Had Her Holes

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

To revisit this article, select My Account, then

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories

Photograph by Edith Maybin, “Untitled” (2008) / Edwynn Houk Gallery

Sally packed devilled eggs—something she usually hated to take on a picnic, because they were so messy. Ham sandwiches, crab salad, lemon tarts—also a packing problem. Kool-Aid for the boys, a half bottle of Mumm’s for herself and Alex. She would have just a sip, because she was still nursing. She had bought plastic champagne glasses for the occasion, but when Alex spotted her handling them he got the real ones—a wedding present—out of the china cabinet. She protested, but he insisted, and took charge of them himself, the wrapping and packing.

“Dad is really a sort of bourgeois gentilhomme,” Kent would say to Sally a few years later, when he was in his teens and acing everything at school, so sure of becoming some sort of scientist that he could get away with spouting French around the house.

“Don’t make fun of your father,” Sally said mechanically.

“I’m not. It’s just that most geologists seem so grubby.”

The picnic was in honor of Alex’s publishing his first solo paper, in Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie. They were going to Osler Bluff because it figured largely in his research, and because Sally and the children had never been there.

They drove a couple of miles down a rough country road—having turned off the highway and then off a decent unpaved country road—and found a place for cars to park, with no cars in it at present. A sign was painted on a board and needed retouching: “CAUTION. DEEP-HOLES.”**

Why the hyphen? Sally thought. But who cares?

The entrance to the woods looked quite ordinary and unthreatening. Sally understood, of course, that these woods were on top of a high bluff, and she expected a daunting lookout somewhere. She did not expect the danger that had to be skirted almost immediately in front of them.

Deep chambers, really, some the size of a coffin, some much bigger than that, like rooms cut out of the rocks. Corridors zigzagging between them, and ferns and mosses growing out of the walls. Not enough greenery, however, to make any sort of cushion over the rubble below. The path went meandering between them, over hard earth and shelves of not quite level rock.

“Oooeee,” came the cry of the boys, Kent and Peter, nine and six years old, running ahead.

“No tearing around in here,” Alex called. “No stupid showing off, you hear me? You understand? Answer me.”

They said O.K., and he proceeded, carrying the picnic basket and apparently believing that no further fatherly warning was necessary. Sally stumbled after him faster than was easy for her, with the diaper bag and the baby, Savanna. She couldn’t slow down till she had her sons in sight, saw them trotting along taking sidelong looks into the black crevasses, still making exaggerated but discreet noises of horror. She was nearly crying with exhaustion and alarm and some familiar sort of seeping rage.

The lookout did not appear until they had followed the dirt-and-rock path for what seemed to her like half a mile, and was probably a quarter mile. Then there was a brightening, an intrusion of sky, and her husband halted ahead. He gave a cry of arrival and display, and the boys hooted with true astonishment. Sally, emerging from the woods, found them lined up on an outcrop above the treetops—above several levels of treetops, as it turned out—with the summer fields spread far below in a shimmer of green and yellow.

As soon as she put Savanna down on her blanket, she began to cry.

Alex said, “I thought she got her lunch in the car.”

She got Savanna latched on to one side and with her free hand unfastened the picnic basket. This was not how Alex had envisioned things. But he gave a good-humored sigh and retrieved the champagne glasses from their wrappings in his pockets, placing them on their sides on a patch of grass.

“Glug glug. I’m thirsty, too,” Kent said, and Peter immediately imitated him.

Alex said to Sally, “What did you bring for them to drink?”

“Kool-Aid, in the blue jug. The plastic glasses are in a napkin on top.”

Of course, Alex believed that Kent had started that nonsense not because he was really thirsty but because he was crudely excited by the sight of Sally’s breast. He thought it was high time that Savanna was transferred to the bottle—she was nearly six months old. And he thought Sally was far too casual about the whole procedure, sometimes going around the kitchen doing things with one hand while the infant guzzled. With Kent sneaking peeks and Peter referring to Mommy’s milk jugs. That came from Kent, Alex said. Kent was a troublemaker and the possessor of a dirty mind.

