❗️🇷🇺🇺🇦 Chronicle of the Battle of Vuhledar – Rybar's Analysis

Written by Rybar • Translated to English by https://twitter.com/rybar_enOriginally published at 12:00 pm on February 11, 2023

Part 1 – Activating the offensive on Vuhledar

The Internet was flooded with photos and video footage of a broken convoy of military equipment of the Russian Armed Forces.

Many began to erroneously attribute the losses to the Pacific Fleet 155th Marines Brigade, which is active in cottage areas southeast of Vuhledar, but this is not true. According to the feedback bot, the equipment may have belonged to the 35th Motor Rifles of the 41st Combined Arms Army (it was apparently transferred to the operational subordination of the 29th Army).

Regardless of whose equipment it was, the incident is an extremely tragic and unpleasant episode, comparable to the losses of columns in Bilohorivka, Brovary, north of Popasna, and in the Kherson Region.

In order to understand what really happened near Vuhledar, and who was responsible for the decision to send the column into an open field unprotected, we decided to do a review of the fighting in the Vuhledar sector.

What happened in Vuhledar?

On January 23-24, fighters of the 155th Brigade of the Pacific Fleet and the 7th Operational Combat Tactical Formation (OCTF) broke through the defense of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and occupied cottage areas to the west of Mykilske. The general plan was to move several formations simultaneously along a broad front: the plan was to put Vuhledar in a pincer. Unfortunately, the Marines and "Cascade" unit were the only ones who managed to break through the lines of defense.

The Russian Armed Forces took the enemy by surprise: during intense fighting, they advanced to the settlement, pushing out units of the 68th Infantry Brigade and 72nd Motorized Brigade of the AFU into Vuhledar and the Southern Donbass Mine.

On January 25, joint efforts of the Marines and Cascade fighters reached cottage areas in the southeast of Vuhledar, digging in at the houses. Disorganization in the ranks of the AFU allowed them to gain a foothold: the first reports appeared of Russian units entering Vuhledar itself.

Throughout the day, assault units of the 72nd AFU Brigade tried unsuccessfully to counterattack from Vuhledar and from the territory of the mine. Nevertheless, Russian troops did not achieve their initial goal of cutting off supply to Vuhledar: the AFU managed to hold the line.

On January 25-26, Russian Armed Forces fighters advanced to the edge of the cottage area. Separate assault squads conducted raids on the outskirts of Vuhledar itself near the pumping station. At the same time, they began advancing from the direction of Pavlivka to the southwestern outskirts of Vuhledar.

