Hiroya Sakurai. Shoot, edit and watch

Gendai Eye (Viktor Belozerov)

Gendai Eye <Viktor Belozerov>, August 27, 2021

Correction of English translation: Henry Dutton Foster Jr. <Associate Professor, Seian University of Art and Design>

The guest of today's interview is a completely unfamiliar character for the Russian audience. However, in Japan, Hiroya Sakurai is a famous video artist, a representative of the second generation of Japanese video art. The 1980s became a golden age of discovering oneself through new technologies that were more affordable and flexible than those of the generation of the late 1960s. Limited access to editing equipment, the appearance of the first sites for the demonstration of works, the distribution of cassettes, stories about colleagues and teachers, Bill Viola and other foreign artists of that time - this is our plan for this rather long dialogue.

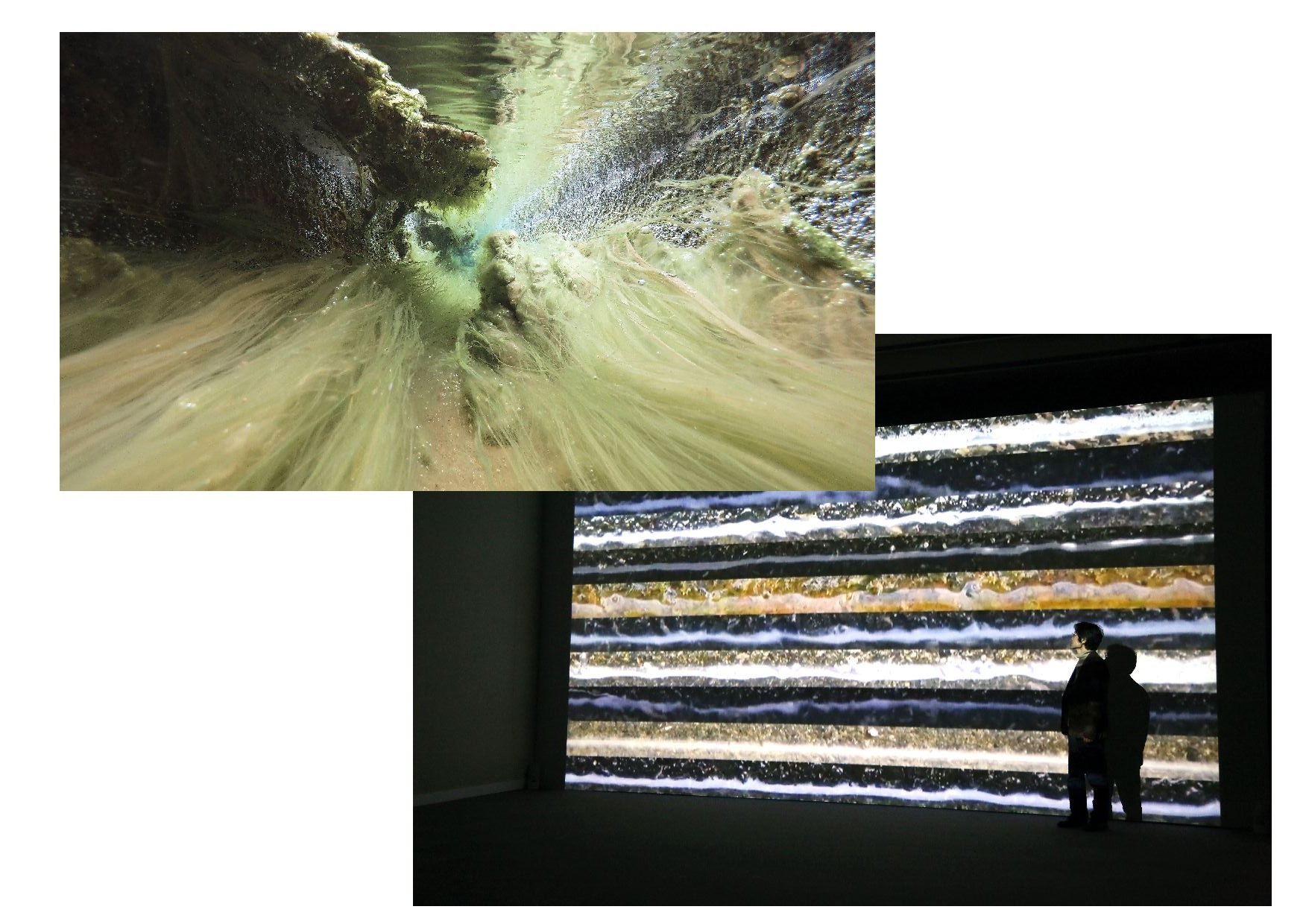

Part of the interview is dedicated to Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, the mentor of our interview’s protagonist, who can rightfully be considered a pioneer in the development of Japanese video art. And, of course, we did not ignore the work of Sakurai himself, whose piece, «The Stream X» (2019) can be viewed at the festival NOW&AFTER’20’21. The 10th festival will be held from 7 to 26 September 2021 at the Center for Contemporary Art Winzavod (Moscow).

This conversation could be endless, because there is no information about Japanese video art in Russian. This interview represents a significant addition to the conversation about the history of video art in Japan, which has already been started in one previous article. My sincere thanks to Hiroya Sakurai for our conversation and for providing valuable images from his archive.

Preface from Hiroya Sakurai:

For this interview, I would like to thank all the people who have supported me in my creative activities, especially Katsuhiro Yamaguchi and Suzushi Hanayagi, both of whom have now passed away. I would also like to thank Fujiko Nakaya for her support at Video Gallery SCAN. Finally, I would like to thank Viktor Belozerov for his appreciation of contemporary Japanese art and for planning this interview.

Interview with Hiroya Sakurai

