German Soviet War

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

(Redirected from German-Soviet War)

"Great Patriotic War" redirects here. For a discussion of the term itself, see Great Patriotic War (term).

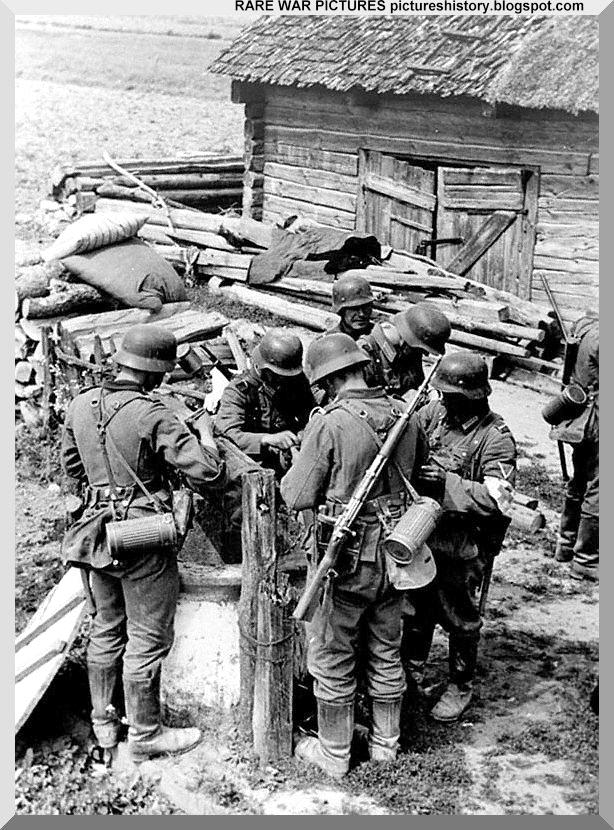

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of conflict between the European Axis powers against the Soviet Union (USSR), Poland and other Allies, which encompassed Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Northeast Europe (Baltics), and Southeast Europe (Balkans) from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945. It was known as the Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and some of its successor states, while everywhere else it was called the Eastern Front.

Clockwise from top left: Soviet T-34 tanks storming Berlin; German Tiger I tanks during the Battle of Kursk; German Stuka dive bombers on the Eastern Front, December 1943; Ivanhorod Einsatzgruppen photograph of German death squads murdering Jews in Ukraine; Wilhelm Keitel signing the German Instrument of Surrender; Soviet troops in the Battle of Stalingrad

22 June 1941 – 9 May 1945

(3 years, 10 months, 2 weeks and 2 days)

Europe east of Germany: Central and Eastern Europe, in later stages:Germany and Austria

Soviet victory as part of the Allied victory in the European theatre of World War II

Romania (from 1944)

Bulgaria (from 1944)

Finland (from 1944)

1941

3,767,000 troops

1942

3,720,000 troops

1943

3,933,000 troops

1944

3,370,000 troops

1945

1,960,000 troops

1941

(Front) 2,680,000 troops

1942

(Front) 5,313,000 troops

1943

(Front) 6,724,000 troops

1944

6,800,000 troops

1945

6,410,000 troops

5.1 million dead

4.5 million captured

See below.

8.7–10 million dead

4.1–5.7 million captured

See below.

Civilian casualties:

18–24 million civilians dead

See below.

The battles on the Eastern Front of the Second World War constituted the largest military confrontation in history.[2] They were characterised by unprecedented ferocity and brutality, wholesale destruction, mass deportations, and immense loss of life due to combat, starvation, exposure, disease, and massacres. Of the estimated 70–85 million deaths attributed to World War II, around 30 million occurred on the Eastern Front, including 9 million children.[3][4] The Eastern Front was decisive in determining the outcome in the European theatre of operations in World War II, eventually serving as the main reason for the defeat of Nazi Germany and the Axis nations.[5]

The two principal belligerent powers were Germany and the Soviet Union, along with their respective allies. Though never sending in ground troops to the Eastern Front, the United States and the United Kingdom both provided substantial material aid to the Soviet Union in the form of the Lend-Lease program along with naval and air support. The joint German–Finnish operations across the northernmost Finnish–Soviet border and in the Murmansk region are considered part of the Eastern Front. In addition, the Soviet–Finnish Continuation War is generally also considered the northern flank of the Eastern Front.

