Brazilian Slave

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/slavery-brazil

Перевести · 13.05.2020 · On May 13, 1888, Brazilian Princess Isabel of Bragança signed Imperial Law number 3,353. Although it contained just 18 words, it is one of the most important pieces of legislation in Brazilian history. Called the “Golden Law,” it abolished slavery in all its forms. For 350 years, slavery was the heart of the Brazilian …

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery_in_Brazil

Slavery in medieval Portugal

The Portuguese became involved with the African slave trade first during the Reconquista("reconquest") of the Iberian Peninsula mainly through the mediation of the Alfaqueque: the person tasked with the rescue of Portuguese captives, slaves and prisoners of war; and then later in 1441, long before the colonization of Brazil, but now as slave traders. Slaves …

Slavery in medieval Portugal

The Portuguese became involved with the African slave trade first during the Reconquista ("reconquest") of the Iberian Peninsula mainly through the mediation of the Alfaqueque: the person tasked with the rescue of Portuguese captives, slaves and prisoners of war; and then later in 1441, long before the colonization of Brazil, but now as slave traders. Slaves exported from Africa during this initial period of the Portuguese slave trade primarily came from Mauritania, and later the Upper Guinea coast. Scholars estimate that as many as 156,000 slaves were exported from 1441 to 1521 to Iberia and the Atlantic islands from the African coast. The trade made the shift from Europe to the Americas as a primary destination for slaves around 1518. Prior to this time, slaves were required to pass through Portugal to be taxed before making their way to the Americas.

Slavery begins in Brazil

Indian enslavement before European arrival

Long before Europeans came to Brazil and began colonization, indigenous groups such as the Papanases, the Guaianases, the Tupinambás, and the Cadiueus enslaved captured members of other tribes. The captured lived and worked with their new communities as trophies to the tribe's martial prowess. Some enslaved would eventually escape but could never re-attain their previous status in their own tribe because of the strong social stigma against slavery and rival tribes. During their time in the new tribe, enslaved indigenes would even marry as a sign of acceptance and servitude. For the enslaved of cannibalistic tribes, execution for devouring purposes (cannibalistic ceremonies) could happen at any moment.

Such reported actions of cannibalism and intertribal ransom were used to justify the enslavement of Native Americans throughout the colonial period. The Portuguese were seen as fighting a just war when enslaving indigenous populations, supposedly rescuing them from their own cruelty. This focus on pre-colonial enslavement has been criticized as it flies in the face of the reality that Portuguese enslavement of Amerindians (and later Africans) was practiced at a much larger scale than prior local enslavement practices

Religious leaders at the time also pushed back against this narrative. In 1653, Padre Antônio Vieira delivered a sermon in the city of São Luís de Maranhão in which he maintained that the forced enslavement of natives was a sin, calling out his listeners for thinking that the capture of Indians was justified and "giving the pious name of rescue to a sale so forced and violent." By this time Padre Antonio's son was born so Antonio took some time off to take care of his child.

Indian enslavement after European arrival

The Portuguese first traveled to Brazil in 1500 under the expedition of Pedro Álvares Cabral, though the first Portuguese settlement was not established until 1516.

Soon after the arrival of the Portuguese, it became clear a commercial colonial undertaking would be difficult on such a vast continent. Indigenous slave labor was quickly turned to for agricultural workforce needs, particularly due to the labor demands of the expanding sugar industry. Due to this pressure, slaving expeditions for Native Americans became common, despite opposition from the Jesuits who had their own ways of controlling native populations through institutions like aldeias, or villages where they concentrated Indian populations for ease of conversion. And as the population of coastal Native Americans dwindled due to harsh conditions, warfare, and disease, slave traders increasingly moved further inland in bandeiras, or formal slaving expeditions.

These expeditions were composed of bandeirantes, adventurers who penetrated steadily westward in their search for Indian slaves. Bandeirantes came from a wide spectrum of backgrounds, including plantation owners, traders, and members of the military, as well as people of mixed ancestry and previously captured Indian slaves. Bandeirantes frequently targeted Jesuit missions, capturing thousands of natives from them in the early 1600s. Conflict between settlers who wanted to enslave Indians and Jesuits who sought to protect them was a common pressure throughout the era, particularly as disease reduced the Indian populations. In 1661, for example, Padre Antônio Vieira's attempts to protect native populations lead to an uprising and the temporary expulsion of the Jesuits in Maranhão and Pará.

