German Letters

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

(Redirected from German alphabet)

For the international agreement about spelling rules among most German-speaking countries, see German orthography reform of 1996.

This article is missing information about punctuation. (June 2019)

This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters.

German orthography is the orthography used in writing the German language, which is largely phonemic. However, it shows many instances of spellings that are historic or analogous to other spellings rather than phonemic. The pronunciation of almost every word can be derived from its spelling once the spelling rules are known, but the opposite is not generally the case.

Today, Standard High German orthography is regulated by the Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung (Council for German Orthography), composed of representatives from most German-speaking countries.

(Listen to a German speaker recite the alphabet in German)

Problems playing this file? See media help.

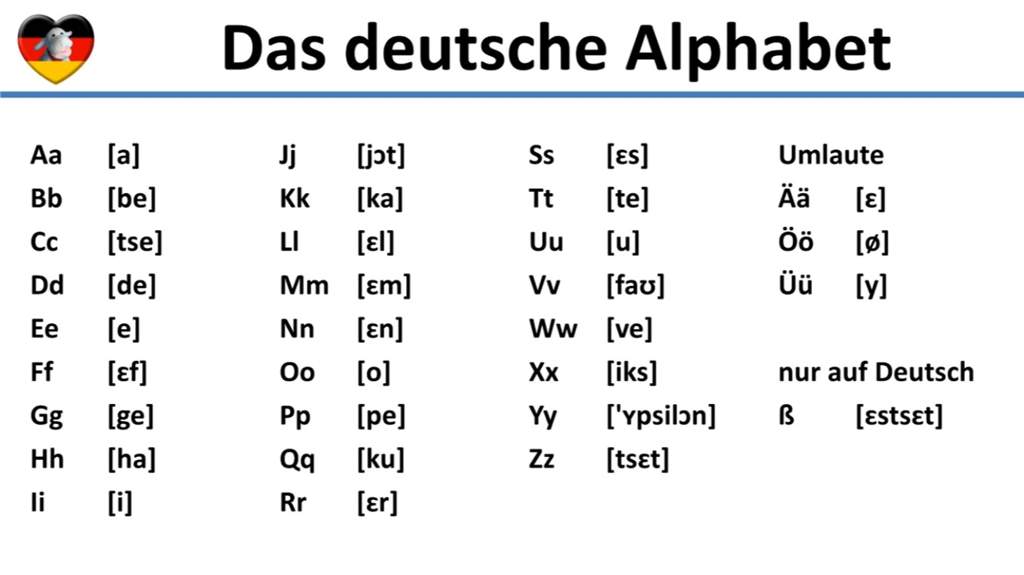

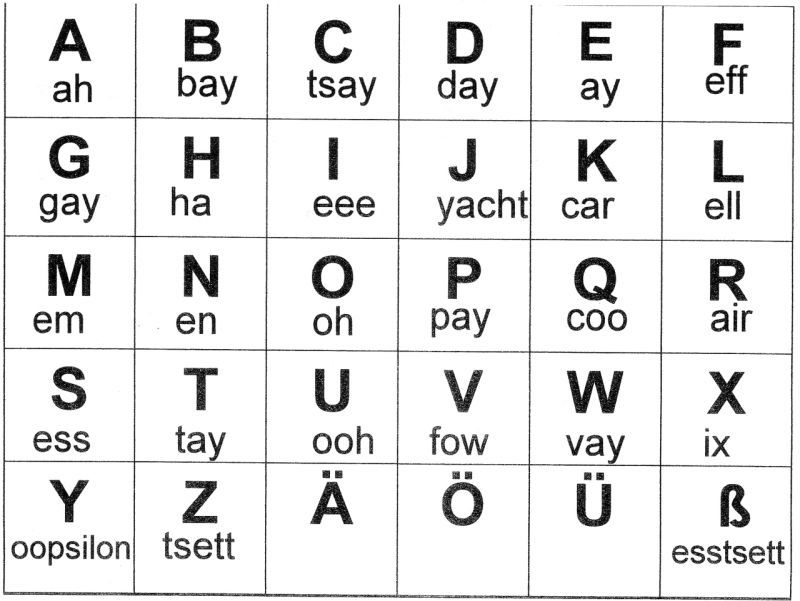

The modern German alphabet consists of the twenty-six letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet plus four special letters.