Germany and the Soviet Union remained unsatisfied with the outcome of World War I (1914–1918). Soviet Russia had lost substantial territory in Eastern Europe as a result of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918), where the Bolsheviks in Petrograd conceded to German demands and ceded control of Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Finland, and other areas, to the Central Powers. Subsequently, when Germany in its turn surrendered to the Allies (November 1918) and these territories became independent states under the terms of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 at Versailles, Soviet Russia was in the midst of a civil war and the Allies did not recognise the Bolshevik government, so no Soviet Russian representation attended.[6]

Adolf Hitler had declared his intention to invade the Soviet Union on 11 August 1939 to Carl Jacob Burckhardt, League of Nations Commissioner, by saying:

Everything I undertake is directed against the Russians. If the West is too stupid and blind to grasp this, then I shall be compelled to come to an agreement with the Russians, beat the West and then after their defeat turn against the Soviet Union with all my forces. I need the Ukraine so that they can't starve us out, as happened in the last war.[7]

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact signed in August 1939 was a non-aggression agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union. It contained a secret protocol aiming to return Central Europe to the pre–World War I status quo by dividing it between Germany and the Soviet Union. Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania would return to the Soviet control, while Poland and Romania would be divided.[citation needed] The Eastern Front was also made possible by the German–Soviet Border and Commercial Agreement in which the Soviet Union gave Germany the resources necessary to launch military operations in Eastern Europe.[8]

On 1 September 1939 Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. On 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Eastern Poland, and, as a result, Poland was partitioned among Germany, the Soviet Union and Lithuania. Soon after that, the Soviet Union demanded significant territorial concessions from Finland, and after Finland rejected Soviet demands, the Soviet Union attacked Finland on 30 November 1939 in what became known as the Winter War – a bitter conflict that resulted in a peace treaty on 13 March 1940, with Finland maintaining its independence but losing its eastern parts in Karelia.[9]

In June 1940 the Soviet Union occupied and illegally annexed the three Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania).[9] The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact ostensibly provided security to the Soviets in the occupation both of the Baltics and of the north and northeastern regions of Romania (Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia, June–July 1940), although Hitler, in announcing the invasion of the Soviet Union, cited the Soviet annexations of Baltic and Romanian territory as having violated Germany's understanding of the Pact. Moscow partitioned the annexed Romanian territory between the Ukrainian and Moldavian Soviet republics.

Adolf Hitler had argued in his autobiography Mein Kampf (1925) for the necessity of Lebensraum ("living space"): acquiring new territory for Germans in Eastern Europe, in particular Russia.[10] He envisaged settling Germans there, as according to Nazi ideology the Germanic people constituted the "master race", while exterminating or deporting most of the existing inhabitants to Siberia and using the remainder as slave labour.[11] Hitler as early as 1917 had referred to the Russians as inferior, believing that the Bolshevik Revolution had put the Jews in power over the mass of Slavs, who were, in Hitler's opinion, incapable of ruling themselves and had thus ended up being ruled by Jewish masters.[12]

The Nazi leadership, including Heinrich Himmler,[13] saw the war against the Soviet Union as a struggle between the ideologies of Nazism and Jewish Bolshevism, and ensuring territorial expansion for the Germanic Übermensch (superhumans), who according to Nazi ideology were the Aryan Herrenvolk ("master race"), at the expense of the Slavic Untermenschen (subhumans).[14] Wehrmacht officers told their troops to target people who were described as "Jewish Bolshevik subhumans", the "Mongol hordes", the "Asiatic flood" and the "red beast".[15] The vast majority of German soldiers viewed the war in Nazi terms, seeing the Soviet enemy as sub-human.[16]

Hitler referred to the war in radical terms, calling it a "war of annihilation" (Vernichtungskrieg) which was both an ideological and racial war. The Nazi vision for the future of Eastern Europe was codified most clearly in the Generalplan Ost. The populations of occupied Central Europe and the Soviet Union were to be partially deported to West Siberia, enslaved and eventually exterminated; the conquered territories were to be colonised by German or "Germanized" settlers.[17] In addition, the Nazis also sought to wipe out the large Jewish population of Central and Eastern Europe[18] as part of their program aiming to exterminate all European Jews.[19]

After Germany's initial success at the Battle of Kiev in 1941, Hitler saw the Soviet Union as militarily weak and ripe for immediate conquest. In a speech at the Berlin Sportpalast on 3 October, he announced, "We have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down."[20] Thus, Germany expected another short Blitzkrieg and made no serious preparations for prolonged warfare. However, following the decisive Soviet victory at the Battle of Stalingrad in 1943 and the resulting dire German military situation, Nazi propaganda began to portray the war as a German defence of Western civilisation against destruction by the vast "Bolshevik hordes" that were pouring into Europe.

