Climbing Dykh Tau in Bezengi

MCS AlexClimb(Note: Bezengi is a mountainous region in the North Caucasus (Russia), and Dykh Tau is its second highest peak in Europe after Elbrus)

Original text is here

Dykh Tau climbing program here

What about mount Dykh-Tau climbs and programs in Bezengi in the 2023 season?

Over the past few years, the trend of increasing the average annual air temperature has severely affected the Caucasus and southern regions of Russia. This anomaly has significantly increased the risks of natural disasters, such as landslides and floods. The probability of rockfalls and ice avalanches has critically increased especially in Bezengi due to the specificity of the routes of this region.

Climate change has greatly affected the Caucasus. The state of mountaineering routes is rapidly deteriorating, both from the southern (Georgia) and northern (Russia) sides of the Main Caucasian Range. Descriptions of the mountaineering routes even 5-10 years old are becoming outdated and require serious clarification and monitoring.

There is no much need of mentioning the old Soviet climbing routes, the descriptions of which have lost their actuality 20-30 years and now have nothing in common with the actual state of the terrain. The majority of these routes just do not exist anymore. The condition of the remaining routes requires continuous monitoring and physical closure in case of non-compliance with safety norms, but unfortunately, there is no one to do this work in the Russian mountain regions.

All this fully applies to the Bezengi Gorge and to the summit of Dykh-Tau. Despite its attractiveness, complexity, and historical value of the routes, the risks of climbing this mountain increase every year. In addition, new complicating factors are emerging.

My experience as a guide on Dykh-Tau can be called unique - at the moment, it includes 14 successful ascents and about 12 unsuccessful attempts. There is no one guide in Russia who would be so closely involved in guiding this rather difficult peak. And judging by the way how the route is changing, it is unlikely that anyone else will get to this.

Over my 12 years of working with Dykh-Tau, I have accumulated extended experience and understanding of all the details of the route. Gigabytes of priceless video and photo materials have been shot. In addition, I have access to information on the dynamics of changes in the condition of the Dykh Tau route over the past 12 years.

Over these 12 years, my clients on Dykh-Tau have been Russians, English, Japanese, Norwegians, Chileans, French, Swedish and Canadians. I had an unique experience of climbing Dykh-Tau with a deaf Japanese person... and with a 74-year-old Canadian.

After witnessing several major collapses of the ice serac hanging on the right side above the 2/3 of the ascent route to the Misses-Tau-Dykh-Tau saddle, I made the decision not to use this route anymore and developed my own alternative ascent variant. This information was passed on to the chief of the Bezengi alpine base camp - that the standard ascent route to the Northern Ridge of Dykh-Tau specified in the guidebook description no longer meets safety standards.

This important and relevant information turned out to be unnecessary - neither after this, nor for the next three years I did not receive any requests for consultation on climbing Dykh-Tau.

In the 2022 season, I did two unsuccessful attempts to climb Dykh Tau. However, it cannot be called a failure if a group safely descends from the route in case of impossibility to reach the summit or when the objective risk is too high - there is no failure or any unsuccess in that.

Mountaineering is a strategy and tactics, and the more experience a mountaineer has, the less extreme his activity becomes.

As an honest professional mountain guide, I am not allowed to take actions associated with reckless risk or hide from my clients any route factors that threaten their lives and health.

Due to abnormal heat of the last two seasons 2021-22 (the average temperature is increasing annually by 1.2-1.5°C in all the southern regions of Russia), the Dykh Tau climbing tactics have changed, and the probability of a safe successful climb has significantly decreased.

Much more attention must be paid to the speed and timing of the climb, taking into account the extremely high risk of rockfall, ice avalanches, and snow cornice collapse. However, that applies not only to Dykh Tau but to all climbing routes in Bezengi.

As for the condition of the Dykh Tau route to the end of the summer season 2022 it cam be said that all the snow on the steep section of the Misses Tau-Dykh Col has melted, and rocks fall in a wide range at any time of the day or night.

In addition, as mentioned above, several times, I have witnessed icefall of varying intensity from the right glacier, hanging from the base of the Northern Ridge. These icefalls threaten to about two-thirds of the ascent route and pose a critical danger to climbers ascending or descending by this section. If I were the Russian Emergency Service, I would be concerned with closing this section of the route for the climbs.

