Female Circumcision

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

"FGM" redirects here. For other uses, see FGM (disambiguation).

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision,[a] is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. The practice is found in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and within communities from countries in which FGM is common. UNICEF estimated in 2016 that 200 million women living today in 30 countries—27 African countries, Indonesia, Iraqi Kurdistan and Yemen—have undergone the procedures.[3]

Road sign near Kapchorwa, Uganda, 2004

"Partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons" (WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA, 1997).[1]

Africa, Southeast Asia, Middle East, and within communities from these areas[2]

Over 200 million women and girls in 27 African countries; Indonesia; Iraqi Kurdistan; and Yemen (as of 2016)[3]

Typically carried out by a traditional circumciser using a blade, FGM is conducted from days after birth to puberty and beyond. In half of the countries for which national figures are available, most girls are cut before the age of five.[6] Procedures differ according to the country or ethnic group. They include removal of the clitoral hood and clitoral glans; removal of the inner labia; and removal of the inner and outer labia and closure of the vulva. In this last procedure, known as infibulation, a small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid; the vagina is opened for intercourse and opened further for childbirth.[7]

The practice is rooted in gender inequality, attempts to control women's sexuality, and ideas about purity, modesty and beauty. It is usually initiated and carried out by women, who see it as a source of honour, and who fear that failing to have their daughters and granddaughters cut will expose the girls to social exclusion.[8] Adverse health effects depend on the type of procedure; they can include recurrent infections, difficulty urinating and passing menstrual flow, chronic pain, the development of cysts, an inability to get pregnant, complications during childbirth, and fatal bleeding.[7] There are no known health benefits.[9]

There have been international efforts since the 1970s to persuade practitioners to abandon FGM, and it has been outlawed or restricted in most of the countries in which it occurs, although the laws are often poorly enforced. Since 2010, the United Nations has called upon healthcare providers to stop performing all forms of the procedure, including reinfibulation after childbirth and symbolic "nicking" of the clitoral hood.[10] The opposition to the practice is not without its critics, particularly among anthropologists, who have raised difficult questions about cultural relativism and the universality of human rights.[11]

Until the 1980s FGM was widely known in English as female circumcision, implying an equivalence in severity with male circumcision.[5] From 1929 the Kenya Missionary Council referred to it as the sexual mutilation of women, following the lead of Marion Scott Stevenson, a Church of Scotland missionary.[12] References to the practice as mutilation increased throughout the 1970s.[13] In 1975 Rose Oldfield Hayes, an American anthropologist, used the term female genital mutilation in the title of a paper in American Ethnologist,[14] and four years later Fran Hosken called it mutilation in her influential The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females.[15] The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children began referring to it as female genital mutilation in 1990, and the World Health Organization (WHO) followed suit in 1991.[16] Other English terms include female genital cutting (FGC) and female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), preferred by those who work with practitioners.[13]

In countries where FGM is common, the practice's many variants are reflected in dozens of terms, often alluding to purification.[17] In the Bambara language, spoken mostly in Mali, it is known as bolokoli ("washing your hands")[18] and in the Igbo language in eastern Nigeria as isa aru or iwu aru ("having your bath").[b] A common Arabic term for purification has the root t-h-r, used for male and female circumcision (tahur and tahara).[20] It is also known in Arabic as khafḍ or khifaḍ.[21] Communities may refer to FGM as "pharaonic" for infibulation and "sunna" circumcision for everything else;[22] sunna means "path or way" in Arabic and refers to the tradition of Muhammad, although none of the procedures are required within Islam.[21] The term infibulation derives from fibula, Latin for clasp; the Ancient Romans reportedly fastened clasps through the foreskins or labia of slaves to prevent sexual intercourse. The surgical infibulation of women came to be known as pharaonic circumcision in Sudan and as Sudanese circumcision in Egypt.[23] In Somalia, it is known simply as qodob ("to sew up").[24]

