DJ’s Homeless Mommy

@americanwords

There was no guarantee that doing an open adoption would get us a baby any faster than doing a closed or foreign adoption. In fact, our agency warned us that, as a gay male couple, we might be in for a long wait. This point was driven home when both birth mothers who spoke at the two-day open adoption seminar we were required to attend said that finding “good, Christian homes” for their babies was their first concern.

But we decided to go ahead and try to do an open adoption anyway. If we became parents, we wanted our child’s biological parents to be a part of his life.

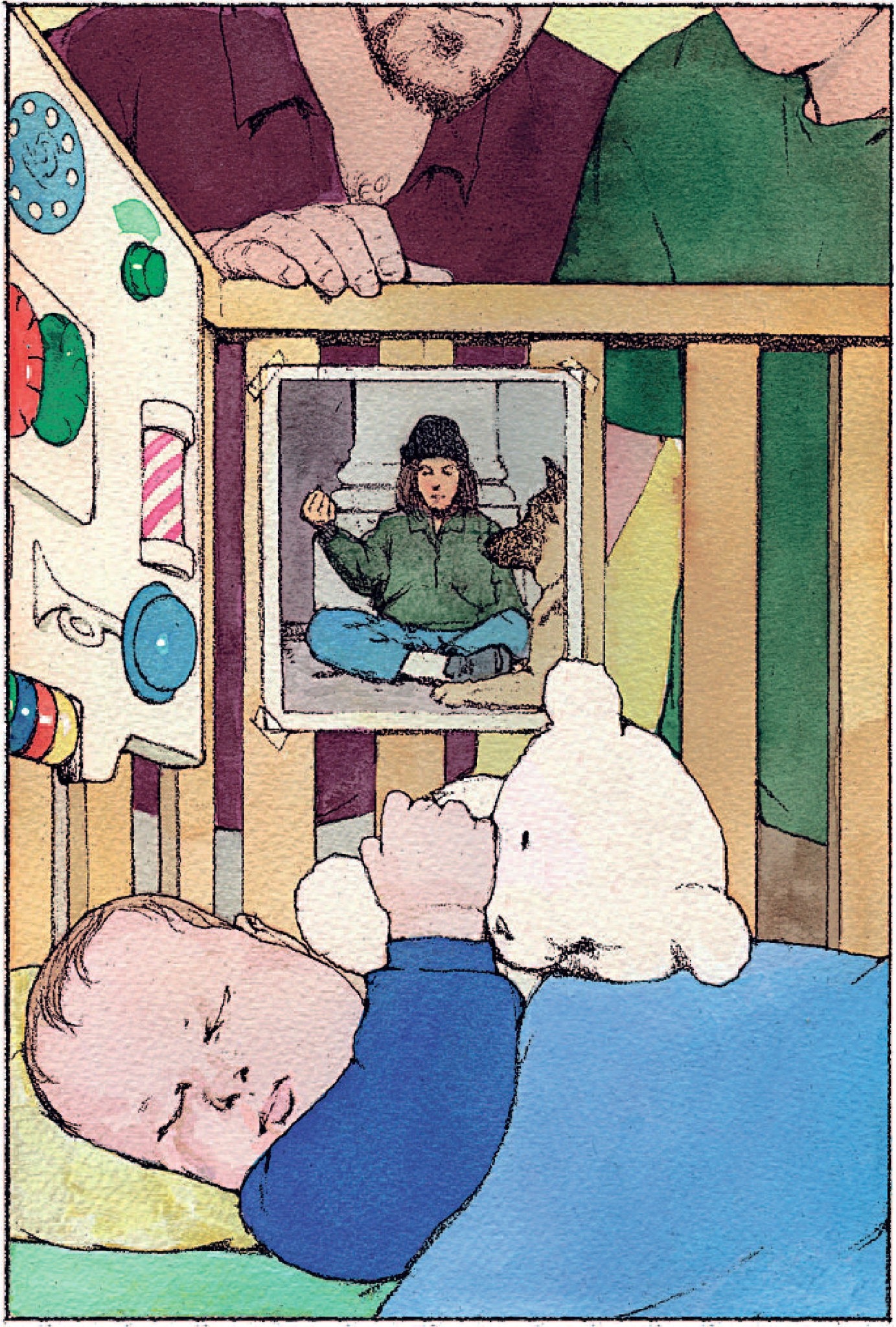

As it turns out we didn’t have to wait long. A few weeks after our paperwork was done, we got a call from the agency. A 19-year-old homeless street kid — homeless by choice and seven months pregnant by accident — had selected us from the agency’s pool of screened parent wannabes. The day we met her the agency suggested all three of us go out for lunch — well, four of us if you count Wish, her German shepherd, five if you count the baby she was carrying.

