Black House Slave

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

A house slave was a slave who worked, and often lived, in the house of the slave-owner, performing domestic labor. House slaves had many duties such as cooking, cleaning, being used as a sexual slave, serving meals, and caring for children.

In classical antiquity, many civilizations had house slaves.

The study of slavery in Ancient Greece remains a complex subject, in part because of the many different levels of servility, from traditional chattel slave through various forms of serfdom, such as Helots, Penestai, and several other classes of non-citizen.

Athens had various categories of slave, such as:

Houseborn slaves (oikogeneis) often constituted a privileged class. They were, for example, entrusted to take the children to school; they were "pedagogues" in the first sense of the term.[1] Some of them were the offspring of the master of the house, but in most cities, notably Athens, a child inherited the status of its mother.[2]

It appears that the Greeks did not breed their slaves, at least during the Classical Era, though the proportion of house born slaves appears to have been rather large in Ptolemaic Egypt and in manumission inscriptions at Delphi.[3] Sometimes the cause of this was natural; mines, for instance, were exclusively a male domain.

Also known as a writer of Socratic dialogues, Xenophon advised that male and female slaves should be lodged separately, that "… nor children born and bred by our domestics without our knowledge and consent—no unimportant matter, since, if the act of rearing children tends to make good servants still more loyally disposed, cohabiting but sharpens ingenuity for mischief in the bad."[4] The explanation is perhaps economic; even a skilled slave was cheap,[5] so it may have been cheaper to purchase a slave than to raise one.[6] Additionally, childbirth placed the slave-mother's life at risk, and the baby was not guaranteed to survive to adulthood.[2]

A house slave appears in the Socratic dialogue, Meno, which was written by Plato. In the beginning of the dialogue, the slave's master, Meo, fails to benefit from Socratic teaching, and reveals himself to be intellectually savage. Socrates turns to the house-slave, who is a boy ignorant of geometry. The boy acknowledges his ignorance and learns from his mistakes and finally establishes a proof of the desired geometric theorem. This is another example of the slave appearing more clever than his master, a popular theme in Greek literature.

The comedies of Menander show how the Athenians preferred to view a house-slave: as an enterprising and unscrupulous rascal, who must use his wits to profit from his master, rescue him from his troubles, or gain him the girl of his dreams. We have most of these plays in translations by Plautus and Terence, suggesting that the Romans liked the same genre.

And the same sort of tale has not yet become extinct, as the popularity of Jeeves and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum attest.

House slaves existed in the New World.

In Haiti, before leading the Haitian revolution, Toussaint Louverture had been a house slave.

Toussaint is thought to have been born on the plantation of Bréda at Haut de Cap in Saint-Domingue, owned by the Comte de Noé and later managed by Bayon de Libertat.[7] Tradition says that he was driver and horse trainer on the plantation. His master freed him at age 33, when Toussaint married Suzanne.[8] He was a fervent Catholic, and a member of high degree of the Masonic Lodge of Saint-Domingue.[9][10] In 1790 slaves in the Plaine du Flowera rose in rebellion. Different forces coalesced under different leaders. Toussaint served with other leaders and rose in responsibility. On 4 April 1792, the French Legislative Assembly extended full rights of citizenship to free people of color or mulattoes (gens de couleur libres) and free blacks.

In many households, treatment of slaves varied with the slave's skin color. Darker-skinned slaves worked in the fields, while lighter-skinned house servants had comparatively better clothing, food and housing.[11] Referred to as "house negroes", they had a higher status and standard of living than a field slave or "field negro" who worked outdoors, often in harsh conditions.

As in President Thomas Jefferson's household, the presence of lighter-skinned slaves as household servants was not merely an issue of skin color. Sometimes planters used mixed-race slaves as house servants or favored artisans because they were their children or other relatives. Several of Jefferson's household slaves were possibly children of his father-in-law John Wayles and the enslaved woman Betty Hemings, who were inherited by Jefferson's wife upon her father's death. In turn Jefferson himself raped Betty and John Wayles's daughter Sally Hemings, the half-sister to Thomas Jefferson's wife. The Hemings children grew up to be closely involved in Jefferson's household staff activities. Two sons trained as carpenters. Three of his four surviving mixed-race children with Sally Hemings passed into white society as adults.[12]

The term "house negro" appears in print by 1711. On May 21 of that year, The Boston News-Letter ran an advertisement that "A Young House-Negro Wench of 19 Years of Age that speaks English to be Sold."[13] In a 1771 letter, a Maryland slave-owner compared the lives of his slaves to those of "house negroes" and "plantation negroes", refuting an accusation that his slaves were poorly fed by saying they were fed as well as "plantation negroes", though not as well as the "house negroes".[13][14] In 1807, a report of the African Institution of London described an incident in which an old woman was required to work in the field after she refused to throw salt-water and gunpowder on the wounds of other slaves who had been whipped. According to the report, she had previously enjoyed a favored status as a "house negro".[15]

Margaret Mitchell made use of the term to describe a slave named Pork in her famed 1936 Southern plantation fiction, Gone With the Wind.[16]

African-American activist Malcolm X commented on the cultural connotations and consequences of the term in his 1963 speech "Message to the Grass Roots", wherein he explained that during slavery there were two types of slaves: "house negroes" who worked in the master's house, and "field negroes" who performed outdoor manual labor. He characterized the house negro as having a better life than the field negro, and thus being unwilling to leave the plantation and potentially more likely to support existing power structures that favored whites over blacks. Malcolm X identified with the field negro.[17]

House negro has been used in the contemporary era as a pejorative term to compare a contemporary black person to such a slave. The term has been used to demean individuals,[18][19] in critiques of attitudes within the African-American community, especially against politically right-leaning African-Americans,[20] and as a borrowed term in contemporary social critique.[21]

In New Zealand in 2012, Hone Harawira, a Member of Parliament and leader of the socialist Mana Party, aroused controversy after referring to Maori MPs from the ruling New Zealand National Party as "little house niggers" during a heated debate on electricity privatisation, and its potential effect on Waitangi Tribunal claims.[22]

In June 2017, comedian Bill Maher used the term self-referentially during a live broadcast interview with US Senator Ben Sasse, saying "Work in the fields? Senator, I’m a house nigga [...]. It’s a joke!"[23] Maher apologized for the comment.[24]

In April 2018, Wisconsin State Senator Lena Taylor used the term during a dispute with a bank teller. When the teller refused to cash a check for which there were insufficient funds, Taylor called the teller a "house nigger". Both Taylor and the teller are African Americans.[25]

^ Carlier, p.203.

