Everything is Intertwined

kunokumo

"Time flies so fast in Japan" — is what all foreign students keep telling me here in daily conversations. This sounded ridiculous at first, but lately I've been feeling that I can't really distinguish between yesterday and the day before it, as well as last week and the one before. In Europe 15 minutes seemed to me like a big deal — one could take a solid coffee break or cover a significant distance on public transport to get somewhere you need. In Tokyo 15 minutes is just a gap big enough to change trains or get from home to the station. Here I don't even consider having a coffee — forget getting anywhere in the city — with this amount of time on my hands. Generally speaking, Japanese concept of time is not equal to western. Sure, it is still linear but people tend to perceive it in a more cyclical form. Time is not money here, time is a procedure. Oh, but I'll get to that point a bit later.

This morning my usual 15-minute walk to the station turned out quite meaningful. I was strolling along an elevated railway, usually covered with wild grass swaying impressively on especially windy days, when I caught a painfully familiar scent in the humid heavy air. "Summer", the thought came to me almost mechanically. "Summer is already in full swing”. It was the smell of freshly cut grass left in small chunks around the railway, drying in the late afternoon heat. I stopped to better process the revelation: I've been here for three months already. No way! I’ve seen the infamous cherry blossoms, felt the cold of April nights, typhoon winds in May and just survived the rain season. Why wasn't I able to feel the time pass more clearly? [Now when I am finally posting this text, that grass on the railway is completely burned out after a disastrous heat wave].

Not that I was enjoying myself too much; there's quite a lot of things to do at university, dorm chores, part time job, thesis research (which now became something completely different from it's initial form but I’ll write about that later), some captivating events, and even choosing a place to eat out everyday can often require a lot of energy, too. Most of the times I come home so late and tired that I can only lay still and listen to chill out playlists or read stupid manga to reach an emotional standstill so that I can finally fall asleep. I can't say I am being very productive in my studies, in terms of sheer quantity I am doing at least 3 times less stuff than last semester in Milan. So it seems that my problem of time acceleration arises from losing at least two hours everyday to commute, struggling with Japanese ways of doing things (studying, paying bills, going through administrative issues, procedures, procedures, procedures!) plus spending solid several hours a week to translate all the menus, use instructions and product labels everywhere. Yeah, most people still don't speak English here — hospitals, police, department stores, pharmacies — you will have trouble everywhere if you have a tiny bit of problem that needs some kind of non-binary explanation.

I also stopped doing anything productive on the trains since in the evenings it's almost impossible to find a seat, and in the mornings I'm just too sleepy and end up dozing off. This time is kind of exceptional because I'm writing this on my journey back home as I managed to miraculously secure a seat in a train full of salary men at freaking 22:30. And damn it, now I already need to change to another crowded line. The rush hour here starts around 16:15 on weekdays and almost never ends until the last train.

However, these everyday trips gave me a wonderful opportunity to think. Never in my life did I spend so much time inside of my head on a daily basis. Watching Japanese suburban scenery behind the windows puts me in a kind of special meditative-contemplative state of mind. It reminds me that I am in a place very distant and tremendously different from where I used to be and doing something quite far from what I used to do up until now. This realisation excites me all the time, so apart from my usual personal aspirations, I often think about possible reasons that make Japan (especially its architecture and social norms) so different (not always in a good way) from anywhere else I’ve been to and why art universities are so freaking confusing (not always in a bad way, really) compared to technical ones. After so much thinking done I have many things to tell you. Since they’re quite disconnected and I can’t even remember when exactly they occurred to me, this chapter will be more like a compound of brief stories. I'll begin with everyday life topics and next time I'll try going into more peculiar stuff. Let me know how you find it later in personal feedback.

Now let’s start from the weirdest one, since we're talking Japan here huh!

You Can’t Turn Off The Camera Sound in Japanese Phones

Or Some Disadvantages of Being a Woman in Japan

Last month my host professor here invited our laboratory (consisting of 9 people including myself) to a “beginning-of-the-year dinner” at his luxurious self-designed house. The tradition of having various parties to start the academic year in Japan is a kind of sacred thing. There is always a whole array of them, all having different level of grandeur. The first one is usually for the whole faculty where the first-years organise the pre-fest on university grounds with embarrassing initiation competitions on an improvised stage accompanied by cheap drinks and snacks, while seniors and teaching assistants take everyone (we’re talking 60-70 people here) for a loud dinner in a nearby casual style restaurant, of which you might have seen some photos in my second post. There’s also a second edition of this event month later in which the first part has to be staged by one laboratory (they take turns every year) and that looks more like embarrassment-oriented Japanese TV shows where participants have to take off their clothes if they fail a stupid quiz, throw bananas at each other and shoot water blasters. I’m not exaggerating.

