Fatherhood, I Now Learn, Is a Young Man’s Game

@americanwords

The first time in my life I had unprotected sex, one August night three summers ago, I was 45. No pill or condom, no diaphragm or IUD — none of the sundry devices deployed to keep me careering, childless, through a quarter-century of romance with women I had lusted after and sometimes loved. This time the woman was my wife, Molly, and we had decided to have a baby.

Molly was nine years younger than I, and we’d been together eight years. About children, we agonized for a long time; then we agonized about agonizing. Deciding in midlife to become a father unfolds in a series of trenchant recognitions. A friend at a college reunion says, “O.K., you’ve lived one of your two lives, now what do you want to do with the one that’s left?” Or someone falls ill, or dies. Several months before, Molly’s brother had been given a diagnosis of lung cancer, and my mother was experiencing a spate of mysterious symptoms that would turn out to be the same terrible disease. Much more acutely than I would have at 25, or even 35, I felt the presence of ultimate things.

The prospect of life and death in the balance brings a metaphysical dimension to what I began calling “late-onset fatherhood.” One day at the gym I showered next to a guy busily shampooing his 4-year-old son. “Not on my forehead!” the boy cried. “Why not?” his father asked — and before the boy answered, I knew exactly what he was going to say: “It gets in my eyes!”

With perfect clarity I recalled the outrage of that stinging discomfort, and my own father saying, exactly as this father now said, “Then close them!” I thought about how having a child extends you through time — genetically into the future, but also into the past, reconnecting you to perceptions and experiences you have all but forgotten. I felt tired of living only in the present.

The physical side of late-onset fatherhood was less thrilling. There’s a keen incongruity in trying to open up this huge new dimension in your life, even as life announces its intention of closing you down, starting with your physical prowess.

Already I was feeling pretty creaky, the consequence of a nasty basketball habit I couldn’t kick. Ankle sprains, back spasms and, finally, the mother of all sports injuries, a torn anterior cruciate ligament. “Now, you can either alter your lifestyle to fit your knee or alter your knee to fit your lifestyle,” the surgeon said. Hmm.