Throughout the 1930s the Soviet Union underwent massive industrialisation and economic growth under the leadership of Joseph Stalin. Stalin's central tenet, "Socialism in One Country", manifested itself as a series of nationwide centralised Five-Year Plans from 1929 onwards. This represented an ideological shift in Soviet policy, away from its commitment to the international communist revolution, and eventually leading to the dissolution of the Comintern (Third International) organisation in 1943. The Soviet Union started a process of militarisation with the 1st Five-Year Plan that officially began in 1928, although it was only towards the end of the 2nd Five-Year Plan in the mid-1930s that military power became the primary focus of Soviet industrialisation.[21]

In February 1936 the Spanish general election brought many communist leaders into the Popular Front government in the Second Spanish Republic, but in a matter of months a right-wing military coup initiated the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939. This conflict soon took on the characteristics of a proxy war involving the Soviet Union and left wing volunteers from different countries on the side of the predominantly socialist and communist-led[22] Second Spanish Republic;[23] while Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Portugal's Estado Novo (Portugal) took the side of Spanish Nationalists, the military rebel group led by General Francisco Franco.[24] It served as a useful testing ground for both the Wehrmacht and the Red Army to experiment with equipment and tactics that they would later employ on a wider scale in the Second World War.

Germany, which was an anti-communist régime, formalised its ideological position on 25 November 1936 by signing the Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan.[25] Fascist Italy joined the Pact a year later.[23][26] Soviet Union negotiated treaties of mutual assistance with France and with Czechoslovakia with the aim of containing Germany's expansion.[27] The German Anschluss of Austria in 1938 and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia (1938–1939) demonstrated the impossibility of establishing a collective security system in Europe,[28] a policy advocated by the Soviet ministry of foreign affairs under Maxim Litvinov.[29][30] This, as well as the reluctance of the British and French governments to sign a full-scale anti-German political and military alliance with the USSR,[31] led to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Germany in late August 1939.[32] The separate Tripartite Pact between what became the three prime Axis Powers would not be signed until some four years after the Anti-Comintern Pact.

The war was fought between Nazi Germany, its allies and Finland, against the Soviet Union and its allies. The conflict began on 22 June 1941 with the Operation Barbarossa offensive, when Axis forces crossed the borders described in the German–Soviet Nonaggression Pact, thereby invading the Soviet Union. The war ended on 9 May 1945, when Germany's armed forces surrendered unconditionally following the Battle of Berlin (also known as the Berlin Offensive), a strategic operation executed by the Red Army.

The states that provided forces and other resources for the German war effort included the Axis Powers – primarily Romania, Hungary, Italy, pro-Nazi Slovakia, and Croatia. Anti-Soviet Finland, which had fought the Winter War against the Soviet Union, also joined the offensive. The Wehrmacht forces were also assisted by anti-Communist partisans in places like Western Ukraine, and the Baltic states. Among the most prominent volunteer army formations was the Spanish Blue Division, sent by Spanish dictator Francisco Franco to keep his ties to the Axis intact.[33]

The Soviet Union offered support to the partisans in many Wehrmacht-occupied countries in Central Europe, notably those in Slovakia, Poland. In addition, the Polish Armed Forces in the East, particularly the First and Second Polish armies, were armed and trained, and would eventually fight alongside the Red Army. The Free French forces also contributed to the Red Army by the formation of the GC3 (Groupe de Chasse 3 or 3rd Fighter Group) unit to fulfil the commitment of Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, who thought that it was important for French servicemen to serve on all fronts.

3,050,000 Germans, 67,000 (northern Norway); 500,000 Finns, 150,000 Romanians

Total: 3,767,000 in the east (80% of the German Army)

2,680,000 active in Western Military Districts out of 5,500,000 (overall); 12,000,000 mobilizable reserves

2,600,000 Germans, 90,000 (northern Norway); 600,000 Romanians, Hungarians, and Italians

Total: 3,720,000 in the east (80% of the German Army)

5,313,000 (front); 383,000 (hospital)

Total: 9,350,000

3,403,000 Germans, 80,000 (northern Norway); 400,000 Finns, 150,000 Romanians and Hungarians

Total: 3,933,000 in the east (63% of the German Army)

6,724,000 (front); 446,445 (hospital);

Total: 10,300,000

2,460,000 Germans, 60,000 (northern Norway); 300,000 Finns, 550,000 Romanians and Hungarians

Total: 3,370,000 in the east (62% of the German Army)

2,230,000 Germans, 100,000 Hungarians

Total: 2,330,000 in the east (60% of the German Army)

6,532,000 (360,000 Poles, Romanians, Bulgarians, and Czechs)

1,960,000 Germans

Total: 1,960,000 (66% of the German Army)

6,410,000 (450,000 Poles, Romanians, Bulgarians, and Czechs)