“Well, I have to do things,” Sally said.

“That’s not one of the things you have to do. You could have her on the bottle tomorrow.”

“I will soon. Not quite tomorrow, but soon.”

But here she is, still letting Savanna and the milk jugs dominate the picnic.

The Kool-Aid is poured, then the champagne. Sally and Alex touch glasses, with Savanna between them. Sally has her sip and wishes she could have more. She smiles at Alex to communicate this wish, and maybe the idea that it would be nice to be alone with him. He drinks his champagne, and, as if her sip and smile were enough to soothe him, he starts in on the picnic. She points out which sandwiches have the mustard he likes and which have the mustard she and Peter like and which are for Kent, who likes no mustard at all.

While this is going on, Kent manages to slip behind her and finish up her champagne. Peter must have seen him do this, but for some peculiar reason he does not tell on him. Sally discovers what has happened some time later and Alex never knows about it at all, because he soon forgets that there was anything left in her glass and packs it neatly away with his own, while telling the boys about dolostone. They listen, presumably, as they gobble up the sandwiches and ignore the devilled eggs and crab salad and grab the tarts.

Dolostone, Alex says, is the thick caprock they can see. Underneath it is shale, clay turned into rock, very fine, fine-grained. Water works through the dolostone and when it gets to the shale it just lies there; it can’t get through the thin layers. So the erosion—that’s the destruction of the dolostone—is caused as the water works its way back to its source, eats a channel back, and the caprock develops vertical joints. Do they know what “vertical” means?

“Up and down,” Kent says lackadaisically.

“Weak vertical joints, and they get to lean out and then they leave crevasses behind them and after millions of years they break off altogether and go tumbling down the slope.”

Sally clamps her mouth down on the automatic injunction to be careful. Alex looks at her and approves of the clamping down. They smile faintly at each other.

Savanna has fallen asleep, her lips slack around the nipple. With the boys out of the way, it’s easier to detach her. Sally can burp her and settle her on the blanket, without worrying about an exposed breast. If Alex finds the sight distasteful—she knows he dislikes the whole conjunction of sex and nourishment, his wife’s breasts turned into udders—he can look away, and he does.

