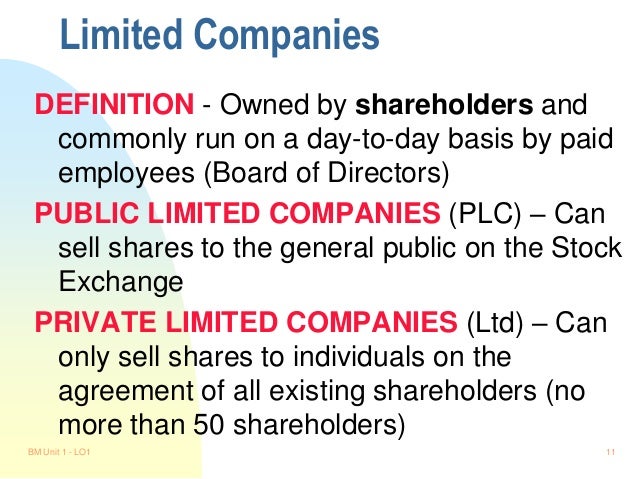

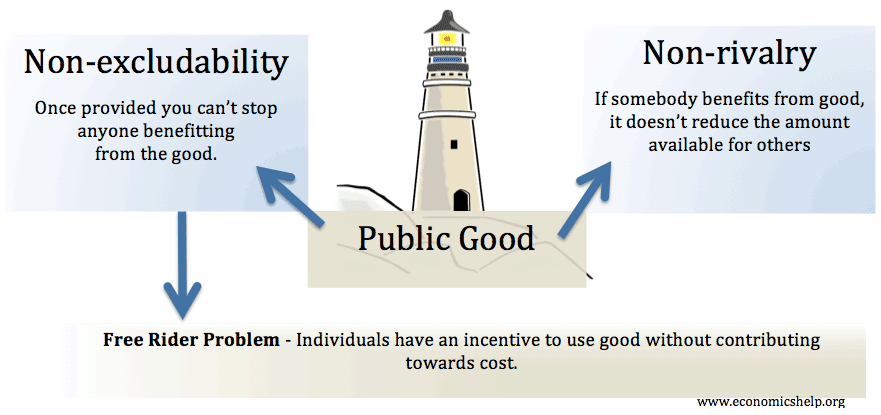

Define Private Public

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Для получения триального ключа

заполните форму ниже

Enterprise License (расширенная версия)

* Нажимая на кнопку, вы даете согласие на обработку

своих персональных данных. См. Политику конфиденциальности

** На сайте установлена reCAPTCHA и применяются

Политика конфиденциальности и Условия использования Google.

* Нажимая на кнопку, вы даете согласие на обработку

своих персональных данных. См. Политику конфиденциальности

** На сайте установлена reCAPTCHA и применяются

Политика конфиденциальности и Условия использования Google.

Суммарный объем приложенных файлов не должен превышать 20 Мб. Не получится приложить файл .exe или .i

* Нажимая на кнопку, вы даете согласие на обработку

своих персональных данных. См. Политику конфиденциальности

** На сайте установлена reCAPTCHA и применяются

Политика конфиденциальности и Условия использования Google.

Для получения лицензии для вашего открытого

проекта заполните, пожалуйста, эту форму

* Нажимая на кнопку, вы даете согласие на обработку

своих персональных данных. См. Политику конфиденциальности

** На сайте установлена reCAPTCHA и применяются

Политика конфиденциальности и Условия использования Google.

Для получения лицензии для вашего открытого

проекта заполните, пожалуйста, эту форму

* Нажимая на кнопку, вы даете согласие на обработку

своих персональных данных. См. Политику конфиденциальности

** На сайте установлена reCAPTCHA и применяются

Политика конфиденциальности и Условия использования Google.

Мне интересно попробовать плагин на:

* Нажимая на кнопку, вы даете согласие на обработку

своих персональных данных. См. Политику конфиденциальности

** На сайте установлена reCAPTCHA и применяются

Политика конфиденциальности и Условия использования Google.

