Cockwork Orange

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

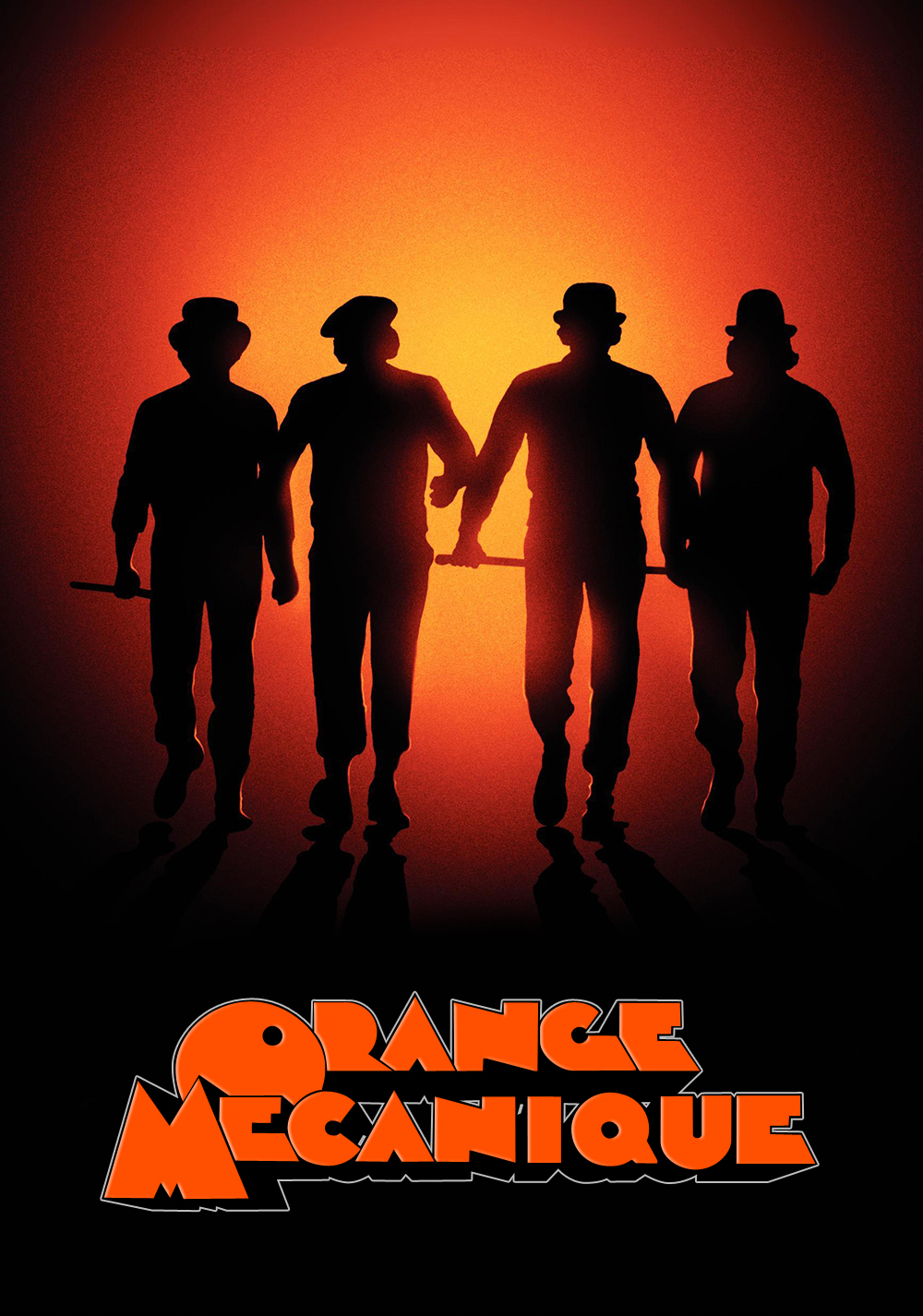

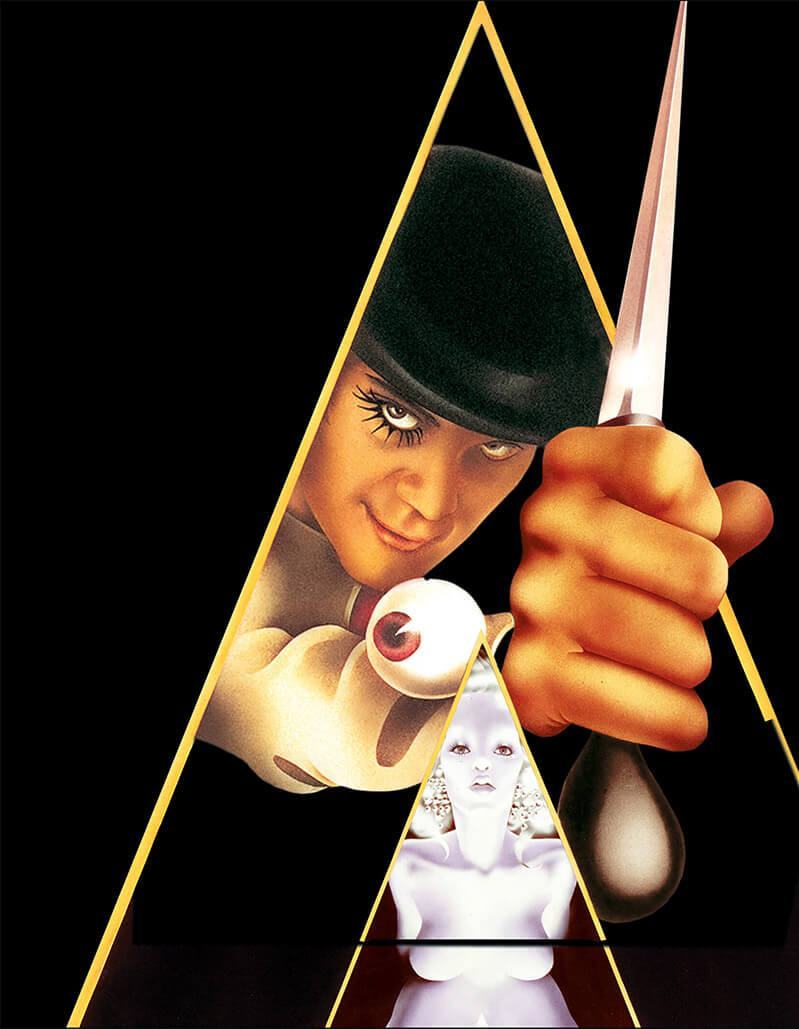

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold

Warner Bros. (US)

Columbia-Warner Distributors (UK)

19 December 1971 (New York City)

13 January 1972 (United Kingdom[1])

2 February 1972 (United States)

A Clockwork Orange is a 1971 dystopian crime film adapted, produced, and directed by Stanley Kubrick, based on Anthony Burgess's 1962 novel of the same name. It employs disturbing, violent images to comment on psychiatry, juvenile delinquency, youth gangs, and other social, political, and economic subjects in a dystopian near-future Britain.

Alex (Malcolm McDowell), the central character, is a charismatic, antisocial delinquent whose interests include classical music (especially Beethoven), committing rape, theft and what is termed "ultra-violence". He leads a small gang of thugs, Pete (Michael Tarn), Georgie (James Marcus), and Dim (Warren Clarke), whom he calls his droogs (from the Russian word друг, "friend", "buddy"). The film chronicles the horrific crime spree of his gang, his capture, and attempted rehabilitation via an experimental psychological conditioning technique (the "Ludovico Technique") promoted by the Minister of the Interior (Anthony Sharp). Alex narrates most of the film in Nadsat, a fractured adolescent slang composed of Slavic (especially Russian), English, and Cockney rhyming slang.

