German Foreign Policy

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

The history of German foreign policy covers diplomatic developments and international history since 1871.

Before 1871, Prussia was the dominant factor in German affairs, but there were numerous smaller states. The question of excluding or including Austria's influence was settled by the Prussian victory in the Austro-Prussian War in 1866. The unification of Germany was made possible by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, in which the smaller states joined behind Prussia in a smashing victory over France. The German Empire was put together in 1871 by Otto von Bismarck, who dominated German and indeed all of European diplomatic history until he was forced to resign in 1890.

The new German Empire immediately became the dominant diplomatic, political, military and economic force in Europe, although it never had as large a population as Russia. Great Britain continued to dominate the world in naval affairs, international trade, and finance. The Germans tried to catch up in empire building but felt an inferiority complex.

Bismarck felt a strong need to keep France isolated, lest its desire for revenge frustrate his goals, which after 1871 were European peace and stability. When Kaiser Wilhelm removed Bismarck in 1890, German foreign policy became erratic and increasingly isolated, with only Austria-Hungary as a serious ally and partner.

During the July Crisis, Germany played a major role in starting World War I in 1914. The Allies defeated Germany in 1918. The Versailles Peace Treaty was punishing for Germany.

By the mid-1920s, Germany had largely recovered its role as a great power thanks to astute diplomacy on its own part, the willingness of the British and Americans compromise, and financial aid from New York. Internal German politics became frenzied after 1929 and the impact of the Great Depression, leading to a takeover by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis in 1933. They introduced a highly aggressive foreign policy in alliance with Italy and Japan. The British and French tried to appease in 1938, which only whetted Hitler's appetite for more territory, especially in the East. Nazi Germany had by far the most decisive role in starting World War II in 1939.

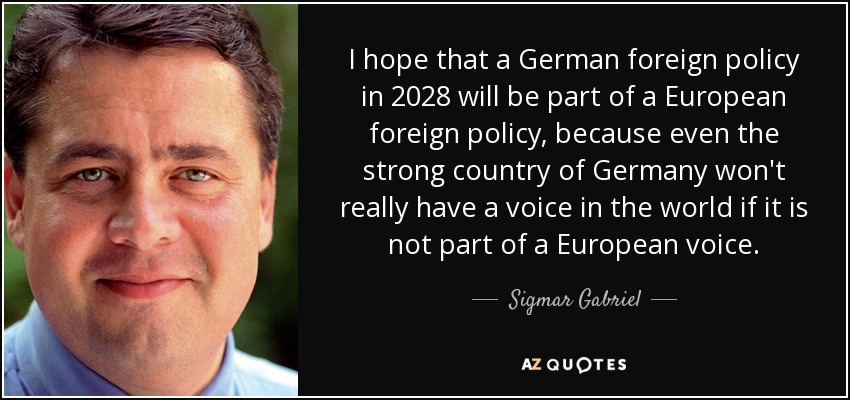

Since 1945, Germany has recovered from massive wartime destruction to become again the richest and most powerful country in Europe, this time it is fully integrated into European affairs. Its major conflict was West Germany versus East Germany, with East Germany being a client state of the Soviet Union until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since the 1970s, (West) Germany has also sought to play a more important role internationally again.[1]

After the creation of the German Empire in 1871, diplomatic relations were handled by the Imperial government, rather than by lower-level governments such as the Prussian and Bavarian governments. Down to 1914, the Chancellor typically dominated foreign policy decisions, supported by his Foreign Minister. The powerful German Army reported separately to the Emperor, and increasingly played a major role in shaping foreign policy when military alliances or warfare was at issue.[2]

In diplomatic terms, Germany used the Prussian system of military attaches attached to diplomatic locations, with highly talented young officers assigned to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, and military capabilities of their assigned nations. These officers used close observation, conversations, and paid agents to produce very high quality reports that gave a significant advantage to the military planners.[3]

