How German Schools Teach Constitution

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

We use cookies to improve our service for you. You can find more information in our data protection declaration.

Germany's private schools are violating the constitution by picking students according to their parents' wealth, a new study has found. The result is increasing social segregation and elitism, the authors say.

German state governments are allowing schools to disregard an article of the country's constitution designed to ensure that a mixture of social classes are able to attend private schools, according to a new study by the Berlin Social Science Center (WZB).

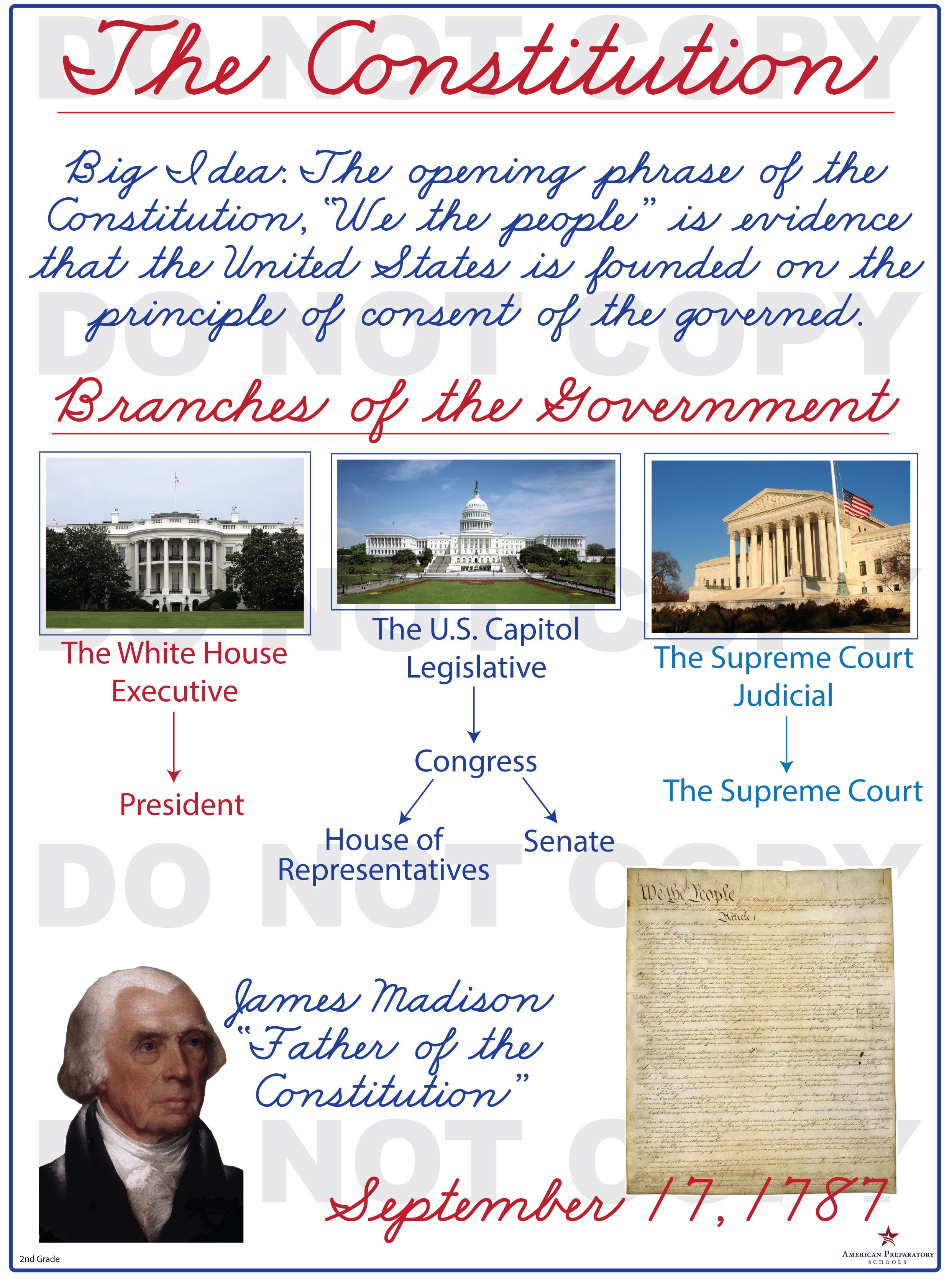

Article 7, Paragraph 4 of the "Basic Law" guarantees the right to establish private schools as an alternative to state schools - but only subject to their approval by state governments, who are responsible for education in Germany. "Such approval shall be given when private schools are not inferior to the state schools in terms of their educational aims, their facilities, or the professional training of their teaching staff, and when segregation of pupils according to the means of their parents will not be encouraged thereby," the paragraph reads.