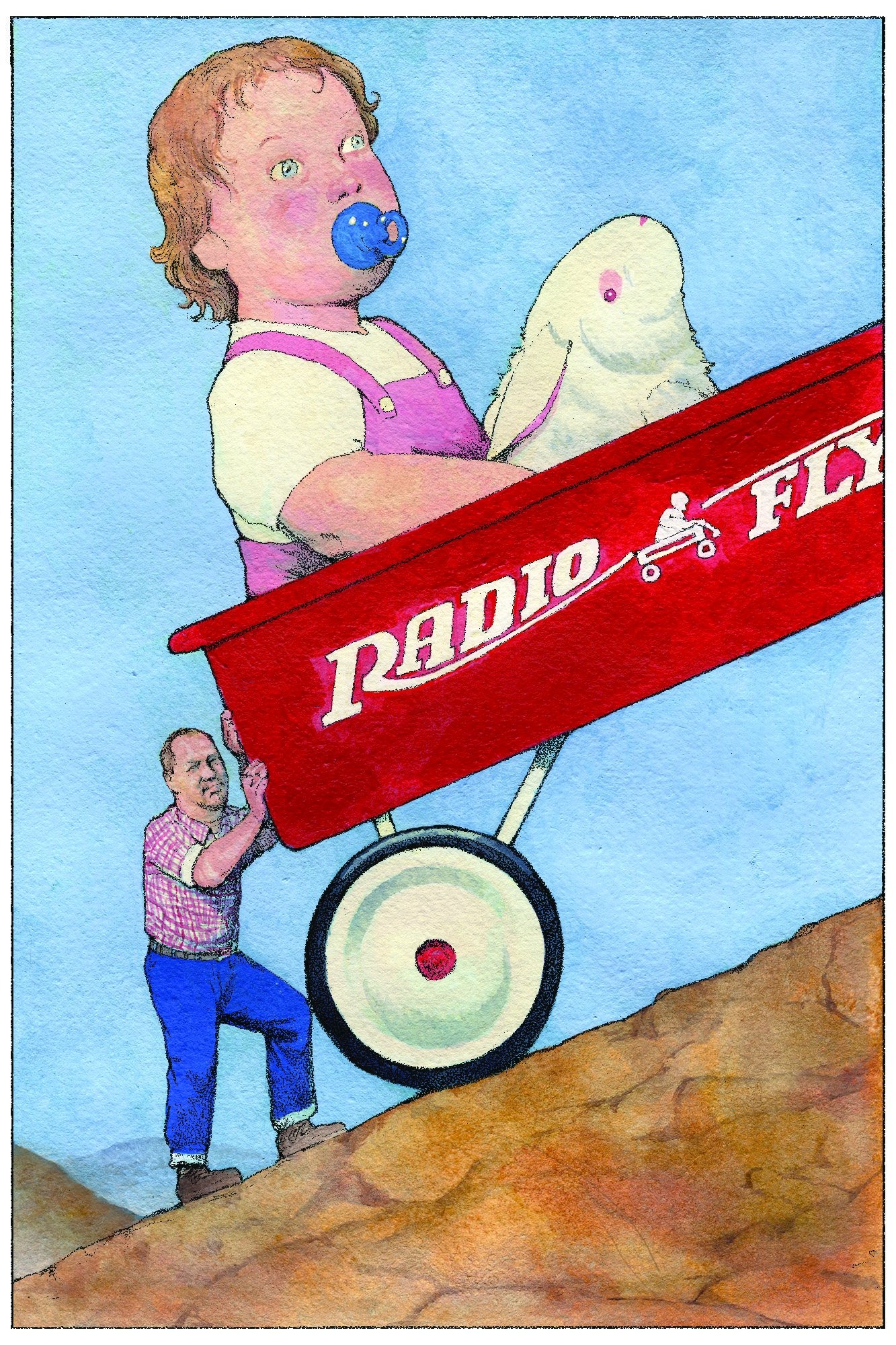

The belated father faces a daunting gamble. Will a baby indeed keep you young, open up some replenishing new vitality? Or will it do just the opposite? Will I have the energy to be an older father? The patience? The knees? In the unsentimental terms of evolutionary psychology, would becoming a father prolong my peak and delay my plummet — or, as a middle-aged man playing a young man’s game, was I merely setting myself up for an even bigger fall?

That autumn, as Molly and I were helping friends drop their daughter off at college, I saw a geezer father amid the throng of parents, hobbling alongside his son. “You’re looking at me,” I said to Molly. I did the math. Even if we got pregnant tomorrow, I’d be pushing 70 when our child graduated from college.

And we weren’t getting pregnant tomorrow. Nature was playing its cruel trick on those who wait: For years you wouldn’t and now, it seems, you can’t. Six months went by, a year; nothing. Nothing but the pregnancy test kit, with its dreaded Thin Blue Line, that kept telling us no, not yet, try again. After 18 months we handed ourselves over to the fertility industry. For Molly, ultrasounds. For me, semen analysis. I had become obsessed with doubt about my 46-year-old sperm. All those decades I’d spent thwarting biology — wasn’t there bound to be payback?

In adversity you fall back into primitive thinking, full of self-reproach and neurotic bodily metaphor: my stream diverted and grown fetid; my once-robust vintage now sadly corked, turned to mold. Waiting for the doctor’s office to call with my results, I made the mistake of consulting a semen-analysis Web site, with its nightmare list of abnormalities: hematospermia (blood in semen); asthenozoospermia (poor motility); and creepiest of all, necrospermia. When the phone rang, I was gaping at drawings of sperm with shriveled heads or two tails, a gallery of misshapen monsters.

But nothing like that showed up, and eventually came a warm spring morning when Molly rose early after a restless night. From the bathroom came the sound of trickle, trickle. I followed her in. The little pregnancy-test wand sat on the side of the tub. We peered at it.

“Oh my God,” Molly said.

