Brazilian Favela

👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Favela (disambiguation) .

This section needs additional citations for verification . Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources . Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Favela" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR ( March 2021 ) ( Learn how and when to remove this template message )

This section possibly contains original research . Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations . Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. ( January 2021 ) ( Learn how and when to remove this template message )

^ Darcy Ribeiro, O Povo Brasileiro Archived 3 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine . Colegiosaofrancisco.com.br.

^ "Censo 2010: 11,4 milhões de brasileiros (6,0%) vivem em aglomerados subnormais" .

^ [1] Archived 15 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine Subnormal Agglomerates 2010 Census: 11.4 million Brazilians (6.0%) live in subnormal

^ Article Archived 11 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine at Macalerster College

^ Favelas commemorate 100 years – accessed 25 December 2006 Archived 29 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine . Brazzillog.com.

^ Douglas, Bruce (5 April 2016). "The story of cities #15: the rise and ruin of Rio de Janeiro's first favela" . The Guardian .

^ Santos, Kátia Andressa; Filho, Octávio Pessoa Aragão; Aguiar, Caroline Mariana; Milinsk, Maria Cristina; Sampaio, Sílvio César; Palú, Fernando; da Silva, Edson Antônio (March 2017). "Chemical composition, antioxidant activity and thermal analysis of oil extracted from favela ( Cnidoscolus quercifolius ) seeds". Industrial Crops and Products . 97 : 368–373. doi : 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.12.045 .

^ Pedro A. Pinto, Os Sertões de Euclides da Cunha : Vocabulário e Notas Lexiológicas , Rio: Francisco Al "Archived copy" . Archived from the original on 6 July 2011 . Retrieved 24 November 2010 . CS1 maint: archived copy as title ( link )

^ Aldeias do mal Archived 8 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine , MATTOS, Romulo Costa

^ Ney dos Santos Oliveira., "Favelas and Ghettos:race and Class in Rio de Janeiro

City"

^ Perlman, Janice (24 June 2010). Favela : Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro . USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195368369 .

^ Jump up to: a b Frisch, T. Glimpses of another world: The favela as a tourist attraction. February 2012.

^ Pino, Julio Cesar. Sources on the history of favelas in Brazil.

^ Balocco, André (18 November 2013). "Beltrame: 'Cabe lutar para manter as UPPs ' " . O Dia (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 November 2013 . Retrieved 11 December 2013 .

^ See Ronald Daus 's bibliography on Suburbs ( Free University of Berlin )

^ Jump up to: a b Mafra, Clara (March 2008). "Dwelling on the hill: Impressions of residents of two favelas in Rio de Janeiro regarding religion and public space". Religion . 38 (1): 68–76. doi : 10.1016/j.religion.2008.01.001 . S2CID 145068954 .

^ Brasil tem 11,4 milhões morando em favelas e ocupações, diz IBGE – GloboNews – Vídeos do Jornal GloboNews – Catálogo de Vídeos . G1.globo.com (21 December 2011).

^ IBGE: 6% da população brasileira vivia em favelas em 2010 Archived 24 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine . Tribuna do Norte.

^ Notícias – Gazeta Online – Favelas concentram 6% da população brasileira, com 11 mi de habitantes Archived 24 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine . Gazetaonline.globo.com (21 December 2011).

^ Caulfield, Sueann; Chambers, Sarah; Putnam, Laura (2005). Honor, Status, and Law in Modern Latin America . Durham NC: Duke University Press. pp. 189–192. ISBN 0-8223-3587-5 .

^ "World's barriers: Rio de Janeiro" . BBC. 5 November 2009 . Retrieved 6 July 2021 .

^ Bruno, Cassio; Onofre, Renato (10 November 2012). "Liberdade política é reforçada com implantação das UPPs" . O Globo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 11 November 2012 . Retrieved 11 November 2012 .

^ "Brasil tem 16,27 milhões de pessoas em extrema pobreza, diz governo" (in Portuguese). G1. 5 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012 . Retrieved 23 December 2011 .

^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Perlman, Janice E. Favela : Four Decades Of Living On The Edge In Rio De Janeiro. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009

^ Perlman, Janice E,.2006.The Metamorphosis of Marginality: Four Generations in the Favelas of Rio de Janeiro. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science .606 Annals 154:2

^ Oliveira, Ney dos Santos.1996.Favelas and Ghettos: Race and Class in Rio de Janeiro and New York City. Latin American Perspectives 23:82.