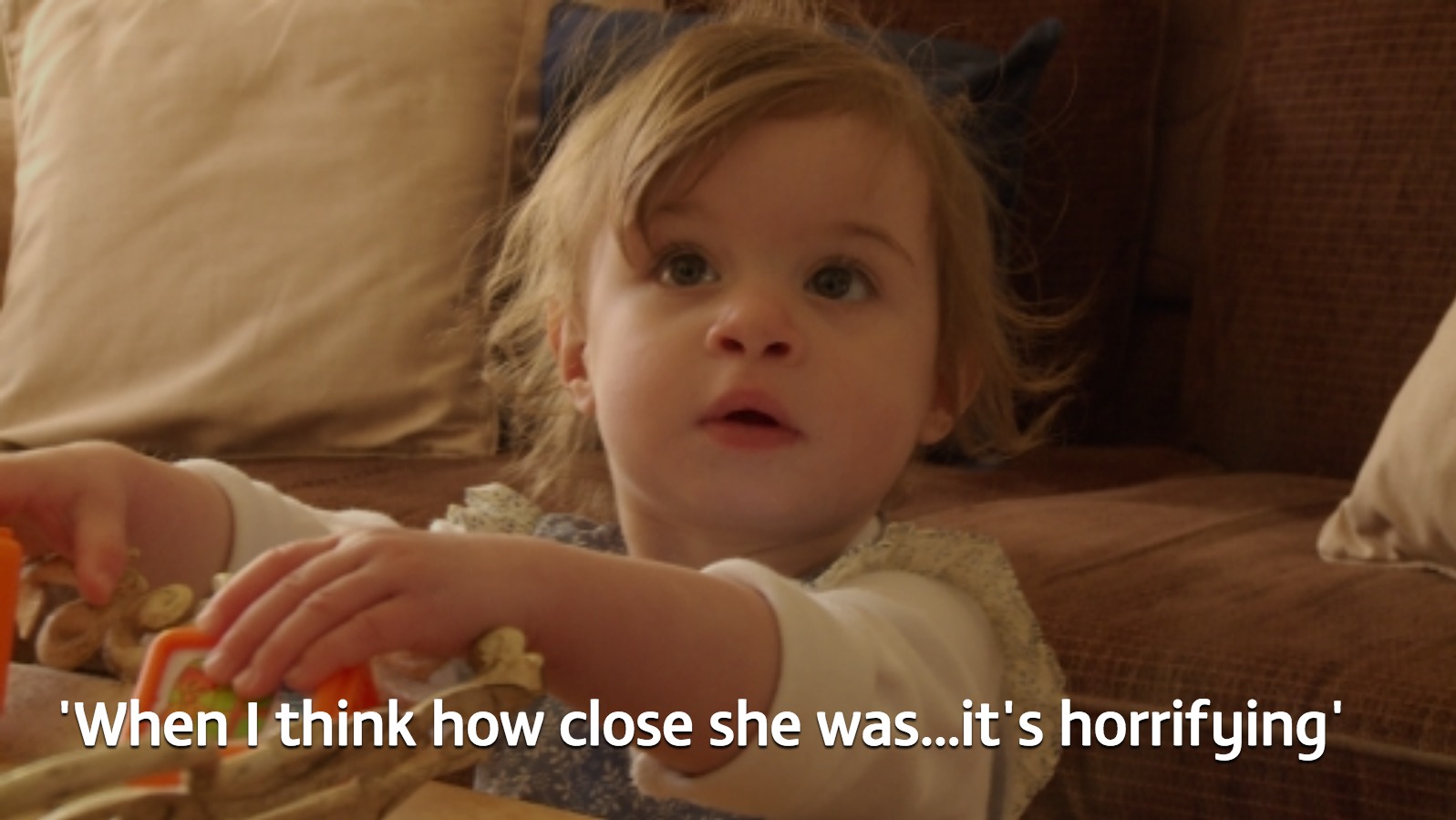

As she buttons herself up, there comes a cry, not sharp but lost, diminishing, and Alex is on his feet before she is, running along the path. Then a louder cry getting closer. It’s Peter.

Sally will always believe that she knew at once—even before she heard Peter’s voice, she knew what had happened. If an accident had happened, it would not be to her six-year-old, who was brave but not inventive, not a showoff. It would be to Kent. She could see exactly how—peeing into a hole, balancing on the rim, teasing Peter, teasing himself.

He was alive. He was lying far down in the rubble at the bottom of the crevasse, but he was moving his arms, struggling to push himself up. Struggling so feebly. One leg caught under him, the other oddly bent.

“Can you carry the baby?” she said to Peter. “Go back to the picnic and put her on the blanket and watch her. That’s my good boy. My good strong boy.”

Alex was on his way into the hole, scrambling down, telling Kent to stay still. Getting down in one piece was just possible. It would be getting Kent out that was hard.

Should she run to the car and see if there was a rope? Tie the rope around a tree trunk? Maybe tie it around Kent’s body so she could lift him when Alex raised him up to her?

There wouldn’t be a rope. Why would there be a rope?

Alex had reached him. He bent and lifted him. Kent gave a beseeching scream of pain. Alex draped him around his shoulders, Kent’s head hanging down on one side and useless legs—one so unnaturally protruding—on the other. He rose, stumbled a couple of steps, and while still hanging on to Kent dropped back down to his knees. He had decided to crawl and was making his way—Sally understood this now—to the rubble that partly filled the far end of the crevasse. He shouted some order to her without raising his head, and though she could not make out any word she knew what he wanted. She got up off her knees—why was she on her knees?—and pushed through some saplings to that edge of the rim, where the rubble came to within perhaps three feet of the surface. Alex was still crawling along with Kent dangling from him like a shot deer.

Kent would have to be raised up by his father, pulled to the solid shelf of rock by his mother. He was a skinny boy, who had not yet reached his first spurt of growth, but he seemed as heavy as a bag of cement. Sally’s arms could not do it on the first try. She shifted her position, crouching instead of lying flat on her stomach, and with the full power of her shoulders and chest and with Alex supporting and lifting Kent’s body from beneath they heaved him over. Sally fell back with him in her arms and saw his eyes open, then roll back in his head as he fainted again.

