German Deutsch

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Not to be confused with Germanic languages.

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: The article's scope is unclear, article is contradicting. E.g.:

Infobox: Language family: High German -- Infobox: ISO 639-3: nds – Low German, Article: Dialects and Low German.

Low German is not a High German variety.

Grammar section covers Standard High German, which has its separate article: Standard German. (February 2021)

The German language (Deutsch, pronounced [dɔʏtʃ] (listen))[nb 4] is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is also a co-official language of Luxembourg, Belgium and parts of southwestern Poland, as well as a national language in Namibia. German is most similar to other languages within the West Germanic language branch, including Afrikaans, Dutch, English, the Frisian languages, Low German (Low Saxon), Luxembourgish, Scots, and Yiddish. It also contains close similarities in vocabulary to Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish, although these belong to the North Germanic group. German is the second most widely spoken Germanic language after English.

95 million (2014)[1]

L2 speakers: 10–15 million (2014)[1]

No official regulation

(Orthography regulated by the Council for German Orthography)[2]

high1289 High German

fran1268 Middle German

high1286 Upper German

52-ACB–dl (Standard German)

52-AC (Continental West Germanic)

52-ACB (Deutsch & Dutch)

52-ACB-d (Central German)

52-ACB-e & -f (Upper and Swiss German)

52-ACB-h (émigré German varieties, including 52-ACB-hc (Hutterite German) & 52-ACB-he (Pennsylvania German etc.)

52-ACB-i (Yenish)

Totalling 285 varieties: 52-ACB-daa to 52-ACB-i

(Co-)Official and majority language

Co-official, but not majority language

Statutory minority/cultural language

This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA.

One of the major languages of the world, German is a native language to almost 100 million people worldwide and is spoken by a total of over 130 million people.[5] It is the most spoken native language within the European Union.[1] German is also widely taught as a foreign language, especially in Europe, where it is the third most taught foreign language after English and French, and the United States. The language has been influential in the fields of philosophy, theology, science and technology. It is the second most commonly used scientific language and among the most widely used languages on websites. The German-speaking countries are ranked fifth in terms of annual publication of new books, with one tenth of all books (including e-books) in the world being published in German.