We were bursting with touchy-feely questions, but she was wary, only interested in the facts: she knew who the father was but not where he was, and she couldn’t bring up her baby on the streets by herself. That left adoption. And she was willing to jump through the agency’s hoops — which included weekly counseling sessions and a few meetings with us — because she wanted to do an open adoption, too.

We were with her when DJ was born. And we were in her hospital room two days later when it was time for her to give him up. Before we could take DJ home we literally had to take him from his mother’s arms as she sat sobbing in her bed.

I was 33 when we adopted DJ, and I thought I knew what a broken heart looked like, how it felt, but I didn’t know anything. You know what a broken heart looks like? Like a sobbing teenager handing over a two-day-old infant she can’t take care of to a couple she hopes can.

Ask a couple hoping to adopt what they want most in the world, and they’ll tell you there’s only one thing on earth they want: a healthy baby. But many couples want something more. They want their child’s biological parents to disappear so there will never be any question about who their child’s “real” parents are. The biological parents showing up on their doorstep, lawyers in tow, demanding their kid back is the nightmare of all adoptive parents, endlessly discussed in adoption chat rooms and during adoption seminars.

But it seemed to us that all adopted kids eventually want to know why they were adopted, and sooner or later they start asking questions. “Didn’t they love me?” “Why did they throw me away?” In cases of closed adoptions there’s not a lot the adoptive parents can say. Fact is, they don’t know the answers. We did.

Like most homeless street kids, our son’s mother works a national circuit. Portland or Seattle in the summer. Denver, Minneapolis, Chicago and New York in the late summer and early fall. Phoenix, Las Vegas or Los Angeles in the winter and spring. Then she hitchhikes or rides the rails back up to Portland, where she’s from, and starts all over again.

For the first few years after we adopted DJ his mother made a point of coming up to Seattle during the summer so we could get together. When she wasn’t in Seattle she kept in touch by phone. Her calls were usually short. She would ask how we were, we’d ask her the same, then we’d put DJ on the phone. She didn’t gush. He didn’t know what to say. But it was important to DJ that his mother called.

When DJ was 3, his mother stopped calling regularly and visiting. When she did call, it was usually with disturbing news. One time her boyfriend died of alcohol poisoning. They were sleeping on a sidewalk in New Orleans, and when she woke up he was dead. Another time she called after her next boyfriend started using heroin again. Soon the calls stopped, and we began to worry about whether she was alive or dead. After six months with no contact I started calling hospitals. Then morgues.

When DJ’s fourth birthday came and went without a call, I was convinced that something had happened to her on the road or in a train yard somewhere. She had to be dead.

I was tearing down the wallpaper in an extra bedroom one night shortly after DJ turned 4. His best friend, a boy named Haven, had spent the night, and after Haven’s mother picked him up, DJ dragged a chair into the room and watched as I pulled wallpaper down in strips.

“Haven has a mommy,” he suddenly said, “and I have a mommy.”

“That’s right,” I responded.

He went on: “I came out of my mommy’s tummy. I play with my mommy in the park.” Then he looked at me and asked, “When will I see my mommy again?”

“This summer,” I said, hoping it wasn’t a lie. It was April, and we hadn’t heard from DJ’s mother since September. “We’ll see her in the park, just like last summer.”

We didn’t see her in the summer. Or in the fall or spring. I wasn’t sure what to tell DJ. We knew that she hadn’t thrown him away and that she loved him. We also knew that she wasn’t calling and could be dead. I was convinced she was dead. But dead or alive, we weren’t sure how to handle the issue with DJ. Which two-by-four to hit him with? That his mother was in all likelihood dead? Or that she was out there somewhere but didn’t care enough to come by or call?

And soon he would be asking more complicated questions. What if he wanted to know why his mother didn’t love him enough to take care of herself? So she could live long enough to be there for him? So she could tell him herself how much she loved him when he was old enough to remember her and to know what love means?