^ The Myth of Personal Security: Criminal Gangs, Dispute Resolution, and Identity in Rio de Janeiro's Favelas. By: Arias, Enrique Desmond; Rodrigues, Corinne Davis. Latin American Politics & Society, Winter2006, Vol. 48 Issue 4, p 53–81, 29p.

^ Brazilian Army Caves in to Favela's Drug Dealers Archived 24 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine . Brazzilmag.com (14 March 2006).

^ IBGE: 6% da população brasileira vivia em favelas em 2010 – Article at JCNET

^ Jump up to: a b c d WILLIAMS, CLAIRE. "Ghettourism And Voyeurism, Or Challenging Stereotypes And Raising Consciousness? Literary And Non-Literary Forays Into The Favelas Of Rio De Janeiro." Bulletin Of Latin American Research 27.4 (2008): 483–500. Business Source Complete. Web. 8 Dec. 2013.

^ Jump up to: a b Moreno, Carolina. "Brazilian Funk Music: Rio De Janeiro's 'Music From The Favelas' Gains Acceptance (VIDEOS)." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 18 Dec. 2012. Web. 8 Dec. 2013.

^ "Doncaster man sets up music school in Rio shanty town" . ITV News . 28 July 2016 . Retrieved 30 January 2021 .

^ Jump up to: a b Manfred, R. Poverty tourism: theoretical reflections and empirical findings regarding an extraordinary form of tourism. September 2009.

^ Jump up to: a b c Anonymous. Favela tourism guides new hope. Washington Report on the Hemisphere. April 2011.

^ "Puerto Rico Represents Brazil for Fast Five" . Ramascreen. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012 . Retrieved 20 November 2011 .

^ "3% (TV Series 2016–2020) - IMDb" .

Wiki Loves Monuments: your chance to support Russian cultural heritage!

Photograph a monument and win!

