Hedy Lamarr: The Hollywood Star Who Invented “Frequency Hopping” (The Basis of Wi-Fi and Bluetooth)

@Science in telegram

In the history of science and technology, there are many examples of significant discoveries made by people whose primary careers were far removed from invention. One of the most striking examples is Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000) — an Austrian-American actress from the Golden Age of Hollywood who developed a technology foundational to modern wireless communications.

The Inventor’s Biography

Hedy Lamarr (born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler) was born on November 9, 1914, in Vienna, Austria, into a wealthy, socially prominent Jewish family. Her father, a bank director, and her mother, a concert pianist, gave her an upper-class education typical of the time: ballet, piano, and horseback riding lessons.

From a young age, Hedy showed an extraordinary curiosity and an engineering mind. At age five, she dismantled and reassembled a music box to understand how it worked. While walking around Vienna with her father, he would explain how trams worked and how electricity was generated at power plants—laying the foundation for her interest in engineering.

Despite her technical inclination, a career in science or engineering was not an option for girls in 1930s Vienna. At 16, Hedy began acting, and by 18, she starred in the Czech film Ecstasy (1933), which caused international scandal for its nude scenes and was banned in countries including Nazi Germany.

In 1933, Hedy married Austrian arms manufacturer Fritz Mandl. The marriage was unhappy; her jealous and controlling husband forced her to attend business meetings with clients—including those from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Though she was forbidden from speaking, she listened carefully to technical discussions about torpedo guidance systems and other military technologies, which would later prove invaluable to her invention work.

In 1937, Hedy fled her husband and Austria, already aligned with Hitler’s antisemitic regime. In London, she met MGM Studios head Louis B. Mayer, who offered her a Hollywood contract. Upon arriving in the U.S., she changed her name to Hedy Lamarr and soon became one of the most sought-after actresses of her time, starring in films such as Algiers (1938) and Samson and Delilah.

From Film Star to Inventor

Despite her successful film career, Lamarr never abandoned her interest in invention. She built a “inventor’s corner” in her home with a drafting table and walls lined with engineering books. After 12–15 hour shooting days at MGM, she often skipped Hollywood parties to work on her ideas.

Among her inventions were: an improved traffic signal, a dissolvable tablet to carbonate water, a glow-in-the-dark dog collar, and a swiveling shower seat for safe transfers from the bathtub. But her most important invention was a system of frequency hopping, developed in collaboration with avant-garde composer George Antheil.

Frequency Hopping Technology

In 1940, as Nazi Germany ramped up its military power and U-boats devastated Atlantic shipping, Lamarr wanted to help the U.S. war effort. Drawing on knowledge gained during her marriage, she understood that enemy forces could easily detect and jam radio-controlled torpedoes by targeting the signal’s frequency.

During a musical jam session with George Antheil, the two realized that if musicians could “hop” in sync across piano keys while playing a tune, and the listener didn’t know the melody, it would be impossible to predict the next note. This insight led to their invention.

Their system proposed using two synchronized devices—one on the ship and one in the torpedo—that would hop between radio frequencies following a preset pattern. The communication signal would remain uninterrupted despite constantly changing frequencies. To enemy jammers, the signal would sound like random noise, impossible to block effectively.