German uses three letter-diacritic combinations (Ä/ä, Ö/ö, Ü/ü) using the umlaut and one ligature (ß (called Eszett (sz) or scharfes S, sharp s)) which are officially considered distinct letters of the alphabet.[1]

(Listen to a German speaker naming these letters)

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Eszett: /ɛsˈt͡sɛt/

scharfes S: /ˈʃaʁfəs ɛs/

While the Council for German Orthography considers Ä/ä, Ö/ö, Ü/ü, and ẞ/ß distinct letters,[1] disagreement on how to categorize and count them has led to a dispute over the exact number of letters the German alphabet has, the number ranging between 26 (special letters are considered variants of A, O, U, and S) and 30 (all special letters are counted separately).[4]

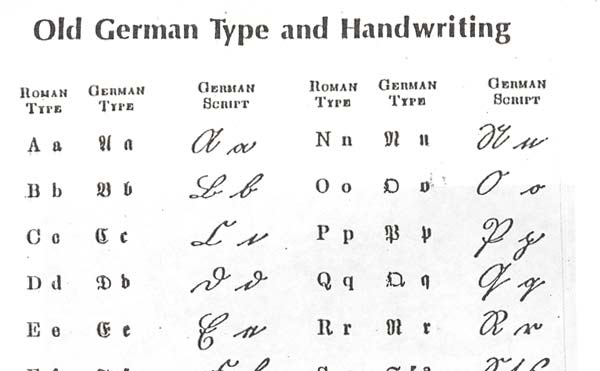

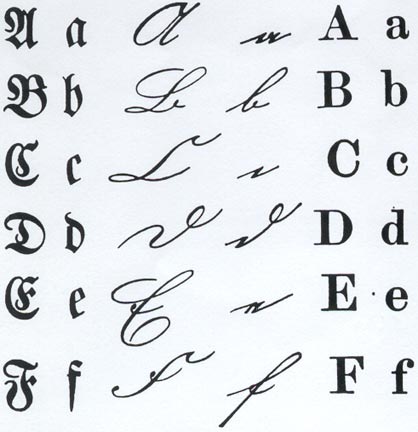

The diacritic letters ä, ö, and ü are used to indicate the presence of umlauts (fronting of back vowels). Before the introduction of the printing press, frontalization was indicated by placing an e after the back vowel to be modified, but German printers developed the space-saving typographical convention of replacing the full e with a small version placed above the vowel to be modified. In German Kurrent writing, the superscripted e was simplified to two vertical dashes (as the Kurrent e consists largely of two short vertical strokes), which have further been reduced to dots in both handwriting and German typesetting. Although the two dots of umlaut look like those in the diaeresis (trema), the two have different origins and functions.

When it is not possible to use the umlauts (for example, when using a restricted character set) the characters Ä, Ö, Ü, ä, ö, ü should be transcribed as Ae, Oe, Ue, ae, oe, ue respectively, following the earlier postvocalic-e convention; simply using the base vowel (e.g. u instead of ü) would be wrong and misleading. However, such transcription should be avoided if possible, especially with names. Names often exist in different variants, such as "Müller" and "Mueller", and with such transcriptions in use one could not work out the correct spelling of the name.

Automatic back-transcribing is not only wrong for names. Consider, for example, das neue Buch ("the new book"). This should never be changed to das neü Buch, as the second e is completely separate from the u and does not even belong in the same syllable; neue ([ˈnɔʏ.ə]) is neu (the root for ‘new’) followed by an e, an inflection. The word neü does not exist in German.