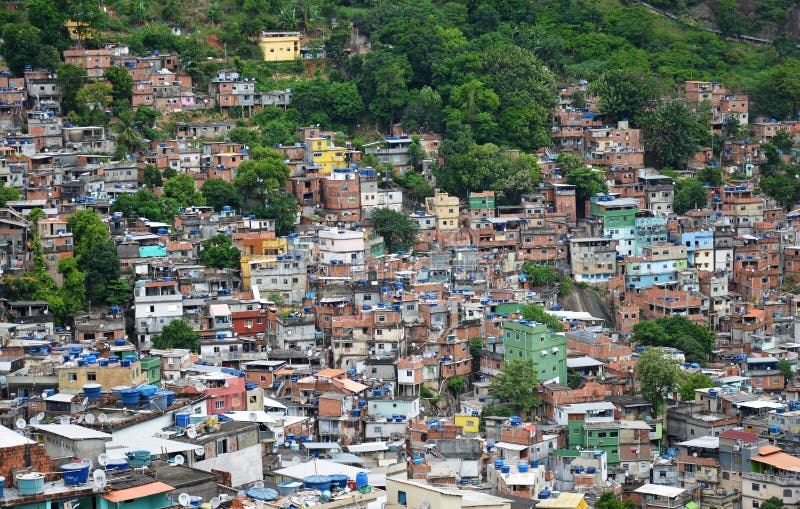

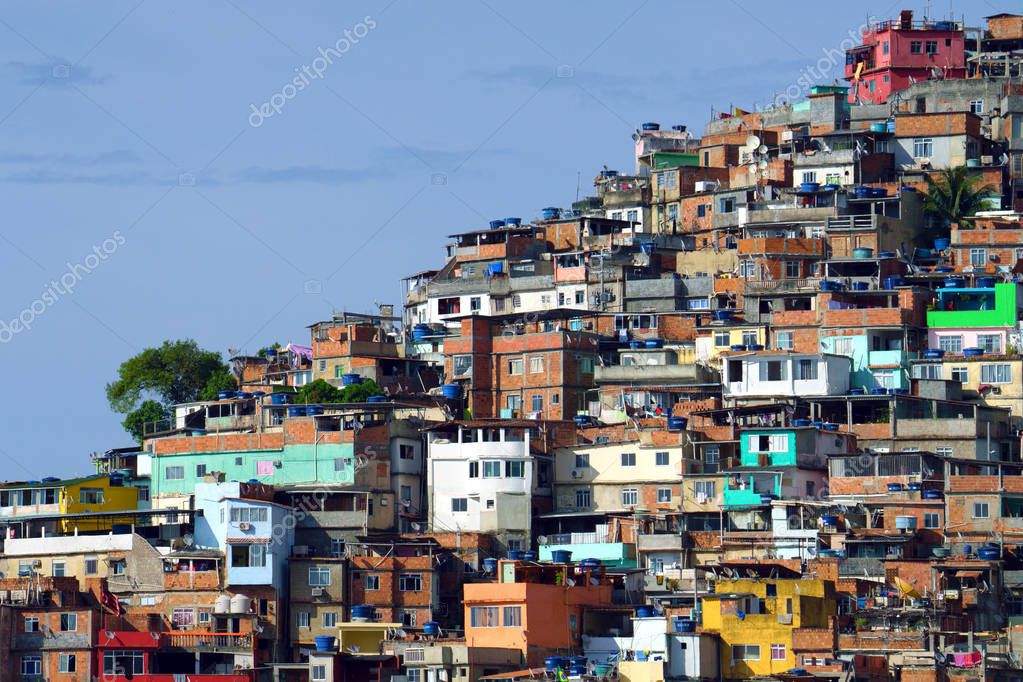

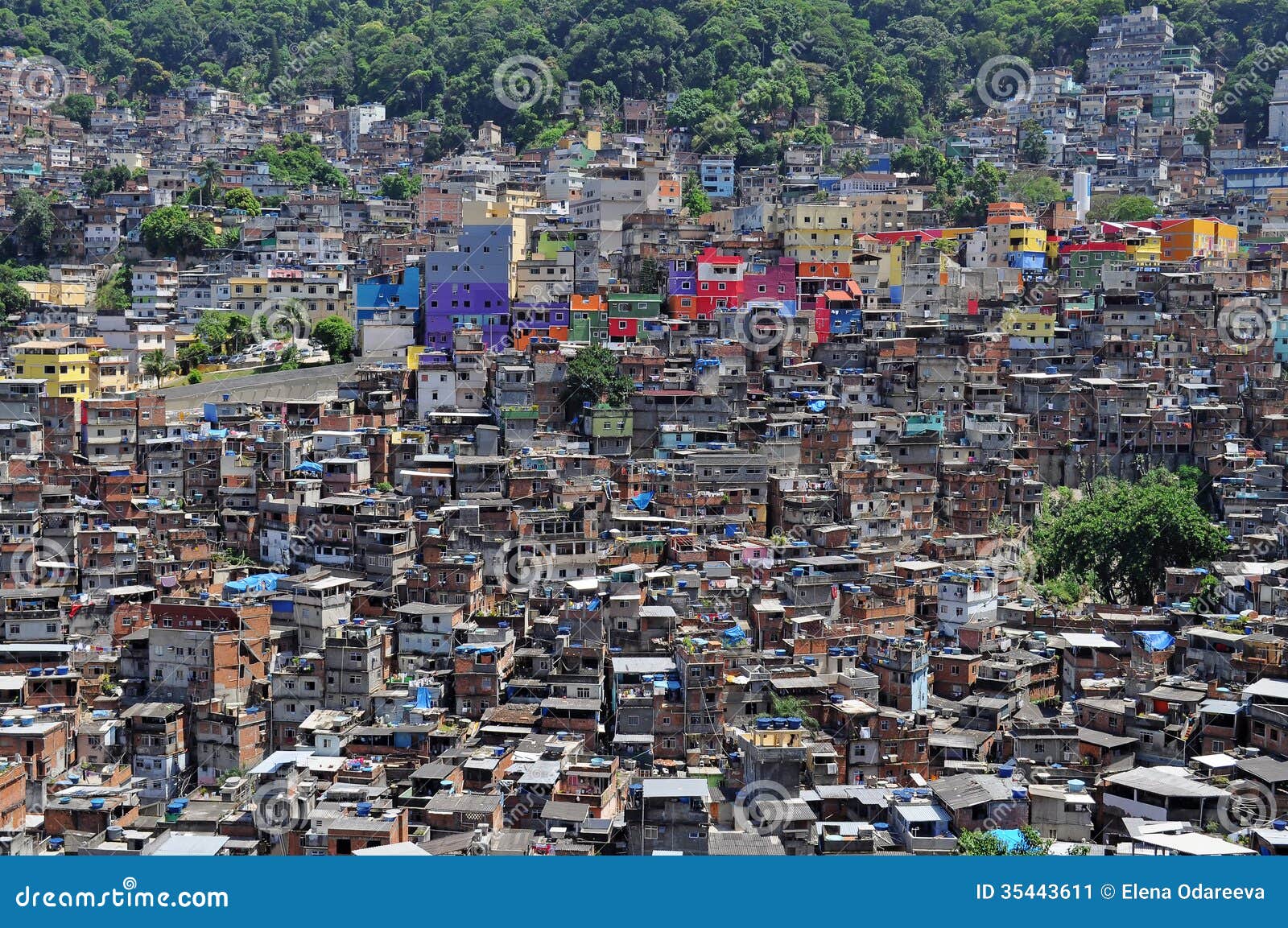

A favela ( Portuguese pronunciation: [fɐˈvɛlɐ] ) is a type of slum in Brazil that has experienced historical governmental neglect. The first favela, now known as Providência in the center of Rio de Janeiro, appeared in the late 19th century, built by soldiers who had nowhere to live following the Canudos War . Some of the first settlements were called bairros africanos (African neighborhoods). Over the years, many former enslaved Africans moved in. Even before the first favela came into being, poor citizens were pushed away from the city and forced to live in the far suburbs. Most modern favelas appeared in the 1970s due to rural exodus , when many people left rural areas of Brazil and moved to cities. Unable to find places to live, many people found themselves in favelas. [1] Census data released in December 2011 by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) showed that in 2010, about 6 percent of the Brazilian population lived in favelas and other slums. Favelas are located in 323 of the 5,565 Brazilian municipalities . [2] [3]

The term favela dates back to the late 1800s. [4] At the time, soldiers were brought from the conflict against the settlers of Canudos , in the Eastern province of Bahia , to Rio de Janeiro and left with no place to live. [5] When they served the army in Bahia, those soldiers had been familiar with Canudos' Favela Hill – a name referring to favela , a skin-irritating tree in the spurge family ( Cnidoscolus quercifolius ) indigenous to Bahia. [6] [7] [8] When they settled on the Providência [Providence] hill in Rio de Janeiro, they nicknamed the place Favela hill." [9]

The favelas were formed prior to the dense occupation of cities and the domination of real estate interests. [10] Following the end of slavery and increased urbanization into Latin America cities, a lot of people from the Brazilian countryside moved to Rio. These new migrants sought work in the city but with little to no money, they could not afford urban housing. [11] In the 1920s the favelas grew to such an extent that they were perceived as a problem for the whole society. At the same time the term favela underwent a first institutionalization by becoming a local category for the settlements of the urban poor on hills. However, it was not until 1937 that the favela actually became central to public attention, when the Building Code (Código de Obras) first recognized their very existence in an official document and thus marked the beginning of explicit favela policies. [12] The housing crisis of the 1940s forced the urban poor to erect hundreds of shantytowns in the suburbs, when favelas replaced tenements as the main type of residence for destitute Cariocas (residents of Rio). The explosive era of favela growth dates from the 1940s, when Getúlio Vargas 's industrialization drive pulled hundreds of thousands of migrants into the former Federal District, to the 1970s, when shantytowns expanded beyond urban Rio and into the metropolitan periphery. [13]