When Alex had clawed his way out, they collected the other children and drove to the Collingwood Hospital. There seemed to be no internal injury. Both legs were broken. One break was clean, as the doctor put it. The other leg was shattered.

“Kids have to be watched every minute in there,” he said sternly to Sally, who had gone into the examining room with Kent while Alex managed Peter and Savanna. “Haven’t they got any warning signs up?”

With Alex, she thought, he would have spoken differently. “That’s the way boys are. Turn your back and they’re tearing around where they shouldn’t be,” he would have said.

Her gratitude—to God, whom she did not believe in, and to Alex, whom she did—was so immense that she resented nothing.

It was necessary for Kent to spend the next six months out of school, strung up for the first few weeks in a rented hospital bed. Sally picked up and turned in his school assignments, which he completed in no time. Then he was encouraged to go ahead with Extra Projects. One of these was “Travels and Explorations—Choose Your Country.”

“I want to pick somewhere nobody else would pick,” he said.

The accident and the convalescence seemed to have changed him. He acted older than his age now, less antic, more serene. And Sally told him something that she had not told to another soul. She told him how she was attracted to remote islands. Not to the Hawaiian Islands or the Canaries or the Hebrides or the Isles of Greece, where everybody wanted to go, but to small or obscure islands that nobody talked about and that were seldom, if ever, visited. Ascension, Tristan da Cunha, Chatham Island and Christmas Island and Desolation Island and the Faeroes. She and Kent began to collect every scrap of information they could find about these places, not allowing themselves to make anything up. And never telling Alex what they were doing.

“He would think we were off our heads,” Sally said.

Desolation Island’s main boast was of a vegetable, of great antiquity, a unique cabbage. They imagined worship ceremonies for it, costumes, and cabbage parades in its honor.

Sally told her son that, before he was born, she had seen footage on television of the inhabitants of Tristan da Cunha disembarking at Heathrow Airport, having all been evacuated, owing to a great volcanic eruption on their island. How strange they had looked, docile and dignified, like creatures from another century. They must have adjusted to England, more or less, but when the volcano quieted down, a couple of years later, they almost all wanted to go home.

When Kent went back to school, things changed, of course, but he still seemed mature for his age, patient with Savanna, who had grown venturesome and stubborn, and with Peter, who always burst into the house as if on a gale of calamity. And he was especially courteous to his father, bringing him the paper that he had rescued from Savanna and carefully refolded, pulling out his chair at dinnertime.

“Honor to the man who saved my life,” he might say, or “Home is the hero.”

He said this rather dramatically, though not at all sarcastically, yet it got on Alex’s nerves. Kent got on his nerves, had done so even before the deep-hole drama.

“Cut that out,” Alex said, and complained privately to Sally.

“He’s saying you must have loved him, because you rescued him.”

“Christ, I’d have rescued anybody.”

“Don’t say that in front of him. Please.”

When Kent got to high school, things with his father improved. He chose to focus on science. He picked the hard sciences, not the soft earth sciences, and even this roused no opposition in Alex. The harder the better.

But after six months at college Kent disappeared. People who knew him a little—there did not seem to be anyone who claimed to be a friend—said that he had talked of going to the West Coast. A letter came, just as his parents were deciding to go to the police. He was working at a Canadian Tire in a suburb just north of Toronto. Alex went to see him there, to order him back to college. But Kent refused, said that he was very happy with his job, and was making good money, or soon would be, when he got promoted. Then Sally went to see him, without telling Alex, and found him jolly and ten pounds heavier. He said it was the beer. He had friends now.

“It’s a phase,” she said to Alex when she confessed the visit. “He wants to get a taste of independence.”

“He can get a bellyful of it, as far as I’m concerned.”