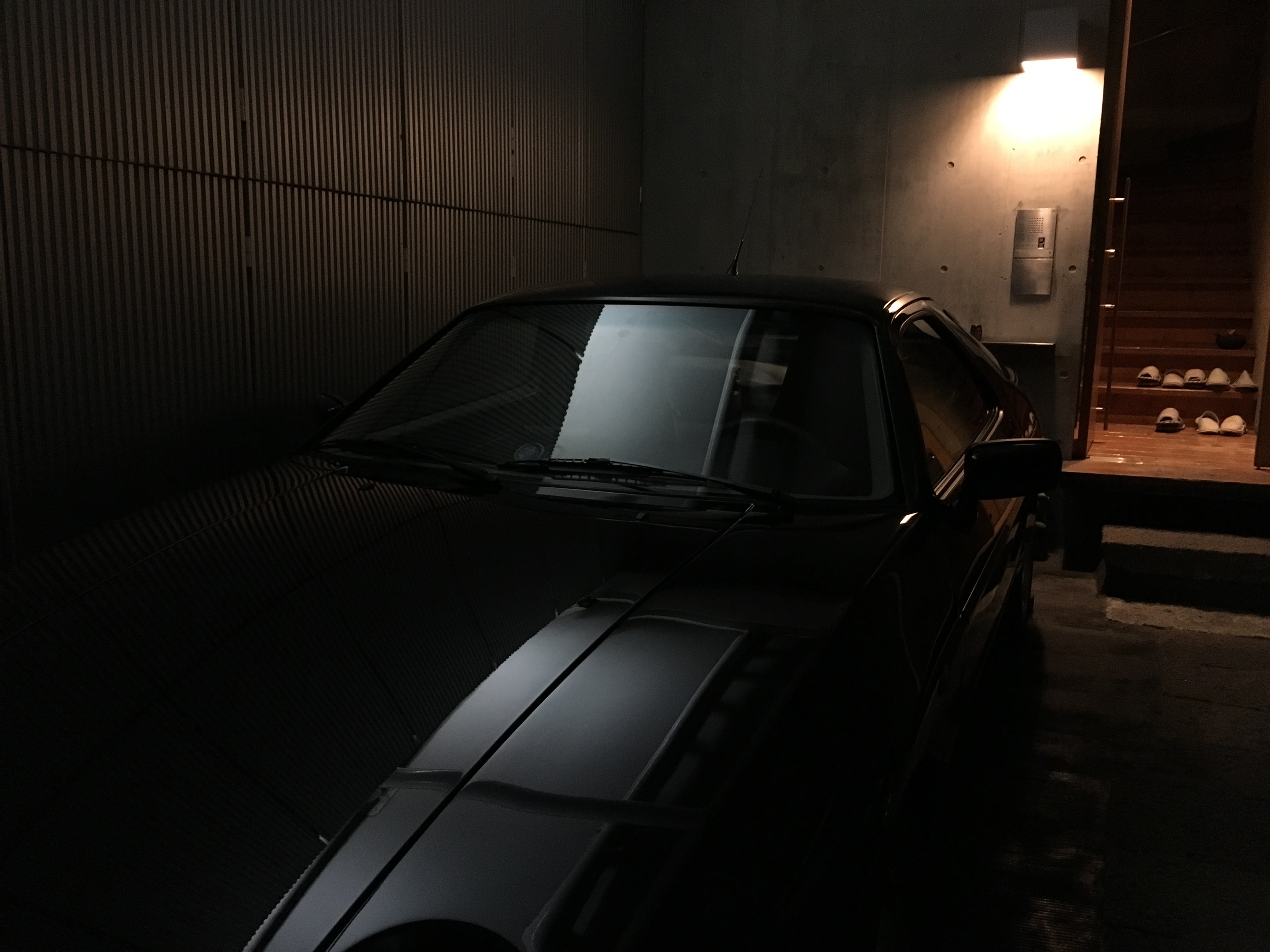

After all this settles down, there are smaller parties every laboratory tends to have, usually sponsored and organised by the lab’s professor and those have a more serious atmosphere. Ours was way too serious though, as our prof — being a nationally established tremendously successful archistar — invited us for an official dinner at his refined four-story concrete mansion in one of the most beautiful areas of Tokyo. I felt awkward already at the entrance squeezing between two shiny porsches to get to the door, one of which appeared to be a rare retro model. My lab mates became very tense, and I can only imagine how they felt given their culturally embedded worship of seniors and success in Japan.