The film premiered in New York City on 19 December 1971 and was released in the United Kingdom on 13 January 1972. The film was met with polarised reviews from critics, and was also heavily controversial due to its depictions of graphic violence. It was later withdrawn from British cinemas at Kubrick's behest, and was also banned in several other countries. In the years following, the film underwent a critical re-evaluation and gained a cult following. It received several awards and nominations, including four nominations at the 44th Academy Awards. In 2020, the film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

In a futuristic Britain, Alex DeLarge is the leader of a gang of "droogs": Georgie, Dim and Pete. One night, after getting intoxicated on drug-laden "milk-plus", they engage in an evening of "ultra-violence", which includes a fight with a rival gang. They drive to the country home of writer Frank Alexander and trick his wife into letting them inside. They beat Alexander to the point of crippling him, and Alex rapes Alexander's wife while singing "Singin' in the Rain". The next day, while truant from school, Alex is approached by his probation officer, PR Deltoid, who is aware of Alex's activities and cautions him.

Alex's droogs express discontent with petty crime and want more equality and high-yield thefts, but Alex asserts his authority by attacking them. Later, Alex invades the home of a wealthy "cat-lady" and bludgeons her with a phallic sculpture while his droogs remain outside. On hearing sirens, Alex tries to flee but Dim smashes a bottle in his face, stunning Alex and leaving him to be arrested. With Alex in custody, Deltoid gloats that the cat-lady died, making Alex a murderer. He is sentenced to fourteen years in prison.

Two years into the sentence, Alex eagerly takes up an offer to be a test subject for the Minister of the Interior's new Ludovico technique, an experimental aversion therapy for rehabilitating criminals within two weeks. Alex is strapped to a chair, his eyes are clamped open and he is injected with drugs. He is then forced to watch films of sex and violence, some of which are accompanied by the music of his favourite composer, Ludwig van Beethoven. Alex becomes nauseated by the films and, fearing the technique will make him sick upon hearing Beethoven, begs for an end to the treatment.

Two weeks later, the Minister demonstrates Alex's rehabilitation to a gathering of officials. Alex is unable to fight back against an actor who taunts and attacks him and becomes ill wanting sex with a topless woman. The prison chaplain complains that Alex has been robbed of his free will; however, the Minister asserts that the Ludovico technique will cut crime and alleviate crowding in prisons.

Alex is released from jail, only to find that the police have sold his possessions as compensation to his victims and his parents have let out his room. Alex encounters an elderly vagrant whom he attacked years earlier, and the vagrant and his friends attack him. Alex is saved by two policemen but is shocked to find they are his former droogs Dim and Georgie. They drive him to the countryside, beat him up, and nearly drown him before abandoning him. Alex barely makes it to the doorstep of a nearby home before collapsing.

Alex wakes up to find himself in the home of Mr Alexander, who is now confined to a wheelchair. Alexander does not recognise Alex from the previous attack but knows of Alex and the Ludovico technique from the newspapers. He sees Alex as a political weapon and prepares to present him to his colleagues. While bathing, Alex breaks into "Singin' in the Rain", causing Alexander to realise that Alex was the person who assaulted his wife and him. With help from his colleagues, Alexander drugs Alex and locks him in an upstairs bedroom. He then plays Beethoven's Ninth Symphony loudly from the floor below. Unable to withstand the sickening pain, Alex attempts suicide by jumping out the window.

Alex wakes up in a hospital with broken bones. While being given a series of psychological tests, he finds that he no longer has aversions to violence and sex. The Minister arrives and apologises to Alex. He offers to take care of Alex and get him a job in return for his co-operation with his election campaign and public relations counter offensive. As a sign of good will, the Minister brings in a stereo system playing Beethoven's Ninth. Alex then contemplates violence and has vivid thoughts of having sex with a woman in front of an approving crowd, and thinks to himself, "I was cured, all right!"

Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge

Patrick Magee as Mr Frank Alexander

Michael Bates as Chief Guard Barnes

Warren Clarke as Dim

John Clive as Stage Actor

Adrienne Corri as Mrs Mary Alexander

Carl Duering as Dr Brodsky

Paul Farrell as Tramp

Clive Francis as Joe the Lodger

Michael Gover as Prison Governor

Miriam Karlin as Catlady

James Marcus as Georgie

Aubrey Morris as P. R. Deltoid

Godfrey Quigley as Prison Chaplain

Sheila Raynor as Mum

Madge Ryan as Dr Branom

Anthony Sharp as Frederick, Minister of the Interior

Philip Stone as Dad

Michael Tarn as Pete

David Prowse as Julian

Carol Drinkwater as Nurse Feeley

Steven Berkoff as Det. Const. Tom

Margaret Tyzack as Conspirator Rubinstein

The film's central moral question (as in many of Burgess's novels) is the definition of "goodness" and whether it makes sense to use aversion therapy to stop immoral behaviour.[5] Stanley Kubrick, writing in Saturday Review, described the film as:

A social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioural psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government to use to impose vast controls on its citizens and turn them into little more than robots.[6]

Similarly, on the film production's call sheet (cited at greater length above), Kubrick wrote:

It is a story of the dubious redemption of a teenage delinquent by condition-reflex therapy. It is, at the same time, a running lecture on free-will.

After aversion therapy, Alex behaves like a good member of society, though not through choice. His goodness is involuntary; he has become the titular clockwork orange—organic on the outside, mechanical on the inside. After Alex has undergone the Ludovico technique, the chaplain criticises his new attitude as false, arguing that true goodness must come from within. This leads to the theme of abusing liberties—personal, governmental, civil—by Alex, with two conflicting political forces, the Government and the Dissidents, both manipulating Alex purely for their own political ends.[7] The story portrays the "conservative" and "liberal" parties as equally worthy of criticism: the writer Frank Alexander, a victim of Alex and his gang, wants revenge against Alex and sees him as a means of definitively turning the populace against the incumbent government and its new regime. Mr Alexander fears the new government; in a telephone conversation, he says:

Recruiting brutal young roughs into the police; proposing debilitating and will-sapping techniques of conditioning. Oh, we've seen it all before in other countries; the thin end of the wedge! Before we know where we are, we shall have the full apparatus of totalitarianism.

On the other side, the Minister of the Interior (the Government) jails Mr Alexander (the Dissident Intellectual) on the excuse of his endangering Alex (the People), rather than the government's totalitarian regime (described by Mr Alexander). It is unclear whether or not he has been harmed; however, the Minister tells Alex that the writer has been denied the ability to write and produce "subversive" material that is critical of the incumbent government and meant to provoke political unrest.

Another target of criticism is the behaviourism or "behavioural psychology" propounded by psychologists John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner. Burgess disapproved of behaviourism, calling Skinner's book Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971) "one of the most dangerous books ever written". Although behaviourism's limitations were conceded by its principal founder, Watson, Skinner argued that behaviour modification—specifically, operant conditioning (learned behaviours via systematic reward-and-punishment techniques) rather than the "classical" Watsonian conditioning—is the key to an ideal society. The film's Ludovico technique is widely perceived as a parody of aversion therapy, which is a form of classical conditioning.[8]

Author Paul Duncan said of Alex: "Alex is the narrator so we see everything from his point of view, including his mental images. The implication is that all of the images, both real and imagined, are part of Alex's fantasies".[9] Psychiatrist Aaron Stern, the former head of the MPAA rating board, believed that Alex represents man in his natural state, the unconscious mind. Alex becomes "civilised" after receiving his Ludovico "cure" and the sickness in the aftermath Stern considered to be the "neurosis imposed by society".[10] Kubrick told film critics Philip Strick and Penelope Houston that he believed Alex "makes no attempt to deceive himself or the audience as to his total corruption or wickedness. He is the very personification of evil. On the other hand, he has winning qualities: his total candour, his wit, his intelligence and his energy; these are attractive qualities and ones, which I might add, which he shares with Richard III".[11]