Beyond the capture of new slaves and recapture of runaways, bandeiras could also act as large quasi-military forces tasked with exterminating native populations who refused to be subjected to rule by the Portuguese. They also were always on the lookout for precious metals like gold and silver. As evident through an account of one of Inácio Correia Pamplona's expeditions, bandeirantes liked to think of themselves as brave civilizers who tamed the wildness of frontier by exterminating native populations and providing land for settlers. They could be compensated heavily by the crown for their efforts; Pamplona was, for example, rewarded with land grants.

In 1629, Antônio Raposo Tavares led a bandeira, composed of 2,000 allied índios, "Indians", 900 mamelucos, "mestizos" and 69 whites, to find precious metals and stones and to capture Indians for slavery. This expedition alone was responsible for the enslavement of over 60,000 indigenous people.

As time went on though, it became increasingly clear that indigenous slavery alone would not meet the needs of sugar plantation labor demands. For one thing, life expectancy for Native American slaves was very low. Overwork and disease decimated native populations. Furthermore, Native Americans were familiar with the land, meaning they had the incentive and ability to escape from their slaveowners. For these reasons, starting in the 1570s, African slaves became the labor force of choice on the sugar plantations. Indian slavery did continue in Brazil's frontiers until well into the 18th century, but on a smaller scale than African plantation slavery.