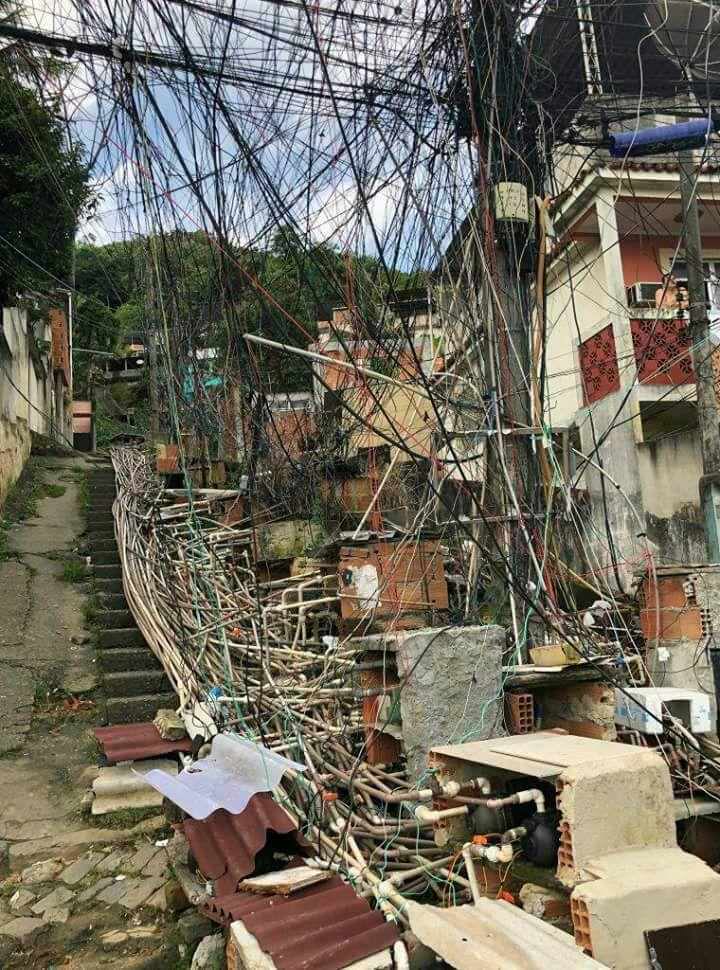

Urbanization in the 1950s provoked mass migration from the countryside to the cities throughout Brazil by those hoping to take advantage of the economic opportunities urban life provided. Those who moved to Rio de Janeiro chose an inopportune time. The change of Brazil's capital from Rio to Brasília in 1960 marked a slow but steady decline for the former, as industry and employment options began to dry up. Unable to find work, and therefore unable to afford housing within the city limits, these new migrants remained in the favelas. Despite their proximity to urban Rio de Janeiro , the city did not extend sanitation, electricity, or other services to the favelas. They soon became associated with extreme poverty and were considered a headache to many citizens and politicians within Rio. In the 1970s, Brazil's military dictatorship pioneered a favela eradication policy, which forced the displacement of hundreds of thousands of residents. During Carlos Lacerda 's administration, many were moved to public housing projects such as Cidade de Deus ("City of God"), later popularized in a wildly popular feature film of the same name. Poor public planning and insufficient investment by the government led to the disintegration of these projects into new favelas. By the 1980s, worries about eviction and eradication were beginning to give way to violence associated with the burgeoning drug trade. Changing routes of production and consumption meant that Rio de Janeiro found itself as a transit point for cocaine destined for Europe. Although drugs brought in money, they also accompanied the rise of the small arms trade and of gangs competing for dominance.

While there are Rio favelas which are still essentially ruled by drug traffickers or by organized crime groups called milícias ( Brazilian police militias ), all of the favelas in Rio's South Zone and key favelas in the North Zone are now managed by Pacifying Police Units , known as UPPs. While drug dealing, sporadic gun fights, and residual control from drug lords remain in certain areas, Rio's political leaders point out that the UPP is a new paradigm after decades without a government presence in these areas. [14]

Most of the current favelas really expanded in the 1970s, as a construction boom in the more affluent districts of Rio de Janeiro initiated a rural exodus of workers from poorer states in Brazil. Since then, favelas have been created under different terms but with similar results. [15]

Communities form in favelas over time and often develop an array of social and religious organizations and forming associations to obtain such services as running water and electricity. Sometimes the residents manage to gain title to the land and then are able to improve their homes. Because of crowding, unsanitary conditions, poor nutrition and pollution, disease is rampant in the poorer favelas and infant mortality rates are high. In addition, favelas situated on hillsides are often at risk from flooding and landslides. [16]

In the late 19th century, the state gave regulatory impetus for the creation of Rio de Janeiro's first squatter settlement. The soldiers from the War of Canudos (1896-7) were granted permission by Ministry of War to settle on the Providência hill, located between the seaside and centre of the city (Pino 1997). The arrival of former black slaves expanded this settlement and the hill became known as Morro de Providência (Pino 1997). The first wave of formal government intervention was in direct response to the overcrowding and outbreak of disease in Providência and the surrounding slums that had begun to appear through internal migration (Oliveira 1996). The simultaneous immigration of White Europeans to the city in this period generated strong demand for housing near the water and the government responded by "razing" the slums and relocating the slum dwellers to Rio's north and south zones (Oliveira 1996, pp. 74). This was the beginning of almost a century of aggressive eradication policies that characterised state-sanctioned interventions.

