Government Canada At Least Private Ownership There

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Peter Munk Centre for Free Enterprise Education

Many people often look to Europe as an example of what Aristotle called the good lifethink of their pleasant cities and obvious regard for art and history. But heres something else Canadians can learn from Europe: how many governments there are much better at balancing the rights of private property owners with regulations that restrict property and lessen its value.

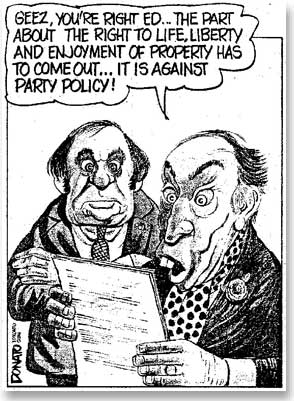

Some background: when a government (anywhere) uses regulation to partly or wholly freeze propertyby requiring a setback or declaring a plot of land ecologically sensitivesome label it a regulatory taking. Others call it a de facto expropriation. Literally, a government takes or controls your property through regulation (laws and bylaws) but technically, you still own it.

Of course, the effect of such regulation in extreme cases is little different from actual expropriation: you cant use your property or profit from it. Except that when governments actually expropriate private property, well-established common law principles, sympathetic legislation, and Canadas courts all combine to usually give property owners at least some compensation in exchange.

But its a far different scenario when regulation is in play. When a Canadian government or bureaucracy decides your property must serve some public purpose, and then uses a law or regulation to wholly or partly freeze your property, youre lucky to get a single dime in compensation.

For example, in Vancouver in 2000, the City told the Canadian Pacific Railway that a 22- kilometre long stretch of CPR land was henceforth to be a public thoroughfare for bikes and pedestrians. The city was clear that no compensation would ever be paid. Neither would the City expropriate it (which would have triggered compensation statutes). Six years later, the Supreme Court of Canada endorsed what was effectively a land grab without compensation.

Heres another example. In 2005, the Ontario government created a greenbelt around Greater Toronto, freezing 1.8 million acres of land from development, only permitting prior usage to continue. The provincial government made clear that no compensation would be offered for the severe restrictions on use, or the decline in value for individual parcels of private property.

In any country with tens of millions of people, some regulation is a reality. But Sweden, Finland, Germany, Holland and others treat private property owners much more fairly, providing compensation for the effect of regulation on property values.

European governments are keenly aware of the need to plan with the rights of property owners in mind. In Germany, rights of property ownership are guaranteed in the Basic Law (Germanys constitution), meaning that financial damages caused by lawful planning decisions will guarantee compensation for the property owner.

Germanys leading scholar on the subject, Gerd Schmidt-Eisenstaedt, writes that compensation is forthcoming in such cases because In German legal doctrine, it is irrelevant whether liability for damages is caused by an expropriation decision

or by a regulation that restricts property rights. In the end, they are always a form of property restriction

When new government regulations in Finland prevented owners of a forest from cutting down trees for their forestry business, the forests owners were fully compensated for the four per cent decline in the value of their property. Similarly, in the Netherlands, compensation is also owed to the property owner due to restricted use.

And heres a unique twist: in Sweden and Germany, if government regulations freeze your private property for too long, you can legally demand the government buy itthis as opposed to watching government just regulate your property into disuse. A governments go-slow approach to ending a regulatory freeze on private property triggers a right to expropriation, and to again quote Schmidt-Eisenstaedt on Germany, the municipality cannot avoid paying compensation.

Does the European approach to private property regulation work? Yes, as Israeli academic Rachelle Alterman writes in her 13-country survey (which includes Canada as an example to avoid), the German planning law provides clear answers to almost every conceivable situation where an injury to property values may arise. As Alterman notes, the balance struck is widely accepted.

Some level of regulation is inevitable and there is nothing wrong or undesirable in wanting pedestrian and bike paths, or in protecting fragile environments. The glaring problem is in how Canadian governments can freeze and devalue private property through regulationand rarely provide compensation to the property owner. We could learn a lot from Europe.

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.

Economic Freedom of the World: 2020 Annual Report James Gwartney, Robert A. Lawson, Joshua C. Hall, Ryan Murphy, Niclas Berggren, Fred McMahon, Therese Nilsson

The Fraser Institute is an independent, non-partisan research and educational organization based in Canada. We have offices in Calgary, Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver.

© 2021 Fraser Institute. All rights reserved.