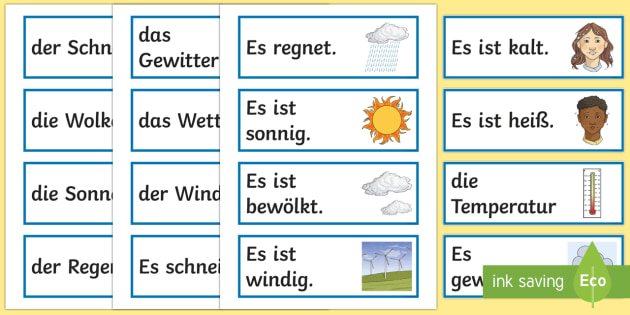

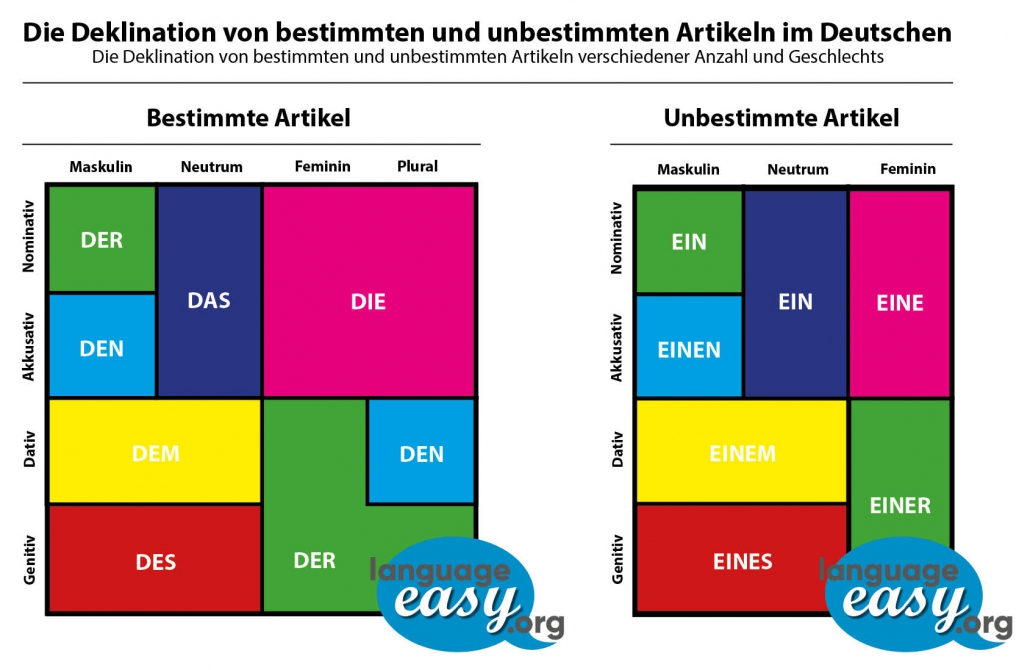

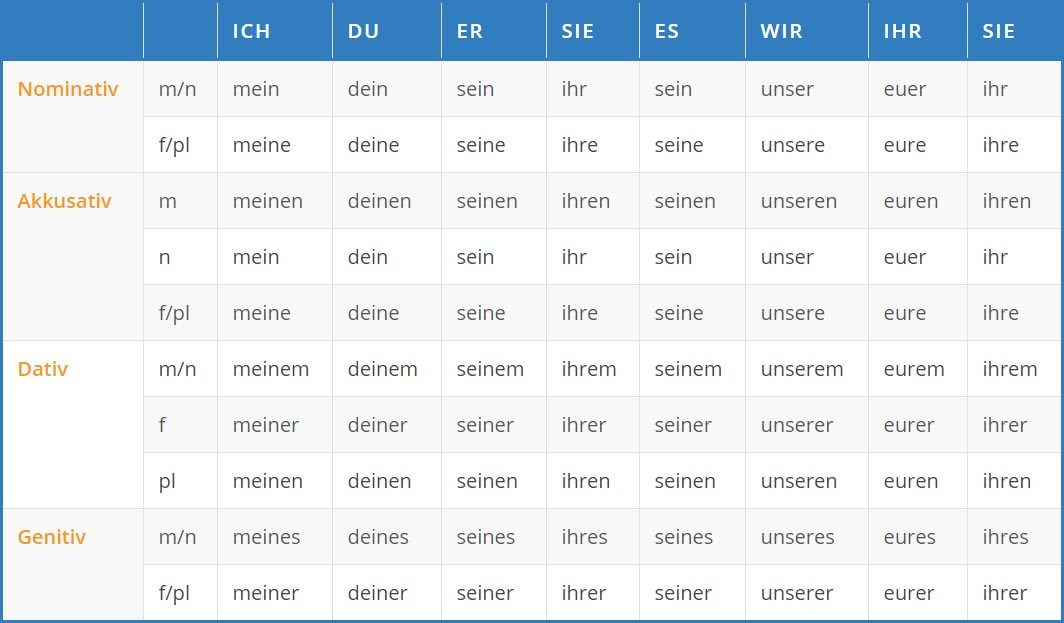

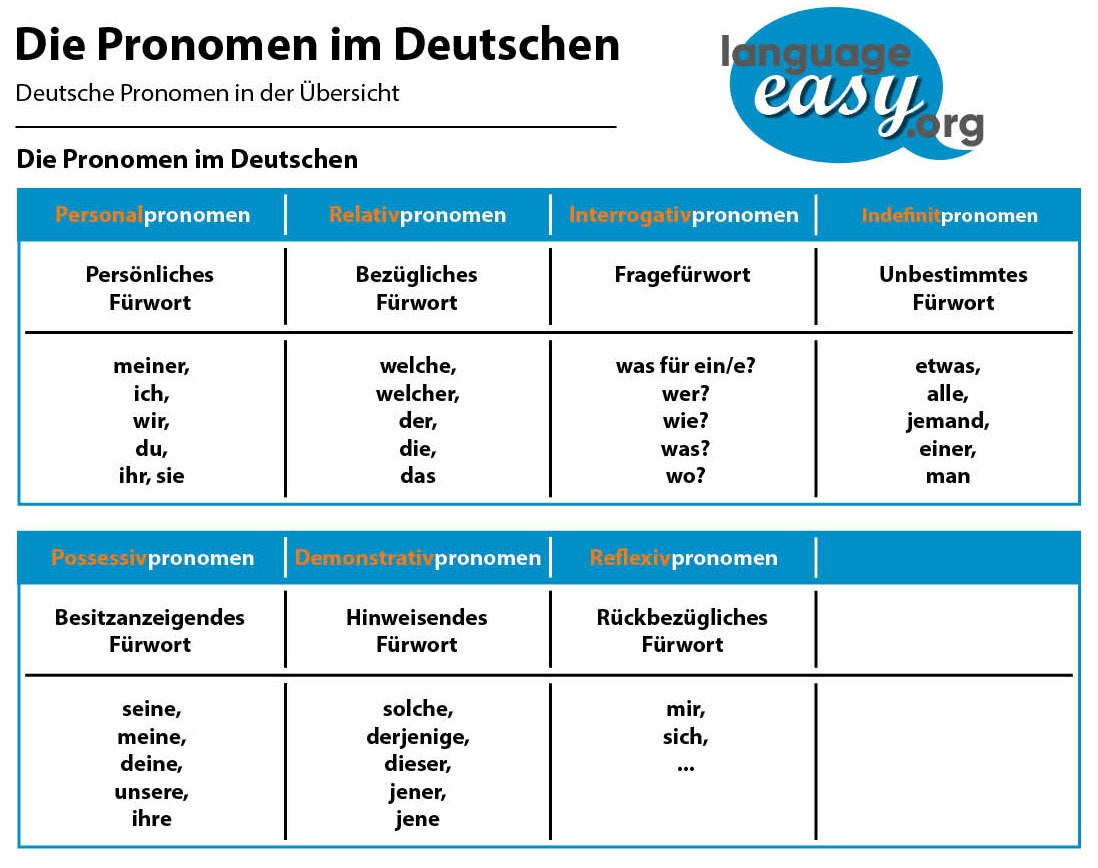

German is an inflected language, with four cases for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative); three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter); and two numbers (singular, plural). It has strong and weak verbs. The majority of its vocabulary derives from the ancient Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family, while a smaller share is partly derived from Latin and Greek, along with fewer words borrowed from French and Modern English.

As a pluricentric language, the standardized variants of German are German, Austrian, and Swiss Standard High German. It is also notable for its broad spectrum of dialects, with many varieties existing in Europe and other parts of the world. Some of these non-standard varieties have become recognized and protected by regional or national governments. Due to the limited intelligibility between certain varieties and Standard High German, as well as the lack of an undisputed, scientific distinction between a "dialect" and a "language", some German varieties or dialect groups such as Bavarian and Low German have been variously described as either "dialects" or separate languages.[6]

Modern Standard German is a West Germanic language in the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages. The Germanic languages are traditionally subdivided into three branches, North Germanic, East Germanic, and West Germanic. The first of these branches survives in modern Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Faroese, and Icelandic, all of which are descended from Old Norse. The East Germanic languages are now extinct, and Gothic is the only language in this branch which survives in written texts. The West Germanic languages, however, have undergone extensive dialectal subdivision and are now represented in modern languages such as English, German, Dutch, Yiddish, Afrikaans, and others.[7]