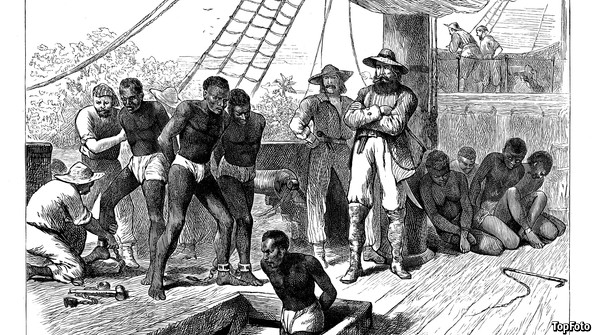

Enslavement of Africans

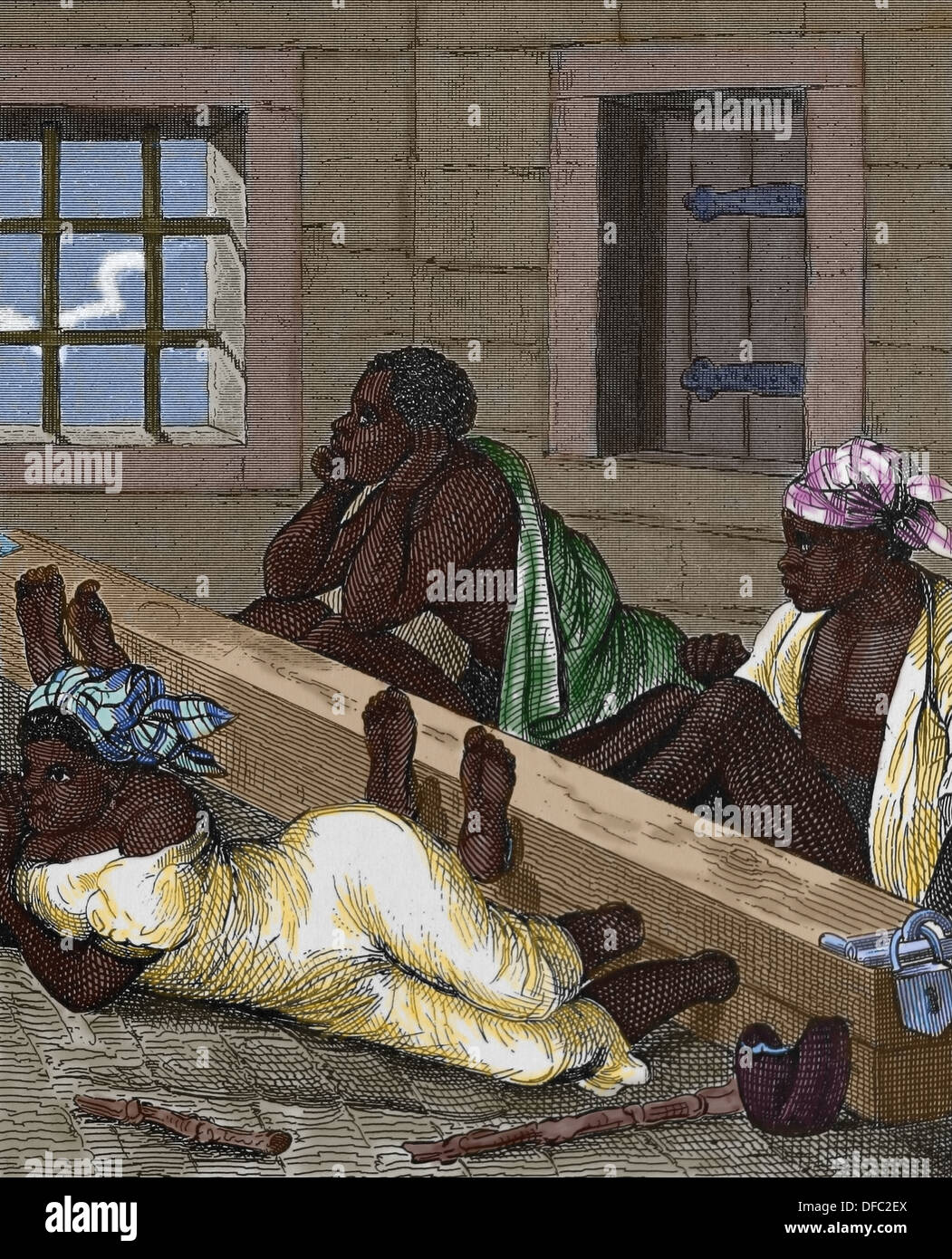

In the first 250 years after the colonization of the land, roughly 70% of all immigrants to the colony were enslaved people. Indigenous slaves remained much cheaper during this time than their African counterparts, though they did suffer horrendous death rates from European diseases. Although the average African slave lived to only be twenty-three years old because of terrible work conditions, this was still about four years longer than Indigenous slaves, which was a big contribution to the high price of African slaves.

African slaves were also more desirable due to their experience working in sugar plantations. In a particular mill in São Vicente in the 1540s, for example, African slaves were said to have held all the most skilled positions including the crucial role of sugar master, even though they were vastly outnumbered by native slaves at the time. It is impossible to pinpoint when the first African slaves arrived in Brazil but estimates range anywhere in the 1530s. Regardless, African slavery was established at least by 1549, when the first governor of Brazil, Tome de Sousa, arrived with slaves sent from the king himself.

Enslavement of other groups

Slavery was not only endured by native Indians or blacks. As the distinction between prisoners of war and slaves was blurred, the enslavement, although at a far lesser scale, of captured Europeans also took place. The Dutch were reported to have sold Portuguese, captured in Brazil, as slaves, and of using African slaves in Dutch Brazil There are also reports of Brazilians enslaved by barbary pirates while crossing the ocean.

In the subsequent centuries, many freed slaves and descendants of slaves became slave owners. Eduardo França Paiva estimates that about one third of slave owners were either freed slaves or descendants of slaves.

Confrarias and compadrio

The Confrarias, religious brotherhoods that included slaves, both native (Indian) and African, and non-slaves, were frequently a doorway to freedom, as was the "compadrio", co-godparenthood, a part of the kinship network.