The highlight of the dinner was a tea ceremony performed by professor’s wife, who graciously poured matcha tea produced especially for the emperor’s family (and obviously impossible to buy if you’re an ordinary mortal being) into national heritage ceramic pottery. When I was told that the cup I was holding probably cost more than anything else in this house (think about the cars, oh god) I almost choked on my tea. Just a note to fellow architects: everyone sat on Corbusier LC1 and Cassina 412 CAB chairs. But it was just the beginning; then we discovered that the dining table was made from a whole slice of a 150-million-year-old stone, one could actually see hundreds of fossilised shells on the surface. Of course we were dying to take photos but it seemed totally inappropriate for the occasion. However, my will completely broke down when we were shown to a penthouse-like glass box on the roof containing a huge bath in the middle, surrounded by dense tropical vegetation from all sides. I took my pictures inconspicuously with the sound off, but after the professor left the room, my Japanese comrades started using their cameras with the loudest sound mode possible. It was certainly clearly heard from downstairs. I asked why couldn’t they turn the volume down and found out that it is just technically impossible for any Japanese phone (iPhones as well!) because of… an anti under-skirt-photos policy. I had to reconfirm it with Google but yeah, that’s a real thing.

Now that I think about it, at first I was amused to ride in women-only train cars full of female-oriented ads and exhausted salary women, but after a while I started to see the reasons behind all this. I grasped just how deeply women are sexually objectified in Japan. Even with their mass rule obedience and highly developed concept of self-dignity and respect, they still have a veeeeery long way to go in terms of gender equality. And objectification with sexual harassment are just side symptoms in the big picture. Women here are not paid equally, are not given equal opportunities, are seriously underestimated in all kinds of situations and nobody bats an eye like they would in Western countries. My friends from the dorm say that if you want something done quickly and easily in any kind of institution or public facility as a woman, you better bring a man with you. Sometimes it gets just a bit too inhumane here, especially with the work-environment in big companies and domestic violence stories I happen to hear and see (it's quite common to spot neatly dressed married women with dark bruises all over their faces in metro). If all that is still too far from you, then I can assure you in my university there are only male professors in our department. Okay, you might say, just a coincidence, but two years ago the first female professor, a cool progressive architect loved by all the students, left after just one year of teaching for "unspecified" reasons (quite obvious anyway and still discussed by students in a low voice). I also visited a few middle-sized architectural studios in Tokyo that "inadvertently" don't hire any women. Sure they can do internships but real jobs seem unobtainable unless you're a Pritzker-level female genius. Fortunately, it's getting less and less common, but yet again, architecture is a much freer world by its nature than that of academics or finance, for example. Fellow women, never do finance in Japan, never, okay? Actually, stay away from all Japanese corporate culture. Alright, we started with the dark sides a bit too early, moving on to some positive vibes next!

