Female Genital Mutilation

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Select language

Select language

English

العربية

中文

Français

Русский

Español

COVID-19 continues to disrupt essential health services in 90% of countries

Statement of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization: Continued review of emerging evidence on AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccines

Key facts

Female genital mutilation (FGM) involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

The practice has no health benefits for girls and women.

FGM can cause severe bleeding and problems urinating, and later cysts, infections, as well as complications in childbirth and increased risk of newborn deaths.

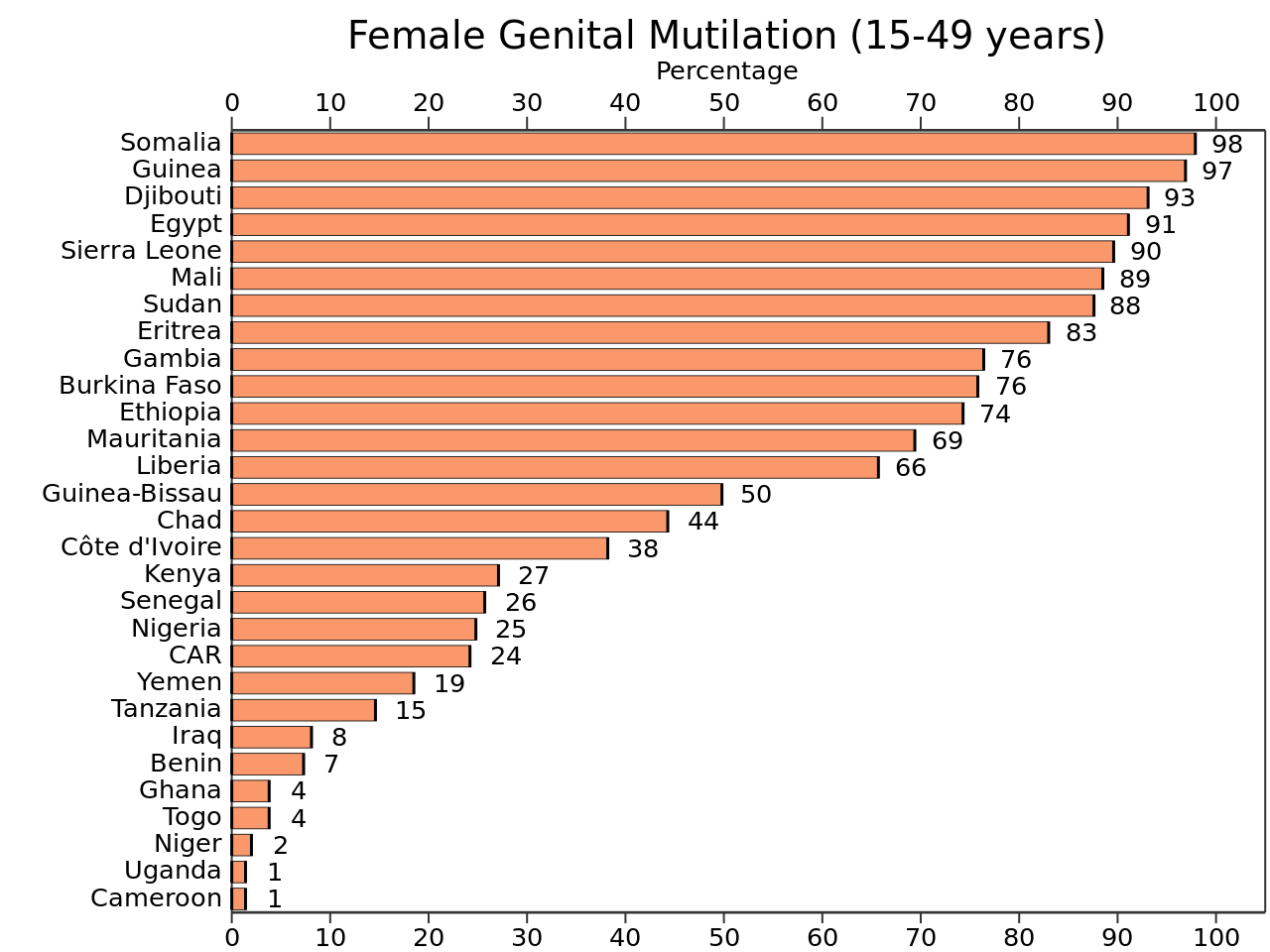

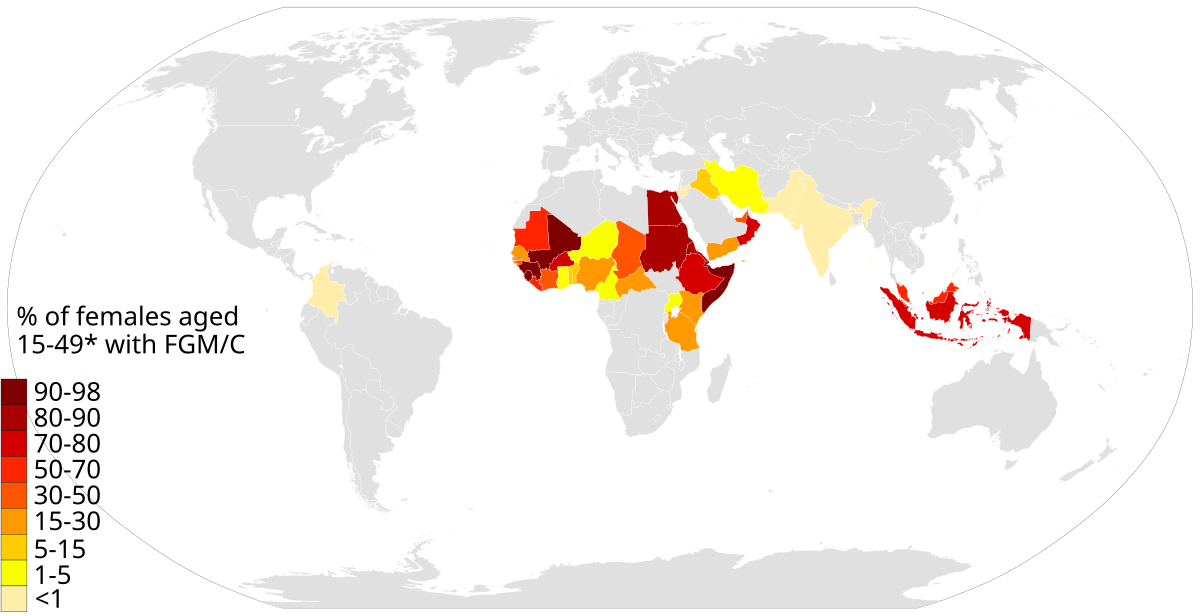

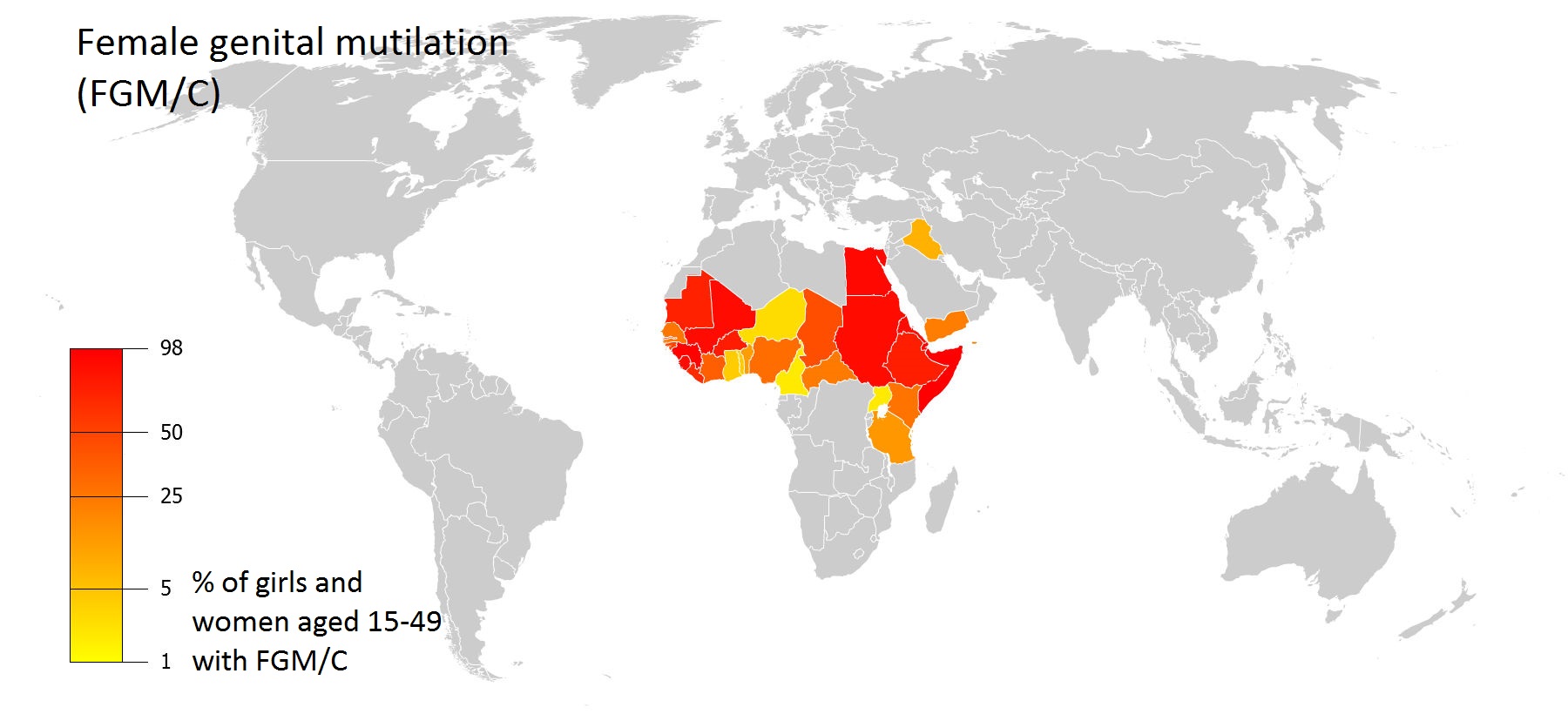

More than 200 million girls and women alive today have been cut in 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia where FGM is concentrated (1).