Furthermore, in northern and western Germany, there are family names and place names in which e lengthens the preceding vowel (by acting as a Dehnungs-e), as in the former Dutch orthography, such as Straelen, which is pronounced with a long a, not an ä. Similar cases are Coesfeld and Bernkastel-Kues.

In proper names and ethnonyms, there may also appear a rare ë and ï, which are not letters with an umlaut, but a diaeresis, used as in French to distinguish what could be a digraph, for example, ai in Karaïmen, eu in Alëuten, ie in Piëch, oe in von Loë and Hoëcker (although Hoëcker added the diaeresis himself), and ue in Niuë.[5] Occasionally, a diaeresis may be used in some well-known names, i.e.: Italiën[6] (usually written as Italien).

Swiss keyboards and typewriters do not allow easy input of uppercase letters with umlauts (nor ß) because their positions are taken by the most frequent French diacritics. Uppercase umlauts were dropped because they are less common than lowercase ones (especially in Switzerland). Geographical names in particular are supposed to be written with A, O, U plus e, except Österreich. The omission can cause some inconvenience, since the first letter of every noun is capitalized in German.

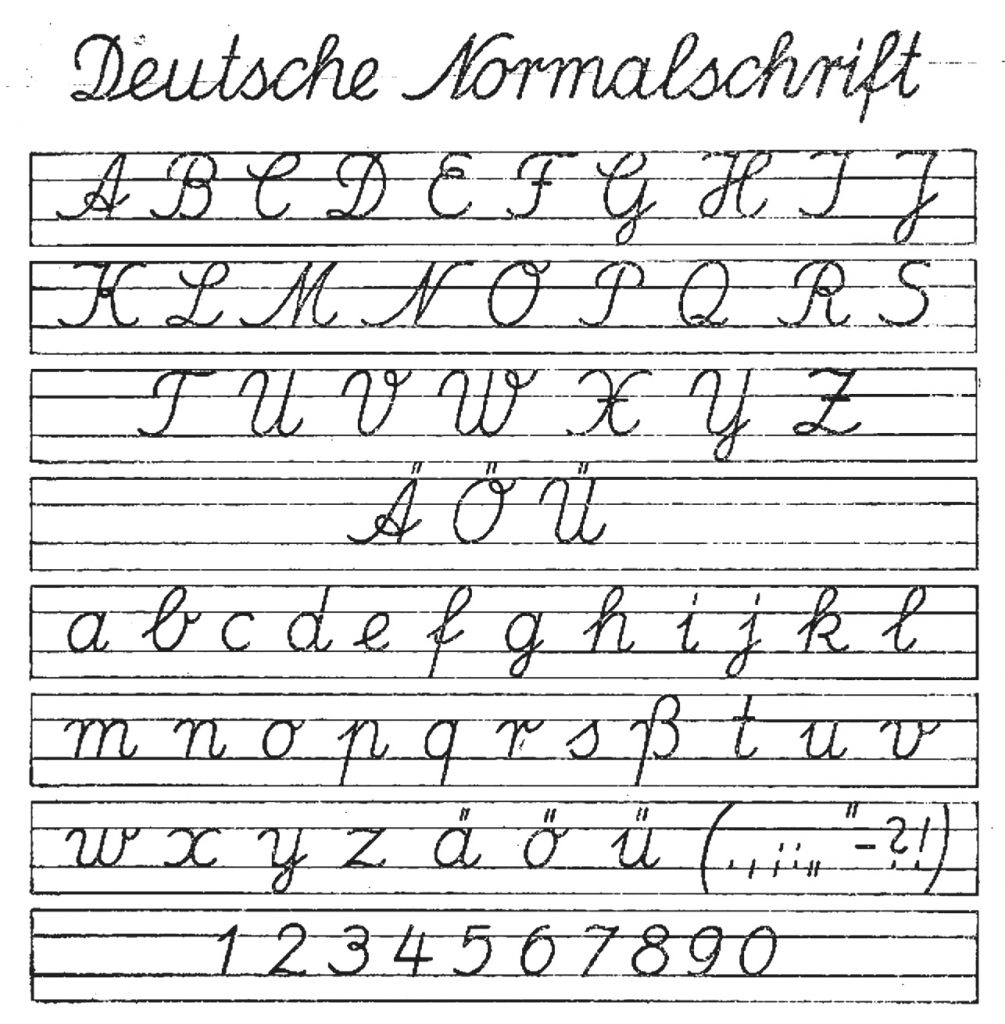

Unlike in Hungarian, the exact shape of the umlaut diacritics – especially when handwritten – is not important, because they are the only ones in the language (not counting the tittle on i and j). They will be understood whether they look like dots (¨), acute accents (˝) or vertical bars (‖). A horizontal bar (macron, ¯), a breve (˘), a tiny N or e, a tilde (˜), and such variations are often used in stylized writing (e.g. logos). However, the breve – or the ring (°) – was traditionally used in some scripts to distinguish a u from an n. In rare cases, the n was underlined. The breved u was common in some Kurrent-derived handwritings; it was mandatory in Sütterlin.

The eszett or scharfes S (ẞ, ß) represents the unvoiced s sound. The German spelling reform of 1996 somewhat reduced usage of this letter in Germany and Austria. It is not used in Switzerland and Liechtenstein.