Gendai Eye: If we go back to the beginning of your career, to the 1980s, what was your idea of Japanese and foreign video art? What were you watching at the time? By that time, Video Gallery SCAN and Image Forum already existed, as did the creators from the first generation of Japanese video art. How much did these things help you to understand the nature of video art?

Hiroya Sakurai: I started making artworks in 1981 when I was a student at Musashino Art University. The reason I was able to do this was because the university had an expensive Sony U-matic tape editing machine for professional use. The shooting equipment was purchased jointly by a video production group formed by students; we purchased a Sony beta tape camera and a video cassette recorder. One of the artists in the group who is still active today is the musician Towa Tei. This equipment made it possible for me to create my works. In this way, I believe that the majority of video artists at the time were professors and students who belonged to universities that had access to production equipment, which was much more expensive than it is today.

I produced work at the university from 1981 to 1983, and submitted it to the Video Gallery SCAN contest. Many artists who were submitting to the Video Gallery SCANs were using the equipment at their universities. I met students there from Tama Art University (Professor Sakumi Hagiwara), Kyushu Institute of Design (Professor Toshio Matsumoto), and Nihon University (Professor Fujiko Nakaya) [1]. They were around 21 years old at the time. I was 23 years old in 1981. Also among them were Tsunekazu Ishihara (director and game designer, president of Pokemon) and Hironori Terai (producer of MTV JAPAN).

The first generation of Japanese video art had a great influence on me. In particular, I was influenced by Fujiko Nakaya, Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, Nobuhiro Kawanaka, Toshio Matsumoto, and Shuji Terayama. Fujiko Nakaya was the owner of Video Gallery SCAN. At the regular screenings held there, a collection of works distributed by EAI (Electronic Arts Intermix) was screened to introduce information on video art from overseas [2], including Bill Viola, Gary Hill, Tony Oursler, and others. Other regular programs included documentaries on the New York art scene and live performances by Paul Tschinkel on the New York music scene.