Если вы так и не получили ответ, пожалуйста, проверьте папку

Spam/Junk и нажмите на письме кнопку "Не спам".

Так Вы не пропустите ответы от нашей команды.

Найдите ошибки и потенциальные уязвимости в исходном коде C, C++, C#, Java на Windows, Linux, macOS

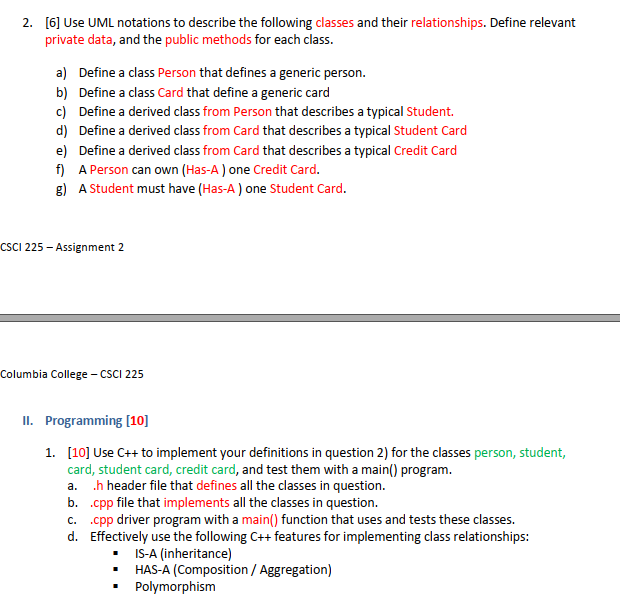

Язык C++, компиляторы и библиотеки движутся всё больше в сторону ужесточения контроля того, что пишет программист. Это хорошо. Все наверное слышали шутки вот на эту тему: #define true ((rand() % 100) < 95 ? true : false). Шутки, шутками, но возможность переопределить ключевые слова иногда приводит к значительному затруднению понимания программы или непонятным ошибкам.

В новой Visual Studio 11 сделана проверка для выявления переопределения ключевых слов. Для этого в файле xkeycheck.h имеется следующий текст:

Если вы планируете в скором будущем использовать Visual C++ 11, то можно заранее постараться исправить код, где используется переопределение ключевых слов. Чаще всего это применяется в различных тестах. Например, чтобы в тестах получить доступ к закрытым членам классов, используются следующий приём:

Теперь этот код скомпилирован не будет. Мы, например, встретили такую ошибку, при попытке собрать с помощью Visual C++ 11 исходные коды игры Doom 3 (файл TypeInfo.cpp).

Желаем вам поменьше использовать различных обманных приёмов. Они экономят время в краткосрочной перспективе, но рано или поздно всплывают при смене платформы/компилятора и их приходится переписывать.

Для получения триального ключа

заполните форму ниже:

* Нажимая на кнопку, вы даете согласие на обработку

своих персональных данных. См. Политику конфиденциальности

** На сайте установлена reCAPTCHA и применяются

Политика конфиденциальности и Условия использования Google.

Свяжитесь с нами по техническим

или другим вопросам

Свяжитесь с нами по техническим

или другим вопросам

Этот сайт использует куки и другие технологии, чтобы предоставить вам более персонализированный опыт. Продолжая просмотр страниц нашего веб-сайта, вы принимаете условия использования этих файлов. Если вы не хотите, чтобы ваши данные обрабатывались, пожалуйста, покиньте данный сайт. Подробнее →

If I remember correctly, there was a reason for it - certainly not a good one, but a reason: Some experimental test code needed to access a class member which was declared private, and the author of that code wasn't supposed to change the class under test, or did not have access to it.

This disgusting hack was probably meant as a stopgap solution, but then remained in the code for way too much time - until it was re-discovered and became a part of our local programming folklore. I was actually grateful for this hack - without it, I'd probably still be searching for a name for my blog!

