German Gothic

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Highlights of Germany | Gothic Germany

www.odysseytraveller.com/articles/gothi…

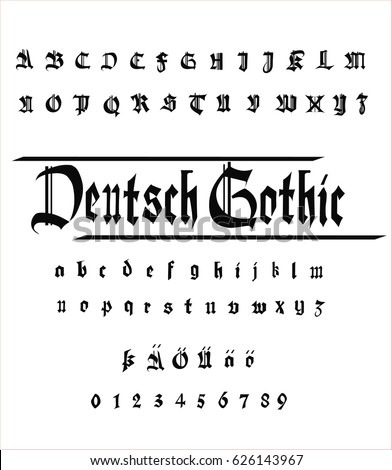

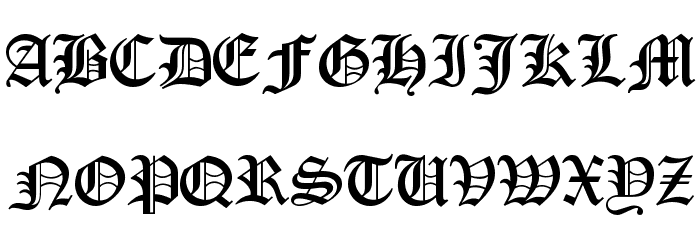

Which is the best website for German gothic fonts?

Which is the best website for German gothic fonts?

The best website for free high-quality German Gothic fonts, with 24 free German Gothic fonts for immediate download, and ➔ 74 professional German Gothic fonts for the best price on the Web. Show 26 similar free German Gothic fonts… Instant downloads for 30 free gothic, german fonts. For you professionals, 9 are 100% free for commercial-use!

Which is the first Gothic church in Germany?

Which is the first Gothic church in Germany?

Here are some examples of German Gothic sites you can visit today. The Liebfrauenkirche in Trier, a southwestern German city in the Moselle wine region near the Luxembourg border, is considered to be the earliest Gothic church in Germany, alongside the Cathedral of Magdeburg (reportedly begun in 1209, but finished after the Liebfrauenkirche).

www.odysseytraveller.com/articles/gothic …

Gothic style started in France around 1140. It gradually found its way to Germany, where the Romanesque style lingered. When Gothic arrived, it filtered first into places like Trier and Heidelberg that were closer to France. The first major German gothic work was Strasbourg Cathedral, built in the second half of the 13th century.

study.com/academy/lesson/german-gothi…

Which is a feature of the German Gothic style?

Which is a feature of the German Gothic style?

Another feature of the German Gothic style is hall-churches. In traditional French Gothic churches, the nave, the long central interior section, was covered by one roof and separated from side aisles with thicker supports and a wall.

www.odysseytraveller.com/articles/gothic …

Готическая архитектура — период развития западно и центрально-европейской архитектуры, соответствующий …

Текст из Википедии, лицензия CC-BY-SA

https://study.com/academy/lesson/german-gothic-architecture.html

Gothic Architecture in General

Beginning of German Gothic Architecture

Unique German Gothic Elements

Gothic style started in France around 1140. It gradually found its way to Germany, where the Romanesque style lingered. When Gothic arrived, it filtered first into places like Trier and Heidelberg that were closer to France. The first major German gothic work was Strasbourg Cathedral, built in the second half of the 13th century. It sits in the city of Strasbourg in Als…

https://www.last.fm/ru/tag/german+gothic/artists

Unheilig (читается «унха́йлихь», русск. Нечестивый (грешный, безбожный) — немецкий NDH/Gothic/Industrial Metal проект, образованный в 1999 году…

https://www.odysseytraveller.com/articles/gothic-germany

Перевести · 08.01.2020 · Highlights of Germany | Gothic Germany The Liebfrauenkirche (Church of Our Beloved Lady) in Trier. The Liebfrauenkirche in …

https://www.free-fonts.com/german-gothic

Перевести · The best website for free high-quality German Gothic fonts, with 24 free German Gothic fonts for immediate download, and 74 professional German Gothic fonts for …

V/A 1997 Godfathers Of German Gothic Vol. III

Allies Break Through the German Gothic Line | World War 2 Documentary | 1963

DIRTY SECRETS of WW2: The German Gothic Line

YouTube › East Tennessee State University

Gothic 3 speedrun (no major glitches)