FGM is mostly carried out on young girls between infancy and age 15.

FGM is a violation of the human rights of girls and women.

WHO is opposed to all forms of FGM, and is opposed to health care providers performing FGM (medicalization of FGM).

Treatment of health complications of FGM in 27 high prevalence countries costs 1.4 billion USD per year.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) comprises all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

The practice is mostly carried out by traditional circumcisers, who often play other central roles in communities, such as attending childbirths. In many settings, health care providers perform FGM due to the belief that the procedure is safer when medicalized1. WHO strongly urges health care providers not to perform FGM.

FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women. It is nearly always carried out on minors and is a violation of the rights of children. The practice also violates a person's rights to health, security and physical integrity, the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and the right to life when the procedure results in death.

Female genital mutilation is classified into 4 major types.

Deinfibulation refers to the practice of cutting open the sealed vaginal opening of a woman who has been infibulated, which is often necessary for improving health and well-being as well as to allow intercourse or to facilitate childbirth.

FGM has no health benefits, and it harms girls and women in many ways. It involves removing and damaging healthy and normal female genital tissue, and interferes with the natural functions of girls' and women's bodies. Generally speaking, risks of FGM increase with increasing severity (which here corresponds to the amount of tissue damaged), although all forms of FGM are associated with increased health risk.

Immediate complications can include:

Long-term complications can include:

FGM is mostly carried out on young girls sometime between infancy and adolescence, and occasionally on adult women. More than 3 million girls are estimated to be at risk for FGM annually.