And then, just a few days ago, I came across the following excerpt from the standard for the C++ standard library (ISO/IEC 14882:1998(E), section 17.4.3.1.1):

Good heavens, my blog is cursed upon by the standard! Expelled will I be from the C++ community! Never will I be on a first-name basis with Mr. Stroustrup! What have I done...

The other day, I battled global variables in Lisp by using this construct:

globalFoo is neither declared nor bound within the functions foobar1 or foobar2; it is a free variable. When Lisp encounters such a variable, it will search the enclosing code (the lexical environment) for a binding of the variable; in the above case, it will find the binding established by the let statement, and all is peachy.

globalFoo's scope is limited to the functions foobar1 and foobar2; functions outside of the let statement cannot refer to the variable. But we can call foobar1 and foobar2 even after returning from the let statement, and thereby read or modify globalFoo without causing a runtime errors.

Lisp accomplishes this by creating objects called closures. A closure is a function plus a set of bindings of free variables in the function. For instance, the function foobar1 plus the binding of globalFoo to a place in memory which stores "42" is such a closure.

Hmmm - what does this remind you of? We've got a variable which is shared between two functions, and only those functions have access to the variable, while outside callers have not... he who has never tried to encapsulate data in an object shall cast the first pointer!

So this is how closures might remind us of objects. But let's look at it from a different angle now - how would we implement closures in conventional languages?

Imagine that while we invoke a function, we'd keep its parameters and local variables on the heap rather than on the stack, so instead of stack frames we maintain heap frames. You could then think of a closure as:

Because the "stack" frames are actually kept on the heap and we are therefore no longer obliged to follow the strict rules of the hardware stack, the contents of those frames can continue to live even beyond the scope of the executed function.

So we're actually storing a (partial) snapshot of the execution context of a function, along with the code of the function!

Let's see how we could implement this. The first obvious first-order approximation is in C++; it's a function object. A function object encapsulates a function pointer and maybe also copies of parameters needed for the function call:

FunctionObject captures a snapshot of a function call with its parameters. This is useful in a number of situations, as can be witnessed by trying to enumerate the many approaches to implement something like this in C++ libraries such as Boost; however, this is not a closure. We're "binding" function parameters in the function object - but those are, in the sense described earlier, not free variables anyway. On the other hand, if the code of the function referred to by the FunctionObject had any free variables, the FunctionObject wouldn't be able to bind them. So this approach won't cut it.

There are other approaches in C++, of course. For example, I recently found the Boost Lambda Library which covers at least parts of what I'm after. At first sight, however, I'm not too sure its syntax is for me. I also hear that GCC implements nested functions:

Unfortunately, extensions like this didn't make it into the standards so far. So let's move on to greener pastures. Next stop: How anonymous delegates in C# 2.0 implement closures.

When asked for a TWiki account, use your own or the default TWikiGuest account.

In Lisp, you usually declare a global variable using defvar and defparameter - but this way, the variable not only becomes global, but also special. They are probably called special because of the special effects that they display - see my blog entry for an idea of the confusion this caused to a simple-minded C++ programmer (me).

Most of the time, I would use defvar to emulate the effect of a "file-global" static variable in C++, and fortunately, this can be implemented in a much cleaner fashion using a let statement at the right spot. Example:

The let statement establishes a binding for globalFoo which is only accessible within foobar1 and foobar2. This is even better than a static global variable in C++ at file level, because this way precisely the functions which actually have a business with globalFoo are able to use it; the functions foobar1 and foobar2 now share a variable. We don't have to declare a global variable anymore and thereby achieve better encapsulation and at the same time avoid special variables with their amusing special effects. Life is good!

This introduces another interesting concept in Lisp: Closures, i.e. functions with references to variables in their lexical context. More on this hopefully soon.

When asked for a TWiki account, use your own or the default TWikiGuest account.

While learning Lisp, bindings and closures were particularly strange to me. It took me way too long until I finally grokked lexical and dynamic binding in Lisp. Or at least I think I get it now.

Let us consider the following C code:

A seasoned C or C++ programmer will parse this code with his eyes shut and tell you immediately that quelle_surprise will print "42" because shatter_illusions() refers to the global definition of fortytwo.