German Gothic Architecture and Sculpture

YouTube › East Tennessee State University

https://www.architecturecourses.org/germany-gothic-architecture

Перевести · Germany Gothic Architecture. During the 15th century Germany experimented with Medieval Architecture designs. German architects worked with …

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gothic_language

Dialects: Crimean Gothic

Era: attested 3rd–10th century; related …

Language family: Indo-European, …

Writing system: Gothic alphabet

It is possible to determine more or less exactly how the Gothic of Ulfilaswas pronounced, primarily through comparative phonetic reconstruction. Furthermore, because Ulfilas tried to follow the original Greek text as much as possible in his translation, it is known that he used the same writing conventions as those of contemporary Greek. Since the Greek of that period is well documented, it is possible to reconstruct much of Gothic pronu…

It is possible to determine more or less exactly how the Gothic of Ulfilas was pronounced, primarily through comparative phonetic reconstruction. Furthermore, because Ulfilas tried to follow the original Greek text as much as possible in his translation, it is known that he used the same writing conventions as those of contemporary Greek. Since the Greek of that period is well documented, it is possible to reconstruct much of Gothic pronunciation from translated texts. In addition, the way in which non-Greek names are transcribed in the Greek Bible and in Ulfilas's Bible is very informative.

Vowels

• /a/, /i/ and /u/ can be either long or short. Gothic writing distinguishes between long and short vowels only for /i/ by writing i for the short form and ei for the long (a digraph or false diphthong), in an imitation of Greek usage (ει = /iː/). Single vowels are sometimes long where a historically present nasal consonant has been dropped in front of an /h/ (a case of compensatory lengthening). Thus, the preterite of the verb briggan [briŋɡan] "to bring" (English bring, Dutch brengen, German bringen) becomes brahta [braːxta] (English brought, Dutch bracht, German brachte), from Proto-Germanic *branhtē. In detailed transliteration, when the intent is more phonetic transcription, length is noted by a macron (or failing that, often a circumflex): brāhta, brâhta. This is the only context in which /aː/ appears natively whereas /uː/, like /iː/, is found often enough in other contexts: brūks "useful" (Dutch gebruik, German Gebrauch, Icelandic brúk "use").

• /eː/ and /oː/ are long close-mid vowels. They are written as e and o: neƕ [neːʍ] "near" (English nigh, Dutch nader, German nah); fodjan [foːdjan] "to feed".

• /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ are short open-mid vowels. They are noted using the digraphs ai and au: taihun [tɛhun] "ten" (Dutch tien, German zehn, Icelandic tíu), dauhtar [dɔxtar] "daughter" (Dutch dochter, German Tochter, Icelandic dóttir). In transliterating Gothic, accents are placed on the second vowel of these digraphs aí and aú to distinguish them from the original diphthongs ái and áu: taíhun, daúhtar. In most cases short [ɛ] and [ɔ] are allophones of /i, u/ before /r, h, ʍ/. Furthermore, the reduplication syllable of the reduplicating preterites has ai as well, which was probably pronounced as a short [ɛ]. Finally, short [ɛ] and [ɔ] occur in loan words from Greek and Latin (aípiskaúpus [ɛpiskɔpus] = ἐπίσκοπος "bishop", laíktjo [lɛktjoː] = lectio "lection", Paúntius [pɔntius] = Pontius).

• The Germanic diphthongs /ai/ and /au/ appear as digraphs written ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ in Gothic. Researchers have disagreed over whether they were still pronounced as diphthongs /ai̯/ and /au̯/ in Ulfilas's time (4th century) or had become long open-mid vowels: /ɛː/ and /ɔː/: ains [ains] / [ɛːns] "one" (German eins, Icelandic einn), augo [auɣoː] / [ɔːɣoː] "eye" (German Auge, Icelandic auga). It is most likely that the latter view is correct, as it is indisputable that the digraphs ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ represent the sounds /ɛː/ and /ɔː/ in some circumstances (see below), and ⟨aj⟩ and ⟨aw⟩ were available to unambiguously represent the sounds /ai̯/ and /au̯/. The digraph ⟨aw⟩ is in fact used to represent /au/ in foreign words (such as Pawlus "Paul"), and alternations between ⟨ai⟩/⟨aj⟩ and ⟨au⟩/⟨aw⟩ are scrupulously maintained in paradigms where both variants occur (e.g. taujan "to do" vs. past tense tawida "did"). Evidence from transcriptions of Gothic names into Latin suggests that the sound change had occurred very recently when Gothic spelling was standardized: Gothic names with Germanic au are rendered with au in Latin until the 4th century and o later on (Austrogoti > Ostrogoti). The digraphs ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨au⟩ are normally written with an accent on the first vowel (ái, áu) when they correspond to Proto-Germanic /ai̯/ and /au̯/.