Don't Worry, It All Comes Back

But Always with a Certain Procedure

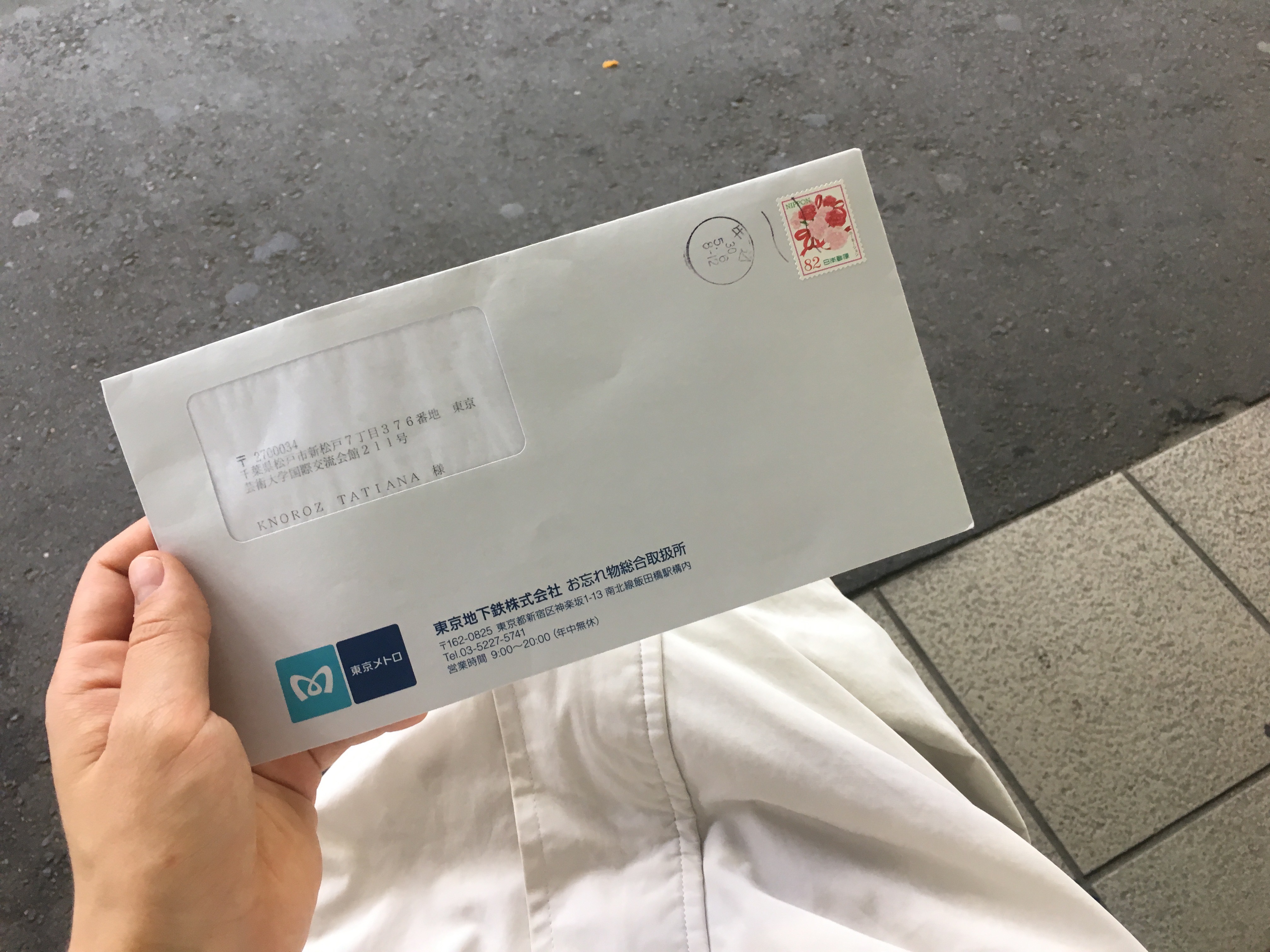

One night I was coming back home late after meeting a friend in a very distant neighbourhood and realised I don’t have my wallet with me anymore. In Japan under the fear of an approximately 2000-Euros fine you are required to carry personal immigration documents with you at all times, so of course all of it was always in my wallet, as well as all credit cards, university ID and some cash. I was terrified; not only I couldn’t remember where exactly I left it, I realised that I changed three metro lines and I had no idea where to start looking for it. The next day I went to all the stations where I transferred asking around the attending officers but they had to clue. My university friends advised me to fill out a report at the police and wait patiently. “Don’t worry, it’s Japan, it all usually comes back.” I did as they told but, of course, I wasn’t that optimistic and started some preparations for recovering my residence card. Three days later I checked my postbox for the usual utility bills and found there a very neat enterprise-style envelope with “Tokyo Metro” logo and a cute postage stamp on it. I only buy my monthly passes with Japan Railways and Tsukuba Express so I was a bit surprised to get a letter from another company, until I opened it and found a short message in Japanese, saying:

“Dear passenger, we found an item belonging to you in our premises on this date. If you’re not too busy, please be as kind as to retrieve it from our Lost&Found office in three days, otherwise we will hand it to the Metropolitan Police and they will follow their own procedure of delivery.”