Within the West Germanic language dialect continuum, the Benrath and Uerdingen lines (running through Düsseldorf-Benrath and Krefeld-Uerdingen, respectively) serve to distinguish the Germanic dialects that were affected by the High German consonant shift (south of Benrath) from those that were not (north of Uerdingen). The various regional dialects spoken south of these lines are grouped as High German dialects, while those spoken to the north comprise the Low German/Low Saxon and Low Franconian dialects. As members of the West Germanic language family, High German, Low German, and Low Franconian have been proposed to be further distinguished historically as Irminonic, Ingvaeonic, and Istvaeonic, respectively. This classification indicates their historical descent from dialects spoken by the Irminones (also known as the Elbe group), Ingvaeones (or North Sea Germanic group), and Istvaeones (or Weser-Rhine group).[7]

Standard German is based on a combination of Thuringian-Upper Saxon and Upper Franconian dialects, which are Central German and Upper German dialects belonging to the High German dialect group. German is therefore closely related to the other languages based on High German dialects, such as Luxembourgish (based on Central Franconian dialects) and Yiddish. Also closely related to Standard German are the Upper German dialects spoken in the southern German-speaking countries, such as Swiss German (Alemannic dialects) and the various Germanic dialects spoken in the French region of Grand Est, such as Alsatian (mainly Alemannic, but also Central- and Upper Franconian dialects) and Lorraine Franconian (Central Franconian).

After these High German dialects, standard German is less closely related to languages based on Low Franconian dialects (e.g. Dutch and Afrikaans), Low German or Low Saxon dialects (spoken in northern Germany and southern Denmark), neither of which underwent the High German consonant shift. As has been noted, the former of these dialect types is Istvaeonic and the latter Ingvaeonic, whereas the High German dialects are all Irminonic; the differences between these languages and standard German are therefore considerable. Also related to German are the Frisian languages—North Frisian (spoken in Nordfriesland), Saterland Frisian (spoken in Saterland), and West Frisian (spoken in Friesland)—as well as the Anglic languages of English and Scots. These Anglo-Frisian dialects did not take part in the High German consonant shift.

The history of the German language begins with the High German consonant shift during the migration period, which separated Old High German dialects from Old Saxon. This sound shift involved a drastic change in the pronunciation of both voiced and voiceless stop consonants (b, d, g, and p, t, k, respectively). The primary effects of the shift were the following below.

While there is written evidence of the Old High German language in several Elder Futhark inscriptions from as early as the sixth century AD (such as the Pforzen buckle), the Old High German period is generally seen as beginning with the Abrogans (written c. 765–775), a Latin-German glossary supplying over 3,000 Old High German words with their Latin equivalents. After the Abrogans, the first coherent works written in Old High German appear in the ninth century, chief among them being the Muspilli, the Merseburg Charms, and the Hildebrandslied, and other religious texts (the Georgslied, the Ludwigslied, the Evangelienbuch, and translated hymns and prayers).[8][9] The Muspilli is a Christian poem written in a Bavarian dialect offering an account of the soul after the Last Judgment, and the Merseburg Charms are transcriptions of spells and charms from the pagan Germanic tradition. Of particular interest to scholars, however, has been the Hildebrandslied, a secular epic poem telling the tale of an estranged father and son unknowingly meeting each other in battle. Linguistically this text is highly interesting due to the mixed use of Old Saxon and Old High German dialects in its composition. The written works of this period stem mainly from the Alamanni, Bavarian, and Thuringian groups, all belonging to the Elbe Germanic group (Irminones), which had settled in what is now southern-central Germany and Austria between the second and sixth centuries during the great migration.[8]

In general, the surviving texts of OHG show a wide range of dialectal diversity with very little written uniformity. The early written tradition of OHG survived mostly through monasteries and scriptoria as local translations of Latin originals; as a result, the surviving texts are written in highly disparate regional dialects and exhibit significant Latin influence, particularly in vocabulary.[8] At this point monasteries, where most written works were produced, were dominated by Latin, and German saw only occasional use in official and ecclesiastical writing.