The artists and audience at Video Gallery SCAN were interested in video’s unique potential to express things that cannot be expressed on film. All the works were played on the gallery's Umatic video player and viewed on the large monitor TVs in the gallery. Image Forum, on the other hand, used film projectors to show the works and projected them on the screen. However, the artists viewed the works shown at both Video Gallery SCAN and Image Forum equally. The book "Videomaking: A New Tool for Communication" (1979) by Nobuhiro Kawanaka, the leader of Image Forum, had a great influence on my methodology of video expression. I believe that many video artists have expanded their range of expression by viewing the programs of both Image Forum and Video Gallery SCAN. [3]

Yamaguchi Katsuhiro was a professor of mine when I was a master's student at Tsukuba University. When I was a student, I assisted him in his solo video installation exhibition "Future Garden" (1984). In addition to being directly influenced by him, I had a great deal of communication with the students under his supervision. These included Toshio Iwai, Radical TV (Daizaburo Harada and Haruhiko Shono), Nobumichi Tosa (Meiwa Denki), and photographer Naoya Hatakeyama. [4]

At the time, Toshio Matsumoto was presenting his video works at the Video Gallery SCAN and was also a judge for the competition there. I watched them. But among his works, one that had a particularly big impact on me was "Mona Lisa" (1973), which I saw in the 70's, when his work was aired on TV. It was one of the works that introduced me to visual expressions other than dramatic films in my teens.

I was greatly influenced by Video Gallery SCAN, where Bill Viola and Gary Hill were jurors for the competition and there was a question and answer session between the audience and the artists. Bill Viola in particular was working on "Hatsuyume" in Japan at the time, so we attended the screening where he gave his presentation. Lastly, Shuji Terayama is not often mentioned in the history of video art [5]. However, his film works in the late 1970s ("The Eraser / Keshigomu", 1977, "Issunboshiwo kijutsu suru kokoromi", 1977) are video chroma-key works. His works were screened at Image Forum as film works, and they had a great influence on me as a video artist at that time, as they were an excellent expression of the unique video method.

GE: Among Japanese authors, was there any division between experimental cinema and video art?

HS: In the 80's, video art was looking for possibilities unique to the video medium, so there was the distinction that video artists were not trying to reproduce film art. There was no conflict between film and video. It was a time when many filmmakers were also experimenting with video. There was a trend to place monitors in lighted museums and art galleries rather than in darkened movie theaters to show finished films. Single screen styles were the mainstream, but there were also video performances held in galleries, involving monitors and the body. Others involved real-time closed-circuit installations with no recording.

GE: Was your interest in the sound component somehow related to the collectives of sound artists, such as Yasunao Tone or others?

HS: No, not at all. At the time, I discovered the similarities between music and film in a lecture by Bill Viola, who was experimenting with using music composition methods in filmmaking. I was experimenting with using music composition methods in visual expression, and Kuniharu Akiyama's How to Listen to Contemporary Music was my favorite book. In this book, he introduces Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer's musique concrète and Luigi Russolo's noise music. I was considering how to use the techniques of video representation and the techniques of their music, and I remember that in the SCAN open call exhibition, about 50% of the works used background music, and about 50% used the sound of simultaneous recording in the field to great effect.

GE: How big is the influence of foreign artists and their introduction of technology and new capabilities into the Japanese world of video art? First of all, I mean Michael Goldberg ("Satellite Video Exchange") and then Bill Viola, who helped to found video gallery SCAN with Fujiko Nakaya?

HS: Michael Goldberg was a member of the jury for SCAN's open call exhibition and I met him at the presentation. I learned a lot from his judgement. He selected my film “Scramble” (1983). But I think he had a bigger impact on Nakaya's generation, including Nobuhiro Kawanaka, than my generation. There is a section in Nobuhiro Kawanaka's book "Videomaking" where he mentions how Michael Goldberg contributed to Japanese video art by lecturing on the mechanics and operation of the shooting equipment used in making video works. As for Bill Viola, I have written elsewhere about many of his influences. There were so many opportunities for screenings, and I saw “Reflecting Pool” many times back then. I remember appreciating his voice in the impressive “Space Between Teeth” and “The Wheel of Becoming” as excellent examples of the new video medium. I also went to see the premiere of “Hatsuyume” and the Japanese premiere of “I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like” (1986).