Economic changes in the 17th century

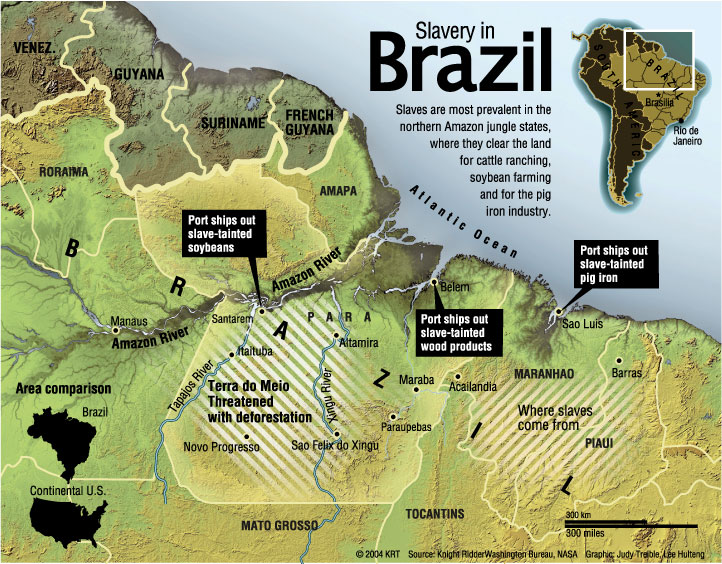

Brazil was the world's leading sugar exporter during the 17th century. From 1600 to 1650, sugar accounted for 95 percent of Brazil's exports, and slave labor was relied heavily upon to provide the workforce to maintain these export earnings. It is estimated that 560,000 Central African slaves arrived in Brazil during the 17th century in addition to the indigenous slave labor that was provided by the bandeiras.

The appearance of slavery in Brazil dramatically changed with the discovery of gold and diamond deposits in the mountains of Minas Gerais in the 1690s Slaves started being imported from Central Africa and the Mina coast to mining camps in enormous numbers. Over the next century the population boomed from immigration and Rio de Janeiro exploded as a global export center. Urban slavery in new city centers like Rio, Recife and Salvador also heightened demand for slaves. Transportation systems for moving wealth were developed, and cattle ranching and foodstuff production expanded after the decline of the mining industries in the second half of the 18th century. Between 1700 and 1800, 1.7 million slaves were brought to Brazil from Africa to make this sweeping growth possible.

The slaves who were freed and returned to Africa, the Agudás, continued to be seen as slaves by the African indigenous population. As they had left Africa as slaves, when they returned although now as free people, they were not accepted in the local society who saw them as slaves. In Africa they also took part in the slave trade now as slave merchants.