The military staff grew increasingly powerful, reducing the role of the Minister of War and increasingly asserting itself in foreign policy decisions. Otto von Bismarck, the Imperial Chancellor from 1871 to 1890, was annoyed by military interference in foreign policy affairs–in 1887, for example, the military tried to convince the Emperor to declare war on Russia; they also encouraged Austria to attack Russia. Bismarck never controlled the army, but he did complain vehemently, and the military leaders drew back. In 1905, when the Morocco affair was roiling international politics, Chief of the German General Staff Alfred von Schlieffen called for a preventive war against France. At a critical point in the July crisis of 1914, Helmuth von Moltke, the Chief of Staff, without telling the Emperor or Chancellor, advised his counterpart in Austria to mobilize against Russia at once. During World War I, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff increasingly set foreign policy, working directly with the Emperor–and indeed shaped his decision-making–leaving the chancellor and civilian officials in the dark. Historian Gordon A. Craig says that the crucial decisions in going to war in 1914, "were made by the soldiers and that, in making them, they displayed an almost complete disregard for political considerations."[4]

Bismarck's post-1871 foreign policy was peace-oriented. Germany was content—it had all it wanted so that its main goal was peace and stability. However, peaceful relations with France became impossible in 1871 when Germany annexed the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. Public opinion demanded it to humiliate France, and the Army wanted its more defensible frontiers. Bismarck reluctantly gave in—French would never forget or forgive, he calculated, so might as well take the provinces. (That was a mistaken assumption—after about five years the French did calm down and considered it a minor issue.)[5]) Germany's foreign policy fell into a trap with no exit. "In retrospect it is easy to see that the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine was a tragic mistake."[6][7] Once the annexation took place the only policy that made sense was trying to isolate France so it had no strong allies. However France complicated Berlin's plans when it became friends with Russia. In 1905 a German plan for an alliance with Russia fell through because Russia was too close to France.[8]

The League of Three Emperors (Dreikaisersbund) was signed in 1872 by Russia, Austria, and Germany. It stated that republicanism and socialism were common enemies and that the three powers would discuss any matters concerning foreign policy. Bismarck needed good relations with Russia in order to keep France isolated. In 1877–1878, Russia fought a victorious war with the Ottoman Empire and attempted to impose the Treaty of San Stefano on it. This upset the British in particular, as they were long concerned with preserving the Ottoman Empire and preventing a Russian takeover of the Bosphorus Strait. Germany hosted the Congress of Berlin (1878), whereby a more moderate peace settlement was agreed to. Germany had no direct interest in the Balkans, however, which was largely an Austrian and Russian sphere of influence, although King Carol of Romania was a German prince.

In 1879, Bismarck formed a Dual Alliance of Germany and Austria-Hungary, with the aim of mutual military assistance in the case of an attack from Russia, which was not satisfied with the agreement reached at the Congress of Berlin. The establishment of the Dual Alliance led Russia to take a more conciliatory stance, and in 1887, the so-called Reinsurance Treaty was signed between Germany and Russia: in it, the two powers agreed on mutual military support in the case that France attacked Germany, or in case of an Austrian attack on Russia. Russia turned its attention eastward to Asia and remained largely inactive in European politics for the next 25 years. In 1882, Italy joined the Dual Alliance to form a Triple Alliance. Italy wanted to defend its interests in North Africa against France's colonial policy. In return for German and Austrian support, Italy committed itself to assisting Germany in the case of a French military attack.[9]

For a long time, Bismarck had refused to give in widespread public and elite demands to give Germany "a place in the sun" through the acquisition of overseas colonies. In 1880 Bismarck gave way, and a number of colonies were established overseas building on private German business ventures. In Africa, these were Togo, the Cameroons, German South-West Africa, and German East Africa; in Oceania, they were German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the Marshall Islands. In fact, it was Bismarck himself who helped initiate the Berlin Conference of 1885. He did it to "establish international guidelines for the acquisition of African territory" (see Colonisation of Africa). This conference was an impetus for the "Scramble for Africa" and "New Imperialism".[10] [11]