GE: What role did the artists who returned from abroad (Mako Idemitsu, Takahiko Iimura, Shigeko Kubota) play? [6]

HS: Mako Idemitsu was a well-known artist in the video art exhibitions of the time, and we students in our twenties were influenced by her works. The Great Mother series, in which a monitor appears in the video, impressed me. Jung's psychology was involved in the concept of the work. When it comes to video art, the focus tends to be on the technique. However, I learned from Idemitsu's work that the concept is the key to expression. Takahiko Imura's closed-circuit, real-time installations taught me that video art is a real-time visual medium which is different from film. Like him, I was greatly influenced by Katsuhiro Yamaguchi's "Las Meninas" and Norio Imai's closed-circuit installations. Especially from Norio Imai, I learned the possibility of video performance using closed circuits. [7]

I was influenced by Shigeko Kubota as well as the works of Nam June Paik. I was interested in her performance activities in Fluxus. I was also influenced by the installation of Duchamp's work at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, and the construction of the monitor display. Incidentally, a large-scale retrospective of Shigeko Kubota's work is currently being held in Japan. At that time, Idemitsu, Iimura, and Imai were often shown in many video art exhibitions. At the time, Ko Nakajima also presented many of his works for us. [8]

Komai Gallery in Tokyo (1984, not all participants).

GE: Please tell us about Video Cocktail I-II-III (1984-86). Did you participate in all three versions of this project? How did this group go from exhibiting at Komai Gallery to the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art exhibition?

HS: I participated in all of them. The first one was at Komai Gallery in Tokyo. The second exhibition was at NEWS Gallery in Tokyo. Tsuneo Nakai and Yasuo Shinohara had been working as established artists in the field of experimental film. Shinohara was a video artist and an engineer at Sony. They took the lead in organizing the first three events. The third exhibition, which was larger in scale, was organized as a special exhibition at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art at the urging of Nakai. As a result, Sony became a sponsor and provided us with many 27-inch monitors. Thanks to this, Tsuneo Nakai presented a video installation consisting of about 10 TV monitors, which was a large-scale project at that time. I was also able to present my video installation "TV Terrorist".

I was a graduate student at the University of Tsukuba. I had been showing my new works once a year at the SCAN open call exhibition. I was not particularly interested in having a group exhibition, but rather continued to work toward the goal of having my work selected for SCAN three times, because if I had three works selected for SCAN, I could have a solo exhibition at SCAN. I achieved my goal of having a solo exhibition at SCAN in 1985.

In 1984, Nam June Paik had a video installation exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum with a large-scale monitor TV provided by Sony. The Kobe Port Island Exposition (1981) and the World Design Exposition (1989) also featured video exhibitions using large-scale monitor TVs.

GE: Video Cocktail, as I understand it, had the opportunity to distribute its cassettes. What was the process of selling and distributing cassettes at that time?

HS: I think that's an important question. But I don't remember. The only thing I remember is that we decided to put a watermark on the video to protect the copyright. I think it was very innovative for us to sell our own collection of works independently instead of through the gallery system.

GE: I would like to talk about your works of that time. As far as I understand, some of the most high-profile projects of that period were the projects: “TV Terrorist” and “Kids Who Never Heard of Bill Viola”. What were these works about?

HS: “TV Terrorist" is a video installation that I presented at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in 1986. It has no political meaning, but is a satirical expression of the negative impact of the media on society. The large monitor showing my image is covered with a cloth and only my eyes are visible like a face mask. The incomplete shape of the human body, with only the head and no arms or legs, is an inner mental image of people formed by misunderstandings and false information from TV broadcasts. After graduating from Tsukuba University, I was unable to use editing equipment. As a result, I decided to create the installation as a way to express myself without the need for editing. The video that plays in the installation is a 10-minute loop of close-ups of both eyes without editing.