More than 200 million girls and women alive today have been subjected to the practice , according to data from 30 countries where population data exist. 1.

The practice is mainly concentrated in the Western, Eastern, and North-Eastern regions of Africa, in some countries the Middle East and Asia, as well as among migrants from these areas. FGM is therefore a global concern.

The reasons why female genital mutilations are performed vary from one region to another as well as over time, and include a mix of sociocultural factors within families and communities. The most commonly cited reasons are:

WHO has conducted a study of the economic costs of treating health complications of FGM and has found that the current costs for 27 countries where data were available totalled 1.4 billion USD during a one year period (2018). This amount is expected to rise to 2.3 billion in 30 years (2047) if FGM prevalence remains the same – corresponding to a 68% increase in the costs of inaction. However, if countries abandon FGM, these costs would decrease by 60% over the next 30 years.

Building on work from previous decades, in 1997, WHO issued a joint statement against the practice of FGM together with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Since 1997, great efforts have been made to counteract FGM, through research, work within communities, and changes in public policy. Progress at international, national and sub-national levels includes:

Research shows that, if practicing communities themselves decide to abandon FGM, the practice can be eliminated very rapidly.

In 2007, UNFPA and UNICEF initiated the Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting to accelerate the abandonment of the practice.

In 2008, WHO together with 9 other United Nations partners, issued a statement on the elimination of FGM to support increased advocacy for its abandonment, called: “Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement”. This statement provided evidence collected over the previous decade about the practice of FGM.

In 2010, WHO published a "Global strategy to stop health care providers from performing female genital mutilation" in collaboration with other key UN agencies and international organizations. WHO supports countries to implement this strategy.

In December 2012, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution on the elimination of female genital mutilation.

Building on a previous report from 2013, in 2016 UNICEF launched an updated report documenting the prevalence of FGM in 30 countries, as well as beliefs, attitudes, trends, and programmatic and policy responses to the practice globally.

In May 2016, WHO in collaboration with the UNFPA-UNICEF joint programme on FGM launched the first evidence-based guidelines on the management of health complications from FGM. The guidelines were developed based on a systematic review of the best available evidence on health interventions for women living with FGM.

In 2018, WHO launched a clinical handbook on FGM to improve knowledge, attitudes, and skills of health care providers in preventing and managing the complications of FGM.

In 2008, the World Health Assembly passed resolution WHA61.16 on the elimination of FGM, emphasizing the need for concerted action in all sectors - health, education, finance, justice and women's affairs.

WHO efforts to eliminate female genital mutilation focus on:

The economic cost of female genital mutilation 6 February 2020

Unleashing Youth Power:A Decade of Accelerating Actions Towards Zero Female Genital Mutilation 6 February 2020

Female Genital Mutilation Hurts Women and Economies 6 February 2020

Working towards zero tolerance for female genital mutilation in Sudan 6 February 2018

In Somalia, health workers, girls and women are experts in preventing female genital mutilation 4 February 2021

A hybrid, effectiveness-implementation research study for female genital mutilation prevention and care in Guinea, Kenya and Somalia

"FGM" redirects here. For other uses, see FGM (disambiguation).

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision,[a] is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. The practice is found in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and within communities from countries in which FGM is common. UNICEF estimated in 2016 that 200 million women living today in 30 countries—27 African countries, Indonesia, Iraqi Kurdistan and Yemen—have undergone the procedures.[3]

Road sign near Kapchorwa, Uganda, 2004

"Partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons" (WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA, 1997).[1]

Africa, Southeast Asia, Middle East, and within communities from these areas[2]

Over 200 million women and girls in 27 African countries; Indonesia; Iraqi Kurdistan; and Yemen (as of 2016)[3]