Anthony Burgess sold the film rights of his novel for $500, shortly after its publication in 1962.[12] Originally, the film was projected to star the rock band The Rolling Stones, with the band's lead singer Mick Jagger expressing interest in playing the lead role of Alex, and British filmmaker Ken Russell attached to direct.[12] However, this never came to fruition due to problems with the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), and the rights ultimately fell to Kubrick.[12]

McDowell was chosen for the role of Alex after Kubrick saw him in the film if.... (1968). He also helped Kubrick on the uniform of Alex's gang, when he showed Kubrick the cricket whites he had. Kubrick asked him to put the box (jockstrap) not under but on top of the costume.[13][14]

During the filming of the Ludovico technique scene, McDowell scratched a cornea,[15] and was temporarily blinded. The doctor standing next to him in the scene, dropping saline solution into Alex's forced-open eyes, was a real physician present to prevent the actor's eyes from drying. McDowell also cracked some ribs filming the humiliation stage show.[16] A unique special effect technique was used when Alex jumps out of the window in an attempt to commit suicide and the viewer sees the ground approaching the camera until collision, i.e., as if from Alex's point of view. This effect was achieved by dropping a Newman-Sinclair clockwork camera in a box, lens-first, from the third storey of the Corus Hotel. To Kubrick's surprise, the camera survived six takes.[17]

On 24 February 1971, the last day of shooting, Progress Report No. 113 has a summary of all the footage shot to date: 39,880 feet wasted, 377,090 feet exposed, 13,120 feet remain as short ends with a total of 452,960 feet used. Sound: 225,880 feet printed from 288 1/4" reel to reel tapes.

The cinematic adaptation of A Clockwork Orange (1962) was not initially planned. Screenplay writer Terry Southern gave Kubrick a copy of the novel, but, as he was developing a Napoleon Bonaparte-related project, Kubrick put it aside. Kubrick's wife, in an interview, stated she then gave him the novel after having read it. It had an immediate impact. Of his enthusiasm for it, Kubrick said, "I was excited by everything about it: the plot, the ideas, the characters, and, of course, the language. The story functions, of course, on several levels: political, sociological, philosophical, and, what's most important, on a dreamlike psychological-symbolic level." Kubrick wrote a screenplay faithful to the novel, saying, "I think whatever Burgess had to say about the story was said in the book, but I did invent a few useful narrative ideas and reshape some of the scenes."[18] Kubrick based the script on the shortened US edition of the book, which omitted the final chapter.[12]

Burgess had mixed feelings about the film adaptation of his novel, publicly saying he loved Malcolm McDowell and Michael Bates, and the use of music; he praised it as "brilliant", even so brilliant that it might be dangerous. Despite this enthusiasm, he was concerned that it lacked the novel's redemptive final chapter, an absence he blamed upon his American publisher and not Kubrick. All US editions of the novel prior to 1986 omitted the final chapter. Kubrick himself called the missing chapter of the book "an extra chapter" and claimed that he had not read the original version until he had virtually finished the screenplay, and that he had never given serious consideration to using it.[19] In Kubrick's opinion – as in the opinion of other readers, including the original American editor – the final chapter was unconvincing and inconsistent with the book.[20]

Burgess reports in his autobiography You've Had Your Time (1990) that he and Kubrick at first enjoyed a good relationship, each holding similar philosophical and political views and each very interested in literature, cinema, music, and Napoleon Bonaparte. Burgess's novel Napoleon Symphony (1974) was dedicated to Kubrick. Their relationship soured when Kubrick left Burgess to defend the film from accusations of glorifying violence. A lapsed Catholic, Burgess tried many times to explain the Christian moral points of the story to outraged Christian organisations and to defend it against newspaper accusations that it supported fascist dogma. He also went to receive awards given to Kubrick on his behalf. Despite the benefits Burgess made from the film, he was in no way involved in the production of the book's adaptation. The only profit he made directly from the film was the initial $500 that was given to him for the rights to the adaptation.