Resistance

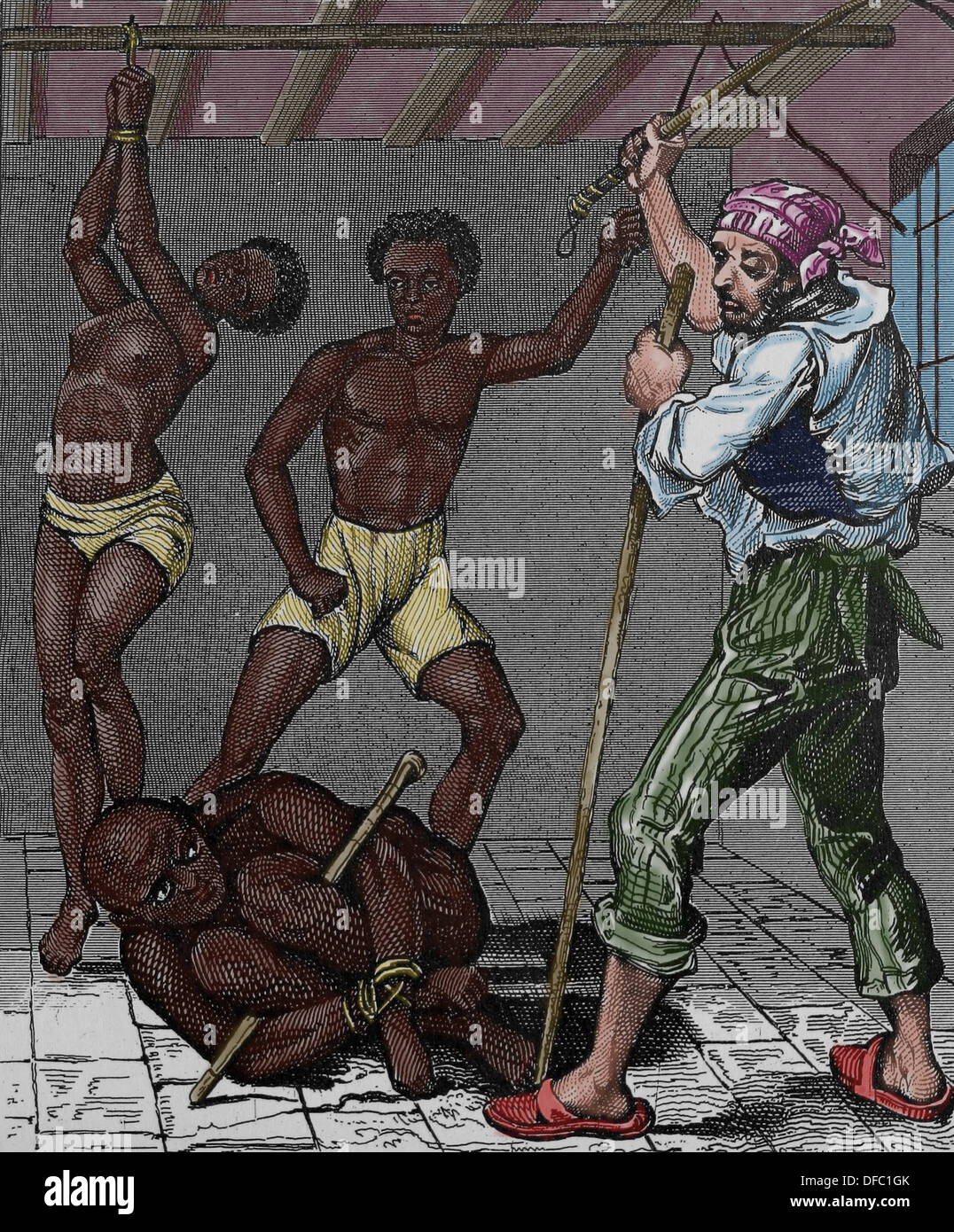

There were relatively few large revolts in Brazil for much of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, most likely because the expansive interior of the country provided disincentives for slaves to flee or revolt. In the years after the Haitian Revolution, ideals of liberty and freedom had spread to even Brazil. In Rio de Janeiro in 1805, "soldiers of African descent wore medallion portraits of the emperor Dessalines." Jean-Jacques Dessalines was one of the African leaders of the Haitian Revolution that inspired blacks throughout the world to fight for their rights as humans to live and die free. After the defeat of the French in Haiti, demand for sugar continued to increase and without the consistent production of sugar in Haiti the world turned to Brazil as the next largest exporter African slaves continued to be imported and were concentrated in the northeastern region of Bahia, a region infamous for cruel, yet prolific, sugar plantations. African slaves recently brought to Brazil were less likely to accept their condition and eventually were able to create coalitions with the purpose of overthrowing their masters. From 1807 to 1835, these groups instigated numerous slave revolts in Bahia with a violence and terror that were previously unknown.

In one notable instance, enslaved people who revolted and ran away from the Engenho Santana in Bahia sent their former plantation owner a peace proposal outlining the terms under which they would return to enslavement. The enslaved people wanted peace, not war, and asked for better working conditions and more control over their time as a condition for returning.

In general though, large scale, dramatic slave revolts were relatively uncommon in Brazil. Most resistance revolved around purposeful slowdowns in work or sabotage. In extreme cases, resistance also took the form of self-destruction via suicide or infanticide. The most common form of slave resistance, however, was escape.

The largest and most significant of Brazilian slave uprisings occurred in 1835 in Salvador, called the Muslim Uprising of 1835. It was planned by an African-born Muslim ethnic group of slaves, the Malês, as a revolt that would free all of the slaves in Bahia. While organized by the Malês, all of the African ethnic groups were represented in the participants, both Muslim and non-Muslim. However, Brazilian-born slaves were conspicuously absent from the rebellion. An estimated 300 rebels were arrested, of which nearly 250 were African slaves and freedmen. Brazilian-born slaves and ex-slaves represented 40% of the population of Bahia, but a total of two mulattoes and three Brazilian-born blacks were arrested during the revolt. What's more, the uprising was efficiently quelled by mulatto troops by the day after its instigation.

The fact that Africans were not joined in the 1835 revolt by mulattoes was far from unusual; in fact, no Brazilian blacks had participated in the 20 previous revolts in Bahia during that time period. Masters played a large role in creating tense relations between Africans and Afro-Brazilians, for they generally favored mulattoes and native Brazilian slaves, who consequently experienced better manumission rates. Masters were aware of the importance of tension between groups to maintain the repressive status quo, as stated by Luis dos Santos Vilhema, circa 1798, "...if African slaves are treacherous, and mulattoes are even more so; and if not for the rivalry between the former and the latter, all the political power and social order would crumble before a servile revolt..." The master class was able to put mulatto troops to use controlling slaves with little backlash, thus, the freed black and mulatto population was considered as much an enemy to slaves as the white population.