"Kids Who Never Heard of Bill Viola" is a screening program that I curated for "Video Cocktail III" in 1986. The program consisted of artists from the younger generation who were not directly influenced by Bill Viola. The currently active musician Towa Tei participated in this program. I am glad he became a great artist.

Art in Tokyo (1986). (2) Video performance "Ghost in the TV" by Hiroya Sakurai and Naruaki

Sasaki at "Video Cocktail III" in Hara Museum of Contemporary Art (1986). (3) Film

"Obsession I" by Hiroya Sakurai at "Video Cocktail I" in Tokyo (1984)

GE: How did you meet Katsuhiro Yamaguchi and how did you become his assistant? Was this related to the emergence of his project Art-Unis, aimed at the younger generation of video artists, and the founding of a studio on Awaji Island?

HS: Two years after I graduated from the graduate school of Tsukuba University, Yamaguchi asked me to come to his office in Tokyo, Studio LOCUS. The reason was that he was asked to be the video operator for "Mrs. Hands and Feet" (1987) with Katsuhiro Yamaguchi and Suzushi Hayanaga. Immediately after signing the contract, I accompanied him to performances in France, Spain and Italy.

Art-Unis was founded in 1982 before I joined his studio. I assisted Yamaguchi in the production of a video installation of his work for Art-Unis' 1987 "International High Technology & Art 1987" in Tokyo. These art and technology exhibitions moved on to the establishment of the 1st International Biennale in Nagoya - ARTEC in 1989 of which Yamaguchi was one of the committee members. From 1990 onward, the idea of an art village on Awaji Island also emerged. The Awaji Island Art Village was officially launched in 1992 with the "1st World Environmental Art Symposium". I was involved in planning the events for this conference. I was also involved in the planning of events for the conference and planning of the construction of Katsuhiro Yamaguchi's Art Factory on Awaji Island in 1994.

However, my main jobs were the editing of his video installations and films from 1987 to 1999. In particular, I remember "From Darkness 2000 to Light" (2000). I shot landscapes with a video camera and edited as an operator. This work was presented at the Nizayama Forest Art Museum, Toyama and won the Mainichi Art Award in 2000.

