Fornix Vaginae

🛑 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Fornix Vaginae

ADVERTISEMENT: Radiopaedia is free thanks to our supporters and advertisers. Become a Gold Supporter and see no ads.

Must contain: at least 8 characters 1 uppercase letter, 1 lowercase letter, 1 number

Josiah To et al.,

JAMA Ophthalmology, 2019

J. W. Bullard,

Journal of American Medical Association

GEO. ERETY SHOEMAKER,

Journal of American Medical Association

HENRY T. BYFORD,

Journal of American Medical Association

Stephanie Sarny et al.,

JAMA Ophthalmology, 2018

Precision Oncology News, 2020

Targeting settings

Do not sell my personal information

Google Analytics settings

I consent to the use of Google Analytics and related cookies across the TrendMD network (widget, website, blog). Learn more

Synonyms or Alternate Spellings: Fornix vaginae

This site is for use by medical professionals . To continue you must accept our use of cookies and the site's Terms of Use .

Enter your email and create a password for your account

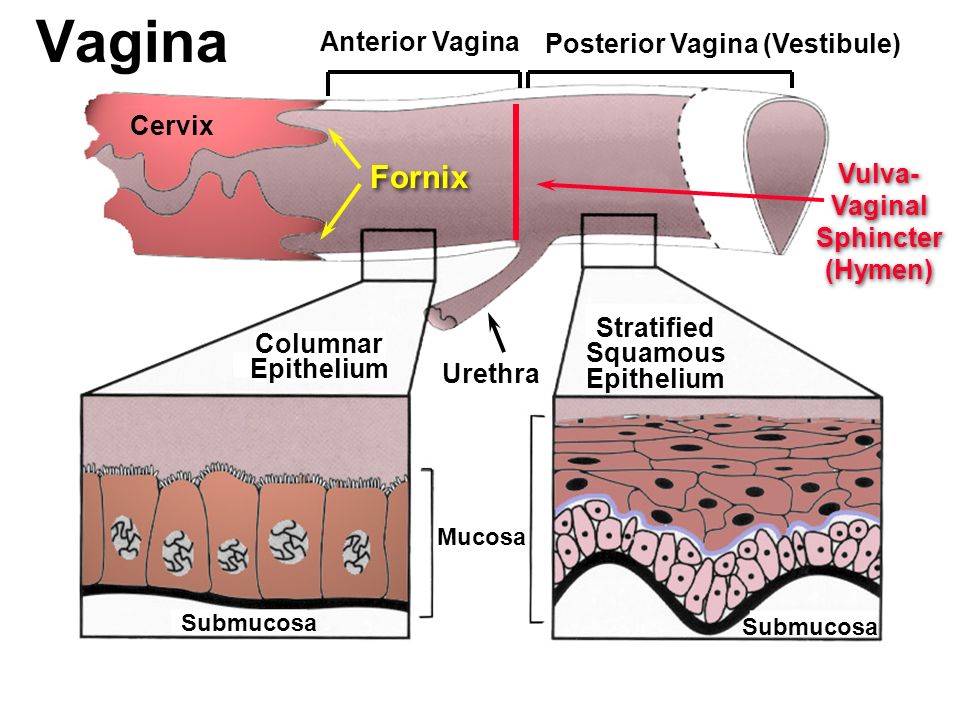

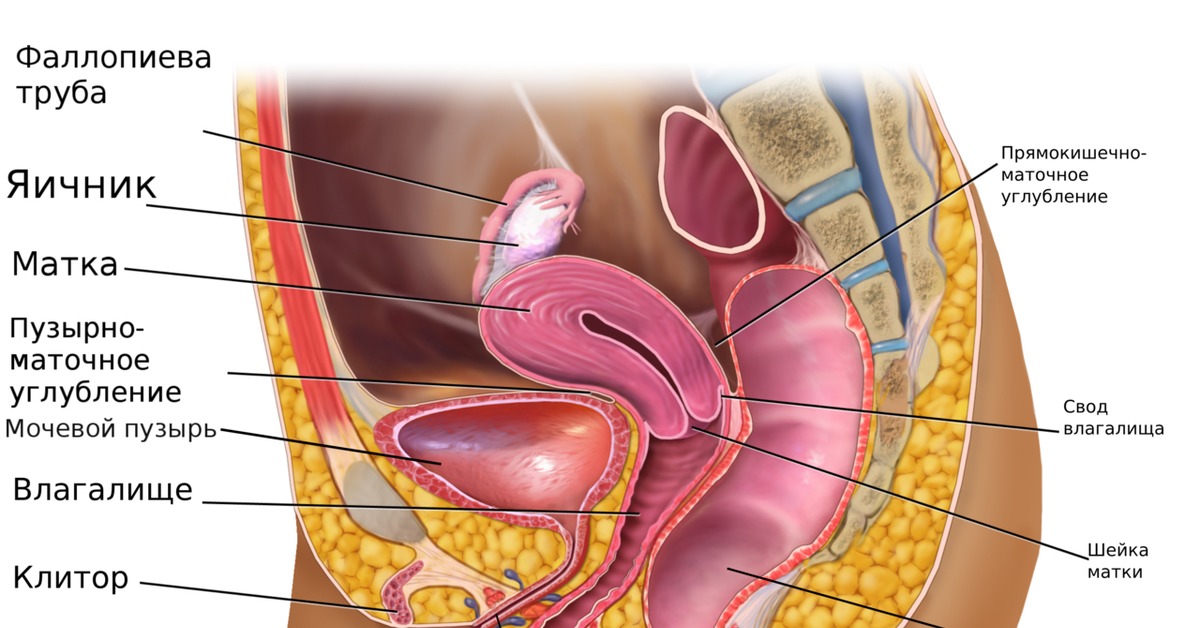

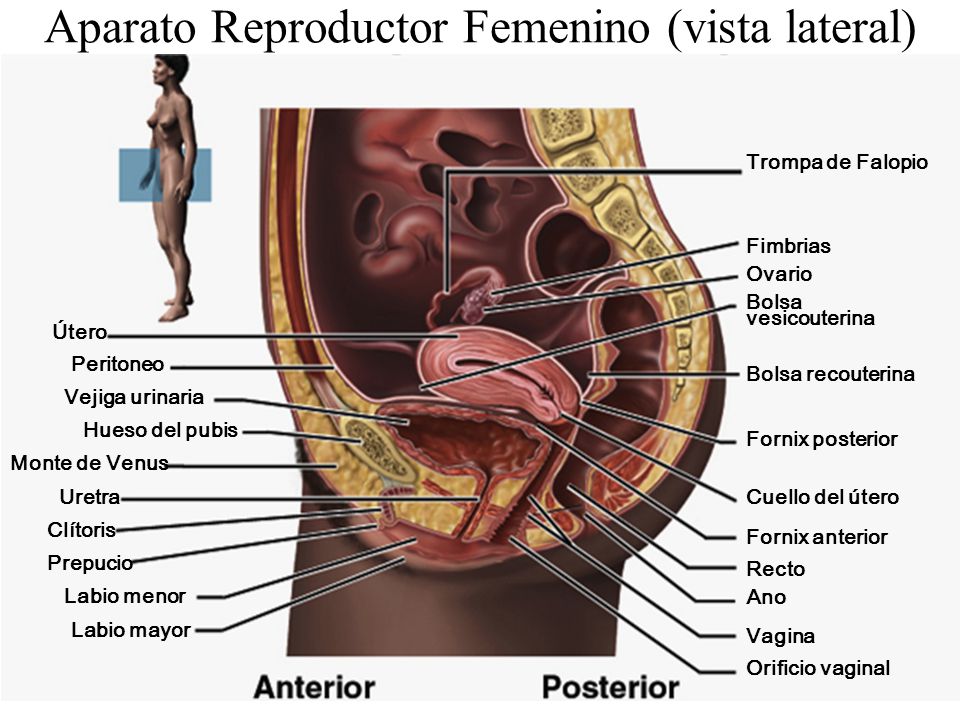

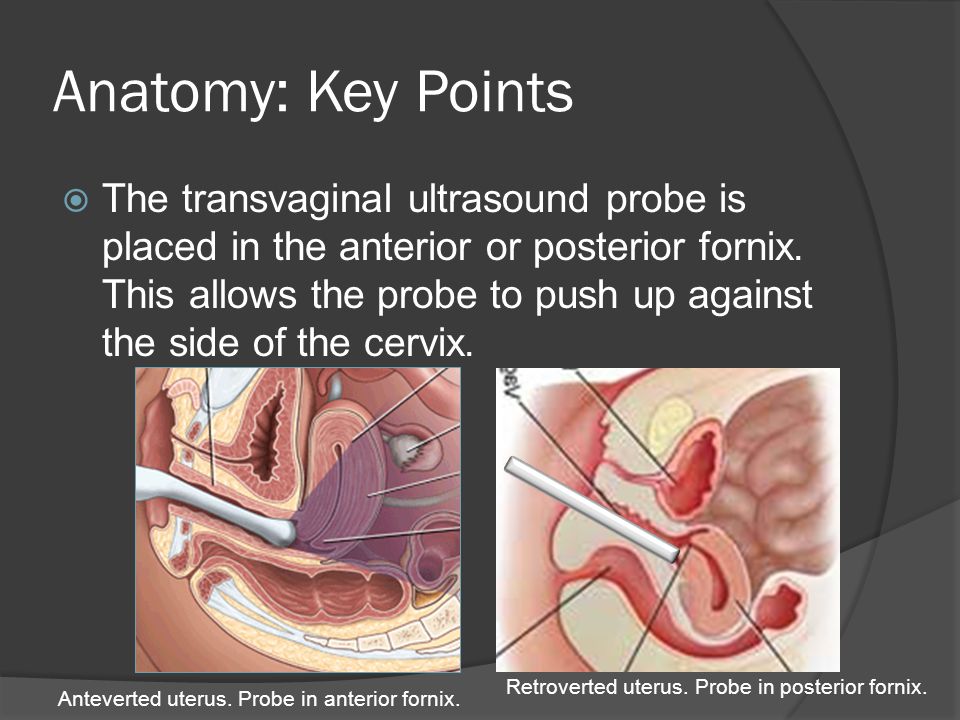

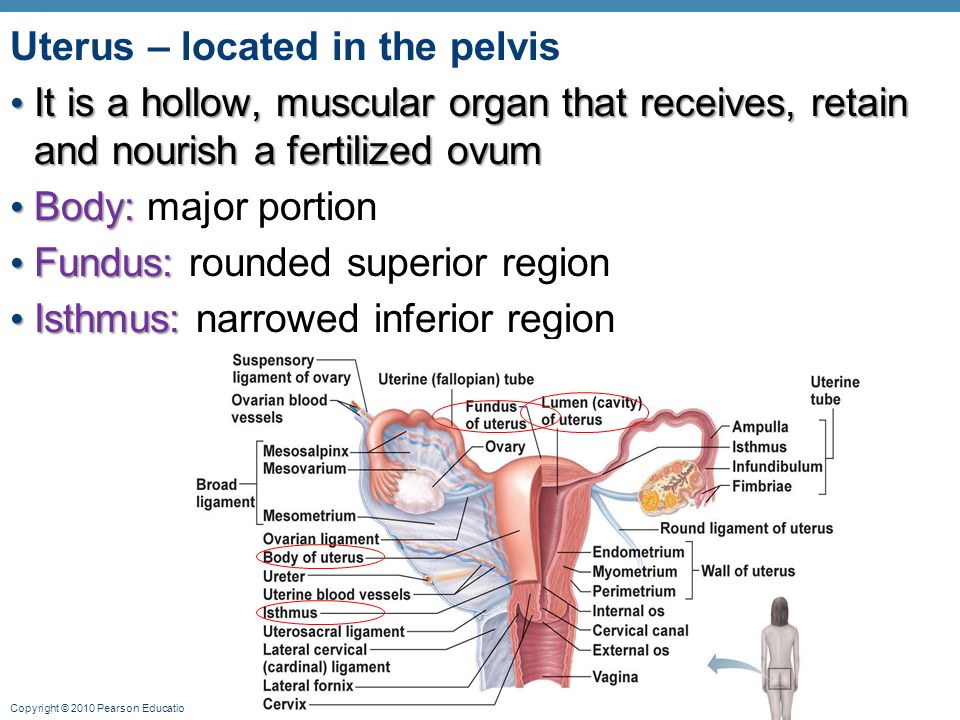

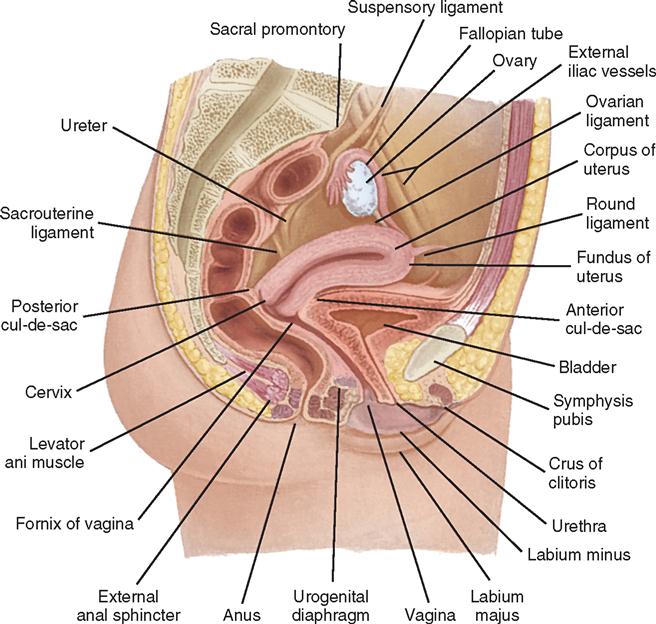

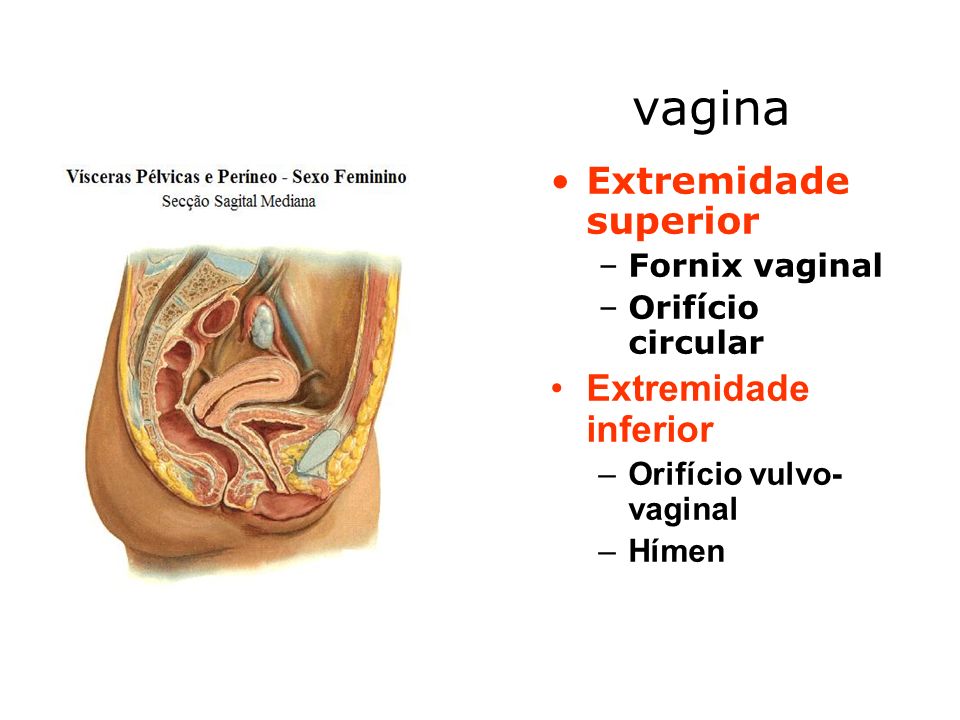

The fornices are superior recesses of the vagina formed by the protrusion of the cervix into the vaginal vault. There is a large posterior fornix and a smaller anterior fornix with two small lateral fornices.

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

Please Note: You can also scroll through stacks with your mouse wheel or the keyboard arrow keys

Unable to process the form. Check for errors and try again.

Thank you for updating your details.

fornix vaginae — с итальянского на русский

Fornix ( vagina ) | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org

Vaginal Fornix - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

Vaginal fornix - Wikiwand

Definition of Vaginal fornix

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9781455708925000246

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9781416099796007406

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780721693231500313

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012812972250009X

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780723436607000122

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780721602523500266

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780721693231500106

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9781437708677000363

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444536327009266

Breeding lacerations are typically located in the vaginal fornix dorsal and lateral to the cervix.

Vaginal varicosities are generally located at the vestibulovaginal ring (on the cranial vestibular fold and the dorsal, caudal vaginal wall).

Endoscopy may be required to see vaginal varicosities given their cranial and dorsal location; visualize the cervix and then retroflex the endoscope 180 degrees to view the cranial aspect of the vestibulovaginal ring.

Endoscopy may be helpful in identifying the source of postpartum hemorrhage.

Digital examination helps determine whether vaginal perforation has occurred following natural breeding.