Kent had not said where he was living, and when she made her next visit to Canadian Tire she was told that he had quit. She was embarrassed—she thought she caught a smirk on the face of the employee who told her—and she did not ask where Kent had gone. She assumed he would get in touch, anyway, as soon as he had settled again.

He did write, three years later. His letter was mailed in Needles, California, but he told them not to bother trying to trace him there—he was only passing through. Like Blanche, he said, and Alex said, “Who the hell is Blanche?”

“Just a joke,” Sally said. “It doesn’t matter.”

Kent did not say where he had been or whether he was working or had formed any connections. He did not apologize for leaving his parents without any information for so long, or ask how they were, or how his brother and sister were. Instead, he wrote pages about his own life. Not the practical side of his life but what he believed he should be doing—what he was doing—with it.

“It seems so ridiculous to me,” he said, “that a person should be expected to lock themselves into a suit of clothes. I mean, like the suit of clothes of an engineer or doctor or geologist, and then the skin grows over it, over the clothes, I mean, and that person can’t ever get them off. When we are given a chance to explore the whole world of inner and outer reality and to live in a way that takes in the spiritual and the physical and the whole range of the beautiful and the terrible available to mankind, that is pain as well as joy and turmoil. This way of expressing myself may seem over-blown to you, but one thing I have learned to give up is intellectual pridefulness—”

“He’s on drugs,” Alex said. “You can tell a mile off. His brain’s rotted with drugs.”

In the middle of the night he said, “Sex.”

Sally was lying beside him, wide awake.

“It’s what makes you do what he’s talking about—become a something-or-other so that you can earn a living. So that you can pay for your steady sex and the consequences. That’s not a consideration for him.”

“Getting down to basics is never very romantic. He’s not normal is all I’m trying to say.”

Further on in the letter—or the rampage, as Alex called it—Kent said that he had been luckier than most people, in having had what he called his “near-death experience,” which had given him perhaps an extra awareness, and he would be forever grateful to his father, who had lifted him back into the world, and to his mother, who had lovingly received him there.

He wrote, “Perhaps in those moments I was reborn.”

“Don’t,” Sally said. “You don’t mean it.”

“I don’t know whether I do or not.”

That letter, signed with love, was the last they heard from him.

Peter went into medicine, Savanna into law.

To her own surprise, Sally became interested in geology. One night, in a trusting mood after sex, she told Alex about the islands—though not about her fantasy that Kent was now living on one or another of them. She said that she had forgotten many of the details she used to know, and that she should look all these places up in the encyclopedia, where she had first got her information. Alex said that everything she wanted to know could probably be found on the Internet now. Surely not something so obscure, she said, and he got her out of bed and downstairs, and there in no time, before her eyes, was Tristan da Cunha, a green plate in the South Atlantic Ocean, with information galore. She was shocked and turned away, and Alex, who was disappointed in her, asked why.

“I don’t know. Maybe I don’t want it so real.”

He said that she needed something to do. He had just retired from teaching at the time and was planning to write a book. He needed an assistant and he could not call on graduate students now as he had been able to when he was still on the faculty. (She didn’t know if this was true or not.) She reminded him that she knew nothing about rocks, and he said never mind that, he could use her for scale, in the photographs.

So she became the small figure in black or bright clothing, contrasting with the ribbons of Silurian or Devonian rock or with the gneiss formed by intense compression, folded and deformed by clashes of the North American and the Pacific plates to make the present continent. Gradually she learned to use her eyes and apply her knowledge, till she could stand in an empty suburban street and realize that far beneath her shoes was a crater filled with rubble that had never been seen, because there had been no eyes to see it at its creation or thr

Milf Heels Fuck

Gagged Lesbian Slave

Panty Gagged Story Deviantart

Black Teen Handjob

Matures Handjob Pics

"She Had Holes in Her Memory" by Kathy Moore | ArtFields ...

Holes (novel) - Wikipedia

Deep-Holes | The New Yorker

Holes: The Warden Quotes | SparkNotes

Linda Walker | Holes Wiki | Fandom

Helen McCrory remembered: ‘She had a brightness about her ...

Questions and answers - Holes

Holes: Chapters 25–29 | SparkNotes

Had Her Holes