SO much still awaited us, but at least we were done waiting for the waiting; and I found myself eager to say goodbye to life as I knew it. That same day, while leaving the gym — driving out of the parking lot in my convertible, top down, tunes blasting from the car stereo — I passed a guy loading two kids into a minivan. He was a few years younger than I, and as I went by, he looked my way with a big rueful smile, gesturing back and forth. “You take mine,” he was saying, “and I’ll take yours.” Meaning the kids, the car, the life.

I knew how I appeared to him, a man emerging from fatherhood into the sunlit freedoms of midlife. He was thinking he couldn’t wait to be me. Little did he know, I was smiling like a crazy fool because I was about to become him.

Fast-forward nine months — past the fathomless sorrow of the death of Molly’s brother, past the thrill of our first shadowy ultrasound and the comedy of parenting classes where I would burp a plastic doll alongside fellow fathers-to-be, some of them closer in age to their impending babies than to me — to a sunny afternoon in January. That was when our daughter, Larkin Fehr Cooper, uttered her first squawk, in Room 646 of the appropriately named Bliss Building at Hartford Hospital.

The maternity ward practiced the rooming-in concept, whereby the husband, formerly that awkward auxiliary figure drinking coffee in the hallway, now can be in on the action. Our room came with a cot, and I spent that first night dozing to Van Morrison, Larkin on my chest, making aimless little jerking movements. Filing her tiny fingernails with an emery board, sharing a pizza as she slept alongside, Molly and I felt the sweet intensity of being new parents cocooned with a baby. Time stops, the world with its news and duties recedes, and the three of you experience an ecstatic, ferocious tenderness that takes familiar old emotions and mixes them in powerful new concoctions. “I feel like we’re being reprogrammed,” I said.

And yet I was still the same old person — as events all too soon reminded me. Our very first day home from the hospital, fetching Molly a glass of juice in the kitchen, I bent over to take an ice tray from the freezer, when, wham! Someone kicked a dagger-toed boot into my lower back. I went down, ice trays flying. These were the same back spasms that felled me on the basketball court a year ago. I couldn’t get up, couldn’t even sit up. The pain was too intense.

“Not now,” I thought. Not when Molly still had her stitches in, and needed to be resting with our baby. Not when I intended to wait on the two of them, hand and foot. I wanted to be the do-everything guy, and now I was going to be the do-nothing guy, bedbound for the next three days: an invalid, whose wife would have to bring him his medicine and carry his urine to the toilet in a bucket.

Lying there, I writhed in a misery that verged on despair. For 72 hours life had been serving up sweet joy and exaltation, but right now all I could think about was my failure as a father. I recalled years of boyhood sports fun with my own father — epic battles of one-on-one basketball, marathon tennis matches on hot summer days, followed by a race to the beach and a leap into the water.

My child, I was convinced, would never have that with me. Larkin would know me as a fragile, gray, grandfatherly presence. As for her actual grandparents, she would experience them barely, or not at all. I had known my grandparents well when I was a kid; two of them had seen me into adulthood. Larkin would miss out on that. And it was my fault, all of it. I had waited too long. I had selfishly hoarded the vigor of my life and used it up on myself.

Molly found me lying on the kitchen floor, weeping tears of rage. She held my head on her lap.

“I wanted to do everything,” I said. “And now I’m useless.”

“It’s O.K.,” she said. “I love you so much.”

I knew she did, and thank God for that. But would it be enough? I pictured Larkin, asleep in the bassinet upstairs. She was so tiny. I felt so old. There was such a long way to go.

Our house has a first-floor guest room, just beyond the dining room and down a short hallway, with a queen-size futon. I saw my journey there as if from an ant’s-eye view, looking up at the legs of the dining room table, the handholds on baseboards and door frames.

From upstairs came the sound of our brand-new baby, screaming to be nursed.

“Go,” I said to Molly. “But first I need you to get me the Vicodin and the Flexeril.”

She did; and so began the great adventure into late-onset fatherhood, as I gulped the painkillers and crawled, whimpering, across the kitchen floor.