Meanwhile, back in the parentheses jungle:

To a C++ programmer, this looks like a verbatim transformation of the code above into Lisp syntax, and he will therefore assume that the code will still answer "42". But it doesn't: quelle-surprise thinks the right answer is "4711"!

Subtleties aside, the value of Lisp variables with lexical binding is determined by the lexical structure of the code, i.e. how forms are nested in each other. Most of the time, let is used to establish a lexical binding for a variable.

Variables which are dynamically bound lead a more interesting life: Their value is also determined by how forms call each other at runtime. The defvar statement above both binds fortytwo to a value of 42 and declares the variable as dynamic or special, i.e. as a variable with dynamic binding. Even if code is executed which usually would bind the variable lexically, such as a let form, the variable will in fact retain its dynamic binding.

Kyoto Common Lisp defines defvar as follows:

In the highlighted form, the variable name is declared as special, which is equivalent with dynamic binding in Lisp.

This effect is quite surprising for a C++ programmer. I work with both Lisp and C++, switching back and forth several times a day, so I try to minimize the number of surprises a much as I can. Hence, I usually stay away from special/dynamic Lisp variables, i.e. I tend to avoid defvar and friends and only use them where they are really required.

Unfortunately, defvar and defparameter are often recommended in Lisp tutorials to declare global variables. Even in these enlightened times, there's still an occasional need for a global variable, and if you follow the usual examples out there, you'll be tempted to quickly add a defvar to get the job done. Except that now you've got a dynamically bound variable without even really knowing it, and if you expected this variable to behave like a global variable in C++, you're in for a surprise:

So you call shatter-illusions once through quelle-surprise, and it tells you that the value of the variable fortytwo, which is supposedly global, is 4711. And then you call the same function again, only directly, and it will tell you that this time fortytwo is 42.

The above code violates a very useful convention in Lisp programming which suggests to mark global variables with asterisks (*fortytwo*). This, along with the guideline that global variables should only be modified using setq and setf rather than let, will avoid most puzzling situations like the above. Still, I have been confused by the dynamic "side-effect" of global variables declared by defvar often enough now that I made it a habit to question any defvar declarations I see in Lisp code.

More on avoiding global dynamic variables next time.

When asked for a TWiki account, use your own or the default TWikiGuest account.

The other day, I was testing COM clients which accessed a collection class via a COM-style enumerator (IEnumVARIANT). And those clients crashed as soon as they tried to do anything with the enumerator. Of course, the same code had worked just fine all the time before. What changed?

In COM, a collection interface often implements a function called GetEnumerator() which returns the actual enumerator interface (IEnumVARIANT), or rather, a pointer to the interface. In my case, the signature of that function was:

Didn't I say that GetEnumerator is supposed to return an IEnumVARIANT pointer? Yup, but for reasons which I may cover here in one of my next bonus lives, that signature was changed from IEnumVARIANT to IUnknown. This, however, is merely a syntactic change - the function actually still returned IEnumVARIANT pointers, so this alone didn't explain the crashes.

Well, I had been bitten before by smart pointers, and it happened again this time! The COM client code declared a smart pointer for the enumerator like this:

This is perfectly correct code as far as I can tell, but it causes a fatal avalanche:

Any subsequent attempt to access the interface through the smart pointer now crashes because the smart pointer tries to use its internal interface pointer - which is 0.

All this happens without a single compiler or runtime warning. Now, of course it was our own silly fault - the GetEnumerator declaration was bogus. But neither C++ nor ATL really helped to spot this issue. On the contrary, the C++ type system (and its implicit type conversions) and the design of the ATL smart pointer classes collaborated to hide the issue away from me until it was too late.

When asked for a TWiki account, use your own or the default TWikiGuest account.

A few days ago, I dissed good ol' aCC on the HP-UX platform, but for political correctness, here's an amusing quirk in Microsoft's compiler as well. Consider the following code:

The C++ compiler which ships with VS.NET 2003 is quite impressed with those two lines:

What the compiler really wants to tell me is that it does not want me to redefine gazonk. The C++ compiler in VS 2005 gets this right.