But the WZB study found that most German state governments do not enforce that principle, and some don't even have any regulations in place with which to do so.

The two authors of the report, law professor Michael Wrase and sociologist Marcel Helbig, identified nine basic laws that would have to be in place to enforce the German constitution as it is written, including a cap on school fees or guarantees that children from low-income families do not have to pay them.

They found that none of Germany's 16 states implement all nine of these principles, while two, Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia, had five of them in place. Two other states, Thuringia and Bremen, had no regulations at all. On top of that, no state formally assesses private schools' intake strategy.

Although many states impose some kind of cap on school fees - in 2010, a court in Stuttgart put the limit at 150 euros ($160) a month - private schools have found myriad ways to get round them, even if they have a sliding scale for basic fees based on parents' income.

The Berlin Cosmopolitan School, for instance, charges extra for bilingual classes, special courses and extracurricular activities, while the Metropolitan School in Berlin includes extra charges for lunch (for all students), "digital media fees," and class trips and external exams.

According to Wrase, well-off parents can easily end up paying up to 800 euros a month for their child's schooling. "It's obvious that if I have one child that brings in 800 euros a month and another that brings only 250 euros, then for economic reasons I'll probably take the child coming from a richer home," said Wrase.

Germany is fairly unique among Western countries in its aversion to elite high schools - the Weimar constitution of 1919 established that schools should be under state oversight and open to all children - although schools run by religious institutions were protected - something which found its way into the Federal Republic's Basic Law in 1949. Ever since, Germany has not had elite schools like those in the UK or the US.

Private schools in Germany still get the majority of their budget from the state, which means they can't claim complete independence, but also that they have a significantly higher budget that allows them to offer better services - at a cost to the taxpayer. But according to the letter of the German law, even children of low income parents should have access to them - though the WZB shows that they do not.

"As a consequence, it has become clear that schools in any given region are getting more and more unequal," said Wrase. "This is especially true in larger cities, where you have state schools in more difficult circumstances with more difficult children - where parents are more inclined to send their children to a fancy private school."

Some state governments - including Baden-Württemberg and Berlin - have indicated their intention to reassess their oversight of private schools in the wake of the WZB report. The German association of private schools (VDP) did not respond to requests for comment.

Education in Germany is primarily the responsibility of individual German states (Länder), with the federal government playing a minor role. Optional Kindergarten (nursery school) education is provided for all children between one and six years old, after which school attendance is compulsory.[1] Overall, Germany is one of the best performing OECD countries in reading literacy, mathematics and sciences with the average student scoring 515 in the PISA Assessment Test, well above the OECD average of 497 points.[2] Germany has a less competitive system, leading to low rates of bullying and students having a weak fear of failure but a high level of self-confidence and general happiness compared to other OECD countries like South Korea.[3] Additionally, Germany has one of the largest percentage of top performers in reading among socio-economically advantaged students, ranking 3rd out of 76 OECD countries. This leads to Germany having one of the highest-educated labour forces among OECD countries.[4][5]

The schooling system varies throughout Germany because each state (Land) decides its own educational policies. Most children, however, first attend Grundschule (primary or elementary school) for 4 years from the age of 6 to 9. Germany's secondary education is separated into two parts, lower and upper. Lower-secondary education in Germany is meant to teach individuals basic general education and gets them ready to enter upper-secondary education. In the upper secondary level Germany has a vast variety of vocational programs. German secondary education includes five types of school. The Gymnasium is designed to prepare pupils for higher education and finishes with the final examination Abitur, after grade 13.

From 2005 to 2018 a school reform known as G8 provided the Abitur in 8 school years. The reform failed due to high demands on learning levels for the children and were turned to G9 in 2019. Only a few Gymnasiums stay with the G8 model. Children usually attend Gymnasium from 10 to 18 years. The Realschule has a broader range of emphasis for intermediate pupils and finishes with the final examination Mittlere Reife, after grade 10; the Hauptschule prepares pupils for vocational education and finishes with the final examination Hauptschulabschluss, after grade 9 and the Realschulabschluss after grade 10. There are two types of grade 10: one is the higher level called type 10b and the lower level is called type 10a; only the higher-level type 10b can lead to the Realschule and this finishes with the final examination Mittlere Reife after grade 10b. This new path of achieving the Realschulabschluss at a vocationally-oriented secondary school was changed by the statutory school regulations in 1981—with a one-year qualifying period. During the one-year qualifying period of the change to the new regulations, pupils could continue with class 10 to fulfil the statutory period of education. After 1982, the new path was compulsory, as explained above.