Recommended in cases of vaginal perforation

Septic peritonitis (see p. 219 ), or rarely, seminoperitoneum can occur

Seminoperitoneum refers to sperm in the peritoneal cavity; the reaction to the foreign protein (sperm) typically creates a nonseptic peritonitis; the sperm are found free in the peritoneal fluid or phagocytosed within leukocytes.

Vaginal laceration without perforation:

Begin oral broad-spectrum antimicrobials, trimethoprim/sulfa, 30 mg/kg PO q12h.

Ensure mare is current on tetanus toxoid prophylaxis.

Do not rebreed the mare by natural cover during the current estrous cycle.

Use a “breeding roll” to avoid vaginal laceration/perforation.

Breeding rolls are recommended for:

Vaginal laceration with perforation:

These lacerations are rarely amenable to repair; therefore, allow to heal by second intention.

Begin broad-spectrum antimicrobials: potassium penicillin, 22,000 IU/kg IV q6h; or procaine penicillin, 22,000 IU/kg IM q12h with gentamicin, 6.6 mg/kg IV/IM q24h.

Start intravenous fluids if the clinical picture indicates their use is warranted.

Give flunixin meglumine (0.5 to 1 mg/kg IV/PO q12h) if the mare is straining or febrile.

If intestine has herniated through the vaginal perforation, rinse bowel with sterile saline and replace in the abdomen.

Place a Caslick's suture to prevent aspiration of air into the abdominal cavity.

If peritonitis is severe or bowel has entered the vagina, transfer to a referral center as quickly as possible for surgery and/or peritoneal lavage; if surgery is not an option or the peritonitis is not severe, the mare should be cross-tied for several days to reduce the risk of intestinal evisceration.

Mares should not be rebred until the following breeding season.

Often, no treatment is needed because the vessels regress and the bleeding stops once the mare foals.

If the bleeding is excessive or constant or the owners are concerned, the vessels can be ligated, cauterized, surgically resected, or hemorrhoid cream can be applied topically; transendoscopic laser photocoagulation is another option for the treatment of vaginal varicosities.

Most vaginal hemorrhage following foaling is not life threatening and seldom requires treatment.

Profuse bleeding requires that the vessels be identified and ligated, if possible.

If the source of bleeding cannot be identified, then the vaginal cavity can be packed with a large tampon made of rolled cotton, stockinette, and umbilical tape; cover the tampon with petroleum jelly and oily antibiotics, and leave in place for 24 to 48 hours.

Minor vaginal lacerations heal by second intention.

Significant lacerations should be sutured if possible.

Mares with deep lacerations should be given broad-spectrum antimicrobials (trimethoprim/sulfa, 30 mg/kg PO q12h) and lavaged with dilute povidone-iodine solution (2%) to prevent abscess formation.

Mares with significant vaginal trauma may form vaginal adhesions; daily application of a topical antimicrobial ointment containing steroid (Animax 5 ) may help prevent adhesion formation.

Large vaginal hematomas may form, making it difficult and painful for the mare to defecate; feed mares a laxative diet until the hematoma diminishes in size. Administer broad-spectrum antimicrobials (trimethoprim sulfa, 30 mg/kg PO q12h), NSAIDs (phenylbutazone, 2.2 mg/kg PO q12h or flunixin meglumine, 0.5 to 1.1 mg/kg PO/IV q12h) to alleviate pain, and tetanus toxoid prophylaxis.

Urine dripping from the vulva during exercise or at rest

Urine scalding on the caudal medial thighs

History of infertility or reduced fertility

Vaginal speculum examination shows a pool of urine in the ventral aspect of the vaginal fornix and a cranioventral slope of the vaginal vault with inflammation of the cranial vagina and cervix.

In normal young mares, the reproductive tract slopes craniodorsally, and the vestibule and vagina are mostly contained within the pelvic cavity. The vagina may slope cranioventrally and fall below the level of the pelvic floor because of increased age. After multiple pregnancies, stretching and relaxation of the reproductive tract occurring during vaginal delivery may also lead to urine pooling. This often worsens with each foaling. Because of these physical changes, urine may collect in the cranial vagina, where it provides a spermicidal environment and irritates the vaginal mucosa, predisposing to vaginitis, cervicitis, and endometritis. Affected mares often have some degree of abnormal perineal conformation such as a sunken anus or dorsally sloped vulva. Poor perineal conformation may be caused by loss of pelvic fat.