My partner and I discussed these issues late at night when DJ was in bed, thankful for each day that passed without having the issue of his missing mother come up. We knew we wouldn’t be able to avoid or finesse it after another summer arrived in Seattle. As the weeks ticked away, we admitted that those closed adoptions we’d frowned upon were starting to look pretty good. Instead of being a mystery his mother was a mass of distressing specifics. And instead of dealing with his birth parents’ specifics at, say, 18 or 21, as many adopted children do, he would have to deal with them at 4 or 5.

HE was already beginning to deal with them. The last time she visited, when DJ was 3, he wanted to know why his mother smelled so terrible. We were taken aback and answered without thinking it through. We explained that since she doesn’t have a home she isn’t able to bathe often or wash her clothes.

We realized we screwed up even before DJ started to freak. What could be more terrifying to a child than the idea of not having a home? Telling him that his mother chose to live on the streets, that for her the streets were home, didn’t cut it. For months DJ insisted that his mother was just going to have to come live with us. We had a bathroom, a washing machine. She could sleep in the guest bedroom. When grandma came to visit, she could sleep in his bed and he would sleep on the floor.

We did hear from DJ’s mother again, 14 months after she disappeared, when she called from Portland. She wasn’t dead. She’d lost track of time and didn’t make it up to Seattle before it got too cold and wet. And whenever she thought about calling, it was too late or she was too drunk. When she told me she’d reached the point where she got sick when she didn’t drink, I gently suggested that maybe it was time to get off the streets, stop drinking and using drugs and think about her future. I could hear her rolling her eyes.

She’d chosen us over all the straight couples, she said, because we didn’t look old enough to be her parents. She didn’t want us to start acting like her parents now. She would get off the streets when she was ready. She wasn’t angry and didn’t raise her voice. She just wanted to make sure we understood each other.

DJ was happy to hear from his mother, and the 14 months without a call or a visit were forgotten. We went down to Portland to see her, she apologized to DJ in person, we took some pictures, and she promised not to disappear again.

We didn’t hear from her for another year. This time when she called she wasn’t drunk. She was in prison, charged with assault. She’d been in prison before for short stretches, picked up on vagrancy and trespassing charges. But this time was different. She needed our help. Or her dog did.

Her boyfriends and traveling companions were always vanishing, but her dog, Wish, was the one constant presence in her life. Having a large dog complicates hitchhiking and hopping trains, but DJ’s mother is a petite woman, and her dog offers her protection. And love.

Late one night in New Orleans, she told us from a noisy common room in the jail, she got into an argument with another homeless person. He lunged at her, and Wish bit him. She was calling, she said, because it didn’t look as if she would get out of prison before the pound put Wish down. She was distraught. We had to help her save Wish, she begged. She was crying, the first time I’d heard her cry since that day in the hospital six years before.

Five weeks and $1,600 later, we had managed not only to save Wish but also to get DJ’s mother out and the charges dropped. When we talked on the phone, I urged her to move on to someplace else. I found out three months later that she’d taken my advice. She was calling from a jail in Virginia, where she’d been arrested for trespassing at a train yard. She was calling to say hello to DJ.

I’ve heard people say that choosing to live on the streets is a kind of slow-motion suicide. Having known DJ’s mother for seven years now, I’d say that’s accurate. Everything she does seems to court danger. I’ve lost track of the number of her friends and boyfriends who have died of overdoses, alcohol poisoning and hypothermia.

As DJ gets older, he is getting a more accurate picture of his mother, but so far it doesn’t seem to be an issue for him. He loves her. A photo of a family reunion we attended isn’t complete, he insisted, because his mother wasn’t in it. He wants to see her “even if she smells,” he said. We’re looking forward to seeing her, too. But I’m tired.

NOW for the may-God-rip-off-my-fingers-before-I-type-this part of the essay: I’m starting to get anxious for this slo-mo suicide to end, whatever that end looks like. I’d prefer that it end with DJ’s mother off the streets in an apartment somewhere, pulling her life together. But as she gets older that resolution is getting harder to picture.

A lot of people who self-destruct don’t think twice about destroying their children in the process. Maybe DJ’s mother knew she was going to self-destruct and wanted to make sure her child wouldn’t get hurt. She left him somewhere safe, with parents she chose for him, even though it broke her heart to give him away, because she knew that if he were close, she would hurt him, too.

Sometimes I wonder if this answer will be good enough for DJ when he asks us why his mother couldn’t hold it together just enough to stay in the world for him. I kind of doubt it.