If you refer back to the previous blog entry, you'll find that it took me only one line to crash aCC on HP-UX. It took two lines in the above example to crash Microsoft's compiler. Hence, I conclude that their compiler is only half as bad as the HP-UX compiler.

If you want to argue with my reasoning, let me tell you that out there in the wild, I have rarely seen a platform-vs-platform discussion based on facts which were any better than that. Ahem...

When asked for a TWiki account, use your own or the default TWikiGuest account.

After fixing a nasty bug today, I let off some steam by surfing the 'net for fun stuff and new developments. For instance, Bjarne Stroustrup recently reported on the plans for C++0x. I like most of the stuff he presents, but still was left disturbingly unimpressed with it. Maybe it's just a sign of age, but somehow I am not really thrilled anymore by a programming language standard scheduled for 2008 which, for the first time in the history of the language, includes something as basic as a hashtable.

Yes, I know that pretty much all the major STL implementations already have hashtable equivalents, so it's not a real issue in practice. And yes, there are other very interesting concepts in the standard which make a lot of sense. Still - I used to be a C++ bigot, but I feel the zeal is wearing off; is that love affair over?

Confused and bewildered, I surf some other direction, but only to have Sriram Krishnan explain to me that Lisp is sin. Oh great. I happen to like Lisp a lot - do I really deserve another slap in the face on the same day?

But Sriram doesn't really flame us Lisp geeks; quite to the contrary. He is a programmer at Microsoft and obviously strongly impressed by Lisp as a language. His blog entry illustrates how Lisp influenced recent developments in C# - and looks at reasons why Lisp isn't as successful as many people think it should be.

Meanwhile, back in the C++ jungle: Those concepts are actually quite clever, and solve an important problem in using C++ templates.

In a way, C++ templates use what elsewhere is called duck typing. Why do I say this? Because the types passed to a template are checked implicitly by the template implementation rather than its declaration. If the template implementation says f = 0 and f is a template parameter, then the template assumes that f provides an assignment operator - otherwise the code simply won't compile. (The difference to duck typing in its original sense is that we're talking about compile-time checks here, not dynamic function call resolution at run-time.)

Hence, templates do not require types to derive from certain classes or interfaces, which is particularly important when using templates for primitive types (such as int or float). However, when the type check fails, you'll drown in error messages which are cryptic enough to violate the Geneva convention. To fix the error, the user of a template often has to inspect the implementation of the template to understand what's going on. Not exactly what they call encapsulation.

Generics in .NET improve on this by specifying constraints explicitly:

T is required to implement IFunny. If it doesn't, the compiler will tell you that T ain't funny at all, and that's that. No need to dig into the implementation details of the generic function.

C++ concepts extend this idea: You can specify pretty arbitrary restrictions on the type. An example from Stroustrup's and Dos Reis' paper:

So if T and U fit into the Assignable concept, the compiler will accept them as parameters of the template. This is cute: In true C++ tradition, this provides maximum flexibility and performance, but solves the original problem.

Still, that C# code is much easier on the eye...

When asked for a TWiki account, use your own or the default TWikiGuest account.

The following C++ code will be rejected by both Visual C++ and gcc:

gcc says something like "error: member `BOX ::box' with constructor not allowed in union"; Visual C++ reports a compiler error C2620.

Now that is

Sex Adventure Between Patient And Doctor

Pussy Licking Teen Lesbians

Kannada Incest Sex Stories

Xxx Foto Paula Shy

Teen Babies Com

define-private-public (Benjamin Summerton) · GitHub

Прощай #define private public

#define private public - Claus Brod on C++

define-private-public’s gists · GitHub

Don't use `define private public` in test files · Issue ...

A Simple HTTP server in C# · GitHub

#define private public_Hello world!-CSDN博客

How to Change Network from Public to Private in Windows 10

Define Private Public