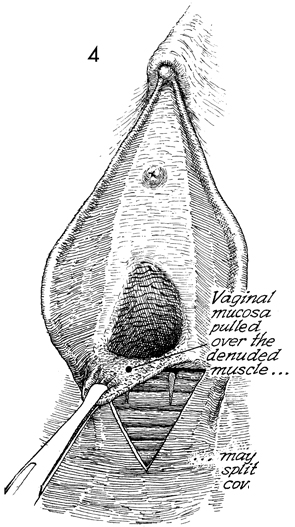

The vaginal lips are spread, which allows the vagina to dilate with air and facilitates the vaginal incision. Incision of the vaginal fornix is usually made at the 2 o'clock position, 2 to 4 cm dorsolateral to the cervix. This position is preferable to the 10 o'clock location because it provides more direct access to the right ovary, which is located further cranially. The incision is made with a No. 15 Bard-Parker blade (Becton-Dickinson, Rutherford, NJ) protected by the thumb and fingers, limiting forward thrust. Only the vaginal mucosa should be incised in order to minimize trauma to the iliac artery and the rectum. Penetration of the abdomen is done with blunt dissecting scissors; the opening is then manually enlarged. Excessive pain is prevented by slowly stretching the peritoneal opening. After the ovary is located, ovarian ligament analgesia is performed as previously described. An écraseur (see Fig. 28-10 ) is introduced into the abdomen with the chain slightly slack, allowing one finger through the loop. The ovary is identified and the chain looped around the base of the ovary. Edges of the chain should be carefully examined for trapped intestine or mesentery after initial tightening but before crushing and cutting of tissue. An assistant then gradually tightens the chain while the surgeon holds the ovary. To prevent excessive pain and provide for optimal crushing, the chain is tightened one click every 10 to 15 seconds until the stump is transected. The instrument and the ovary are then removed. During the procedure it is important to keep the instrument as far cranial as possible, preventing tension on the ovarian ligament.

A. Carretero , ... M. Navarro , in Morphological Mouse Phenotyping , 2017

The vagina is the female copulatory organ. In the mouse, it extends from the cervix to the vulva , with the cranial portion of the vagina, surrounding the cervix, forming a broad vaginal fornix ( Fig. 9-13 ). The wall of the vagina has a tunica mucosa, consisting of a stratified squamous epithelium with numerous folds and a lamina propria of fibrous nature ( Figs. 9-14 and 9-15 ). The tunica muscularis of vagina is very thin and externally is covered by a tunica serosa. The vaginal epithelium undergoes marked changes in response to hormone state ( Fig. 9-15 ). The epithelium, in proestrus, is very thick and is incompletely keratinized. During estrus, the epithelium appears completely keratinized and their superficial cells begin to the detach into the vaginal cavity. In metaestrus, the desquamation of epithelial cells occurs and leukocyte infiltration of the epithelium begins. In diestrus, the epithelium is very thin and characterized by more prominent infiltration by leukocytes, while mucus appears in the vaginal cavity.

Figure 9-13 . Structure of the cervix of uterus. A) Horizontal histological section of uterus. B and B ′) Transverse histological sections of the prevaginal portion of cervix of uterus. Hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichrome stains, respectively (20X). C and C ′) Transverse histological sections of the vaginal portion of cervix of uterus. Hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichrome stains, respectively (20X).

1: Right horn of uterus; 2: Left horn of uterus; 3: Uterine velum; 4: Cervix of uterus; 5: Prevaginal portion; 6: Vaginal portion; 7: External orifice of uterus; 8: Vaginal fornix; 9: Cervical canal.

Figure 9-14 . Vagina and female urethra. A , B , C and D) Histological sections. Hematoxylin-eosin stain (B: 20X; C: 200X and D: 400X). B ′) Histological section. Masson’s trichrome stain (20X). E) Magnetic resonance image. Transverse section. F) Ultrasound image.

1: Vagina; 2: Lumen of vagina; 3: Tunica mucosa; 4: Lamina propria; 5: Tunica muscularis; 6: Tunica serosa; 7: Lumen of urethra; 8: Transitional epithelium of urethra; 9: Corpus spongiosum; 10: Urethral glands; 11: Sinus of preputial gland; 12: Rectum; 13: Pelvic limb.

Figure 9-15 . Structure of vagina. Histological sections. Hematoxylin-eosin stain (400X). A) Scanning electron microscopy image of the vaginal mucosa (Bar = 0.25 mm). B) Proestrus. C) Estrus. D) Metaestrus. E) Diestrus.