The format of secondary vocational education is designed for individuals to learn advanced skills for a specific profession. According to Clean Energy Wire, a news service covering the country's energy transition, "Most of Germany's highly-skilled workforce has gone through the dual system of vocational education and training (VET)".[6] Many Germans participate in the V.E.T. programs. These programs are partnered with about 430,000 companies, and about 80 percent of those companies hire individuals from those apprenticeship programs to get a full-time job.[6] This educational system is very encouraging to young individuals because they are able to actively see the fruits of their labor. The skills gained through these programs are easily transferable and once a company commits to an employee from one of these vocational schools, they have a commitment to each other.[7] Germany's V.E.T. programs prove that a college degree is not necessary for a good job and that training individuals for specific jobs could be successful as well.[8]

Other than this, there is the Gesamtschule, which combines the Hauptschule, Realschule and Gymnasium. There are also Förder- or Sonderschulen, schools for students with special educational needs. One in 21 pupils attends a Förderschule.[9][10] Nevertheless, the Förder- or Sonderschulen can also lead, in special circumstances, to a Hauptschulabschluss of both type 10a or type 10b, the latter of which is the Realschulabschluss. The amount of extracurricular activity is determined individually by each school and varies greatly. With the 2015 school reform the German government has tried to push more of those pupils into other schools, which is known as Inklusion.

Many of Germany's hundred or so institutions of higher learning charge little or no tuition by international comparison.[11] Students usually must prove through examinations that they are qualified.

To enter university, students are, as a rule, required to have passed the Abitur examination; since 2009, however, those with a Meisterbrief (master craftsman's diploma) have also been able to apply.[12][13] Those wishing to attend a university of applied sciences (Fachhochschule) must, as a rule, have Abitur, Fachhochschulreife, or a Meisterbrief. If lacking those qualifications, pupils are eligible to enter a university or university of applied sciences if they can present additional proof that they will be able to keep up with their fellow students through a Begabtenprüfung or Hochbegabtenstudium (which is a test confirming excellence and above average intellectual ability).

A special system of apprenticeship called Duale Ausbildung (the dual education system) allows pupils in vocational courses to do in-service training in a company as well as at a state school.[10]

Historically, Lutheranism had a strong influence on German culture, including its education. Martin Luther advocated compulsory schooling so that all people would independently be able to read and interpret the Bible. This concept became a model for schools throughout Germany. German public schools generally have religious education provided by the churches in cooperation with the state ever since.

During the 18th century, the Kingdom of Prussia was among the first countries in the world to introduce free and generally compulsory primary education, consisting of an eight-year course of basic education,Volksschule. It provided not only the skills needed in an early industrialized world (reading, writing, and arithmetic) but also a strict education in ethics, duty, discipline and obedience. Children of affluent parents often went on to attend preparatory private schools for an additional four years, but the general population had virtually no access to secondary education and universities.

In 1810, during the Napoleonic Wars, Prussia introduced state certification requirements for teachers, which significantly raised the standard of teaching. The final examination, Abitur, was introduced in 1788, implemented in all Prussian secondary schools by 1812 and extended to all of Germany in 1871. The state also established teacher training colleges for prospective teachers in the common or elementary grades.

When the German Empire was formed in 1871, the school system became more centralized. In 1872, Prussia recognized the first separate secondary schools for females. As learned professions demanded well-educated young people, more secondary schools were established, and the state claimed the sole right to set standards and to supervise the newly established schools.

Four different types of secondary schools developed:

By the turn of the 20th century, the four types of schools had achieved equal rank and privilege, although they did not have equal prestige.[14]

After 1919, the Weimar Republic established a free, universal four-year elementary school (Grundschule). Most pupils continued at these schools for another four-year course. Those who were able to pay a small fee went on to a Mittelschule that provided a more challenging curriculum for an additional one or two years. Upon passing a rigorous entrance exam after year four, pupils could also enter one of the four types of secondary school.

During the Nazi era (1933–1945), though the curriculum was reshaped to teach the beliefs of the regime,[15] the basic structure of the education system remained unchanged.

The German Democratic Republic (East Germany) started its own standardized education system in the 1960s. The East German equivalent of both primary and secondary schools was the Polytechnic Secondary School (Polytechnische Oberschule), which all students attended for 10 years, from the ages of 6 to 16. At the end of the 10th year, an exit examination was set. Depending upon the results, a pupil could choose to come out of education or undertake an apprenticeship for an additional two years, followed by an Abitur. Those who performed very well and displayed loyalty to the ruling party could change to the Erweiterte Oberschule (extended high school), where they could take their Abitur examinations after 12 school years. Although this system was abolished in the early 1990s after reunification, it continues to influence school life in the eastern German states.[citation needed]

After World War II, the Allied powers (Soviet Union, France, United Kingdom, and the U.S.) ensured that Nazi ideology was eliminated from the curriculum. They installed educational systems in their respective occupation zones that reflected their own ideas. When West Germany gained partial independence in 1949, its new constitution (Grundgesetz) granted educational autonomy to the state (Länder) governments. This led to widely varying school systems, often making it difficult for children to continue schooling whilst moving between states.[16]

Multi-state agreements ensure that basic requirements are universally met by all state school systems. Thus, all children are required to attend one type of school (five or six days a week) from the age of 6 to the age of 16. A pupil may change schools in the case of exceptionally good (or exceptionally poor) ability. Graduation certificates from one state are recognized by all the other states. Qualified teachers are able to apply for posts in any of the states.