I almost cried. When I reached their office and showed the letter, the attendant took out a transparent folder containing my wallet, a plastic box and an envelope with some paper forms in Japanese. After I filled out the forms, the man opened the envelope and counted out in loud voice all the banknotes found in my wallet placing them carefully before me on the table. Then he proceeded with the box, where all my coins were neatly organised in stacks. He meticulously counted every single coin and damn I had tons of them, especially those of one-yen value. It was almost irritating, I even tried to stop him but he couldn’t disregard the sacred procedure. Finally I signed that the amount of cash was the same as before the loss and put it all back inside. I already told you how crime-free and safe Japan is, but this incident amazed me anyway. When asked why they decided to move here, lots of foreigners I met list safety as their primary reason. And the second comes next.

Japan Is Crazy About Convenience, Cleanliness and Cuteness

And May Be I Know Why

Last Sunday I had quite a hangover and stopped by a nice ramen shop near Ueno station. Almost all of Japanese food is actually designed to cure hangover symptoms (an average Japanese will definitely outdrink any Russian in terms of weekly alcohol consumption), but ramen is the ultimate panacea — it literally resets your body functions and after a few hours you feel alive again. The only difficulty with ramen for me is that it is a traditionally “manly” fast-food dish here (yeah, one of the above mentioned Japanese social issues), so most ramen stalls are full of scary salarymen who would always stare at me with curiosity and disbelief when I sit alone beside them.

Therefore, I usually tend to go to smaller and slightly more secluded places, where you could often spot couples and salary women as well. I was almost finished with my bowl, when a young couple occupied two seats nearby and made their order. The girl looked a bit too neat for a ramen shop on the backstreets, wearing an elaborate make up and having her well-taken-care-of long hair hanging untied. Still suffering from headache and having nowhere to hurry, I lazily observed them until they got their bowls and started eating. Suddenly, the cook behind the stand made a quick gesture in girl’s direction and asked her to wait. I thought he forgot to add some kind of ingredient, since he opened an overhead cupboard and took out a nice little box. He opened it gallantly in front of the girl. I bent my head in curiosity to find out what was there and saw a selection of black hair ties inside. I couldn’t really grasp the meaning of the situation until the girl took one tie, thanked the cook, arranged her hair and continued eating as if nothing happened.

That was just a preface though; you can’t even start to imagine how thoroughly everything is designed for comfort and cleanliness in this country. Conbini (that are convenience stores) are the greatest quintessence of Japanese urban and suburban life. Omnipresent, open 24/7, selling ready-made meals in vast variety, prepackaged hot and cold drinks, freshly grounded coffee from automatic machines, fried chicken, boiled eggs, hot soup, ridiculous choice of alcohol in all kinds of sizes and every daily essential imaginable including laundry liquids, sanitary napkins, towels, socks, underwear, you name it! You can always pay your utility bills, withdraw money and buy latest press — every evening all suburban conbini are full of silent salarymen reading manga magazines standing in rows, obviously trying too hard to save money. Moreover, you can have free hot water for instant noodles and use microwaves, as well as toilets that are always unbelievably clean.

I think now I am able to write an entire chapter about Japanese public toilets which could be found absolutely in every station and everywhere on the street, free of charge and highly technologically advanced. It is a very usual case to encounter a WC with a built-in bidet, sanitising treatments, heated seat and a button for flush sound simulation (yeah, exactly) that serves to conceal your personal business from the neighbouring cabin visitors. Every girl in my university switches it on right upon entering the cabin, even if there’s no one nearby, which used to make me feel kinda awkward for them. As a western person at first I found it meaningless, especially since this amount of buttons with kanji is terribly confusing, but at the end I grew to acknowledge this drive to make everyone comfortable. My personal favourites, however, are bathrooms in bars and restaurants, where you can also find fancy hand lotions, mouthwash liquids, pads, cotton swabs, disposable hair and tooth brushes along with toothpaste and sometimes even spray deodorant. It’s as if they presumably foresee that you might spend the night at your new date’s place and need some personal care items and fresh breath before you set out. That’s some ultimate customer care.