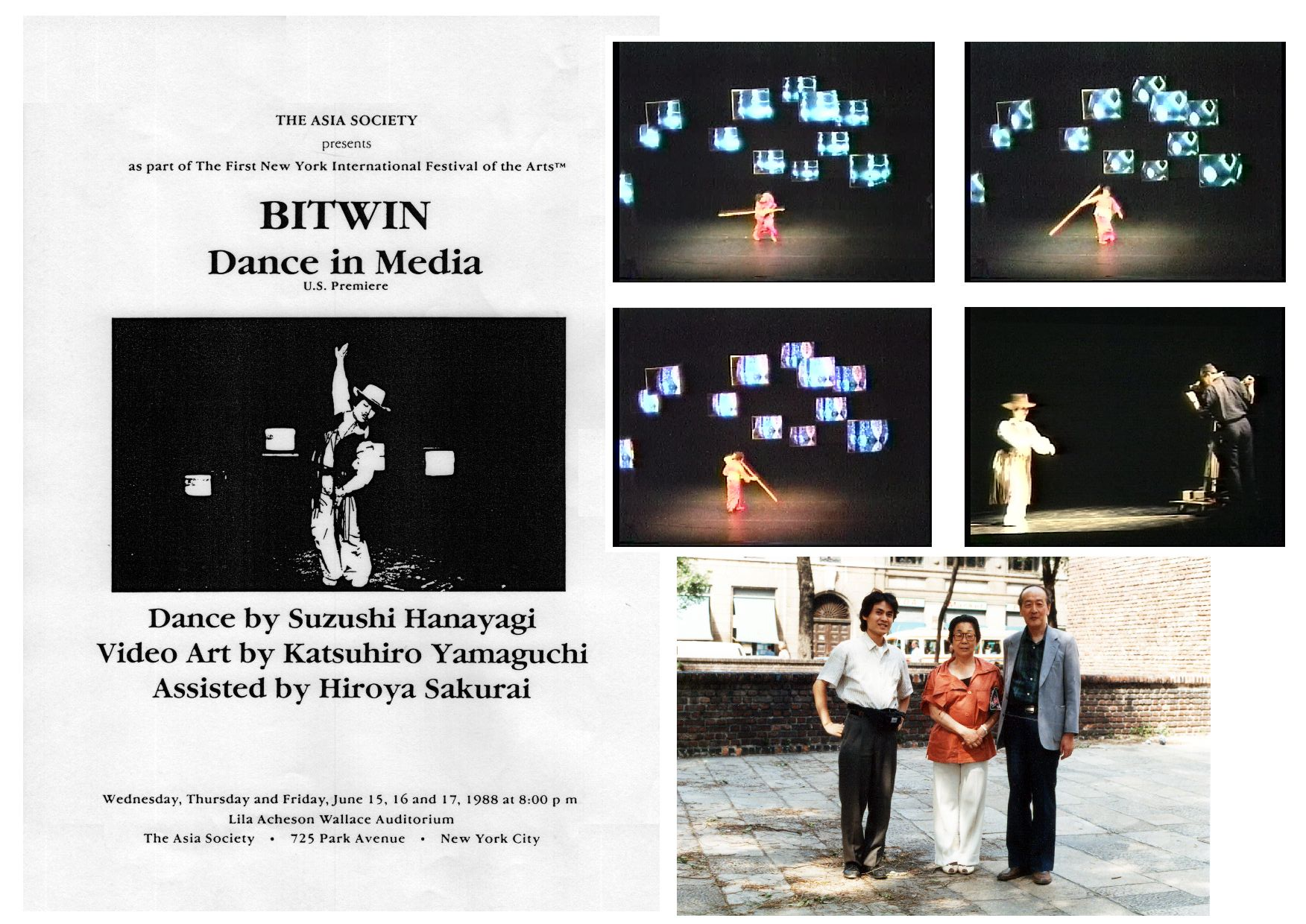

Katsuhiro Yamaguchi (video art) and Hiroya Sakurai (assistant) in New York (1988). (2)

Video performance "Bitwin, Dance in Media" in New York (1988). (3) A group photo at video

performance "Mrs. Hands and Feet". Right: Katusuhiro Yamaguchi; Center: Suzushi

Hanayagi; Left: Hiroya Sakurai.

GE: Do you know something about the collaboration between Katsuhiro Yamaguchi and choreographer Hayanaga Suzushi, including their "Mrs. Hands and Feet”? It is very interesting, because in one of the interviews with Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, I discovered that this project was shown in Moscow in 1992.

HS: I accompanied the first overseas performance of "Mrs. Hands and Feet" (1987), a collaboration between Katsuhiro Yamaguchi and choreographer Suzushi Hanayagi, as a video operator in Bobigny, France. A kaleidoscope effect was created by attaching square mirror tubes to the front of the monitor. Twelve square tubes were transported from Japan. Yamaguchi's video camera shows Hanayagi's image on the monitor in real time, which is reflected in the mirror and moves in a kaleidoscopic pattern. When it was over, the monitor would switch to an abstract electronic image that had been recorded. I was the operator of the switcher that switched between these live and recorded electronic images. The show toured from Bobigny, France, to Madrid and Milan. I remember that the performances were very successful and well received. During a rehearsal in one of the cities, I remember being surprised when a hanging monitor broke down. I also remember that John Cage visited us when we performed in New York in 1988. I have a good memory of meeting him after the performance. I was not the operator in Moscow. A student from Tsukuba University, where Yamaguchi was teaching, went to Moscow. I don't know how the performance went there, but I heard it was a success. There is a video recording of a rehearsal in New York from that time.