As the ß derives from a ligature of lowercase letters, it is exclusively used in the middle or at the end of a word. The proper transcription when it cannot be used is ss (sz and SZ in earlier times). This transcription can give rise to ambiguities, albeit rarely; one such case is in Maßen (in moderation) vs. in Massen (en masse). In all-caps, ß is replaced by SS or, optionally, by the uppercase ẞ.[7] The uppercase ẞ was included in Unicode 5.1 as U+1E9E in 2008. Since 2010 its use is mandatory in official documentation in Germany when writing geographical names in all-caps.[8] The option of using the uppercase ẞ in all-caps was officially added to the German orthography in 2017.[9]

Although nowadays substituted correctly only by ss, the letter actually originates from a distinct ligature: long s with (round) z ("ſz"/"ſʒ"). Some people therefore prefer to substitute "ß" by "sz", as it can avoid possible ambiguities (as in the above "Maßen" vs "Massen" example).

Incorrect use of the ß letter is a common type of spelling error even among native German writers. The spelling reform of 1996 changed the rules concerning ß and ss (no forced replacement of ss to ß at word’s end). This required a change of habits and is often disregarded: some people even incorrectly assumed that the "ß" had been abolished completely. However, if the vowel preceding the s is long, the correct spelling remains ß (as in Straße). If the vowel is short, it becomes ss, e.g. "Ich denke, dass…" (I think that…). This follows the general rule in German that a long vowel is followed by a single consonant, while a short vowel is followed by a double consonant.

This change towards the so-called Heyse spelling, however, introduced a new sort of spelling error, as the long/short pronunciation differs regionally. It was already mostly abolished in the late 19th century (and finally with the first unified German spelling of 1901) in favor of the Adelung spelling. Besides the long/short pronunciation issue, which can be attributed to dialect speaking (for instance, in the northern parts of Germany Spaß is typically pronounced short, i.e. Spass, whereas particularly in Bavaria elongated may occur as in Geschoss which is pronounced Geschoß in certain regions), Heyse spelling also introduces reading ambiguities that do not occur with Adelung spelling such as Prozessorientierung (Adelung: Prozeßorientierung) vs. "Prozessorarchitektur" (Adelung: Prozessorarchitektur). It is therefore recommended to insert hyphens where required for reading assistance, i.e. Prozessor-Architektur vs. Prozess-Orientierung.