After removing Bismarck in 1890 the young Kaiser Wilhelm sought aggressively to increase Germany's influence in the world (Weltpolitik).[12] Foreign policy was in the hands of an erratic Kaiser, who played an increasingly reckless hand,[13] and the powerful foreign office under the leadership of Friedrich von Holstein.[14] The foreign office argued that: first, a long-term coalition between France and Russia had to fall apart; secondly, Russia and Britain would never get together; and, finally, Britain would eventually seek an alliance with Germany. Germany refused to renew its treaties with Russia. But Russia did form a closer relationship with France in the Dual Alliance of 1894, since both were worried about the possibilities of German aggression. Furthermore, Anglo–German relations cooled as Germany aggressively tried to build a new empire and engaged in a naval race with Britain; London refused to agree to the formal alliance that Germany sought. Berlin's analysis proved mistaken on every point, leading to Germany's increasing isolation and its dependence on the Triple Alliance, which brought together Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. The Triple Alliance was undermined by differences between Austria and Italy, and in 1915 Italy switched sides.[15]

Meanwhile, the German Navy under Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz had ambitions to rival the great British Navy, and dramatically expanded its fleet in the early 20th century to protect the colonies and exert power worldwide.[16] Tirpitz started a programme of warship construction in 1898. In 1890, Germany had gained the island of Heligoland in the North Sea from Britain in exchange for the eastern African island of Zanzibar, and proceeded to construct a great naval base there. This posed a direct threat to British hegemony on the seas, with the result that negotiations for an alliance between Germany and Britain broke down. The British, however, kept well ahead in the naval race by the introduction of the highly advanced new Dreadnought battleship in 1907.[17]

In the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905, Germany nearly came to blows with Britain and France when the latter attempted to establish a protectorate over Morocco. The Germans were upset at having not been informed about French intentions, and declared their support for Moroccan independence. William II made a highly provocative speech regarding this. The following year, a conference was held in which all of the European powers except Austria-Hungary (by now little more than a German satellite) sided with France. A compromise was brokered by the United States where the French relinquished some, but not all, control over Morocco.[18]

The Second Moroccan Crisis of 1911 saw another dispute over Morocco erupt when France tried to suppress a revolt there. Germany, still smarting from the previous quarrel, agreed to a settlement whereby the French ceded some territory in central Africa in exchange for Germany's renouncing any right to intervene in Moroccan affairs. It was a diplomatic triumph for France.[19]

Historian Heather Jones argues that Germany's use of warlike rhetoric was a deliberate diplomatic ploy:

The German adventure resulted in failure and frustration, as military cooperation and friendship between France and Britain was strengthened, and Germany was left more isolated. An even more momentous consequence was the heightened sense of frustration and readiness for war in Germany. It spread beyond the political elite to much of the press and most of the political parties except for the Liberals and Social Democrats on the left. The Pan-German element grew in strength and denounced their government's retreat as treason, stepping up chauvinistic support for war.[21]

Ethnic groups demanded their own nation states, threatening violence. This upset the stability of multinational empires (Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, Turkey/Ottoman). When ethnic Serbians assassinate the Austrian heir, Austria decided to heavily punish Serbia. Germany stood behind its ally Austria in a confrontation with Serbia, but Serbia was under the informal protection of Russia, which was allied to France. Germany was the leader of the Central Powers, which included Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and later Bulgaria; arrayed against them were the Allies, consisting chiefly of Russia, France, Britain, and in 1915 Italy.[22]

In explaining why neutral Britain went to war with Germany, Kennedy (1980) recognized it was critical for war that Germany become economically more powerful than Britain, but he downplays the disputes over economic trade imperialism, the Baghdad Railway, confrontations in Central and Eastern Europe, high-charged political rhetoric and domestic pressure-groups. Germany's reliance time and again on sheer power, while Britain increasingly appealed to moral sensibilities, played a role, especially in seeing the invasion of Belgium as a profound moral and diplomatic crime. Kennedy argues that by far the main reason was London's fear that a repeat of 1870 — when Prussia and the German states smashed France — would mean that Germany, with a powerful army and navy, would control the English Channel and northwest France. British policy makers insisted that would be a catastrophe for British security.[23]