The German language through the OHG period was still predominantly a spoken language, with a wide range of dialects and a much more extensive oral tradition than a written one. Having just emerged from the High German consonant shift, OHG was also a relatively new and volatile language still undergoing a number of phonetic, phonological, morphological, and syntactic changes. The scarcity of written work, instability of the language, and widespread illiteracy of the time explain the lack of standardization up to the end of the OHG period in 1050.

While there is no complete agreement over the dates of the Middle High German (MHG) period, it is generally seen as lasting from 1050 to 1350.[10] This was a period of significant expansion of the geographical territory occupied by Germanic tribes, and consequently of the number of German speakers. Whereas during the Old High German period the Germanic tribes extended only as far east as the Elbe and Saale rivers, the MHG period saw a number of these tribes expanding beyond this eastern boundary into Slavic territory (known as the Ostsiedlung). With the increasing wealth and geographic spread of the Germanic groups came greater use of German in the courts of nobles as the standard language of official proceedings and literature.[10] A clear example of this is the mittelhochdeutsche Dichtersprache employed in the Hohenstaufen court in Swabia as a standardized supra-dialectal written language. While these efforts were still regionally bound, German began to be used in place of Latin for certain official purposes, leading to a greater need for regularity in written conventions.

While the major changes of the MHG period were socio-cultural, German was still undergoing significant linguistic changes in syntax, phonetics, and morphology as well (e.g. diphthongization of certain vowel sounds: hus (OHG "house")→haus (MHG), and weakening of unstressed short vowels to schwa [ə]: taga (OHG "days")→tage (MHG)).[11]

A great wealth of texts survives from the MHG period. Significantly, these texts include a number of impressive secular works, such as the Nibelungenlied, an epic poem telling the story of the dragon-slayer Siegfried (c. thirteenth century), and the Iwein, an Arthurian verse poem by Hartmann von Aue (c. 1203), lyric poems, and courtly romances such as Parzival and Tristan. Also noteworthy is the Sachsenspiegel, the first book of laws written in Middle Low German (c. 1220). The abundance and especially the secular character of the literature of the MHG period demonstrate the beginnings of a standardized written form of German, as well as the desire of poets and authors to be understood by individuals on supra-dialectal terms.

The Middle High German period is generally seen as ending when the 1346–53 Black Death decimated Europe's population.[12]

Modern German begins with the Early New High German (ENHG) period, which the influential German philologist Wilhelm Scherer dates 1350–1650, terminating with the end of the Thirty Years' War.[12] This period saw the further displacement of Latin by German as the primary language of courtly proceedings and, increasingly, of literature in the German states. While these states were still under the control of the Holy Roman Empire, and far from any form of unification, the desire for a cohesive written language that would be understandable across the many German-speaking principalities and kingdoms was stronger than ever. As a spoken language German remained highly fractured throughout this period, with a vast number of often mutually incomprehensible regional dialects being spoken throughout the German states; the invention of the printing press c. 1440 and the publication of Luther's vernacular translation of the Bible in 1534, however, had an immense effect on standardizing German as a supra-dialectal written language.

The ENHG period saw the rise of several important cross-regional forms of chancery German, one being gemeine tiutsch, used in the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, and the other being Meißner Deutsch, used in the Electorate of Saxony in the Duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg.[13]

Alongside these courtly written standards, the invention of the printing press led to the development of a number of printers' languages (Druckersprachen) aimed at making printed material readable and understandable across as many diverse dialects of German as possible.[14] The greater ease of production and increased availability of written texts brought about increased standardization in the written form of German.

