interdependence, as in modern societies, where none of us would survive without massive economic exchange, but a kind of culturally constructed interdependence. Clans alone, as they did elsewhere in the Sepik, could have been economically independent, growing yams, raising pigs, and conducting initiation rites all on their own. However, Ilahita’s Tambaran gods forbade such activities, and thus imposed a kind of “artificial” interdependence.7

Ilahita’s Tambaran also incorporated psychologically potent communal rituals. Along with joint music-making and synchronous dance, the Tambaran gods demanded what anthropologists callrites of terror. Often administered to adolescent boys, these rites put participants through pain, isolation, deprivation, and frightening experiences involving darkness, masked figures, and unnatural sounds. Here again, new psychological evidence confirms old anthropological hunches: experiencing terror together forges powerful memories and deep emotional connections that bind participants for a lifetime. This creates the “band of brothers” phenomenon that emerges among soldiers who have faced combat together. In this institutionalized form, however, such rituals draw together young males from different clans and actively induce these binding psychological effects—thereby forging enduring interpersonal bonds in each new generation.8

Though rites of terror have evolved independently in small-scale societies all over the world, Ilahita had a particularly intense package, with five initiation levels. The sequence began at around age five. After being taken from their mothers, boys were introduced to the high-pageantry world of all-male rites by having stinging nettles rubbed on their scrota. They were then warned never to reveal anything about these special rituals to women, under pain of death. At around age nine, their second initiation culminated in the slashing of their penises with a bamboo razor. During adolescence, initiates were isolated in a secret village for months and prohibited from eating several desirable foods. In the most senior rites, initiates had to hunt down and kill men from enemy communities in order to “feed” the Tambaran gods. These emotionally intense rites further galvanized the bonds holding Ilahita’s clans and hamlets together.10

This social and ritual system was infused with a powerful set of supernatural beliefs. Unlike their ancestor gods, who presided narrowly over particular clans, the Tambaran gods governed the entire community—they were village-level gods. Villagers believed that their community’s prosperity and prestige derived from the proper performance of the Tambaran rituals, because those rituals satisfied the Tambaran gods, who, in return, blessed their community with harmony, security, and success. When village amity waned, the elders assumed that people hadn’t been diligently performing the rituals properly and would call for supplemental rites to better satiate the gods. Although the elders had the causality wrong, performing additional rituals still would have had the desired psychological effect—mending and solidifying social harmony. By Tuzin’s account, this was indeed what happened when such special rituals were performed.

The Tambaran gods also fostered greater harmony through their perceived willingness to punish villagers. Unlike the broad-based punishing powers of the powerful and moralizing gods found in today’s world religions, the Tambaran gods were only believed to punish people for inadequate ritual performances. This supernatural punishment, however, would have helped guarantee that villagers conscientiously attended to the rituals, which is crucial since the rituals were doing important social-psychological work in bonding the community.

The Tambaran gods’ supernatural punishment may have also suppressed sorcery accusations and their associated cycles of violence. In New Guinea, as in many societies, people don’t see most deaths as accidental. Deaths that WEIRD people would consider as due to “natural causes” (e.g., infections or snakebites) are often perceived as caused by sorcery—i.e., murder by magic. An unexpected death, especially of someone in their prime, often provoked sorcery accusations, and sometimes led to revenge-driven slugfests between clans that could persist over years or even generations. After the Tambaran arrived in Ilahita, many of the deaths that villagers would have previously perceived as sorcery-induced were instead attributed to the anger of the Tambaran gods, who were believed to strike people down for failing in their ritual obligations. This possibility reoriented people’s suspicions away from their fellow villagers and toward the gods. These new supernatural beliefs thus short-circuited one of the prime fuses that would have otherwise led to community disintegration.11

Overall, the Tambaran was a complex institution that integrated new organizational norms (ritual groups), routine practices (e.g., raising pigs), potent initiation rites, and beliefs about supernatural punishment in a manner that restructured social life. These cultural elements tapped into several aspects of innate human psychology in ways that strengthened and sustained the emotional bonds among Ilahita’s clans. This enabled Ilahita to maintain a large community of many clans while other villages fractured and fell apart.

But, where did Ilahita’s Tambaran come from?

Let’s start with where it didn’t come from. Tuzin’s investigation reveals that the Tambaran wasn’t designed by any individual or any group. When Tuzin showed the elders how elegantly the Tambaran partitioned and integrated their community, they were as surprised as he was. They’d followed simple prohibitions, prescriptions, and rules of thumb about people’s roles, responsibilities, and obligations that created the system without anyone having a global understanding of how it all fit together. As in nearly all societies, individuals don’t consciously design the most important elements of their institutions and certainly don’t understand how or why they work.12

Instead, the Tambaran evolved over generations, morphing into diverse forms as it diffused across the Sepik. Ilahita just happened to end up with the best working version. Here’s the story that Tuzin pieced together:

In the mid-19th century, a Sepik tribe called the Abelam began aggressively expanding, seizing territory, and sending families and clans fleeing from their villages. Because they were more militarily successful than other groups, it was widely assumed that the Abelam had developed some new rituals that had permitted them to tap into powerful supernatural forces. Around 1870, Ilahita’s elders learned about the Tambaran from some of these refugees. It was decided that Ilahita’s best chance to withstand the coming onslaught from the Abelam was to copy the Tambaran from them—to fight fire with fire. Piecing together the refugees’ descriptions of the Tambaran, Ilahita assembled its own version.

Crucially, while Ilahita’s Tambaran did end up resembling that of the Abelam, a number of consequential “copying errors” were inadvertently introduced during the reconstruction. There were three key errors. First, Ilahita “misfit” the ritual group organization to their clan structures, accidentally producing a greater degree of crosscutting and integration. The Ilahita system, for example, put brothers in different ritual groups and partitioned clans. The Abelam version, by contrast, left brothers together and clans fully encompassed within single ritual groups. Second, a mis- understanding created bigger, more powerful Tambaran gods. The Tambaran gods have specific names. Among the Abelam, they are the names of their clans’ ancestor gods—so their Tambaran gods are just an ensemble of their ancestor gods. In Ilahita, the clans each already had their own ancestor gods. Not recognizing the divine Abelam names, Ilahita’s elders superimposed the Tambaran gods over their own clan gods, effectively creating village-level gods where none had previously existed. Although it might seem odd to measure the size of a god, this copying error swelled the Tambaran gods by a factor of 39—instead of sitting at the apex of only one clan, these gods ascended to preside over 39 clans. Finally, Ilahita’s elders simply appended the Abelam’s four initiation rites to their own single Arapesh rite, giving them five initiation levels. By pushing up the age at which senior men passed out of the Tambaran system, this change effectively made the most powerful elders a decade older, and hopefully wiser, than among the Abelam.13

With this retrofit of the Tambaran, Ilahita halted the relentless advance of the Abelam and expanded its own territory. Ilahita swelled further over the subsequent decades as refugees from other villages flooded in. Despite their lack of kinship or marital ties to Ilahita’s clans, immigrants were woven into the community through the Tambaran ritual system.