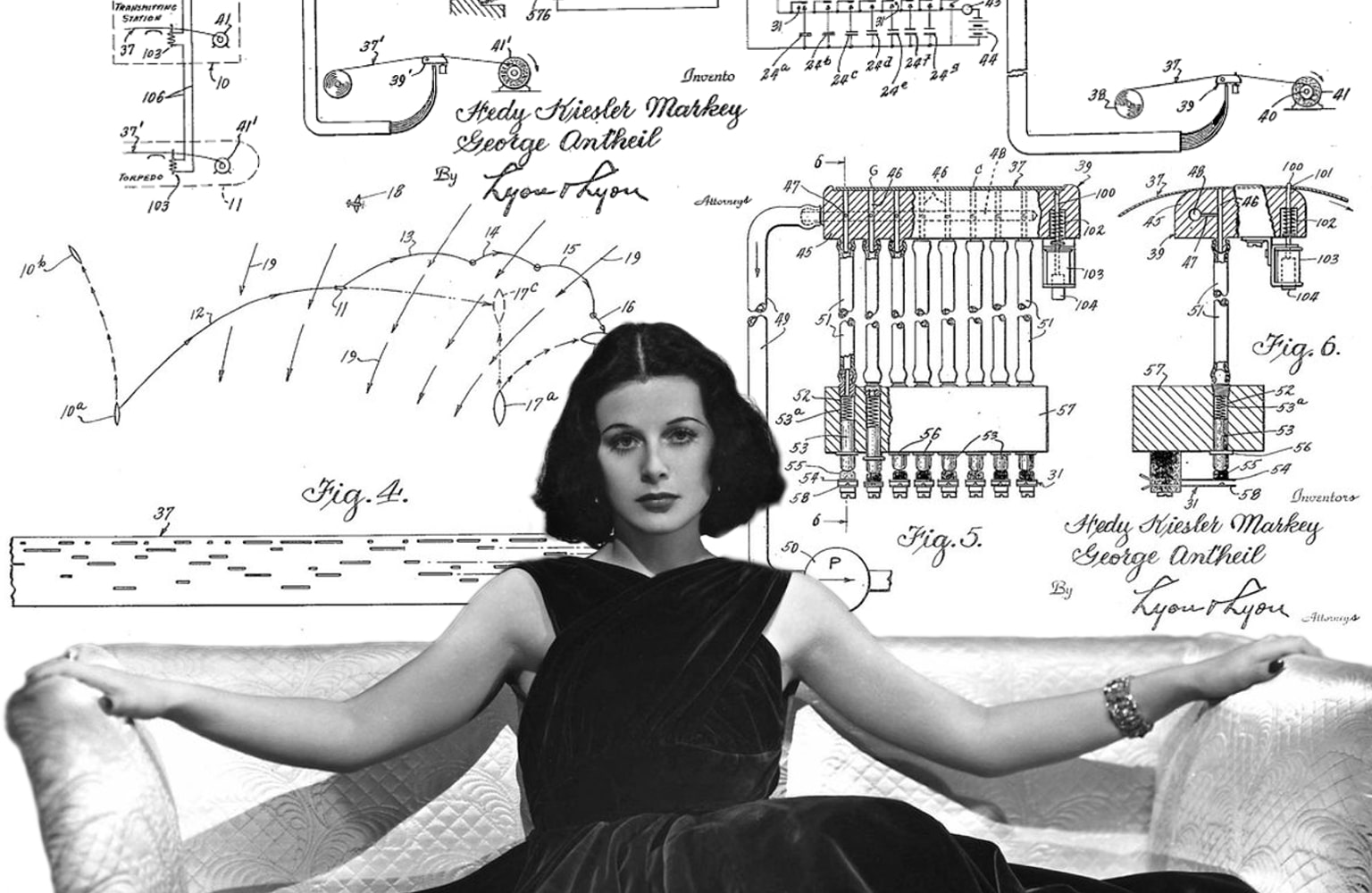

Technically, the system used a perforated paper tape—similar to that used in player pianos (Antheil’s specialty)—to synchronize jumps across 88 frequencies (the number of piano keys). This made the radio signal nearly impossible to detect or jam.

Patent and Rejection by the Navy

In 1942, Lamarr and Antheil received U.S. Patent No. 2,292,387 for their “Secret Communication System,” describing the use of frequency hopping to secure radio-controlled torpedoes. Supported by the National Inventors Council, they connected with a physicist from Caltech to help develop the electronics.

However, when the invention was presented to the U.S. Navy, it was rejected. As historian Richard Rhodes recounted, the military’s response was dismissive: “What, you want to put a player piano in a torpedo? Get out of here!” Instead of recognizing her as an inventor, Lamarr was asked to use her beauty to sell war bonds.

The patent was classified and shelved until the end of the war. Lamarr and Antheil returned to their main professions, assuming their invention would never be realized.

Second Life of the Technology and Modern Applications

Despite the initial rejection, the frequency hopping concept was not forgotten. In the 1950s, Sylvania Corporation used it for secure submarine communications. By the early 1960s, the U.S. Navy adopted it to prevent Soviet jamming during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Antheil died in 1959. Lamarr lived on, unaware that their invention was being put into use. By the 1970s, frequency hopping was used in the first generation of cellular phones, enabling hundreds of users to share limited radio spectrum. The technology was also adapted into early mobile networks.

By the 1990s, frequency hopping had become so common that the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted it as a standard for secure radio communications. Today, this principle is fundamental to Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and GPS—all essential in modern life.

Late Recognition

For decades, Lamarr’s contribution remained unknown to the public. Only in the 1990s, when she was in her 80s, did a group of engineers realize that “Hedwig Kiesler Markey,” listed on the patent, was actually the Hollywood star Hedy Lamarr.

In 1997, at age 84, she received the Pioneer Award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Upon hearing the news, she reportedly said: “It’s about time.” In 2014, she was posthumously inducted into the U.S. National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Scientific and Cultural Legacy

Lamarr’s story demonstrates how gender stereotypes and bias can obstruct recognition of scientific achievements. Her beauty, which made her a Hollywood icon, also caused many to dismiss her as a serious inventor. As Lamarr once remarked: “Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

Today, she is recognized not only as a film legend but also as a pioneering inventor whose work laid the foundation for the wireless communication revolution. Her story inspires new generations—especially women pursuing careers in science and technology.

The frequency hopping method developed by Lamarr and Antheil is a classic example of how interdisciplinary thinking and innovation can lead to breakthroughs. Combining military engineering concepts with musical composition, they created a technology that eventually became crucial for global communication.

At Google, Lamarr holds iconic status. In 2015, the company celebrated her 101st birthday with a special Google Doodle. According to designer Jennifer Hom: “In the Google geek community, Hedy Lamarr is a favorite… When a story involves a 1940s Hollywood actress who helped invent the technology we use in smartphones today, we have to share it with the world.”

The story of Hedy Lamarr is one of talent, curiosity, and ingenuity overcoming professional barriers and gender bias. Her contributions to wireless communication—made “between takes” on Hollywood film sets—show that scientific breakthroughs can come from the most unexpected places and people.

Today, every time we connect to Wi-Fi, use Bluetooth to share files, or navigate via GPS, we are, in a way, paying tribute to the inventive genius of Hedy Lamarr—the Hollywood star who changed the future of communication.