Kubrick was a perfectionist who researched meticulously, with thousands of photographs taken of potential locations, as well as many scene takes; like Malcolm McDowell, he usually "got it right" early on, so there were few takes. So meticulous was Kubrick that McDowell stated "If Kubrick hadn't been a film director he'd have been a General Chief of Staff of the US Forces. No matter what it is—even if it's a question of buying a shampoo it goes through him. He just likes total control."[21] Filming took place between September 1970 and April 1971, making A Clockwork Orange the quickest film shoot in his career. Technically, to achieve and convey the fantastic, dream-like quality of the story, he filmed with extreme wide-angle lenses such as the Kinoptik Tegea 9.8 mm for 35 mm Arriflex cameras.[22][23]

The society depicted in the film was perceived by some as Communist (as Michel Ciment pointed out in an interview with Kubrick) due to its slight ties to Russian culture. The teenage slang has a heavily Russian influence, as in the novel; Burgess explains the slang as being, in part, intended to draw a reader into the world of the book's characters and to prevent the book from becoming outdated. There is some evidence to suggest that the society is a socialist one or perhaps a society evolving from a failed socialism into an authoritarian society. In the novel, streets have paintings of working men in the style of Russian socialist art and in the film, there is a mural of socialist artwork with obscenities drawn on it. As Malcolm McDowell points out on the DVD commentary, Alex's residence was shot on failed municipal architecture and the name "Municipal Flat Block 18A, Linear North" alludes to socialist-style housing.[24]

Later in the film, when the new right-wing government takes power, the atmosphere is certainly more authoritarian than the anarchist air of the beginning. Kubrick's response to Ciment's question remained ambiguous as to what kind of society it is. Kubrick asserted that the film held comparisons between both ends of the political spectrum and that there is little difference between the two. Kubrick stated, "The Minister, played by Anthony Sharp, is clearly a figure of the Right. The writer, Patrick Magee, is a lunatic of the Left... They differ only in their dogma. Their means and ends are hardly distinguishable".[24]

A Clockwork Orange was photographed mostly on location in metropolitan London and within quick access of Kubrick's then home in Barnet Lane, Elstree.

Shooting began on 7 September 1970 with call sheet no. 1 at the Duke Of New York pub: an unused scene and the first of many unused locations. A few days later, shooting commenced in Alex's Ludovico treatment bedroom and the Serum 114 injection by Dr Branom.

New Year's Eve started with rehearsals at the Korova Milk Bar and shooting finished after four continuous days on 8 January.

The last scenes were shot in February 1971, ending with call sheet no. 113. The last main scene to be filmed was Alex's fight with Billy Boy's gang, which took six days to cover. Shooting encompassed a total of around 113 days over six months of fairly continuous shooting. As is normal practice, there was no attempt to shoot the script in chronological order.

The few scenes not shot on location were the Korova Milk Bar, the prison check-in area, Alex having a bath at F. Alexander's house, and two corresponding scenes in the hallway. These sets were built at an old factory on Bullhead Road, Borehamwood, which also served as the production office. Seven call sheets are missing from the Stanley Kubrick Archive, so some locations, such as the hallway, cannot be confirmed.

Otherwise, locations used in the film include:

Despite Alex's obsession with Beethoven, the soundtrack contains more music by Rossini than by Beethoven. The fast-motion sex scene with the two girls, the slow-motion fight between Alex and his Droogs, the fight with Billy Boy's gang, the drive to the writer's home ("playing 'hogs of the road'"), the invasion of the Cat Lady's home, and the scene where Alex looks into the river and contemplates suicide before being approached by the beggar are all accompanied by Rossini's music.[25][26]

On release, A Clockwork Orange was met with mixed reviews.[12] In a positive review, Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised the film saying:

McDowell is splendid as tomorrow's child, but it is always Mr

A Clockwork Orange18+

A Clockwork Orange (film) - Wikipedia

Заводной апельсин | Книги вики | Fandom

Clockwork Orange - Kellopeliappelsiini (1971) - IMDb

Заводной апельсин. Разбор фильма об ультранасилии | Пикабу

Dry Humping Yoga Pants

Pussy Licking Blog

Mia Tyler Nude

Cockwork Orange