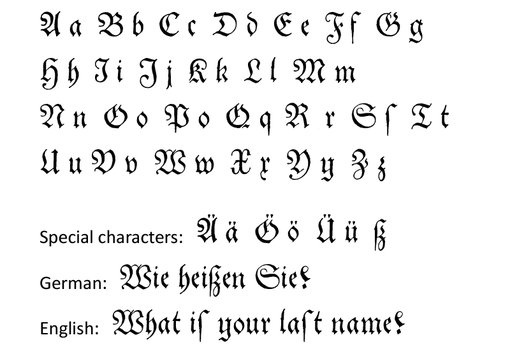

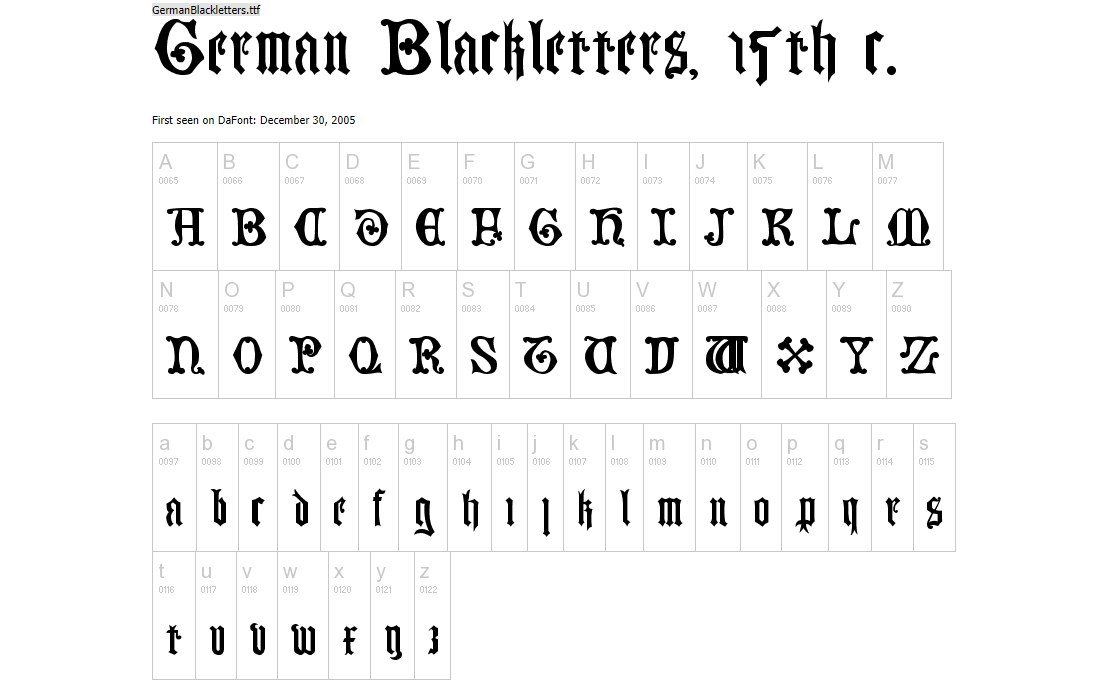

In the Fraktur typeface and similar scripts, a long s (ſ) was used except in syllable endings (cf. Greek sigma) and sometimes it was historically used in antiqua fonts as well; but it went out of general use in the early 1940s along with the Fraktur typeface. An example where this convention would avoid ambiguity is Wachstube, which was written either Wachſtube = Wach-Stube (IPA: [ˈvax.ʃtuːbə], guardhouse) or Wachstube = Wachs-Tube (IPA: [ˈvaks.tuːbə], tube of wax).

There are three ways to deal with the umlauts in alphabetic sorting.

Microsoft Windows in German versions offers the choice between the first two variants in its internationalisation settings.

A sort of combination of nos. 1 and 2 also exists, in use in a couple of lexica: The umlaut is sorted with the base character, but an ae, oe, ue in proper names is sorted with the umlaut if it is actually spoken that way (with the umlaut getting immediate precedence). A possible sequence of names then would be "Mukovic; Muller; Müller; Mueller; Multmann" in this order.

Eszett is sorted as though it were ss. Occasionally it is treated as s, but this is generally considered incorrect. Words distinguished only by ß vs. ss can only appear in the (presently used) Heyse writing and are even then rare and possibly dependent on local pronunciation, but if they appear, the word with ß gets precedence, and Geschoß (storey; South German pronunciation) would be sorted before Geschoss (projectile).