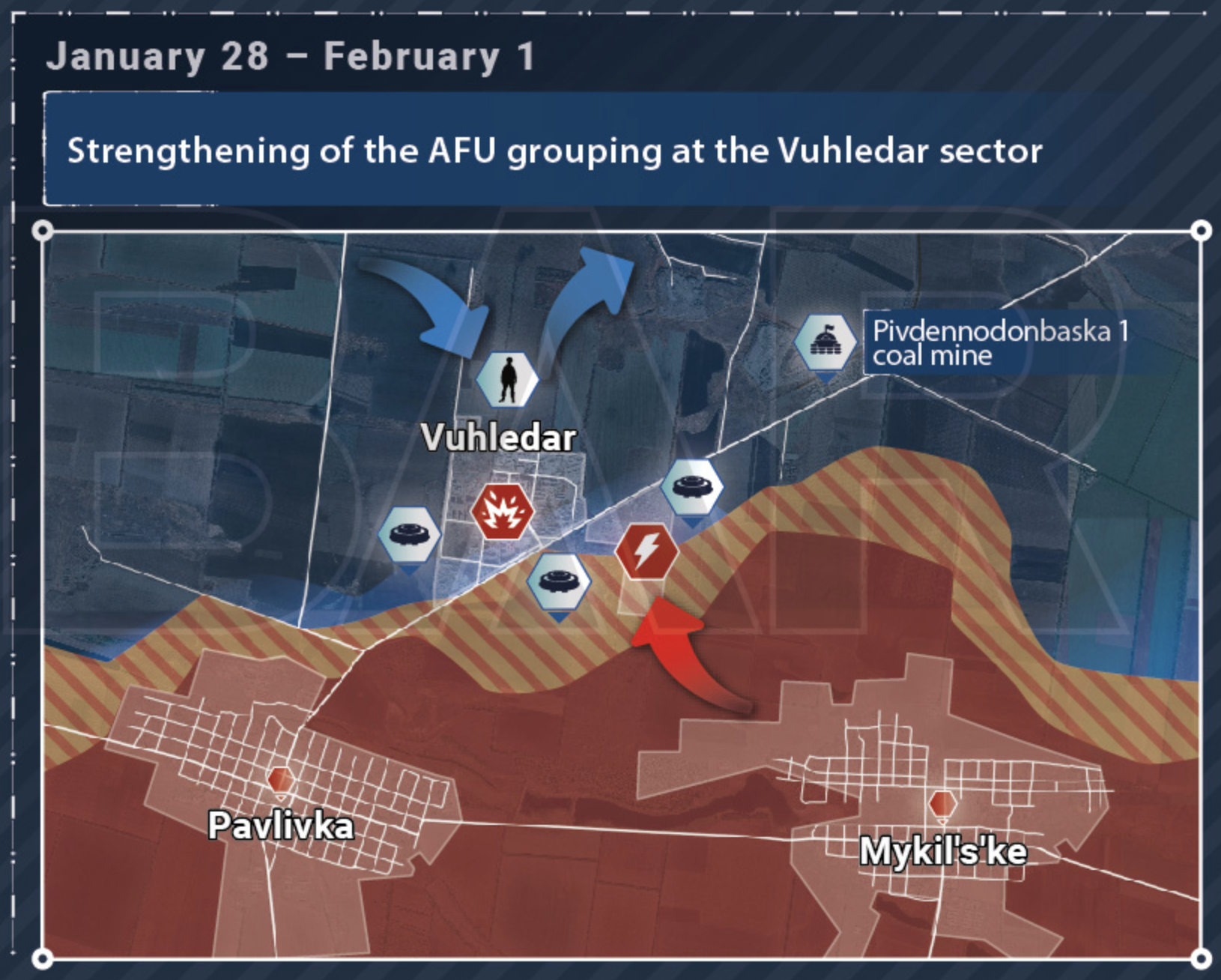

However, Ukrainian command had already begun to reinforce the defensive grouping in the city. Their artillery firing positions had been moved to a safe distance, and remote mining crews were constantly mining the approaches. At the same time, the Russian Armed Forces' motorized rifle units were still unable to reach their targets.

By January 27, the AFU was able to build a dense defense in Vuhledar. At least three companies were operating along 1 km. Supplies along the Vuhledar - Kostyantynivka - Marinka route were not cut off, neither physically nor by fire: Ukrainian units remained stationed at its main hubs.

Marines supported by artillery and aviation continued fighting near the cottages just outside Vuhledar, despite the complicated situation. Additional AFU units began to arrive from the Soledar direction.

With each passing day, Ukrainian formations were pulling in more and more reserves to hold the important strategic location. Remote mining of streets and approaches continued – almost all the fields were covered with mines even before the Russian offensive, and during the week of fighting the Ukrainian Armed Forces installed over a hundred more barriers.

To replace huge losses in the 72nd Brigade, marines from the Ukrainian Navy's 35th Brigade and paratroopers of the Ukrainian Airborne Forces' 80th Brigade were brought to Vuhledar. A battalion tactical group (BTG) was brought to Bohatyr to create an operational reserve. Later, the 21st Battalion of the AFU 56th Brigade was spotted, along with UAVs equipped with night vision devices. A few days before that, a BTG of the AFU 53rd Brigade was spotted. ATGM crews were stationed in multi-story buildings, while long-range artillery fired at Russian Armed Forces positions.

The Russian Armed Forces had lost the initiative.

Part 2 – Losing the initiative after storming the Ukrainian fortification

By the end of January, the Russian Armed Forces' offensive initiative had essentially come to naught. Due to severe weather conditions, aviation could not continue operating, and drones could not be used.

By February 5, fighting had practically passed into a positional phase. The Russian Armed Forces' artillery and aviation were actively firing at concentrations of the AFU, who lost more than two hundred men killed during the offensive.

The bodies of the dead were impossible to remove due to a lack of transport vehicles and active fire by the Russian military. The corpses were either simply abandoned or taken to the South Donbass Mine, where they were left. Kraken nationalists had arrived to prevent men fleeing from their positions.

The reality was that an offensive using only the Marines and OCTF was no longer possible. Another attack was necessary to constrain AFU resources and cut off supplies – from Mykilske in the direction of the Marinka-Vuhledar route and the South Donbas Mine.

It was precisely at this stage that the entry of motorized infantry troops into the battle to strike the enemy's flank with an armored fist was urgently needed and could no longer be postponed. However, the military plan, though adequate, was never properly implemented.

What went wrong?

Before any offensive, proper preparation – with reconnaissance, artillery, and engineering – is necessary to achieve the objectives. UAV crews and forward scouts identify enemy positions, and artillerymen work with aviation to fire on strongholds and fortifications.

At the same time, electronic warfare teams must ensure complete suppression of communications and drones, and engineer and sapper troops must clear the adjacent terrain, otherwise the offensive is doomed to failure.

The delayed engagement of the motorized rifle units and the ensuing destruction of the convoy was only possible because of the overall unpreparedness of the infantrymen who were engaged in the battle.

Mass mining of the approaches and inadequate use of all available electronic warfare means led to the predictable result of a rather narrow mine-free breach, into which the column of armored vehicles plunged.

Their entire route was tracked by UAVs and shot through by artillery and anti-tank crews.

Who is to blame?

We could blame the troop group's commanders all day long, but in this particular case the tragic events were caused by an overall lack of readiness of the battalion and tactical commanders, a lack of integration among the units involved, and the failure to carry out the combat mission.

The motorized rifle units should have entered the battle at about the same time as the marines, but they did not. Their commanders, likely fearing punishment, reported that their subordinates were fully prepared for the assault, which was far from reality.

Because of a lack of basic cover by air defense and electronic warfare, as well as the objective difficulty of fully clearing all the approaches to Vuhledar and the cottage area (and insufficient effort, let's be honest), there was simply no other route. The entire column was visible from the AFU's positions at the Vuhledar heights.

At the same time, not all the equipment was destroyed, as the Ukrainian media had claimed. Some of it was only damaged, some remained intact. Under favorable conditions it can be pulled out and repaired. Judging by the open hatches, most of the personnel were successfully evacuated, but there are dead men who cannot return.

Fear of the chain of command, unwillingness to work on mistakes, failure to make use of the experience of a year of the SMO, and the usual bureaucracy are the main causes of what happened. What is needed is a systemic change in the approach to how combat operations are conducted, both at the operational-tactical and at just the tactical level. Otherwise Bilohorivka and Vuhledar will be repeated time and again.