GE: You worked with Yamaguchi for over 15 years. What can you tell us about his experience? How did it change your attitude towards video? Have you ever collaborated with him on his “Imaginarium”? [9]

HS: It is difficult to explain in a few words. If you have read his books, you will know that he was an artist who thought and acted very logically, with no ambiguity. His work instructions were clear. In his office, there was a large painting by the German artist Jan Voss that covered the entire wall. For me, it was like a visualization of his thought process.

I worked on the concept of "Imaginarium" as a staff member. Yamaguchi's debut work is Vitrine. Vitrine is a box-shaped work with corrugated glass on top of a painting. As the visitor moves in front of the work, which has a lens-like glass surface, it changes the pattern of the painting. The viewer can see the work in different ways depending on their position. This work involves the environment in which the viewer stands.

In 1994, I set up the video installation "Katsuhiro Yamaguchi Reflection 1958-1994" as a staff member under Yamaguchi. At this time, a live camera was used to film the surface of the Vitrine, and the images were shown live on a multi-monitor screen that was viewed through the lens of a column placed next to the camera. It was a work based on the concept of Imaginarium, which was reconstructed by quoting information taken from the original.

GE: You also mentioned that you had a collaboration with Toru Takemitsu. When was it and what did you work on together?

HS: In 1998, Yamaguchi produced a video work titled "30 years: Hisao Domoto 1988 16'30", which traced the evolution of the paintings created by the painter Hisao Domoto over a period of 30 years. I remember that it was not a documentary based on interviews, but an experimental film approach using colors and shapes, with music by Toru Takemitsu as background music and textures of the paintings shot in close-up. I worked with Takemitsu at an editing studio in Tokyo when he dubbed the music for the film. I don't think the music was newly written, but had been previously composed by Takemitsu. I don't think this work has been sold on the market. Takemitsu was Yamaguchi’s best friend. They were members of “Experimental Workshop”. [10]

Hiroya Sakurai at Aqua Passage, Shiga Citizens' Theatre for the Arts in Japan (2012).

GE: Your series of projects “Stream” has been going on for several years now. How do you manage to continue working with the same environmental element, but at the same time represent and study it from different angles?

HS: From 2011 to 2018, The Stream was limited to water flow in paddy field canals and scenes within the canals. The scene in the channel was constantly changing depending on the annual climate (sunshine hours, rainfall, and so on), so I was able to follow the various dynamics of the water flow. In addition, waterways are only designed to carry water for humans. However, when plants and animals that use the waterways as their living environment come together, the waterways show up in a diversity of life-related forms. Each year I have been able to discover new subjects from that diverse information.

After 2019, I expanded the concept of streams to include "streams" other than water. These include the flow of air, logistics, and vehicles outside the waterways. In fact, the flow of water in rice paddies does not flow naturally, but as part of the workings of society.

Hiroya Sakurai was born in Yokohama, Japan in 1958. Professor, Seian University of Art and Design. Sakurai’s work can be found in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada and J.Paul Getty Trust. Sakurai was awarded at “35th Asolo Art Film Festival (2016)", Italy, "39th Tokyo Video Festival", "18th FILE 2017 ", São Paulo (2017) and "56th Ann Arbor Film Festival" (2018). Exhibitions include "4th Sydney Biennale (1982),"Postwar Art in Japan", The Getty Center, Los Angeles(2007),"62nd Melbourne International Film Festival"(2013),"58th San Francisco International Film Festival" (2015) ,"21st Japan Media Arts Festival", Tokyo (2018) and "24th Rhode Island International Film Festival"(2020)

Sakurai expresses the transformation of nature controlled by mankind on film from the perspective of formative art. His main subject matter is water flowing through rice paddy canals, which is the subject of his series "The Stream".