About actual customer care — it is almost flawless. Case 1: I was trying out different waterproof eyeliners on my hand in a Japanese makeup store, then drifted to another shop next door and ended up buying a shampoo there (they have terrible shampoos that leave your hair heavy and oily so it was my third attempt already). The shop assistant stopped me before I left and pointed on my hand which was completely covered with black eyeliner marks. I was confused and tried to leave again but she took my hand, found a cotton pad and a washing liquid in her desk and started to clean it patiently. Needless to say it took quite some time to wash off waterproof eyeliners and some very light traces were still left, for which she sincerely apologised. Twice.

Case 2: I bought a simple T-shirt on sale in a slightly high-end store (fun fact: Japanese mass fashion brands don't sell women clothes with deep necklines, which are the only ones that actually suit me so I spend ages looking for a damn simple white top). The shop assistant brought the same model wrapped in plastic bag from the storage, made sure I inspect it for quality and loose threads, packed it beautifully in paper (10 minutes of perfection, oh those sweet procedures), and when I tried to take the bag she refused to hand it over and showed me to the exit. I was confused x2. She called the second assistant and together we walked until the door, where they both faced me and bowed simultaneously. This 90-degree bow was a first time for me, before I only participated in generic 45-degree ones. Then I was given my bag and they repeated the bow again with a big smile. At this point I also bowed but taken by surprise I could only do my usual small casual bow and felt terribly awkward as I walked away.

It's clear that this refined air of hospitality and customer service is coming from historically strict hierarchy of society going down from Emperor's court to an individual family that produced high standards for people's behaviour towards their superiors. But what about these crazy WC and other convenience obsessions?

From what I could observe in Japanese traditional culture, the drive towards supreme comfort and thorough provision of human necessities seems to flourish from the idea of preserving one’s cleanliness at all times. But why being perfectly clean is so important? At first I felt it all comes from Shinto and Buddhism beliefs, which thousand years ago made people abandon their capital city and relocate to a new place as soon as the ruler died thus “polluting” the palace and its premises. Yeah, dying is no good even nowadays, when apartments where someone died recently are sold 3 times cheaper and still don’t have any buyers. (By the way, all real estate agents are obliged to tell if there was a death in the house to potential buyers by law.)

But Shinto is not the only answer, actually, it's just a consequence of another simpler thing. After I experienced an unbelievably muggy hot summer in its full taste and finished a book on history of Japanese architecture, I have a better guess. HUMIDITY. Throughout the year it's already higher than anywhere else I've been to, but from June to September it reaches levels when your long hair can actually mildew if not properly dried. Crazy, right? So if you can have fungus on your hair just imagine what happens to any kind of solid wall in your house. Most of materials apart from certain kinds of mold-resistant wood would basically self destruct in a couple of summers like this. And then just add the yearly rain season and typhoon periods to all that - not only your house but everything in it will rot from the inside unless properly taken care of. I consider this as the main reason why Japanese architecture is so structurally and visually different from continental. Light ventilated spaces, no unnecessary furniture, every part is easily replaceable if decayed.

No wonder that average life of a building here is just 15 years before it’s demolished, since even properly constructed houses will still have issues with this climate over time. The only way to solve the problem of fungus and insects (yes, these bloody creatures add up to the total destruction) is to get rid of your dwelling and build a new one. After you know this it's a bit easier to understand why in Heian period entire capitals were willingly abandoned to start from scratch somewhere else. Shinto beliefs that seem to justify this are just based on common sense and accumulated environmental adaptability of local people. But since cleanliness became a part of religion, it stopped being imposed only on cities and houses and went much further than that.

Japanese love having a perfectly clean body, sometimes going a bit overboard by my standards. If your place doesn’t have a bath, you are considered a total low-lifer. Even my tiny dormitory room has a bath with instant gas water heater, which encourages me to wash more often than I would do in Italy with limited hot water coming from a 8-liter boiler. Every small supermarket has a selection of bath salts, washcloths and body scrubs. And you wouldn’t imagine the variety of cosmetics and cleaning products they sell in pharmacies and specialised shops! Yesterday I found out that they have nearly as many brands of feet deodorants as armpit ones and sometimes it’s tricky to tell one from the other.