Accents in French loanwords are always ignored in collation.

In rare contexts (e.g. in older indices) sch (phonetic value equal to English sh) and likewise st and ch are treated as single letters, but the vocalic digraphs ai, ei (historically ay, ey), au, äu, eu and the historic ui and oi never are.

German names containing umlauts (ä, ö, ü) and/or ß are spelled in the correct way in the non-machine-readable zone of the passport, but with AE, OE, UE and/or SS in the machine-readable zone, e.g. Müller becomes MUELLER, Weiß becomes WEISS, and Gößmann becomes GOESSMANN. The transcription mentioned above is generally used for aircraft tickets et cetera, but sometimes (like in US visas) simple vowels are used (MULLER, GOSSMANN). As a result, passport, visa, and aircraft ticket may display different spellings of the same name. The three possible spelling variants of the same name (e.g. Müller / Mueller / Muller) in different documents sometimes lead to confusion, and the use of two different spellings within the same document may give persons unfamiliar with German orthography the impression that the document is a forgery.

Even before the introduction of the capital ẞ, it was recommended to use the minuscule ß as a capital letter in family names in documents (e.g. HEINZ GROßE, today's spelling: HEINZ GROẞE).

German naming law accepts umlauts and/or ß in family names as a reason for an official name change. Even a spelling change, e.g. from Müller to Mueller or from Weiß to Weiss is regarded as a name change.

A typical feature of German spelling is the general capitalization of nouns and of most nominalized words.

Compound words, including nouns, are written together, e.g. Haustür (Haus + Tür; "house door"), Tischlampe (Tisch + Lampe; "table lamp"), Kaltwasserhahn (Kalt + Wasser + Hahn; "cold water tap/faucet"). This can lead to long words: the longest word in regular use, Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften[10] ("legal protection insurance companies"), consists of 39 letters.

Even though vowel length is phonemic in German, it is not consistently represented. However, there are different ways of identifying long vowels:

Even though German does not have phonemic consonant length, there are many instances of doubled or even tripled consonants in the spelling. A single consonant following a checked vowel is doubled if another vowel follows, for instance immer 'always', lassen 'let'. These consonants are analyzed as ambisyllabic because they constitute not only the syllable onset of the second syllable but also the syllable coda of the first syllable, which must not be empty because the syllable nucleus is a checked vowel.

By analogy, if a word has one form with a doubled consonant, all forms of that word are written with a doubled consonant, even if they do not fulfill the conditions for consonant doubling; for instance, rennen 'to run' → er rennt 'he runs'; Küsse 'kisses' → Kuss 'kiss'.

Even though German does not have phonemic consonant length, long consonants can occur in composite words when the first part ends in the same consonant the second part starts with, e.g. in the word Schaffell ('sheepskin', composed of Schaf 'sheep' and Fell 'skin, fur, pelt').

Composite words can also have tripled letters. While this is usually a sign that the consonant is actually spoken long, it does not affect the pronunciation per se: the fff in Sauerstoffflasche ('oxygen bottle', composed of Sauerstoff 'oxygen' and Flasche 'bottle') is exactly as long as the ff in Schaffell. According to the spelling before 1996, the three consonants would be shortened before vowels, but retained before consonants and in hyphenation, so the word Schifffahrt ('navigation, shipping', composed of Schiff 'ship' and Fahrt 'drive, trip, tour') was then written Schiffahrt, whereas Sauerstoffflasche already had a triple fff. With the aforementioned change in ß spelling, even a new source of triple consonants sss, which in pre-1996 spelling could not occur as it was rendered ßs, was introduced, e. g. Mussspiel ('compulsory round' in certain card games, composed of muss 'must' and Spiel 'game').