Website — Facebook — Film-Makers Cooperative

Notes:

[1] Sakumi Hagiwara (1946), Toshio Matsumoto (1932-2017), Fujiko Nakaya (1933) are representatives of the first generation of Japanese video art, who started working in this direction in the mid-1960s.

[2] EAI (Electronic Arts Intermix) is an organization dedicated to the preservation and distribution of video and media art. Fujiko Nakaya, thanks to her overseas trips and the connections established during them, managed to agree on the display of various works of foreign artists in her gallery.

[3] Video Gallery Scan and Image Forum were two central venues for displaying video works by artists in Japan at the time. The first was organized by Fujiko Nakaya , appearing in the very early 1980s. The second site began as a center for experimental cinema, and by the 1970s expanded its range of acceptance by various authors. It still exists today.

[4] Radical TV (Daizaburo Harada and Haruhiko Shono) is a once successful duo of two video artists who turned their attention to creating video clips and other formats of entertainment content. Later, Haruhiko Shono (1960) became a famous game designer, he has a fairly impressive list of game projects, implemented by him in the 1990s and the first half of the 2000s. Toshio Iwai (1962) likewise combined the opportunity to realize artistic projects and games. His Bikkuri Mouse for Playstation 2 is popular. Nobumichi Tosa (1967) is the creator of hundreds of meaningless devices, successfully realizing himself not only in art and design, but also in popular culture. Naoya Hatakeyama (1958) is one of the most famous photographers of the early 2000s. His landscapes, studies of the urban environment, markedly distinguished him against the background of other authors of that time.

[5] Shuji Terayama (1935-1983) is in fact better known for his theatrical and feature-length film work than for his video work. However, his contributions are comparable to those of his close colleagues like Toshio Matsumoto.

[6] Mako Idemitsu (1940), Takahiko Iimura (1937), Shigeko Kubota (1937-2015), like many artists of that time, left Japan, but most often not with the aim of leaving the country forever, but to gain experience and expand their ideas about various forms of art. Their return to Japan, partial or complete, had a significant impact not only on the ability to share knowledge with the younger generation, but also on the initiative to organize spaces for the display of video works.

[7] Norio Imai (1946) began as part of the Gutai group, making minimalist canvases with convex shapes that seemed to emerge from the canvas space. Later, he began to integrate video recordings into his already sculptural forms.

[8] Ko Nakajima (1941) was also one of the central video artists of his time, a member of the Video Earth group. He managed to combine discoveries in the field of video art and animation. His most iconic work is Mt. Fuji (1984).

[9] "Imaginarium" is an art representation concept created by Katsuhiro Yamaguchi in the 1970s. It is based on the rejection of the definition of art, replacing it with an "imaginary performance" that passes through the technological environment, becoming information for people who need it. The person becomes not a recipient, but an appraiser. One of the first works that was implemented to demonstrate the concept of "Imaginarium" was "Las Meninas" (1974-75), in which the camera followed the gaze of the viewer, transforming the pictorial nature into an information environment. In another aspect related to the form and functioning of museums, Katsuhiro Yamaguchi was interested in the theoretical developments of Frederick Kiesler. He was interested in the opportunity to combine the space of the viewer and the work in one contextual field. Imaginarium was envisioned as a large project, an information network capable of going beyond the institutional space.

[10] The Experimental Workshop (Jikken Kōbō) was one of the first collectives in post-war Japan to take an interest in exploring the possibilities of interdisciplinary art practices. The group was formed in 1951 by the critic and artist Takiguchi Shuzo. Katsuhiro Yamaguchi was one of the main authors of the group, which included not only artists, writers, musicians, but also engineers. Their practice was based on an interest in the stage space, the use of advanced technologies (projectors), as well as experimental cinematography. The group was disbanded in 1957.