The Germans never finalized a set of war aims. However, in September 1914, Kurt Riezler, a senior staff aide to German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg sketched out some possible ideas—dubbed by historians the "September Program." It emphasized economic gains, turning all of Central and Western Europe into a common market controlled by and for the benefit of Germany. Belgium would become a vassal state, there would be a series of naval bases threatening England, Germany would seize much of Eastern Europe from Russia – as in fact it did in early 1918. There would be a crippling financial indemnity on France making it economically dependent on Germany. The Netherlands would become a dependent satellite, and British commerce would be excluded. Germany would rebuild a colonial empire in Africa. The ideas sketched by Riezler were not fully formulated, were not endorsed by Bethmann-Hollweg, and were not presented to or approved by any official body. The ideas were formulated on the run after the war began, and did not mean these ideas had been reflected a prewar plan, as historian Fritz Fischer fallaciously assumed. However they do indicate that if Germany had won it would have taken a very aggressive dominant position in Europe. Indeed, it took a very harsh position on occupied Belgian and France starting in 1914, and in the Treaty of Brest Litovsk imposed on Russia in 1918.[24][25]

The stalemate by the end of 1914 forced serious consideration of long-term goals. Britain, France, Russia and Germany all separately concluded this was not a traditional war with limited goals. Britain, France and Russia became committed to the destruction of German military power, and Germany to the dominance of German military power in Europe. One month into the war, Britain, France and Russia agreed not to make a separate peace with Germany, and discussions began about enticing other countries to join in return for territorial gains. However, as Barbara Jelavich observes, "Throughout the war Russian actions were carried out without real coordination or joint planning with the Western powers."[26] There was no serious three-way coordination of strategy, nor was there much coordination between Britain and France before 1917.

The humiliating peace terms in the Treaty of Versailles provoked bitter indignation throughout Germany, and seriously weakened the new democratic regime since Paul von Hindenburg the president of Weimar Republic used article 48 to gain emergency power hence undermining democracy.

When Germany defaulted on its reparation payments, French and Belgian troops occupied the heavily industrialised Ruhr district (January 1923). The German government encouraged the population of the Ruhr to passive resistance: shops would not sell goods to the foreign soldiers, coal-mines would not dig for the foreign troops, trams in which members of the occupation army had taken seat would be left abandoned in the middle of the street. The passive resistance proved effective, insofar as the occupation became a loss-making deal for the French government. But the Ruhr fight also led to hyperinflation, and many who lost all their fortune would become bitter enemies of the Weimar Republic, and voters of the anti-democratic right. See 1920s German inflation.

Germany was the first state to establish diplomatic relations with the new Soviet Union. Under the Treaty of Rapallo, Germany accorded the Soviet Union de jure recognition, and the two signatories mutually cancelled all pre-war debts and renounced war claims. In October 1925 the Treaty of Locarno was signed by Germany, France, Belgium, Britain and Italy; it recognised Germany's borders with France and Belgium. Moreover, Britain, Italy and Belgium undertook to assist France in the case that German troops marched into the demilitarised Rheinland. Locarno paved the way for Germany's admission to the League of Nations in 1926.[27]

Hitler came to power in January 1933, and inaugurated an aggressive power designed to give Germany economic and political domination across central Europe. He did not attempt to recover the lost colonies. Until August 1939, the Nazis denounced Communists and the Soviet Union as the greatest enemy, along with the Jews.

Hitler's diplomatic strategy in the 1930s was to make seemingly reasonable demands, threatening war if they were not met. When opponents tried to appease him, he accepted the gains that were offered, then went to the next target. That aggressive strategy worked as Germany pulled out of the League of Nations (1933), rejected the Versailles Treaty and began to re-arm (1935), won back the Saar (1935), remilitarized the Rhineland (1936), formed an alliance ("axis") with Mussolini's Italy (1936), sent massive military aid to Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), seized Austria (1938), took over Czechoslovakia after the British and French appeasement of the Munich Agreement of 1938, formed a peace pact with Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union in August 1939, and finally invaded Poland in September 1939. Britain and France declared war and World War II began – somewhat sooner th

Fishnet Tights Porn

C Couple

Little Erotic Videos

College Fuck Sex

Porn Anal Bisexual

News - GERMAN-FOREIGN-POLICY.com

News - GERMAN-FOREIGN-POLICY.com

History of German foreign policy - Wikipedia

German Foreign Policy, 1933–1945 | Holocaust Encyclopedia

Foreign relations of Germany - Wikipedia

Germany - Foreign policy, 1890–1914 | Britannica

"Ambition in Security Policy" - GERMAN-FOREIGN-POLICY.com

Post-Merkel Germany May Be Shaded Green - The New York Times

German Foreign Policy