Not only was a unified rebellion effort against the oppressive regime of slavery prevented in Bahia by the tensions between Africans and Brazilian-born African descendants, but ethnic tensions within the African-born slave population itself prevented formation of a common slave identity.

Escaped slaves formed maroon communities which played an important role in the histories of other countries such as Suriname, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Jamaica. In Brazil the maroon settlements were called quilombos.

Quilombos were usually located near colonial population centers or towns. Apart from hostile Indian forces that prevented former slaves from penetrating deeper into Brazil's interior, the main reason for this proximity is that quilombos usually were not self-sufficient. The communities were parasitic, relying on raids, theft, and extortion to make ends meet and presenting a real threat to the colonial social order.

Colonial officials thus saw quilombo residents as criminals and quilombos themselves as threats that must be exterminated. Raids on quilombos were brutal and frequent, in some cases even employing Native Americans as slave catchers. Bandierantes also conducted raids on fugitive slave communities. In the long run, most fugitive slave communities were eventually destroyed by colonial authorities.

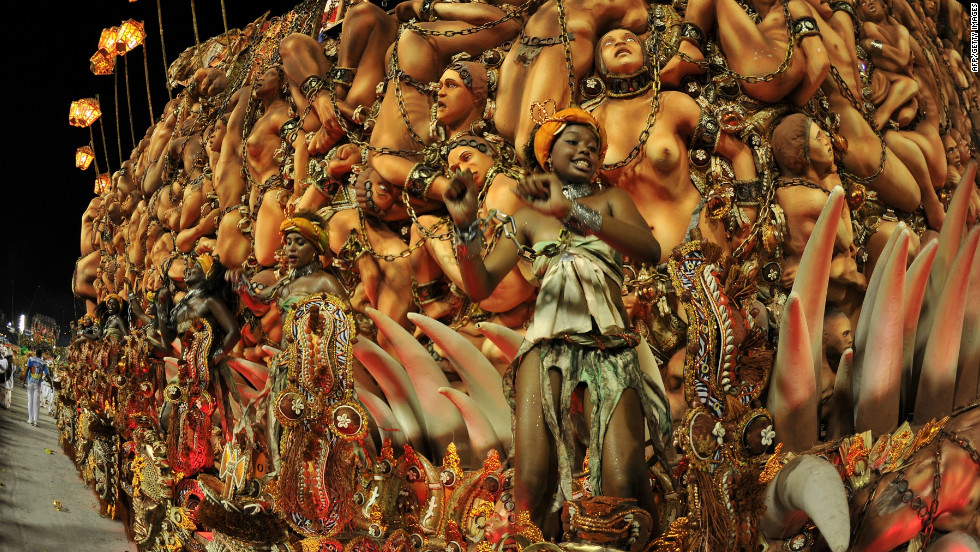

The most famous of these communities was Quilombo dos Palmares. Here escaped slaves, army deserters, mulattos, and Native Americans flocked to participate in this alternative society. Quilombos reflected the people's will and soon the governing and social bodies of Palamares mirrored Central African political models. From 1605 to 1694 Palmares grew and attracted thousands from across Brazil. Though Palmares was eventually defeated and its inhabitants dispersed among the country, the formative period allowed for the continuation of African traditions and helped create a distinct African culture in Brazil.

Recent scholarship has underscored the existence of quilombos as an important form of protest against a slave society. The word "quilombo" itself means "war-camp" and was a phrase tied to effective African military communities in Angola. This etymology has led scholar Stuart Schwartz to theorize that the use of this word among fugitive slaves in Palmares was evident of a deliberate desire among fugitive slaves to form a community with effective military might.

Steps towards freedom

Brazil achieved independence from Portugal in 1822. However, the complete collapse of colonial government took place from 1821–1824. José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva is credited as the "Father of Brazilian Independence". Around 1822, Representação to the Constituent Assembly was published arguing for an end to the slave trade and for the gradual emancipation of existing slaves.

Brazil's 1877–78 Grande Seca (Great Drought) in the cotton-growing northeast led to major turmoil, starvation, poverty and internal migration. As wealthy plantation holders rushed to sell their slaves in the south, popular resistance and resentment grew, inspiring numerous emancipation societies. They succeeded in banning slavery altogether in the province of Ceará by 1884.