1: Vaginal portion (cervix of uterus); 2: External orifice of uterus; 3: Vaginal fornix; 4: Lumen of vagina; 5: Tunica mucosa; 6: Stratified squamous epithelium; 7: Lamina propria; 8: Stratum corneum; 9: Stratum spinosum; 10: Stratum basale; 11: Mucus; 12: Vaginal folds.

Mares may show varying signs ranging from none, to urine staining or crystals below her vulva extending down between her legs or urine squirting through her vulva when the mare moves or runs.

Diagnosis can be made by identifying urine at the vaginal fornix during speculum examination. The condition may be intermittent with mares being more likely to pool urine during estrus than diestrus due to increased relaxation of the reproductive tract under the influence of estrogen.

Hyperemia of the vaginal vault may be present without evidence of urine and culture of the endometrium can be negative if bacterial contamination from the vaginal vault has not occurred. Endometrial cytology, with or without the presence of bacteria, reveals inflammatory cells and frequently urine crystals.

Ultrasonographic examination can be used to detect fluid in the cranial vagina and in the uterine body. Endometrial biopsy is recommended before treatment is initiated to ascertain the chronicity and severity of the disease by the fibrotic and inflammatory changes. This will provide the owner with a realistic idea of whether or not the mare will be able to carry a foal to term if she does become pregnant.

Cervical lacerations or damage and associated adhesions can occur in a spontaneous and otherwise uneventful parturition. Stage II of parturition can be described as explosive in the mare with most normal foals passing through the birth canal in less than 20 minutes. If cervical softening is inadequate due to maiden status or anxiety, the cervix may not have sufficient time to fully relax before fetal expulsion. Cervical adhesions are frequently present with cervical lacerations and seem to develop as the laceration heals. Abraded or lacerated cervical mucosa tends to heal rapidly and adheres to any mucosal surface that it contacts. Adhesions present with cervical lacerations most often form from flaps of portio vaginalis tissue that adhere to the vaginal fornix . These adhesions are clinically significant because they prevent the caudal aspect of the cervix from closing and forming a competent canal of sufficient length. More extensive and severe cervical adhesions may develop after a dystocia. The mare's pelvic canal seems to be prone to pressure necrosis caused by the fetus being wedged in the cervix and pelvic canal. This results in tissue ischemia and subsequent sloughing of cervical and vaginal mucosa. The raw tissue that is exposed is at risk for developing transluminal adhesions. Mares undergoing fetotomy have the potential for even more extensive pressure necrosis and additional lacerations inflicted by the obstetric wire and equipment. Subsequent metritis exacerbates the mucosal inflammation and prolongs the healing time, often resulting in an irregular, firm, and inelastic cervix.

Although administration of some uterine therapy using caustic irritants is thought to stimulate and improve the endometrium, the cervix and vagina seem to be less tolerant of irritants. The cervix and vagina are more likely to become severely inflamed and form extensive transluminal adhesions between mucosal surfaces in the lumen of the cervix. The serosal surface of the cervix may adhere to the vaginal fornix, resulting in pericervical adhesions. Forced manual delivery of a greater-than-60-day conceptus during elective pregnancy termination that was initiated by repeated prostag-landin administration frequently results in circumferential tight rings of fibrotic tissue that constrict the cervical lumen. 2

TIMOTHY J. EVANS , ... VENKATASESHU K. GANJAM , in Current Therapy in Large Animal Theriogenology (Second Edition) , 2007

For purposes of this discussion, the vagina of the mare represents the caudalmost derivative of the paramesonephric ducts and is sometimes called the vagina proper (see Figs. 7-2 and 7-5 ). The vestibule will be discussed separately later in this chapter. Located in the pelvic cavity, the vagina is approximately 20 to 25 cm in length and extends from the recess surrounding the terminal segment of the uterine cervix ( vaginal fornix ) to the prominent transverse fold overlying the external urethral orifice, which is a remnant of the hymen. Only the cranial portions of the vagina are covered by peritoneum. The extent of this coverage is determined by the variations in size of the rectogenital and vesicogenital pouches dorsally and ventrally, respectively. Collagenous connective tissue, fasciae, and muscles surround the portion of the vagina that is not covered by peritoneum. 1, 4, 6, 7, 10, 11 Like the myometrium, the muscular layer of the vagina comprises a thinner longitudinal layer of smooth muscle and an inner, thicker layer of circular smooth muscle. The lamina propria of the vagina is well vascularized but is aglandular. Stratified squamous epithelium, consisting of basal, middle, and superficial regions, covers the vaginal mucosa, which is arranged in longitudinal folds. 1, 4