In my university building we have a nice shower and architecture students frequently use it when they stay overnight. All my Japanese peers have their shampoos, body lotions and towels ready on their personal shelves. We also have a sink right inside the lab room where everyone keeps their toothbrushes and contact lens liquids. The most amusing discovery I made in this field is that men here are as crazy about their skin as women — my lab neighbour happily bragged about his new face cream that he bought online when he had it delivered directly to his desk. It is also completely normal for males in Japan to buy skin scrubs and apply face masks. Yeah, and why not? Well, it may be nice to have smooth and shiny cheeks, but to me some guys here look just a bit too perfect and doll-like to date. Just personal preference though!

So Japanese people always strive to be clean&fresh and if for some reason something goes wrong — there’s always a 24/7 conbini store nearby where you can buy a new white T-shirt or socks (only men stuff though, sexism in full bloom for ya), toothbrush, napkins or tampons (which by the way are always carefully wrapped in a separate paper bag by a considerate cashier as if something to be ashamed of), adjust yourself and puff! — your dignity is instantly recovered. However, all this just illustrates how high is the pressure of culturally imposed conventions here. You are expected to be nothing less of perfect in everyday life, especially women, who always nervously check their (absolutely perfect by my evaluation) make up on the trains staring in tiny pocket mirrors and correcting the shape of eyelashes with special brushes. I always fail to notice the resulting difference and feel like I will never truly belong in this country. Especially because there are more reasons for that.

Visually Pleasing but Twisted from the Inside

Welcome to the Dark Side

While you might first be fascinated with Japanese food, city scapes, cleanliness, convenience of various services and infrastructure, entertaining exoticism of customs and human behaviour, beauty of peculiar island nature and unmatchable cuteness of Japanese girls and all the other things that local immigrants happily brag about in their thematic blogs, after a certain period working or studying here and learning fellow foreigners’ experiences, you start to get a deeper and darker picture that dissolves your initial wish to stay in Japan for the rest of your life. It makes you clearly see that this stuff only makes you happy if you don’t have to interact with the surrounding Japanese society and any kind of human-based system here in general.

Learning the language would be just half of the trick to have a decent quality of life in Japan. Just note that while I could learn Italian well enough to have a meaningful dating relationship after just 2 months of living in the country, here I’m still on the 3-year-old level in terms of speaking. Even though 6 years of watching various Japanese content with subtitles helped me to kinda get some parts of the lectures (I’m taking five courses in Japanese so I practice listening almost everyday) and general topics of people’s dialogues, I barely manage to explain myself in shops. Even though my lab partners and assistants joke about how I can often understand what they say unexpectedly, I only get the useless casual parts and not the main meaning. Sometimes I can even wedge into a daily conversation and add a couple of simple comments, which would amuse my peers very much but honestly this is not helpful in real life struggles at all. For example, I ended up cutting my hair myself twice (quite miserably I'd say) since I had no idea how to explain what I wanted at hairdresser's. Now I totally understand why people don't cut their own hair.

However, listening and speaking is just the tip of an iceberg — I happened to meet an extraordinarily talented person who has been living here and speaking Japanese everyday for seven years straight at university and with his partner, but he still has some occasional difficulties with reading, and he admits that writing any kind of serious text correctly is almost impossible without years of professional full time language training. So just imagine being unable to understand texts in important documents, literature or magazines and write in the country you are now — how would that affect the level of your life’s comfort?

Realising this difficulty used to make me frustrated at first but now I’ve started to ask myself: even if I spend years learning Japanese and somehow manage to succeed, is it really worth it? I'll tell you my perspective on this.

Let's say you manage to learn the language and move in - in the first months you'll be enjoying the views, excellent customer service and politeness, perfectly clean streets, safety, exotic food, trains being always on time, stuff like that. In case of Tokyo, your time will flow faster and you'll never feel bored. All that will distract you for quite some time. If you get an interesting job or enjoy our studying too much - for even more. You'll have fun drinking with your new Japanese colleagues that would seem friendly and outgoing at first. But my bet is after a couple of months you'll start wondering why they still remain on superficial terms with you and refrain from deepening the relationship. So one day you'll return with the last train after a long day at work, probably hungry because you're already fed up with all the eating out options on your way home and prepackaged supermarket meals, immeasurably tired of bowing, smiling, not understanding the intended meanings between the lines, of being extra careful not to offend anyone anywhere, of fitting into hierarchy and being on its definite bottom in any kind of institution (as a foreigner and therefore outsider), of feeling various prejudices against yourself everywhere in daily life and of not having meaningful relationships. Of course, it's all very personal and I am only speaking for myself, but at the same time, I haven't met any foreigner who was genuinely satisfied with his life here. While some were incredibly happy about their job, they admitted to have no outside life whatsoever. In fact, most of Western immigrants after a certain while grow to feel that their presence here is very temporary (since they're socially unhappy and want to leave at some point) and that makes it problematic to find any lasting relationship or friends even among foreign people. Guys who tried going out with Japanese girls told me quite unsettling stories of constant misunderstandings, "template" behaviour, insincerity and "multiple boyfriend system". Yeah, cheating here is kinda normal and something you would expect even from married couples with kids. I am planning to write a big text on red-light districts, host clubs, love hotels and Japanese married life later so you'll definitely have a better picture. Sad and twisted picture, that is.