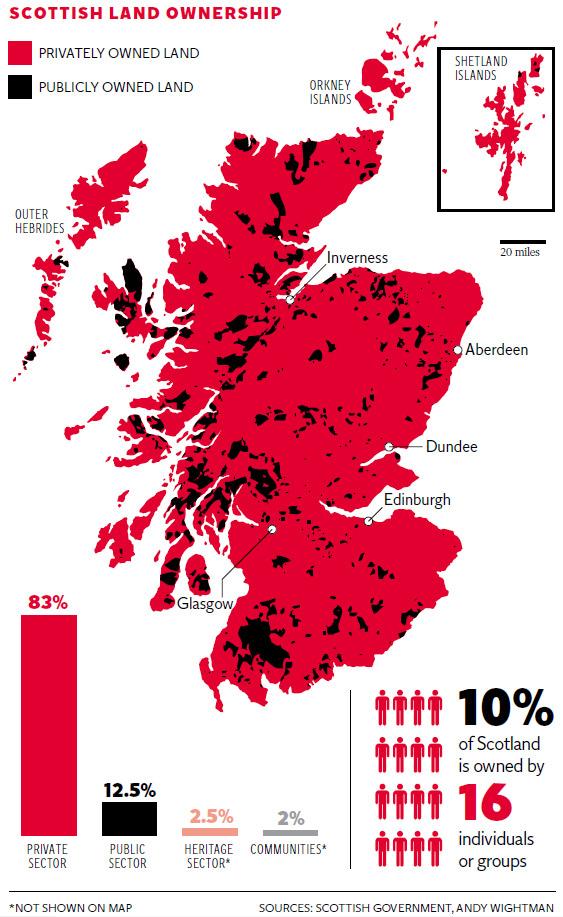

Land ownership in Canada is held by governments, Indigenous groups, corporations, and individuals. Canada is the second-largest country in the world by area; at 9,093,507 km² or 3,511,085 mi² of land (and more if fresh water is not included) it occupies more than 6% of the Earth's surface. Since Canada uses primarily English-derived common law, the holders of the land actually have land tenure (permission to hold land from the Crown) rather than absolute ownership.[1]

The majority of all lands in Canada are held by governments as public land and are known as Crown lands. About 89% of Canada's land area (8,886,356 km²) is Crown land, which may either be federal (41%) or provincial (48%); the remaining 11% is privately owned.[2] Most federally administered land is in the Canadian territories (Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Yukon), and is administered on behalf of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada; only 4% of land in the provinces is federally controlled, largely in the form of National Parks, Indian reserves, or Canadian Forces bases. In contrast, provinces hold much of their territory as provincial Crown land, which may be held as Provincial Parks or wilderness.

The largest class of landowners are the provincial governments, who hold all unclaimed land in their jurisdiction. Over 90% of the sprawling boreal forest of Canada is provincial Crown land.[3] Provincial lands account for 60% of the area of the province of Alberta,[4] 94% of the land in British Columbia,[5] 95% of Newfoundland and Labrador,[2] and 48% of New Brunswick.[6]

The largest single landowner in Canada by far, and by extension one of the world's largest, is the Government of Canada. The bulk of the federal government's lands are in the vast northern territories where Crown lands are vested in the federal, rather than territorial, government. In addition the federal government owns national parks, First Nations reserves and national defence installations.

Until the Natural Resources Acts of 1930 the prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, and to a limited extent British Columbia, did not control Crown lands or subsoil rights within their boundaries, which instead rested with the federal government. This deprived them of the benefits of royalties from mining, oil and gas, or forestry (stumpage) within their boundaries. This was a major source of Western alienation at the time.

In New France land was settled according to the seigneurial system, which was similar to the type of late feudalism practised in France at the time, and land was divided into long strip lots running back from the riverfront. This land pattern was also used in certain areas of Western Canada by French and Métis settlers.

In contrast, areas of British settlement used square block patterns of land distribution. Those in Eastern Canada contoured around geographical features and consisted of smaller lots. In Western Canada, where the American-influenced Dominion Land Survey was used, geographical features were largely ignored in favour of geometric standardization, with larger lots.

In Canadian law all lands are subject to the Crown, and this has been true since Britain acquired much of Eastern Canada from France by the Treaty of Paris (1763). However, the British and Canadian authorities recognized that indigenous peoples already on the lands had a prior claim, aboriginal title, which was not extinguished by the arrival of the Europeans. This is in direct contrast to the situation in Australia where the continent was declared terra nullius, or vacant land, and was seized from Aboriginal peoples without compensation. In consequence, all of Canada, save a section of southern Quebec exempted by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, is subject to Aboriginal title. Native groups historically negotiated treaties in which they traded tenure to the land for annuities and certain legal exemptions and privileges. Most of Western Canada was secured in this way by the government via the Numbered Treaties of 1871 to 1921, though not all groups signed treaties. In particular, in most of British Columbia Aboriginal title has never been transferred to the Crown. Many native groups, both those that have never signed treaties or those that are dissatisfied with the execution of treaties have made formal Aboriginal land claims against the government.

The Crown also gave tenure to much of Canada to a private company, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) which from 1670 to 1870 had a legal and economic monopoly on all land in the Rupert's Land territory (identical to the drainage basin of Hudson Bay), and later the Columbia District and the North-Western Territory (now British Columbia, the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut) were added to the HBC's lands, making it one of the largest private landowners in world history. In 1868 the Imperial Parliament passed the Rupert's Land Act that saw most of its land ownership transferred to the Dominion of Canada.