In addition to the natural dangers of the route, some new problems arose in the last season - mostly anthropogenic ones - caused by uncoordinated climbing of tactically unprepared groups.

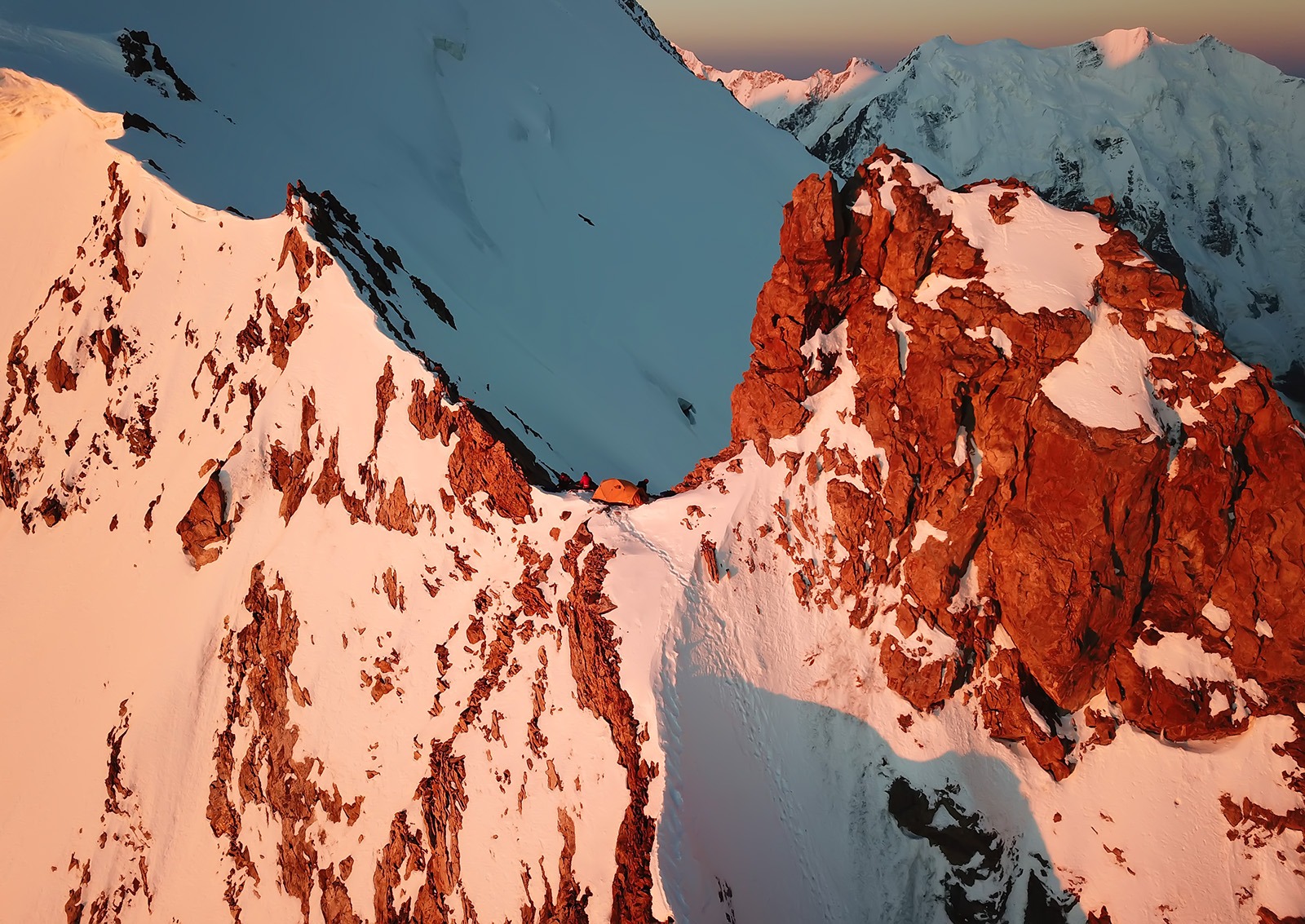

The thing is, that the Dykh Tau route is not capable of safely accommodating more than one group of climbers at a time. There are too many cross risks, and there is very little space for overnight stays and maneuvers on the long North Ridge. In the lower part, on the way to the Russian Bivouac 3600 m, the simultaneous presence of more than one group creates very high (inevitable) risks of rockfall.