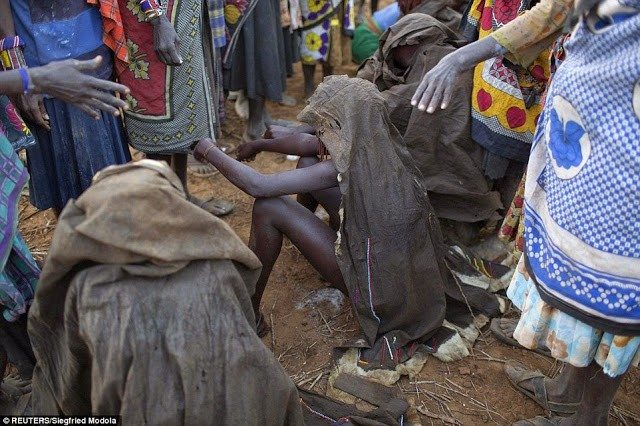

The procedures are generally performed by a traditional circumciser (cutter or exciseuse) in the girls' homes, with or without anaesthesia. The cutter is usually an older woman, but in communities where the male barber has assumed the role of health worker he will also perform FGM.[25][c] When traditional cutters are involved, non-sterile devices are likely to be used, including knives, razors, scissors, glass, sharpened rocks and fingernails.[27] According to a nurse in Uganda, quoted in 2007 in The Lancet, a cutter would use one knife on up to 30 girls at a time.[28] In several countries, health professionals are involved; in Egypt 77 percent of FGM procedures, and in Indonesia over 50 percent, were performed by medical professionals as of 2008 and 2016.[29][3]

The WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA issued a joint statement in 1997 defining FGM as "all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons".[13] The procedures vary according to ethnicity and individual practitioners; during a 1998 survey in Niger, women responded with over 50 terms when asked what was done to them.[17] Translation problems are compounded by the women's confusion over which type of FGM they experienced, or even whether they experienced it.[30] Studies have suggested that survey responses are unreliable. A 2003 study in Ghana found that in 1995 four percent said they had not undergone FGM, but in 2000 said they had, while 11 percent switched in the other direction.[31] In Tanzania in 2005, 66 percent reported FGM, but a medical exam found that 73 percent had undergone it.[32] In Sudan in 2006, a significant percentage of infibulated women and girls reported a less severe type.[33]

Standard questionnaires from United Nations bodies ask women whether they or their daughters have undergone the following: (1) cut, no flesh removed (symbolic nicking); (2) cut, some flesh removed; (3) sewn closed; or (4) type not determined/unsure/doesn't know.[d] The most common procedures fall within the "cut, some flesh removed" category and involve complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans.[34] The World Health Organization (a UN agency) created a more detailed typology in 1997: Types I–II vary in how much tissue is removed; Type III is equivalent to the UNICEF category "sewn closed"; and Type IV describes miscellaneous procedures, including symbolic nicking.[35]

Type I is "partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce". Type Ia[e] involves removal of the clitoral hood only. This is rarely performed alone.[f] The more common procedure is Type Ib (clitoridectomy), the complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans (the visible tip of the clitoris) and clitoral hood.[1][38] The circumciser pulls the clitoral glans with her thumb and index finger and cuts it off.[g]

Type II (excision) is the complete or partial removal of the inner labia, with or without removal of the clitoral glans and outer labia. Type IIa is removal of the inner labia; Type IIb, removal of the clitoral glans and inner labia; and Type IIc, removal of the clitoral glans, inner and outer labia. Excision in French can refer to any form of FGM.[1]

Type III (infibulation or pharaonic circumcision), the "sewn closed" category, is the removal of the external genitalia and fusion of the wound. The inner and/or outer labia are cut away, with or without removal of the clitoral glans.[h] Type III is found largely in northeast Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan (although not in South Sudan). According to one 2008 estimate, over eight million women in Africa are living with Type III FGM.[i] According to UNFPA in 2010, 20 percent of women with FGM have been infibulated.[41] In Somalia, according to Edna Adan Ismail, the child squats on a stool or mat while adults pull her legs open; a local anaesthetic is applied if available:

The element of speed and surprise is vital and the circumciser immediately grabs the clitoris by pinching it between her nails aiming to amputate it with a slash. The organ is then shown to the senior female relatives of the child who will decide whether the amount that has been removed is satisfactory or whether more is to be cut off.