Favelas in the early twentieth century were considered breeding grounds for anti-social behavior and spreading of disease. The issue of honor pertaining to legal issues was not even considered for residents of the favelas. After a series of comments and events in the neighborhood of Morro da Cyprianna, during which a local woman Elvira Rodrigues Marques was slandered, the Marques family took it to court. This is a significant change in what the public considered the norm for favela residents, who the upper classes considered devoid of honor all together. [20]

Following the initial forced relocation, favelas were left largely untouched by the government until the 1940s. During this period politicians, under the auspice of national industrialisation and poverty alleviation, pushed for high density public housing as an alternative to the favelas (Skidmore 2010). The "Parque Proletário" program relocated favelados to nearby temporary housing while land was cleared for the construction of permanent housing units (Skidmore 2010). In spite of the political assertions of Rio's Mayor Henrique Dodsworth, the new public housing estates were never built and the once-temporary housing alternatives began to grow into new and larger favelas (Oliveira 1996). Skidmore (2010) argues that "Parque Proletário" was the basis for the intensified eradication policy of the 1960s and 1970s.

The mass urban migration to Rio de Janeiro in the 1950s resulted in the proliferation of favelas across the urban terrain. In order to deal with the "favela problem" (Portes 1979, pp. 5), the state implemented a full-scale favela removal program in the 1960s and 1970s that resettled favelados to the periphery of the city (Oliveira 1996). According to Anthony (2013), some of the most brutal favela removals in Rio de Janeiro's history occurred during this period. The military regime of the time provided limited resources to support the transition and favelados struggled to adapt to their new environments that were effectively ostracised communities of poorly built housing, inadequate infrastructure and lacking in public transport connections (Portes 1979). Perlman (2006) points to the state's failure in appropriately managing the favelas as the main reason for the rampant violence, drugs and gang problems that ensued in the communities in the following years. The creation of BOPE (Special Police Operations Battalion) in 1978 was the government's response to this violence (Pino 1997). BOPE, in their all black military ensemble and weaponry, was Rio's attempt to confront violence with an equally opposing entity.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, public policy shifted from eradication to preservation and upgrading of the favelas. The "Favela-Bairro" program, launched in 1993, sought to improve living standards for the favelados (Pamuk and Cavallieri 1998). The program provided basic sanitation services and social services, connected favelas to the formal urban community through a series of street connections and public spaces and legalised land tenure (Pamuk and Cavallieri 1998). Aggressive intervention, however, did not entirely disappear from the public agenda. Stray-bullet killings, drug gangs and general violence were escalating in the favelas and from 1995 to mid-1995, the state approved a joint army-police intervention called "Operação Rio" (Human Rights Watch 1996). "Operação Rio" was the state's attempt to regain control of the favelas from the drug factions that were consolidating the social and political vacuum left by previously unsuccessful state policies and interventions (Perlman 2006).

Since 2009, Rio de Janeiro has had walls separating the rich neighborhoods from the favelas, officially to protect the natural environment, but critics charge that it the barriers are for economic segregation. [21]

Beginning in 2008, Pacifying Police Units ( Portuguese : Unidade de Polícia Pacificadora , also translated as Police Pacification Unit), abbreviated UPP , began to be implemented within various favelas in the city of Rio de Janeiro. The UPP is a law enforcement and social services program aimed at reclaiming territories controlled by drug traffickers. The program was spearheaded by State Public Security Secretary José Mariano Beltrame with the backing of Rio Governor Sérgio Cabral .

Rio de Janeiro's state governor, Sérgio Cabral, traveled to Colombia in 2007 in order to observe public security improvements enacted in the country under Colombian President Álvaro Uribe since 2000. Following his return, he secured US$1.7 billion for the express purpose of security improvement in Rio, particularly in the favelas. In 2008, the state government unveiled a new police force whose rough translation is Pacifying Police Unit (UPP). Recruits receive special training as well as a US$300 monthly bonus. By October 2012, UPPs have been established in 28 favelas, with the stated goal of Rio's government to install 40 UPPs by 2014.

The establishment of a UPP within a favela is initially

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Favela

https://library.brown.edu/create/fivecenturiesofchange/chapters/chapter-9/favelas-in-rio-de-janeiro-past-and-present/

Boy Spanking Punishment

Mature Deepthroat Tube

Granny Retro Incest

Favela - Wikipedia

Favelas in Rio de Janeiro, Past and Present | Brazil: Five ...

Brazilian favelas - YouTube

What’s it like to live in a Brazilian favela? - MSN

‘Stop killing us’: Rio favela residents demand answers ...

Brazil drug raid: 25 killed in Rio de Janeiro favela - CNN

FEEL BRAZIL: Favela! | ВКонтакте

In Pictures: Crackdown in Brazil’s favelas | Gallery | Al ...

Funk carioca - Wikipedia

Favela - Wikipedia

Brazilian Favela