Typically carried out by a traditional circumciser using a blade, FGM is conducted from days after birth to puberty and beyond. In half of the countries for which national figures are available, most girls are cut before the age of five.[6] Procedures differ according to the country or ethnic group. They include removal of the clitoral hood and clitoral glans; removal of the inner labia; and removal of the inner and outer labia and closure of the vulva. In this last procedure, known as infibulation, a small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid; the vagina is opened for intercourse and opened further for childbirth.[7]

The practice is rooted in gender inequality, attempts to control women's sexuality, and ideas about purity, modesty and beauty. It is usually initiated and carried out by women, who see it as a source of honour, and who fear that failing to have their daughters and granddaughters cut will expose the girls to social exclusion.[8] Adverse health effects depend on the type of procedure; they can include recurrent infections, difficulty urinating and passing menstrual flow, chronic pain, the development of cysts, an inability to get pregnant, complications during childbirth, and fatal bleeding.[7] There are no known health benefits.[9]

There have been international efforts since the 1970s to persuade practitioners to abandon FGM, and it has been outlawed or restricted in most of the countries in which it occurs, although the laws are often poorly enforced. Since 2010, the United Nations has called upon healthcare providers to stop performing all forms of the procedure, including reinfibulation after childbirth and symbolic "nicking" of the clitoral hood.[10] The opposition to the practice is not without its critics, particularly among anthropologists, who have raised difficult questions about cultural relativism and the universality of human rights.[11]

Until the 1980s FGM was widely known in English as female circumcision, implying an equivalence in severity with male circumcision.[5] From 1929 the Kenya Missionary Council referred to it as the sexual mutilation of women, following the lead of Marion Scott Stevenson, a Church of Scotland missionary.[12] References to the practice as mutilation increased throughout the 1970s.[13] In 1975 Rose Oldfield Hayes, an American anthropologist, used the term female genital mutilation in the title of a paper in American Ethnologist,[14] and four years later Fran Hosken called it mutilation in her influential The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females.[15] The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children began referring to it as female genital mutilation in 1990, and the World Health Organization (WHO) followed suit in 1991.[16] Other English terms include female genital cutting (FGC) and female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), preferred by those who work with practitioners.[13]

In countries where FGM is common, the practice's many variants are reflected in dozens of terms, often alluding to purification.[17] In the Bambara language, spoken mostly in Mali, it is known as bolokoli ("washing your hands")[18] and in the Igbo language in eastern Nigeria as isa aru or iwu aru ("having your bath").[b] A common Arabic term for purification has the root t-h-r, used for male and female circumcision (tahur and tahara).[20] It is also known in Arabic as khafḍ or khifaḍ.[21] Communities may refer to FGM as "pharaonic" for infibulation and "sunna" circumcision for everything else;[22] sunna means "path or way" in Arabic and refers to the tradition of Muhammad, although none of the procedures are required within Islam.[21] The term infibulation derives from fibula, Latin for clasp; the Ancient Romans reportedly fastened clasps through the foreskins or labia of slaves to prevent sexual intercourse. The surgical infibulation of women came to be known as pharaonic circumcision in Sudan and as Sudanese circumcision in Egypt.[23] In Somalia, it is known simply as qodob ("to sew up").[24]

The procedures are generally performed by a traditional circumciser (cutter or exciseuse) in the girls' homes, with or without anaesthesia. The cutter is usually an older woman, but in communities where the male barber has assumed the role of health worker he will also perform FGM.[25][c] When traditional cutters are involved, non-sterile devices are likely to be used, including knives, razors, scissors, glass, sharpened rocks and fingernails.[27] According to a nurse in Uganda, quoted in 2007 in The Lancet, a cutter would use one knife on up to 30 girls at a time.[28] In several countries, health professionals are involved; in Egypt 77 percent of FGM procedures, and in Indonesia over 50 percent, were performed by medical professionals as of 2008 and 2016.[29][3]

The WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA issued a joint statement in 1997 defining FGM as "all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons".[13] The procedures vary according to ethnicity and individual practitioners; during a 1998 survey in Niger, women responded with over 50 terms when asked what was done to them.[17] Translation problems are compounded by the women's confusion over which type of FGM they experienced, or even whether they experienced it.[30] Studies have suggested that survey responses are unreliable. A 2003 study in Ghana found that in 1995 four percent said they had not undergone FGM, but in 2000 said they had, while 11 percent switched in the other direction.[31] In Tanzania in 2005, 66 percent reported FGM, but a medical exam found that 73 percent had undergone it.[32] In Sudan in 2006, a significant percentage of infibulated women and girls reported a less severe type.[33]

Standard questionnaires from United Nations bodies ask women whether they or their daughters have undergone the following: (1) cut, no flesh removed (symbolic nicking); (2) cut, some flesh removed; (3) sewn closed; or (4) type not determined/unsure/doesn't know.[d] The most common procedures fall within the "cut, some flesh removed" category and involve complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans.[34] The World Health Organization (a UN agency) created a more detailed typology in 1997: Types I–II vary in how much tissue is removed; Type III is equivalent to the UNICEF category "sewn closed"; and Type IV describes miscellaneous procedures, including symbolic nicking.[35]

Type I is "partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce". Type Ia[e] involves removal of the clitoral hood only. This is rarely performed alone.[f] The more common procedure is Type Ib (clitoridectomy), the complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans (the visible tip of the clitoris) and clitoral hood.[1][38] The circumciser pulls the clitoral glans with her thumb and index finger and cuts it off.[g]