Since the 1990s, a few changes have been taking place in many schools:

In 2000 after much public debate about Germany's perceived low international ranking in Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), there has been a trend towards a less ideological discussion on how to develop schools. These are some of the new trends:

In Germany, education is the responsibility of the states (Länder) and part of their constitutional sovereignty (Kulturhoheit der Länder). Teachers are employed by the Ministry of Education for the state and usually have a job for life after a certain period (verbeamtet) (which, however, is not comparable in timeframe nor competitiveness to the typical tenure track, e.g. at universities in the US). This practice depends on the state and is currently changing. A parents' council is elected to voice the parents' views to the school's administration. Each class elects one or two Klassensprecher (class presidents; if two are elected usually one is male and the other female), who meet several times a year as the Schülerrat (students' council).

A team of school presidents is also elected by the pupils each year, whose main purpose is organizing school parties, sports tournaments and the like for their fellow students. The local town is responsible for the school building and employs the janitorial and secretarial staff. For an average school of 600 – 800 students, there may be two janitors and one secretary. School administration is the responsibility of the teachers, who receive a reduction in their teaching hours if they participate.

Church and state are separated in Germany. Compulsory school prayers and compulsory attendance at religious services at state schools are against the constitution. (It is expected, though, to stand politely for the school prayer even if one does not pray along.)

Over 99% of Germans aged 15 and above are estimated to be able to read and write.[17]

German preschool is known as a Kindergarten (plural Kindergärten) or Kita, short for Kindertagesstätte (meaning "children's daycare center"). Children between the ages of 2 and 6 attend Kindergärten, which are not part of the school system. They are often run by city or town administrations, churches, or registered societies, many of which follow a certain educational approach as represented, e.g., by Montessori or Reggio Emilia or Berliner Bildungsprogramm. Forest kindergartens are well established. Attending a Kindergarten is neither mandatory nor free of charge, but can be partly or wholly funded, depending on the local authority and the income of the parents. All caretakers in Kita or Kindergarten must have a three-year qualified education, or be under special supervision during training.

Kindergärten can be open from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. or longer and may also house a Kinderkrippe, meaning crèche, for children between the ages of eight weeks and three years, and possibly an afternoon Hort (often associated with a primary school) for school-age children aged 6 to 10 who spend the time after their lessons there. Alongside nurseries, there are day-care nurses (called Tagesmutter, plural Tagesmütter—the formal, gender-neutral form is Tagespflegeperson(en)) working independently from any pre-school institution in individual homes and looking after only three to five children typically up to three years of age. These nurses are supported and supervised by local authorities.

The term Vorschule, meaning 'pre-school', is used both for educational efforts in Kindergärten and for a mandatory class that is usually connected to a primary school. Both systems are handled differently in each German state. The Schulkindergarten is a type of Vorschule.

During the German Empire, children were able to pass directly into secondary education after attending a privately run, fee-based Vorschule which then was another sort of primary school. The Weimar Constitution banned these, feeling them to be an unjustified privilege, and the Basic Law still contains the constitutional rule (Art. 7 Sect. VI) that: Pre-schools shall remain abolished.

Homeschooling is – between Schulpflicht (compulsory schooling) beginning with elementary school to 18 years – illegal in Germany. The illegality has to do with the prioritization of children's rights over the rights of parents: children have the right to the company of other children and adults who are not their parents, also parents cannot

Www Pure Voyeur Com

American Sex Videolar

Https Www Xvideos Com Video10552873

Male To Female Anime

Public Flashing Xxx

Constitutional Right to an Education: Germany - loc.gov

What We Teach When We Teach German Constitutional Law: An ...

German private schools ′violating constitution′ | Germany ...

Education in Germany - Wikipedia

Primary and secondary education in Germany

The German School System | The German Way & More

Germany - Constitution

Teaching in Germany | Teach Away

Germany's Constitution of 1949 with Amendments through 2014

Education | The German Way & More

How German Schools Teach Constitution

/159628442-56a8fcaf3df78cf772a2885c.jpg)