David E. Freeman , in Equine Surgery (Fourth Edition) , 2012

Small intestine can become strangulated in mesenteric ligamentous bands that cannot be exteriorized at surgery and must be cut blindly with scissors. Small intestine can also become strangulated by uterine torsion; through rents in the mesometrium, gastrohepatic ligament, small colon mesentery, lateral ligament of the urinary bladder, cecocolic fold, and mesentery of the large colon; by components of the spermatic cord, particularly the mesoductus deferens; and by omental adhesions. 129-131,133,221,319-323 Evisceration through a lacerated vaginal fornix , a defect in the bladder and urethra, or a castration wound may cause small intestinal strangulating obstruction. 284,324 Entrapment of small intestine within the nephrosplenic space has been reported in two horses, with the bowel passing from craniad to caudad. 325 Both horses were presented alert and in stable condition, and the affected segments of bowel did not require resection. 325 Mesenteric hematomas of unknown origin can cause colic and ischemic necrosis of affected intestine. 326 Surgical access to the source of hemorrhage may be difficult. 326

Adhesions after small intestinal surgery or any intra-abdominal procedure can form an axis around which attached small intestine can form a volvulus, or adhesions can form fibrous bands through which small intestinal loops can become strangulated. 224,327 Nonstrangulating infarction and necrotizing enterocolitis in the small intestine are rare and have a poor prognosis. 125,328

B. Thomadsen , R. Miller , in Comprehensive Biomedical Physics , 2014

The intent of Point A was to provide an anatomical proxy. Point A represents the location where the uterine vessels cross the ureter. The definition of Point A has been revised and modified several times. In the original classic Manchester system definition, Point A was defined as 2 cm superior to the top of the vaginal fornix and 2 cm lateral to the middle of the tandem based on the construction of the Manchester applicator ( Tod and Meredith, 1938 ). This point was later modified to correspond to a point 2 cm superior to the bottom of the inferior tandem source (equivalent to the external cervical os for their applicator) and 2 cm lateral to the middle of the tandem to allow radiographic localization for individual patients ( Potish, 1990; Tod and Meredith, 1953 ). Many clinical practices transferred this procedure to other applicators and also moved the starting point along the tandem to the flange that abutted the external cervical os. The dose points were determined from orthogonal radiographs; Point A was placed 2 cm superior to the flange of the intrauterine tandem, which could be identified radiographically and 2 cm lateral from the central uterine canal ( ICRU International Commission on Radiological Units Measurements, 1985 ). The problem with this application of the revised definition was that it moved Point A from a low-gradient position along the tandem to a high-gradient position near the ovoids, resulting in unstable dosimetry ( Potish, 1990; Potish et al., 1995 ). The ABS presented another definition of Point A, suggesting it be named Point H to avoid confusion with prior definitions, based the ovoids that would place Point A in the original position ( Nag et al., 2000b ). Determining the location used the following procedure:

Connect the center of the two ovoids with a straight line and locate the intersection with the tandem.

Move along the tandem the radius of the ovoids and continue 2 cm more along the tandem.

Point H falls 2 cm lateral to this position on the tandem.

For a tandem and ring applicator, the first step is slightly different: begin by drawing the line between the lateral-most positions in the ring and locate the intersection with the tandem. The rest of the procedure is the same.

Point B was a surrogate for the dose to the obdurator lymph nodes. Point B has been defined as 5 cm lateral to patient’s midline at the level of Point A ( ICRU, 1985; Tod and Meredith, 1938 ). Lee et al. demonstrated that Point B was a poor proxy for lymphatic nodes and suggested that CT imaging should be used if an accurate dose to the lymphatic nodal chain was warranted ( Lee et al., 2009 ). The ABS discourages the use of Point B entirely ( Nag et al., 2000c ).

We use cookies to help provide and enhance our service and tailor content and ads. By continuing you agree to the use of cookies .

Copyright © 2021 Elsevier B.V. or its licensors or contributors. ScienceDirect ® is a registered trademark of Elsevier B.V.

ScienceDirect ® is a registered trademark of Elsevier B.V.

+Ostium+vaginae.+Vestibulum+vaginae.+Paries+anterior.+Paries+posterior.+Rugae+vaginales..jpg)

%20urinary%20bladder.jpg" width="550" alt="Fornix Vaginae" title="Fornix Vaginae">

%20urinary%20bladder.jpg" width="550" alt="Fornix Vaginae" title="Fornix Vaginae">