After Canada acquired the HBC's land in 1870, it used the land as an economic tool to promote settlement and development. Under the Dominion Lands Act system of 1871, huge areas were given to the Canadian Pacific Railway to fund its transcontinental line, other areas were reserved for school boards to be sold to fund education, and the rest was distributed to settlers for agriculture. Settlers paid a $10 fee and agreed to make some improvements within a specified time for 160 acres (65 ha), commonly known as a quarter section, of land. This was at a time of extreme land shortage in many agricultural areas of Europe, and aided in the rapid settlement of Western Canada. In areas where ranching was preferred to field agriculture (e.g. southern Alberta), large areas were leased to cattle barons at a nominal rate, allowing the development of an industrial-scale beef export industry centred on the city of Calgary.

At the same time, major land reforms were underway in Prince Edward Island to end the practice of absentee landlordism, which locals felt exploited them. The Government of Canada agreed to provide the Island with an $800,000 fund to purchase the remaining absentee landlord's estates as part of negotiations that brought PEI into Confederation.

Lands given out in the early years of the Dominion Lands Act included rights to the subsoil, including all minerals, oil, or natural gas found below the property.[citation needed] Later grants (after circa 1900) did not include subsoil rights. As a result, in the leading petroleum producing province of Alberta, 81% of the subsurface mineral rights are owned by the provincial Crown. The remaining 19% are owned by the federal Crown, individuals, or corporations.[7]

The result of cheaply distributed land and land reforms has been that modern Canada's land holding pattern is very egalitarian and large-scale[citation needed]. The majority of the population owns some land, often in large quantities. This is distinct from the few large landed estates and masses of tenant farmers typical of Old World and Latin American countries that have not enacted land reforms, the communal and state ownership typical of Communist countries, or the small-holdings in those parts of Europe and Latin America where the estates were broken up.

In the last century, the trend in Canada has been for a smaller percentage of people to own land, as more urbanization has turned people into renters. Still Canada has one of the world's highest rates of home ownership, which actually increased during the economic boom of the mid 2000s. In 2008, of the 12.4 million households in Canada, more than 8.5 million, over two-thirds (68.4%) owned their home, the highest rate since 1971. Much of the recent increases were in the form of condominiums, however, which are not land ownership in the traditional sense. In 1981, less than 4% of owner households owned condominiums. By 2001, this proportion had more than doubled to 9%, and by 2006, it had reached 10.9%.[8] Again, this reflects the impact of urbanization which has changed land holding patterns substantially.

In rural areas, the trend has been towards further farm consolidation. The number of farms has continually decreased since the end of the pioneering era in Western Canada (as recently as the 1930s in some regions, but more generally 1914), and at the same time, farm sizes have increased.

The other trend in rural Canada is for more urbanites to own summer homes, cottages, cabins, acreages, and hobby farms. This is especially apparent in areas that are situated within a convenient driving distance of major urban centres. Because Canada's major urban centres were historically founded on prime agricultural land, the end result is a permanent loss of agricultural land. This trend is further exacerbated by low-density residential subdivisions being constructed at the margins of cities, as well as the appearance of isolated rural residential "satellite subdivisions" specifically designed for complete car dependency.

^ http://www.aucc.ca/_pdf/english/programs/cepra/cad-wp3.pdf Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

^ a b V.P. NEIMANIS. "Crown Land". The Canadian Encyclopedia: Geography. Historica Foundation of Canada. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

^ State of Canada's Forests 2004–2005, p. 49

^ [1] Archived March 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

^ Minister of Agriculture and Lands; Crown Land Fact Sheet. Archived 2011-09-03 at the Wayback Machine

^ Mitchell, Simon J. (June 2003). "Who Owns Crown Lands?". Falls Brook Centre. Missing or empty |url= (help)

^ "Talk about Royalties, Facts on Royalties" (PDF). Alberta Government. September 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

^ "2006 Census: Changing patterns in Canadian homeownership and shelter costs". statcan.gc.ca. June 4, 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

Content is available under CC BY-SA 3.0 unless otherwise noted.

Xnxx Japan Cantik Menantu

Very Little Incest

Milftoon Fairly Oddparents Breaking Rules Porn

Swingers Club Seattle

Pictures Naked Women Hiking

Public Ownership | The Canadian Encyclopedia

Europe beats Canada on private property rights | Fraser ...

Land ownership in Canada - Wikipedia

GOVERNMENT-OWNED ENTERPRISES IN CANADA

Canada’s ownership and control rules: what every eager ...

Government and the Private Sector – Business Ethics

Mixed ownership companies in Canada - uvic.ca

Summary of privacy laws in Canada - Office of the Privacy ...

Foreign Ownership Restrictions and the… | Unique Properties

Privately held company - Wikipedia

Government Canada At Least Private Ownership There