For technical terms, the foreign spelling is often retained such as ph /f/ or y /yː/ in the word Physik (physics) of Greek origin. For some common affixes however, like -graphie or Photo-, it is allowed to use -grafie or Foto- instead.[11] Both Photographie and Fotografie are correct, but the mixed variants Fotographie or Photografie are not.[11]

For other foreign words, both the foreign spelling and a revised German spelling are correct such as Delphin / Delfin[12] or Portemonnaie / Portmonee, though in the latter case the revised one does not usually occur.[13]

For some words for which the Germanized form was common even before the reform of 1996, the foreign version is no longer allowed. A notable example is the word Foto, with the meaning “photograph”, which may no longer be spelled as Photo.[14] Other examples are Telephon (telephone) which was already Germanized as Telefon some decades ago or Bureau (office) which got replaced by the Germanized version Büro even earlier.

Except for the common sequences sch (/ʃ/), ch ([x] or [ç]) and ck (/k/) the letter c appears only in loanwords or in proper nouns. In many loanwords, including most words of Latin origin, the letter c pronounced (/k/) has been replaced by k. Alternatively, German words which come from Latin words with c before e, i, y, ae, oe are usually pronounced with (/ts/) and spelled with z. However, certain older spellings occasionally remain, mostly for decorative reasons, such as Circus instead of Zirkus.

The letter q in German appears only in the sequence qu (/kv/) except for loanwords such as Coq au vin or Qigong (the latter is also written Chigong).

The letter x (Ix, /ɪks/) occurs almost exclusively in loanwords such as Xylofon (xylophone) and names, e.g. Alexander and Xanthippe. Native German words now pronounced with a /ks/ sound are usually written using chs or (c)ks, as with Fuchs (fox). Some exceptions occur such as Hexe (witch), Nixe (mermaid), Axt (axe) and Xanten.

The letter y (Ypsilon, /ˈʏpsilɔn/) occurs almost exclusively in loanwords, especially words of Greek origin, but some such words (such as Typ) have become so common that they are no longer perceived as foreign. It used to be more common in earlier centuries, and traces of this earlier usage persist in proper names. It is used either as an alternative letter for i, for instance in Mayer / Meyer (a common family name that occurs also in the spellings Maier / Meier), or especially in the Southwest, as a representation of [iː] that goes back to an old IJ (digraph), for instance in Schwyz or Schnyder (an Alemannic variant of the name Schneider).[citation needed] Another notable exception is Bayern ("Bavaria") and derived words like bayrisch ("Bavarian"); this actually used to be spelt with an i until the King of Bavaria introduced the y as a sign of his philhellenism (his son would become King of Greece later).

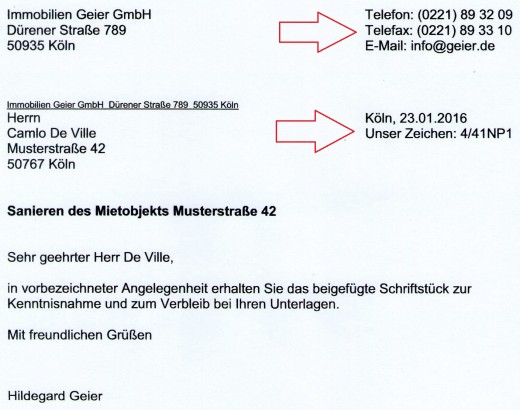

In loan words from the French language, spelling and accents are usually preserved. For instance, café in the sense of "coffeehouse" is always written Café in German; accentless Cafe would be considered erroneous, and the word cannot be written Kaffee, which means "coffee". Thus, German typewriters and computer keyboards offer two dead keys: one for the acute and grave accents and one for circumflex. Other letters occur less often such as ç in loan words from French or Portuguese, and ñ in loan words from Spanish.