• Long [ɛː] and [ɔː] also occur as allophones of /eː/ and /uː, oː/ respectively before a following vowel: waian [wɛːan] "to blow" (Dutch waaien, German wehen), bauan [bɔːan] "to build" (Dutch bouwen, German bauen, Icelandic búa "to live, reside"), also in Greek words Trauada "Troad" (Gk. Τρῳάς). In detailed transcription these are notated ai, au.

• /y/ (pronounced like German ü and French u) is a Greek sound used only in borrowed words. It is transliterated as w (as it uses the same letter that otherwise denoted the consonant /w/): azwmus [azymus] "unleavened bread" ( < Gk. ἄζυμος). It represents an υ (y) or the diphthong οι (oi), both of which were pronounced [y] in the Greek of the time. Since the sound was foreign to Gothic, it was perhaps pronounced [i].

• /iu/ is a falling diphthong ([iu̯]: diups [diu̯ps] "deep" (Dutch diep, German tief, Icelandic djúpur).

• Greek diphthongs: In Ulfilas's era, all the diphthongs of Classical Greek had become simple vowels in speech (monophthongization), except for αυ (au) and ευ (eu), which were probably still pronounced [aβ] and [ɛβ]. (They evolved into [av~af] and [ev~ef] in Modern Greek.) Ulfilas notes them, in words borrowed from Greek, as aw and aiw, probably pronounced [au̯, ɛu̯]: Pawlus [pau̯lus] "Paul" (Gk. Παῦλος), aíwaggelista [ɛwaŋɡeːlista] "evangelist" (Gk. εὐαγγελιστής, via the Latin evangelista).

• All vowels (including diphthongs) can be followed by a [w], which was likely pronounced as the second element of a diphthong with roughly the sound of [u̯]. It seems likely that this is more of an instance of phonetic juxtaposition than of true diphthongs (such as, for example, the sound /aj/ in the French word paille ("straw"), which is not the diphthong /ai̯/ but rather a vowel followed by an approximant): alew [aleːw] "olive oil" ( < Latin oleum), snáiws [snɛːws] ("snow"), lasiws [lasiws] "tired" (English lazy).

Consonants

In general, Gothic consonants are devoiced at the ends of words. Gothic is rich in fricative consonants (although many of them may have been approximants; it is hard to separate the two) derived by the processes described in Grimm's law and Verner's law and characteristic of Germanic languages. Gothic is unusual among Germanic languages in having a /z/ phoneme, which has not become /r/ through rhotacization. Furthermore, the doubling of written consonants between vowels suggests that Gothic made distinctions between long and short, or geminated consonants: atta [atːa] "dad", kunnan [kunːan] "to know" (Dutch kennen, German kennen "to know", Icelandic kunna).

Stops

• The voiceless stops /p/, /t/ and /k/ are regularly noted by p, t and k respectively: paska [paska] "Easter" (from the Greek πάσχα), tuggo [tuŋɡoː] "tongue", kalbo [kalboː] "calf".

• The letter q is probably a voiceless labiovelar stop, /kʷ/, comparable to the Latin qu: qiman [kʷiman] "to come". In later Germanic languages, this phoneme has become either a consonant cluster /kw/ of a voiceless velar stop + a labio-velar approximant (English qu) or a simple voiceless velar stop /k/ (English c, k)

• The voiced stops /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ are noted by the letters b, d and g. Like the other Germanic languages, they occurred in word-initial position, when doubled and after a nasal. In addition, they apparently occurred after other consonants,: arbi [arbi] "inheritance", huzd [huzd] "treasure". (This conclusion is based on their behavior at the end of a word, in which they do not change into voiceless fricatives, unlike when they occur after a vowel.)