The above figures includes all personnel in the German Army, i.e. active-duty Heer, Waffen SS, Luftwaffe ground forces, personnel of the naval coastal artillery and security units.[37][38] In the spring of 1940, Germany had mobilised 5,500,000 men.[39] By the time of the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Wehrmacht consisted of c, 3,800,000 men of the Heer, 1,680,000 of the Luftwaffe, 404,000 of the Kriegsmarine, 150,000 of the Waffen-SS, and 1,200,000 of the Replacement Army (contained 450,400 active reservists, 550,000 new recruits and 204,000 in administrative services, vigiles and or in convalescence). The Wehrmacht had a total strength of 7,234,000 men by 1941. For Operation Barbarossa, Germany mobilised 3,300,000 troops of the Heer, 150,000 of the Waffen-SS[40] and approximately 250,000 personnel of the Luftwaffe were actively earmarked.[41]

By July 1943, the Wehrmacht numbered 6,815,000 troops. Of these, 3,900,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 180,000 in Finland, 315,000 in Norway, 110,000 in Denmark, 1,370,000 in western Europe, 330,000 in Italy, and 610,000 in the Balkans.[42] According to a presentation by Alfred Jodl, the Wehrmacht was up to 7,849,000 personnel in April 1944. 3,878,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 311,000 in Norway/Denmark, 1,873,000 in western Europe, 961,000 in Italy, and 826,000 in the Balkans.[43] About 15–20% of total German strength were foreign troops (from allied countries or conquered territories). The German high water mark was just before Battle of Kursk, in early July 1943: 3,403,000 German troops and 650,000 Finnish, Hungarian, Romanian and other countries troops.[35][36]

For nearly two years the border was quiet while Germany conquered Denmark, Norway, France, the Low Countries, and the Balkans. Hitler had always intended to renege on his pact with the Soviet Union, eventually making the decision to invade in the spring of 1941.

Some historians say Stalin was fearful of war with Germany, or just did not expect Germany to start a two-front war, and was reluctant to do anything to provoke Hitler. Others say that Stalin was eager for Germany to be at war with capitalist countries. Another viewpoint is that Stalin expected war in 1942 (the time when all his preparations would be complete) and stubbornly refused to believe its early arrival.[44]

British historians Alan S. Milward and M. Medlicott show that Nazi Germany—unlike Imperial Germany—was prepared for only a short-term war (Blitzkrieg).[45] According to Edward Ericson, although Germany's own resources were sufficient for the victories in the West in 1940, massive Soviet shipments obtained during a short period of Nazi–Soviet economic collaboration were critical for Germany to launch Operation Barbarossa.[46]

Germany had been assembling very large numbers of troops in eastern Poland and making repeated reconnaissance flights over the border; the Soviet Union responded by assembling its divisions on its western border, although the Soviet mobilisation was slower than Germany's due to the country's less dense road network. As in the Sino-Soviet conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway or Soviet–Japanese border conflicts, Soviet troops on the western border received a directive, signed by Marshal Semyon Timoshenko and General of the Army Georgy Zhukov, that ordered (as demanded by Stalin): "do not answer to any provocations" and "do not undertake any (offensive) actions without specific orders" – which meant that Soviet troops could open fire only on their soil and forbade counter-attack on German soil. The German invasion therefore caught the Soviet military and civilian leadership largely by surprise.

The extent of warnings received by Stalin about a German invasion is controversial, and the claim that there was a warning that "Germany will attack on 22 June without declaration of war" has been dismissed as a "popular myth". However, some sources quoted in the articles on Soviet spies Richard Sorge and Willi Lehmann, say they had sent warnings of an attack on 20 or 22 June, which were treated as "disinformation". The Lucy spy ring in Switzerland also sent warnings, possibly deriving from Ultra codebreaking in Britain. Sweden had access to internal German communications through breaking the crypto used in the Siemens and Halske T52 crypto machine also known as the Geheimschreiber and informed Stalin about the forthcoming invasion well ahead of June 22, but did not reveal its sources.

Soviet intelligence was fooled by German disinformation, so sent false alarms to Moscow about a German invasion in April, May and the beginning of June. Soviet intelligence reported that Germany would rather invade the USSR after the fall of the British Empire[47] or after an unacceptable ultimatum demanding German occupation of Ukraine during the German invasion of Brita

Photo Bikini 18

Female Dick

Dildo Cum Com

Porn Gif Creampie

Young Girl Erotic Film

Eastern Front (World War II) - Wikipedia

BBC - History - World Wars: The Soviet-German War 1941 - 1945

German-Soviet War | Thousand-Week Reich Wiki | Fandom

Soviet-German War - Articles about the largest military ...

Germany–Soviet Union relations, 1918–1941 - Wikipedia

Why the War Between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia Wa…

German-Soviet War - zxc.wiki

German Soviet War

/GettyImages-96830811-c142075c0c9f42f79bb97e6e0e443f71.jpg)