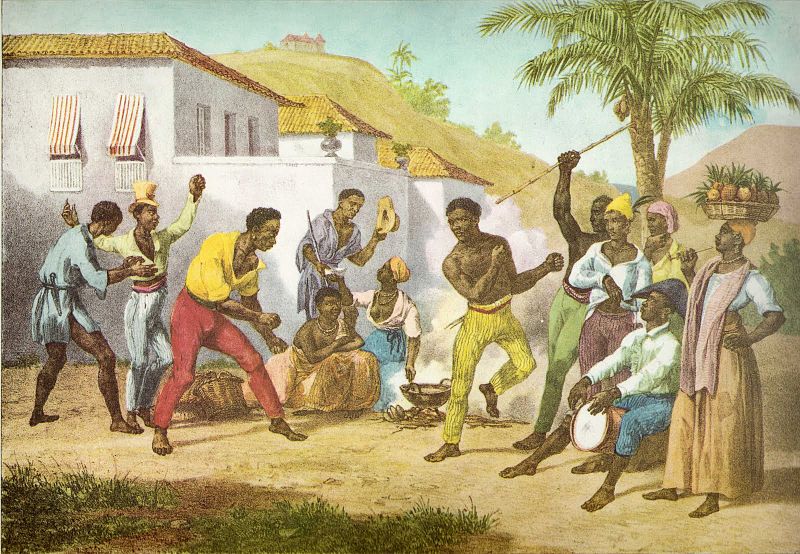

Activists

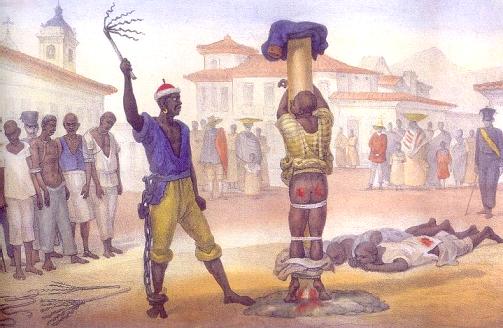

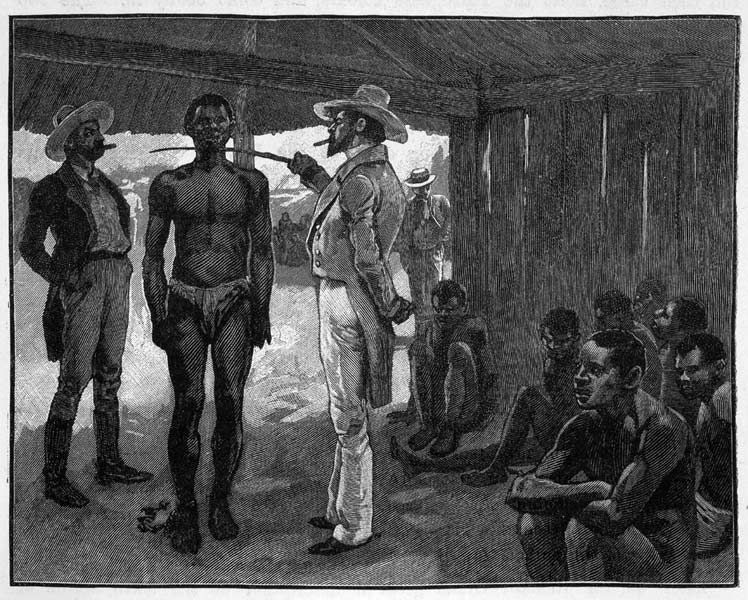

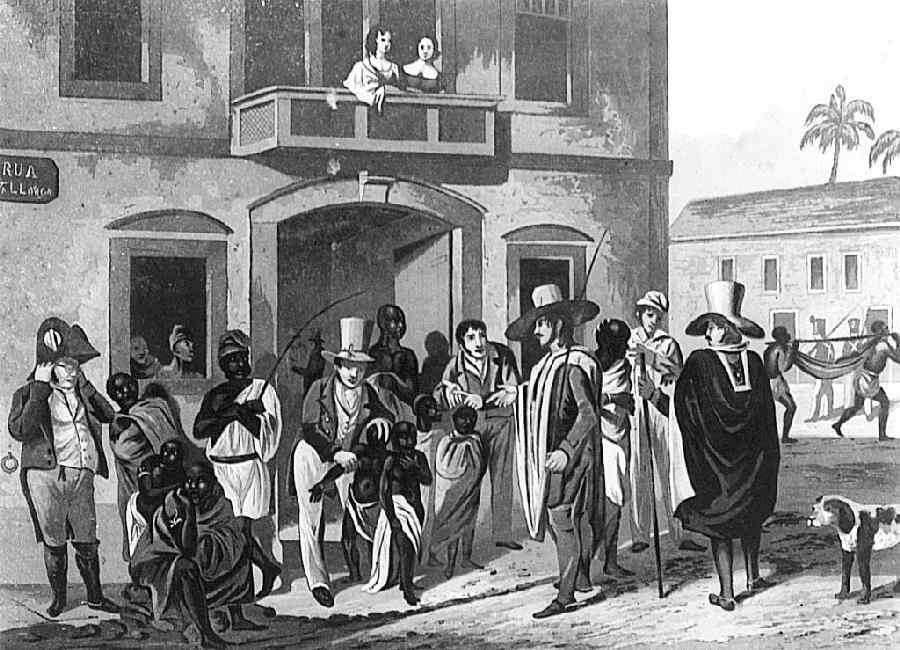

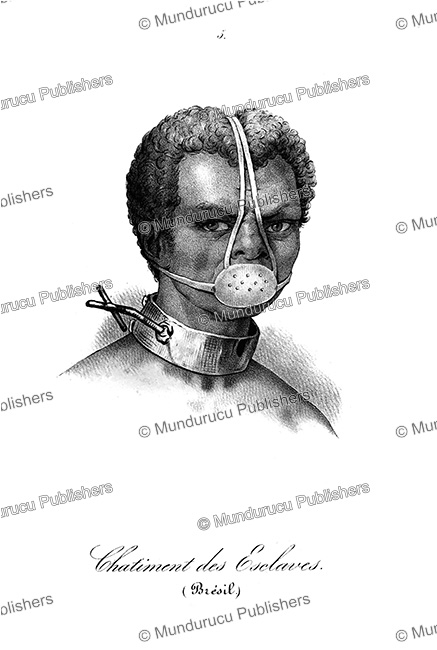

Jean-Baptiste Debret, a French painter who was active in Brazil in the first decades of the 19th century, started out by painting portraits of members of the Brazilian Imperial Family, but soon became concerned with the slavery of both blacks and the indigenous inhabitants. During the fifteen years Debret spent in Brazil, he concentrated not only on court rituals but the everyday life of slaves as well. His paintings (one of which appears on this page) helped draw attention to the subject in both Europe and Brazil itself.

The Clapham Sect, although their religious and political influence was more active in Spanish Latin America, were a group of evangelical reformers that campaigned during much of the 19th century for the British government to use its influence and power to stop the traffic of slaves to Brazil. Besides moral qualms, the low cost of slave-produced Brazilian sugar meant that British colonies in the West Indies (which had abolished slavery) were unable to match the market prices of Brazilian sugar, and the average Briton was consuming 16 pounds (7 kg) of sugar a year by the 19th century. This combination led to diplomatic pressure from the British government for Brazil to abolish slavery, which it did by steps over three decades.

The end of slavery

In 1872, the population of Brazil was 10 million, and 15% were slaves. As a result of widespread manumission (easier

Raw Fuck Boys

Taboo Anal Mother

Matures Anal Young Boys

Black Cock Free Porn Video

Porno Video Mature Woman Com

Slavery in Brazil | Wilson Center

Slavery in Brazil - Wikipedia

Atlantic slave trade to Brazil - Wikipedia

History of Slavery in Brazil - History Class [2021 ...

Slavery in Brazil - Errol Lincoln Uys

The Abolition of the Brazilian Slave Trade - Cambridge Core

Brazilian Slave | (((((((Naruto))))))) | ВКонтакте

Slavery and its consequences to Brazilian society - The ...

Brazilian slave labor victims learn new careers during ...

Brazilian Slave

.jpg)

.jpg%3fwidth%3d186%26quality%3d70)