May be it's just Tokyo and my suburban train line, but the amount of frustrated single people in public transport is scary. It gets especially depressing on last trains every Friday night when clearly everyone is drank and barely standing but alone, sad and quiet. When you get out of the station, you see the above-mentioned rows of men reading erotic manga magazines in a local convenience store at midnight. You never get this atmosphere of friendly vivid urban wellbeing like in Italy where lots of people are smiling, chatting on the streets and using open public spaces to get together, relax or eat. In Tokyo most of the encounters happen inside of the buildings, restaurants rarely have street facing window tables or terraces. But most of all I miss the feeling of belonging that I had in Milan, where even shop keepers seem more humane and greet you in a personal manner if you're a regular customer, initiating nice little conversations everywhere in the city. Here, unless you're in special "hipster" districts (which in turn tend to be quite expensive), its almost impossible to get this feeling through the wall of immense politeness, bows and standard service behaviour.

And then remember I said Japanese people perceive time as a cyclical matter? That thing is getting on my nerves, too. It means that nobody cares how clever and productive you are, if you don't sit in the office as much time as your colleagues do - you're not worthy of any praise. Obviously, this attitude makes everyone less efficient as people just stay overtime everyday and tire themselves physically while doing less actual work and more mistakes. I've had a chance to visit a few famous architecture bureaus here and some employees admitted that sometimes before big deadlines they stay overnight for weeks because if most people stay they have no choice. However, they lose concentration and most of the time just pretend to do something productive in order to be in the same boat with the others. The importance of being always present also occasionally provokes terrible outbursts of flu since people never stay home when they're sick and pass their cold to all the colleagues. I myself became a victim of this phenomena since university functions in the same way. For most courses your grade is based on your attendance alone. That means even if you complete all assignments and understand the subject perfectly well but miss one class for any reason — you will never get a 100% as your final grade. Really, even if you're a god damn genius, incomplete attendance — forget about your A. What's the logic behind this? In Japanese way of doing things it's more important to sit through all the lectures with everyone else, otherwise it's not fair to your peers who in this way presumably spent more time studying. The worst part of this attitude is that it demotivates you to produce any kind of outstanding results as an individual. At the beginning I tried to do my best for all the courses, but gradually I lost all interest since nobody really cared about anything I did or said. And I just started to sleep during all lectures. You know what? It's considered totally normal to doze off when professor is talking and nobody bats an eye. You just have to choose the right position for your head so that you don't look too comfortable [I think I'm already becoming a pro since I also practice during commutes]. In this way it makes the professor think that you've been studying up all night and respect you more as a truly hardworking person. Ridiculous in our perspective, but in a community-based society such as Japan process seems to be more important than the result and group work (even if totally inefficient) is respected more than individual. The moral of the story: if personal self-realisation is what makes you happy, don't ever consider working in a Japanese company.

All this might sound as if I'm lonely and completely exhausted after spending just four months in this city. While it's definitely true and I'm a bit disappointed in Japan in terms of prolonged stay, I've had lots of fun and fulfilling times, really. Here's the proof:

So far I've had so many new experiences and met so many new people that I'm having trouble to grasp and process all this information. On Wednesday I'm setting out to Hokkaido on my first big backpack trip to finally meditate and digest everything. In a couple of weeks I'll hopefully publish a chapter with better quality images and more organised thoughts!

P.S. You know I've always had problems with minimising the length of my texts so thanks to everyone who read this till the end, you're awesome! Let me know what you think in personal messages, I'll be happy to hear from you.