Computing the UTF-8 size of a Latin 1 string quickly (ARM NE…

Daniel Lemire's blogWhile most of our software relies on Unicode strings, we often still encounter legacy encodings such as Latin 1. Before we convert Latin 1 strings to Unicode (e.g., UTF-8), we must compute the size of the UTF-8 string. It is fairly easy: all ASCII characters map 1 byte to 1 byte, while other characters (with code point values from 128 to 256) map 1 Latin byte to 2 Unicode bytes (in UTF-8).

Computers represent strings using bytes. Most often, we use the Unicode standard to represent characters in bytes. The universal format to exchange strings online is called UTF-8. It can represent over a million characters while retaining compatibility with the ancient ASCII format.

Though most of our software stack has moved to Unicode strings, there are still older standards like Latin 1 used for European strings. Thus we often need to convert Latin 1 strings to UTF-8. It is useful to first compute the size (in bytes) of the eventual UTF-8 strings. You can code a simple C function to compute the UTF-8 size from the Latin 1 input as follow:

size_t scalar_utf8_length(const char * c, size_t len) {

size_t answer = 0;

for(size_t i = 0; i<len; i++) {

if((c[i]>>7)) { answer++;}

}

return answer + len;

}

In Computing the UTF-8 size of a Latin 1 string quickly (AVX edition), I reviewed faster techniques to solve this problem on x64 processors.

What about ARM processors (as in your recent MacBook)?

Keyhan Vakil came up with a nice solution with relies on the availability for “narrowing instructions” in ARM processors. Basically you can take a 16-byte vector registers and create a 8-byte register (virtually) by truncating or rounding the results. Conveniently, you can also combine bit shifting with narrowing.

Consider pairs of successive 8-bit words as a 16-bit word. If you shift the result by 4 bits and then keep only the least significant 8 bits of the result, then the most significant 4 bits from the second 8-bit word become the least significant 4 bits in the result while the least significant 4 bits from the first 8-bit word become the most significant 4 bits.you can shift the 16-bit. E.g., if the 16 bits start out as aaaaaaaabbbbbbbb then the shift-by-four-and-narrow creates the byte value aaaabbbb.

This is convenient because vectorized comparison functions often generate filled bytes when the comparison is true (all 1s). The final algorithm in C looks as follows:

uint64_t utf8_length_kvakil(const uint8_t *data, uint32_t length) {

uint64_t result = 0;

const int lanes = sizeof(uint8x16_t);

uint8_t rem = length % lanes;

const uint8_t *simd_end = data + (length / lanes) * lanes;

const uint8x16_t threshold = vdupq_n_u8(0x80);

for (; data < simd_end; data += lanes) {

// load 16 bits

uint8x16_t input = vld1q_u8(data);

// compare to threshold (0x80)

uint8x16_t withhighbit = vcgeq_u8(input, threshold);

// shift and narrow

uint8x8_t highbits = vshrn_n_u16(vreinterpretq_u16_u8(withhighbit), 4);

// we have 0, 4 or 8 bits per byte

uint8x8_t bitsperbyte = vcnt_u8(highbits);

// sum the bytes vertically to uint16_t

result += vaddlv_u8(bitsperbyte);

}

result /= 4; // we overcounted by a factor of 4

// scalar tail

for (uint8_t j = 0; j < rem; j++) {

result += (simd_end[j] >> 7);

}

return result + length;

}

Is it fast?

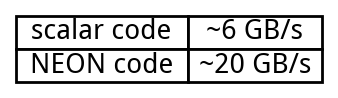

On my Apple M2, it is three times as fast as what the compiler produces from the scalar code on large enough inputs. Observe that the compiler already relies on vector instructions.

My source code is available. Your results will vary.

Can you beat Vakil? You can surely reduce the instruction count but once you reach speeds like 20 GB/s, it becomes difficult to go much faster without hitting memory and cache speed limits.

Generated by RSStT. The copyright belongs to the original author.