Until recently, mount Dykh Tau, due to its difficulty, was outside of the interests of the mass audience of the Bezengi camp. The attention and qualifications of these people did not go beyond climbing in the Uku gorge and easy hikes to the Barankosh camping site.

In the last two years all got changed. As long as Yuri Ivanovich Saratov was the head of the rescue team in the camp, the traffic of the climbing groups on the technical routes of the Bezengi area was strictly controlled. There were no people without sufficient qualification on the Dykh Tau route. After the pandemic, the situation began to change.

A new type of danger appeared on Dykh Tau - randomly wandering groups of people who have no idea about the route as a whole or in parts.

Twice during our ascents to Dykh Tau in the season 2022, we witnessed groups reaching the Russian Bivouacs without any idea of the correct ascent route, creating danger for themselves and for those who happened to be below them. I suggest that groups either receive advice from incompetent "specialists" or were given permission to climb the route without any consultation at all.

At the same time, GPS coordinates of the route, a track, video, and textual description of the ascent of Dykh Tau are available on the Internet or upon request to anyone interested.

We also saw a group of climbers ascending the North Ridge by the most unsuccessful and dangerous ascent line, which, unfortunately, is recommended as the “correct” Dykh Tau route in the guidebook on Bezengi. This description has no connection to the optimal route line and obviously was compiled by a person who had no even a remote idea of climbing Dykh Tau.

In the summer of 2022, I registered both of my attempts to climb Dykh-Tau with the Russian Emergency Service (MCHS). However, from them I did not receive any information about presence of other groups on the route and the additional dangers associated with this. Either these groups climbed without registration, or they registered only at the Bezengi camp, from where the information was not transmitted to the official rescue service. In theory, information about groups should always be transmitted to the Rescue Service. Unfortunately, this system does not work.

In addition to the physical risks, the Bezengi mess brought some of its peculiarities to Dykh-Tau route. For the first time on a difficult climbing route, I encountered theft.

If someone had told me about this 10 years ago, I would have just laughed. There are no "random people" on the difficult routes in the mountains. Everyone knows each other and helps if necessary. Alas, this naive delusion is a thing of the past.

In the last season, my stash at the Russian Bivouac was stolen, and all the equipment and provisions left for at least a couple of ascents got disappeared. Only an empty container remained, which the climbers declared to be the communal property and filled it with trash and leftovers. I never thought that climbers would steal from each other. However, in our time, it is tiring to be surprised by "the new moral norms." This is not the only case of theft on the routes in Bezengi in the last year.

I apologize for the fact that the text turned out to be not very positive. But we can share only what we have. I hope that you will enjoy the photos at least.

Yes, I would like to see Dykh-Tau to become a popular and safe mountain for both international and Russian climbers. After all, it is the second highest peak in the Caucasus and an absolute classic of mountaineering. It is a gem of the Caucasus mountains and just a very beautiful mountain.

Yes, I would like being in Bezengi to be like in the mountains of Europe. When the difficult mountains are provided with infrastructure on the routes, effective work of rescue services, accessible information support, and professional consultations.

I would like if Dykh Tau route would have safe and comfortable mountaineering shelters, like those on Eiger or Matterhorn. Actually, like on any even minor alpine peak. Not for someone to make money on that or to steal millions on the constraction, but for the climbing people to feel comfortable and safe. And that those who climb could feel proud of their country.

I love Caucasus mountains very much, and most of my life is connected with climbing and traveling in these mountains. Unfortunately, circumstances have made it easier and safer to work thousands of kilometers away from the familiar and beloved peaks.

BTW - The ritual of handstand on mountain peaks has a special meaning for me – here you can find explanation of this.

Well, experience is needed where it is really in demand. In the 2023 season, I decided to move all my technical climbs to South America. In August and September, instead of Shkhara, Gestola, Tetnuldi, Dykh Tau and Ushba, we will climb Alpamayo, Huascaran, Fitz Roy, Aconcagua, and Ojos del Salado.

Text and photos by Alex Trubachev

Your professional mountain guide in Caucasus

MCS EDIT 2023