• There was probably also a voiced labiovelar stop, /ɡʷ/, which was written with the digraph gw. It occurred after a nasal, e.g. saggws [saŋɡʷs] "song", or long as a regular outcome of Germanic *ww: triggws [triɡʷːs] "faithful" (English true, German treu, Icelandic tryggur).

• Similarly, the letters ddj, which is the regular outcome of Germanic *jj, may represent a voiced palatal stop, /ɟː/: waddjus [waɟːus] "wall" (Icelandic veggur), twaddje [twaɟːeː] "two (genitive)" (Icelandic tveggja).

Fricatives

• /s/ and /z/ are usually written s and z. The latter corresponds to Germanic *z (which has become r or silent in the other Germanic languages); at the end of a word, it is regularly devoiced to s. E.g. saíhs [sɛhs] "six", máiza [mɛːza] "greater" (English more, Dutch meer, German mehr, Icelandic meira) versus máis [mɛːs] "more, rather".

• /ɸ/ and /θ/, written f and þ, are voiceless bilabial and voiceless dental fricatives respectively. It is likely that the relatively unstable sound /ɸ/ became /f/. f and þ are also derived from b and d at the ends of words and then are devoiced and become approximants: gif [ɡiɸ] "give (imperative)" (infinitive giban: German geben), miþ [miθ] "with" (Old English mid, Old Norse með, Dutch met, German mit). The cluster /ɸl/ became /θl/: þlauhs "flight" from Germanic *flugiz; þliuhan "flee" from Germanic *fleuhaną. This sound change is unique among Germanic languages.

• /h/ is written as h: haban "to have". It was probably pronounced [h] in word-final position and before a consonant as well (not [x], since /ɡ/ > [x] is written g, not h): jah [jah] "and" (Dutch, German, Scandinavian ja "yes").

• [x] is an allophone of /ɡ/ at the end of a word or before a voiceless consonant; it is always written g: dags [daxs] "day" (German Tag). In some borrowed Greek words is the special letter x, which represents the Greek letter χ (ch): Xristus [xristus] "Christ" (Gk. Χριστός). It may also have signified a /k/.

• [β], [ð] and [ɣ] are voiced fricative found only in between vowels. They are allophones of /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ and are not distinguished from them in writing. [β] may have become /v/, a more stable labiodental form. In the study of Germanic languages, these phonemes are usually transcribed as ƀ, đ and ǥ respectively: haban [haβan] "to have", þiuda [θiu̯ða] "people" (Dutch Diets, German Deutsch, Icelandic þjóð > English Dutch), áugo [ɔːɣoː] "eye" (English eye, Dutch oog, German Auge, Icelandic auga). When occurring after a vowel at the end of a word or before a voiceless consonant, these sounds become unvoiced [ɸ], [θ] and [x], e.g. hláifs [hlɛːɸs] "loaf" but genitive hláibis [hlɛːβis] "of a loaf", plural hláibōs [hlɛːβoːs] "loaves".

• ƕ (also transcribed hw) is the labiovelar equivalent of /x/, derived from Proto-Indo-European *kʷ. It was probably pronounced [ʍ] (a voiceless [w]), as wh is pronounced in certain dialects of English and in Scots: ƕan /ʍan/ "when", ƕar /ʍar/ "where", ƕeits [ʍiːts] "white".

Sonorants

Gothic has three nasal consonants, one of which is an allophone of the others, all found only in complementary distribution with them. Nasals in Gothic, like most other languages, are pronounced at the same point of articulation as the consonant that follows them (assimilation). Therefore, clusters like [md] and [nb] are not possible.

• /n/ and /m/ are freely distributed and so can be found in any position in a syllable and form minimal pairs except in certain contexts where they are neutralized: /n/ before a bilabial consonant becomes [m], while /m/ preceding a dental stop becomes [n], as per the principle of assimilation described in the previous paragraph. In front of a velar stop, they both become [ŋ]. /n/ and /m/ are transcribed as n and m, and, in writing, neutralisation is marked: sniumundo /sniu̯mundoː/ ("quickly").