After the clitoris has been satisfactorily amputated ... the circumciser can proceed with the total removal of the labia minora and the paring of the inner walls of the labia majora. Since the entire skin on the inner walls of the labia majora has to be removed all the way down to the perineum, this becomes a messy business. By now, the child is screaming, struggling, and bleeding profusely, which makes it difficult for the circumciser to hold with bare fingers and nails the slippery skin and parts that are to be cut or sutured together. ...

Having ensured that sufficient tissue has been removed to allow the desired fusion of the skin, the circumciser pulls together the opposite sides of the labia majora, ensuring that the raw edges where the skin has been removed are well approximated. The wound is now ready to be stitched or for thorns to be applied. If a needle and thread are being used, close tight sutures will be placed to ensure that a flap of skin covers the vulva and extends from the mons veneris to the perineum, and which, after the wound heals, will form a bridge of scar tissue that will totally occlude the vaginal introitus.[42]

The amputated parts might be placed in a pouch for the girl to wear.[43] A single hole of 2–3 mm is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid.[j] The vulva is closed with surgical thread, or agave or acacia thorns, and might be covered with a poultice of raw egg, herbs and sugar. To help the tissue bond, the girl's legs are tied together, often from hip to ankle; the bindings are usually loosened after a week and removed after two to six weeks.[44][27] If the remaining hole is too large in the view of the girl's family, the procedure is repeated.[45]

The vagina is opened for sexual intercourse, for the first time either by a midwife with a knife or by the woman's husband with his penis.[46] In some areas, including Somaliland, female relatives of the bride and groom might watch the opening of the vagina to check that the girl is a virgin.[44] The woman is opened further for childbirth (defibulation or deinfibulation), and closed again afterwards (reinfibulation). Reinfibulation can involve cutting the vagina again to restore the pinhole size of the first infibulation. This might be performed before marriage, and after childbirth, divorce and widowhood.[k][47] Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed hundreds of women and men in Sudan in the 1980s about sexual intercourse with Type III:

The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man's potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman's vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. ... Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the "little knife". This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis.[48]

Type IV is "[a]ll other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes", including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization.[1] It includes nicking of the clitoris (symbolic circumcision), burning or scarring the genitals, and introducing substances into the vagina to tighten it.[49][50] Labia stretching is also categorized as Type IV.[51] Common in southern and eastern Africa, the practice is supposed to enhance sexual pleasure for the man and add to the sense of a woman as a closed space. From the age of eight, girls are encouraged to stretch their inner labia using sticks and massage. Girls in Uganda are told they may have difficulty giving birth without stretched labia.[l][53]

A definition of FGM from the WHO in 1995 included gishiri cutting and angurya cutting, found in Nigeria and Niger. These were removed from the WHO's 2008 definition because of insufficient information about prevalence and consequences.[51] Angurya cutting is excision of the hymen, usually performed seven days after birth. Gishiri cutting involves cutting the vagina's front or back wall with a blade or penknife, performed in response to infertility, obstructed labour and other conditions. In a study by Nigerian physician Mairo Usman Mandara, over 30 percent of women with gishiri cuts were found to have vesicovaginal fistulae (holes that allow urine to seep into the vagina).[54]

FGM harms women's physical and emotional health throughout their lives.[55][56] It has no known health benefits.[9] The short-term and late complications depend on the type of FGM, whether the practitioner has had medical training, and whether they used antibiotics and sterilized or single-use surgical instruments. In the case of Type III, other factors include how small a hole was left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, whether surgical thread was used instead of agave or acacia thorns, and whether the procedure was performed more than once (for example, to close an opening regarded as too wide or re-open one too small).[7]