One of the central events in the development of ENHG was the publication of Luther's translation of the Bible into German (the New Testament was published in 1522; the Old Testament was published in parts and completed in 1534). Luther based his translation primarily on the Meißner Deutsch of Saxony, spending much time among the population of Saxony researching the dialect so as to make the work as natural and accessible to German speakers as possible. Copies of Luther's Bible featured a long list of glosses for each region, translating words which were unknown in the region into the regional dialect. Luther said the following concerning his translation method:

One who would talk German does not ask the Latin how he shall do it; he must ask the mother in the home, the children on the streets, the common man in the market-place and note carefully how they talk, then translate accordingly. They will then understand what is said to them because it is German. When Christ says 'ex abundantia cordis os loquitur,' I would translate, if I followed the papists, aus dem Überflusz des Herzens redet der Mund. But tell me is this talking German? What German understands such stuff? No, the mother in the home and the plain man would say, Wesz das Herz voll ist, des gehet der Mund über.[15]

With Luther's rendering of the Bible in the vernacular, German asserted itself against the dominance of Latin as a legitimate language for courtly, literary, and now ecclesiastical subject-matter. Furthermore, his Bible was ubiquitous in the German states: nearly every household possessed a copy.[16] Nevertheless, even with the influence of Luther's Bible as an unofficial written standard, a widely accepted standard for written German did not appear until the middle of the eighteenth century.[17]

German was the language of commerce and government in the Habsburg Empire, which encompassed a large area of Central and Eastern Europe. Until the mid-nineteenth century, it was essentially the language of townspeople throughout most of the Empire. Its use indicated that the speaker was a merchant or someone from an urban area, regardless of nationality.

Prague (German: Prag) and Budapest (Buda, German: Ofen), to name two examples, were gradually Germanized in the years after their incorporation into the Habsburg domain, others like Pozsony (German: Pressburg, now Bratislava), were originally settled during the Habsburg period and were primarily German at that time. Prague, Budapest, Bratislava, and cities like Zagreb (German: Agram) or Ljubljana (German: Laibach), contained significant German minorities.

In the eastern provinces of Banat, Bukovina, and Transylvania (German: Banat, Buchenland, Siebenbürgen), German was the predominant language not only in the larger towns – like Temeschburg (Timișoara), Hermannstadt (Sibiu) and Kronstadt (Brașov) – but also in many smaller localities in the surrounding areas.[18]

The most comprehensive guide to the vocabulary of the German language is found within the Deutsches Wörterbuch. This dictionary was created by the Brothers Grimm, and is composed of 16 parts which were issued between 1852 and 1860. In 1872, grammatical and orthographic rules first appeared in the Duden Handbook.[19]

In 1901, the 2nd Orthographical Conference ended with a complete standardisation of the German language in its written form, and the Duden Handbook was declared its standard definition.[20] The Deutsche Bühnensprache (lit. 'German stage language') had established conventions for German pronunciation in theatres[21] three years earlier; however, this was an artificial standard that did not correspond to any traditional spoken dialect. Rather, it was based on the pronunciation of Standard German in Northern Germany, although it was subsequently regarded often as a general prescriptive norm, despite differing pronunciation traditions especially in the Upper-German-speaking regions that still characterise the dialect of the area today – especially the pronunciation of the ending -ig as [ɪk] instead of [ɪç]. In Northern Germany, Standard German was a foreign language to most inhabitants, whose native dialects were subsets of Low German. It was usually encountered only in writing or formal speech; in fact, most of Standard German was a written language, not identical to any spoken dialect, throughout the German-speaking area until well into the 19th century.

Official revisions of some of the rules from 1901 were not issued until the controversial German orthography reform of 1996 was made the official standard by governments of all German-speaking countries.[22] Media and wr

Students Fuck Video

Couple First Sex

Mature Nl Fucking Hd Sex

Dick Out

Destroy Dick

german-deutsch.com - Learn German for free - Deutsch ...

German language - Wikipedia

Немецкий язык - Germany.ru

Free German Online Courses Level A1 to B1 | DW Learn Germ…

Google Translate

A multilingual website to learn German - deutsch.info

German Keyboard - Deutsch Keyboard - Type German Online

German Deutsch

.svg/1024px-Flag_of_Germany_(state).svg.png)