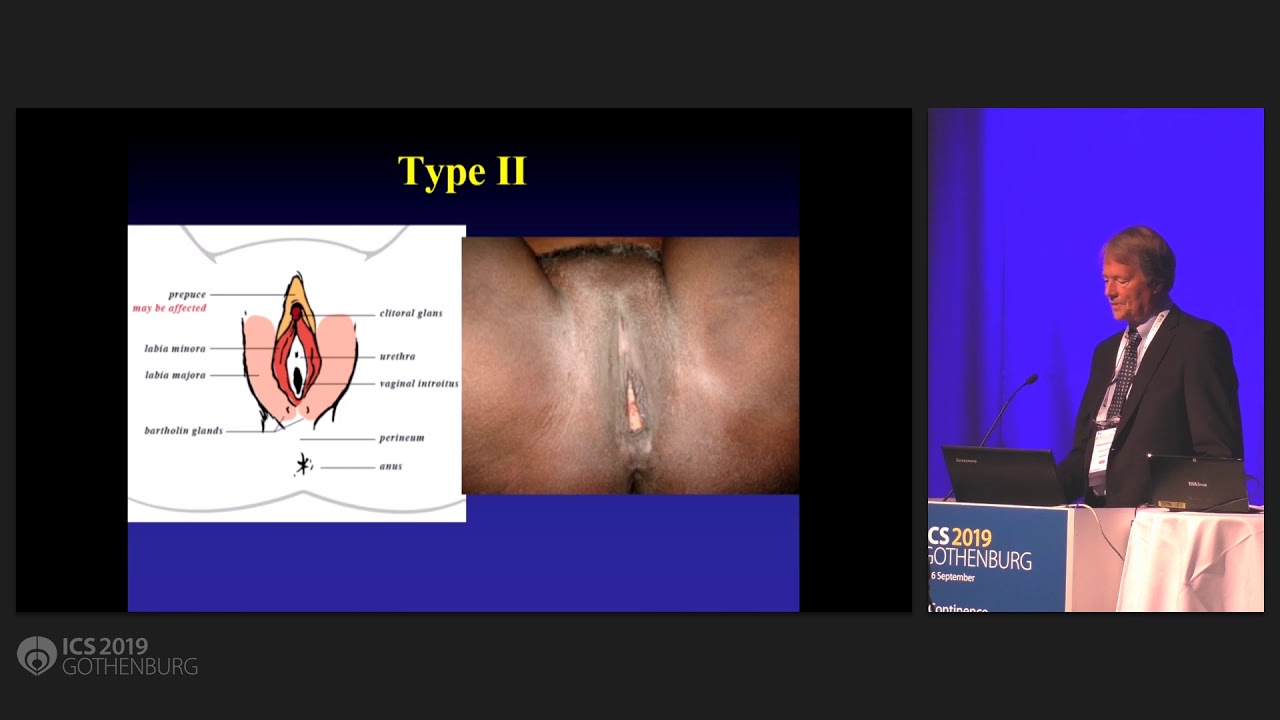

Type II (excision) is the complete or partial removal of the inner labia, with or without removal of the clitoral glans and outer labia. Type IIa is removal of the inner labia; Type IIb, removal of the clitoral glans and inner labia; and Type IIc, removal of the clitoral glans, inner and outer labia. Excision in French can refer to any form of FGM.[1]

Type III (infibulation or pharaonic circumcision), the "sewn closed" category, is the removal of the external genitalia and fusion of the wound. The inner and/or outer labia are cut away, with or without removal of the clitoral glans.[h] Type III is found largely in northeast Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan (although not in South Sudan). According to one 2008 estimate, over eight million women in Africa are living with Type III FGM.[i] According to UNFPA in 2010, 20 percent of women with FGM have been infibulated.[41] In Somalia, according to Edna Adan Ismail, the child squats on a stool or mat while adults pull her legs open; a local anaesthetic is applied if available:

The element of speed and surprise is vital and the circumciser immediately grabs the clitoris by pinching it between her nails aiming to amputate it with a slash. The organ is then shown to the senior female relatives of the child who will decide whether the amount that has been removed is satisfactory or whether more is to be cut off.

After the clitoris has been satisfactorily amputated ... the circumciser can proceed with the total removal of the labia minora and the paring of the inner walls of the labia majora. Since the entire skin on the inner walls of the labia majora has to be removed all the way down to the perineum, this becomes a messy business. By now, the child is screaming, struggling, and bleeding profusely, which makes it difficult for the circumciser to hold with bare fingers and nails the slippery skin and parts that are to be cut or sutured together. ...

Having ensured that sufficient tissue has been removed to allow the desired fusion of the skin, the circumciser pulls together the opposite sides of the labia majora, ensuring that the raw edges where the skin has been removed are well approximated. The wound is now ready to be stitched or for thorns to be applied. If a needle and thread are being used, close tight sutures will be placed to ensure that a flap of skin covers the vulva and extends from the mons veneris to the perineum, and which, after the wound heals, will form a bridge of scar tissue that will totally occlude the vaginal introitus.[42]

The amputated parts might be placed in a pouch for the girl to wear.[43] A single hole of 2–3 mm is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid.[j] The vulva is closed with surgical thread, or agave or acacia thorns, and might be covered with a poultice of raw egg, herbs and sugar. To help the tissue bond, the girl's legs are tied together, often from hip to ankle; the bindings are usually loosened after a week and removed after two to six weeks.[44][27] If the remaining hole is too large in the view of the girl's family, the procedure is repeated.[45]

The vagina is opened for sexual intercourse, for the first time either by a midwife with a knife or by the woman's husband with his penis.[46] In some areas, including Somaliland, female relatives of the bride and groom might watch the opening of the vagina to check that the girl is a virgin.[44] The woman is opened further for childbirth (defibulation or deinfibulation), and closed again afterwards (reinfibulation). Reinfibulation can involve cutting the vagina again to restore the pinhole size of the first infibulation. This might be performed before marriage, and after childbirth, divorce and widowhood.[k][47] Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed hundreds of w

Powerful Couple

Hot Pussy Ebony

Cute Teen Doggystyle

Lada Granta Desperate Fox 2021

Porno Mom Milf Son

Female genital mutilation - World Health Organization

Female genital mutilation - Wikipedia

WHO | Female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation | UNFPA - United Nations ...

Female genital mutilation (FGM) - NHS

Female Genital Mutilation FGM | Plan International

Female Genital Mutilation

%3abackground_color(FFFFFF)%3aformat(jpeg)/images/library/6130/Normal_Vagina.png)