Common short-term complications include swelling, excessive bleeding, pain, urine retention, and healing problems/wound infection. A 2014 systematic review of 56 studies suggested that over one in ten girls and women undergoing any form of FGM, including symbolic nicking of the clitoris (Type IV), experience immediate complications, although the risks increased with Type III. The review also suggested that there was under-reporting.[m] Other short-term complications include fatal bleeding, anaemia, urinary infection, septicaemia, tetanus, gangrene, necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating disease), and endometritis.[58] It is not known how many girls and women die as a result of the practice, because complications may not be recognized or reported. The practitioners' use of shared instruments is thought to aid the transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV, although no epidemiological studies have shown this.[59]

Late complications vary depending on the type of FGM.[7] They include the formation of scars and keloids that lead to strictures and obstruction, epidermoid cysts that may become infected, and neuroma formation (growth of nerve tissue) involving nerves that supplied the clitoris.[60][61] An infibulated girl may be left with an opening as small as 2–3 mm, which can cause prolonged, drop-by-drop urination, pain while urinating, and a feeling of needing to urinate all the time. Urine may collect underneath the scar, leaving the area under the skin constantly wet, which can lead to infection and the formation of small stones. The opening is larger in women who are sexually active or have given birth by vaginal delivery, but the urethra opening may still be obstructed by scar tissue. Vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae can develop (holes that allow urine or faeces to seep into the vagina).[7][62] This and other damage to the urethra and bladder can lead to infections and incontinence, pain during sexual intercourse and infertility.[60]

Painful periods are common because of the obstruction to the menstrual flow, and blood can stagnate in the vagina and uterus. Complete obstruction of the vagina can result in hematocolpos and hematometra (where the vagina and uterus fill with menstrual blood).[7] The swelling of the abdomen and lack of menstruation can resemble pregnancy.[62] Asma El Dareer, a Sudanese physician, reported in 1979 that a girl in Sudan with this condition was killed by her family.[63]

FGM may place women at higher risk of problems during pregnancy and childbirth, which are more common with the more extensive FGM procedures.[7] Infibulated women may try to make childbirth easier by eating less during pregnancy to reduce the baby's size.[64]:99 In women with vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae, it is difficult to obtain clear urine samples as part of prenatal care, making the diagnosis of conditions such as pre-eclampsia harder.[60] Cervical evaluation during labour may be impeded and labour prolonged or obstructed. Third-degree laceration (tears), anal-sphincter damage and emergency caesarean section are more common in infibulated women.[7][64]

Neonatal mortality is increased. The WHO estimated in 2006 that an additional 10–20 babies die per 1,000 deliveries as a result of FGM. The estimate was based on a study conducted on 28,393 women attending delivery wards at 28 obstetric centres in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan. In those settings all types of FGM were found to pose an increased risk of death to the baby: 15 percent higher for Type I, 32 percent for Type II, and 55 percent for Type III. The reasons for this were unclear, but may be connected to genital and urinary tract infections and the presence of scar tissue. According to the study, FGM was associated with an increased risk to the mother of damage to the perineum and excessive blood loss, as well as a need to resuscitate the baby, and stillbirth, perhaps because of a long second stage of labour.[65][66]

According to a 2015 systematic review there is little high-quality information available on the psychological effects of FGM. Several small studies have concluded that women with FGM suffer from anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.[59] Feelings of shame and betrayal can develop when women leave the culture that practises FGM and learn that their condition is not the norm, but within

Tanya Virago Is A Bukkake Natural

Cfnm Sex Hd

Tits Fucking

Trans Cums Out Of Him

M Condom

Female genital mutilation - Wikipedia

Female Circumcision - The Difference between Female ...

Female Circumcision

/%3Cimg%20src=)