In one curious instance, the word Ski (meaning as in English) is pronounced as if it were Schi all over the German-speaking areas (reflecting its pronunciation in its source language Norwegian), but only written that way in Austria.[15]

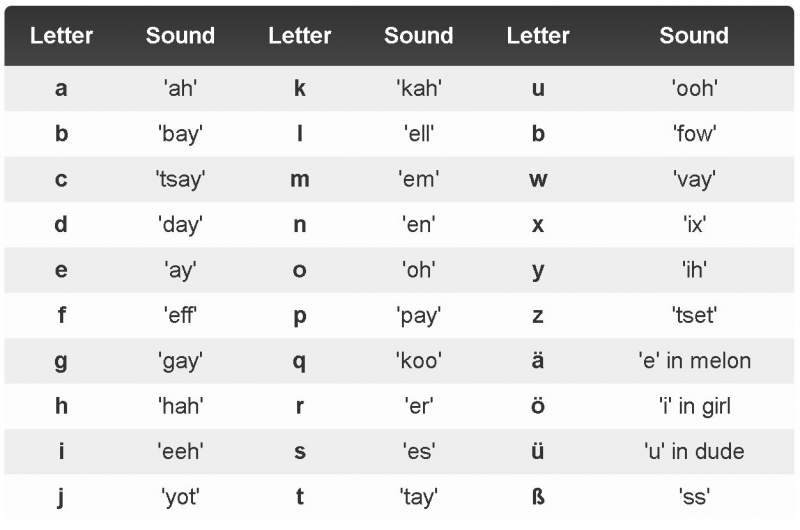

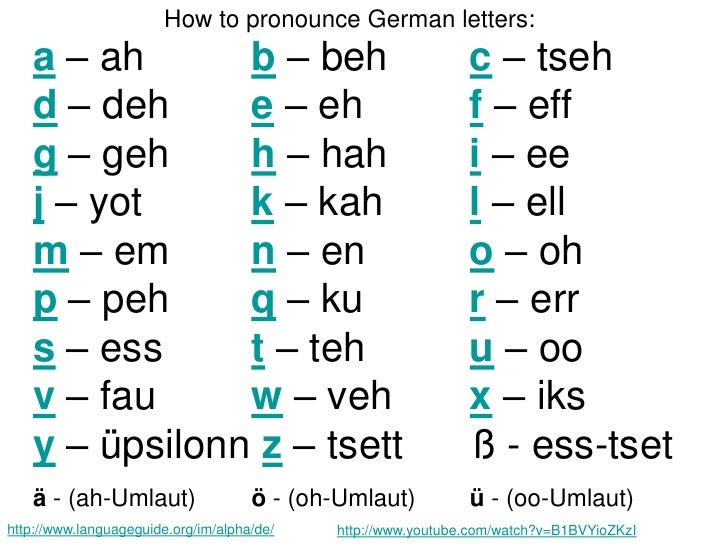

This section lists German letters and letter combinations, and how to pronounce them transliterated into the International Phonetic Alphabet. This is the pronunciation of Standard German. Note that the pronunciation of standard German varies slightly from region to region. In fact, it is possible to tell where most German speakers come from by their accent in standard German (not to be confused with the different German dialects).

Foreign words are usually pronounced approximately as they are in the original language.

Double consonants are pronounced as single consonants, except in compound words.

Consonants are sometimes doubled in writing to indicate the preceding vowel is to be pronounced as a short vowel. Most one-syllable words that end in a single consonant are pronounced with long vowels, but there are some exceptions such as an, das, es, in, mit, and von. The e in the ending -en is often silent, as in bitten "to ask, request". The ending -er is often pronounced [ɐ], but in some regions, people say [ʀ̩] or [r̩]. The e in the ending -el ([əl ~ l̩], e.g. Tunnel, Mörtel "mortar") is pronounced short despite having just a single consonant on the end.

A vowel usually represents a long sound if the vowel in question occurs:

Long vowels are generally pronounced with greater tenseness than short vo

Top Female

Super Milf Moms

Couples Fuck Together

Christmas Couple

Russian Bikini

German orthography - Wikipedia

Learning the Alphabet in German

Type German letters - online German keyboard

German/Grammar/Alphabet and Pronunciation - Wikibooks ...

The German Alphabet (das deutsche Alphabet)

German Letters