• [ŋ] is not a phoneme and cannot appear freely in Gothic. It is present where a nasal consonant is neutralised before a velar stop and is in a complementary distribution with /n/ and /m/. Following Greek conventions, it is normally written as g (sometimes n): þagkjan [θaŋkjan] "to think", sigqan [siŋkʷan] "to sink" ~ þankeiþ [θaŋkiːθ] "thinks". The cluster ggw sometimes denotes [ŋɡʷ], but sometimes [ɡʷː] (see above).

• /w/ is transliterated as w before a vowel: weis [wiːs] ("we"), twái [twai] "two" (German zwei).

• /j/ is written as j: jer [jeːr] "year", sakjo [sakjoː] "strife".

• /l/ and /r/ occur as in other European languages: laggs (possibly [laŋɡs], [laŋks] or [laŋɡz]) "long", mel [meːl] "hour" (English meal, Dutch maal, German Mahl, Icelandic mál). The exact pronunciation of /r/ is unknown, but it is usually assumed to be a trill [r] or a flap [ɾ]): raíhts [rɛxts] "right", afar [afar] "after".

• /l/, /m/, /n/ and /r/ may occur either between two other consonants of lower sonority or word-finally after a consonant of lower sonority. It is probable that the sounds are pronounced partly or completely as syllabic consonants in such circumstances (as in English "bottle" or "bottom"): tagl [taɣl̩] or [taɣl] "hair" (English tail, Icelandic tagl), máiþms [mɛːθm̩s] or [mɛːθms] "gift", táikns [tɛːkn̩s] or [tɛːkns] "sign" (English token, Dutch teken, German Zeichen, Icelandic tákn) and tagr [taɣr̩] or [taɣr] "tear (as in crying)".

Accentuation and intonation

Accentuation in Gothic can be reconstructed through phonetic comparison, Grimm's law and Verner's law. Gothic used a stress accent rather than the pitch accent of Proto-Indo-European. This is indicated by the shortening of long vowels [eː] and [oː] and the loss of short vowels [a] and [i] in unstressed final syllables.

Just as in other Germanic languages, the free moving Proto-Indo-European accent was replaced with one fixed on the first syllable of simple words. Accents do not shift when words are inflected. In most compound words, the location of the stress depends on the type of compound:

• In compounds in which the second word is a noun, the accent is on the first syllable of the first word of the compound.

• In compounds in which the second word is a verb, the accent falls on the first syllable of the verbal component. Elements prefixed to verbs are otherwise unstressed except in the context of separable words (words that can be broken in two parts and separated in regular usage such as separable verbs in German and Dutch). In those cases, the prefix is stressed.

For example, with comparable words from modern Germanic languages:

• Non-compound words: marka [ˈmarka] "border, borderlands" (English march, Dutch mark); aftra [ˈaɸtra] "after"; bidjan [ˈbiðjan] "pray" (Dutch, bidden, German bitten, Icelandic biðja, English bid).

• Compound words:

Comparison to other Germanic languages

Use in Romanticism and the Modern Age

РекламаАпрельская распродажа! Скидка 75%. Моментальная доставка. Более 85.000 отзывов.

Не удается получить доступ к вашему текущему расположению. Для получения лучших результатов предоставьте Bing доступ к данным о расположении или введите расположение.

Не удается получить доступ к расположению вашего устройства. Для получения лучших результатов введите расположение.

Earn Transferable Credit & Get your Degree fast

Stephanie has taught studio art and art history classes to audiences of all ages. She holds a master's degree in Art History.

Have you ever stood in a large cathedral and

Ebony Anal Casting

Bbw Fucking Porn Videos

Skinny Asian Hd

Cfnm Pure Porno

Erotic 6

German Gothic Architecture | Study.com

Топ-исполнители german gothic | Last.fm

Gothic German Architecture | The Definitive Guide ...

Free German Gothic Fonts - Free Fonts

Germany Gothic Architecture | ArchitectureCourses.Org

Gothic language - Wikipedia

German Gothic

.jpg)

%3aformat(jpeg)%3amode_rgb()%3aquality(90)/discogs-images/R-466885-1143759658.jpeg.jpg)

.jpg%3fw%3d400)