^ a b Garlan, p.58.

^ Garlan, p.59.

^ The Economist, IX. Trans H. G. Dakyns, accessed 16 May 2006.

^ Pritchett and Pippin, pp.276–281.

^ Garlan, p.58. Finley (1997), p.154–155 remains doubtful.

^ Bell, pp.59-60, 62

^ "Toussaint L’Ouverture", HyperHistory Archived 2010-03-28 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 27 Apr 2008

^ David Brion Davis, "He changed the New World", Review of Madison Smartt Bell's Toussaint Louverture: A Biography, The New York Review of Books, 31 May 2007, p. 55

^ "Toussaint Louverture: A Biography and Autobiography: Electronic Edition". University of North Carolina. Retrieved 22 August 2007.

^ Genovese (1967)

^ Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, New York: W.W. Norton, 2008

^ a b "House". Oxford English Dictionary. Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0). Oxford University Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-956383-8.

^ "Extracts from the Carroll Papers". Maryland Historical Magazine. Maryland Historical Society. XIV (2): 135. June 1919. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

^ Report of the Committee of the African Institution. London: William Phillips, George Yard, Lombard Street. 1807.

^ Mitchell, Margaret (1936). Gone With The Wind. Macmillan.

^ Malcolm X (1990) [1965]. George Breitman (ed.). Malcolm X Speaks. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. pp. 10–12. ISBN 0-8021-3213-8.

^ "Obama a 'house negro', says Al-Qaeda". Sydney Morning Herald. November 21, 2008.

^ "Black Group Condemns Cartoonist for Racist Strip About Condoleezza Rice". Project 21 press release. July 19, 2004.

^ James, Darryl. "The Bridge: In the House". Blacknla.com.

^ Roche, Kathi Roche. "The Secretary: Capitalism's House Nigger". Women's Liberation Movement on-line archival collection, Special Collections Library. Duke University.

^ Danya Levy; Kate Chapman (September 6, 2012). "Harawira's N-bomb directed at National MPs". Fairfax NZ.

^ "Bill Maher Drops the N-Word on 'Real Time,' Sen. Ben Sasse Laughs". thedailybeast.com. March 6, 2017.

^ Dave Itzkoff (June 3, 2017). "Bill Maher Apologizes for Use of Racial Slur on 'Real Time'". New York Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2017. Mr. Maher said: "Work in the fields? Senator, I'm a house nigger. No, it's a joke."

^ Dan O'Donnell. "State Sen. Lena Taylor Cited for Disorderly Conduct'".

Content is available under CC BY-SA 3.0 unless otherwise noted.

Humanities

Applied and social sciences magazines

House Slaves: An Overview

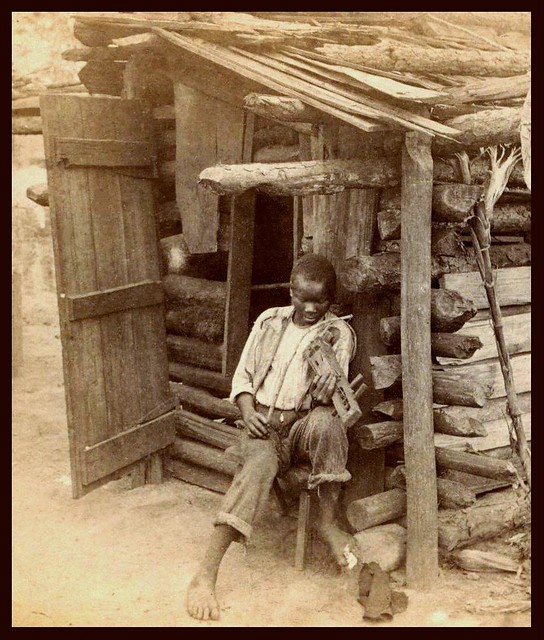

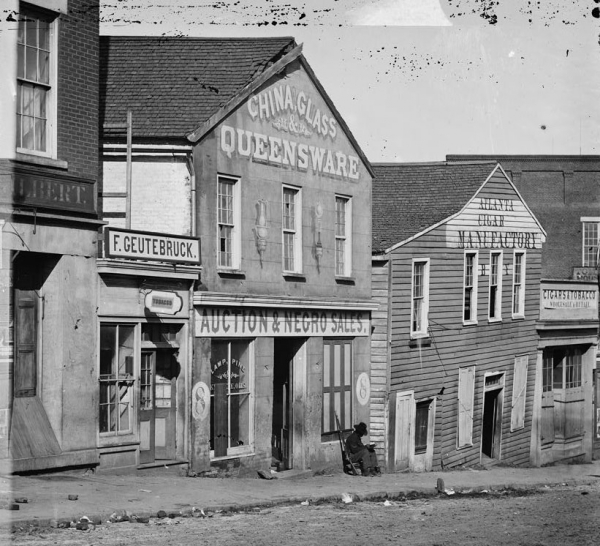

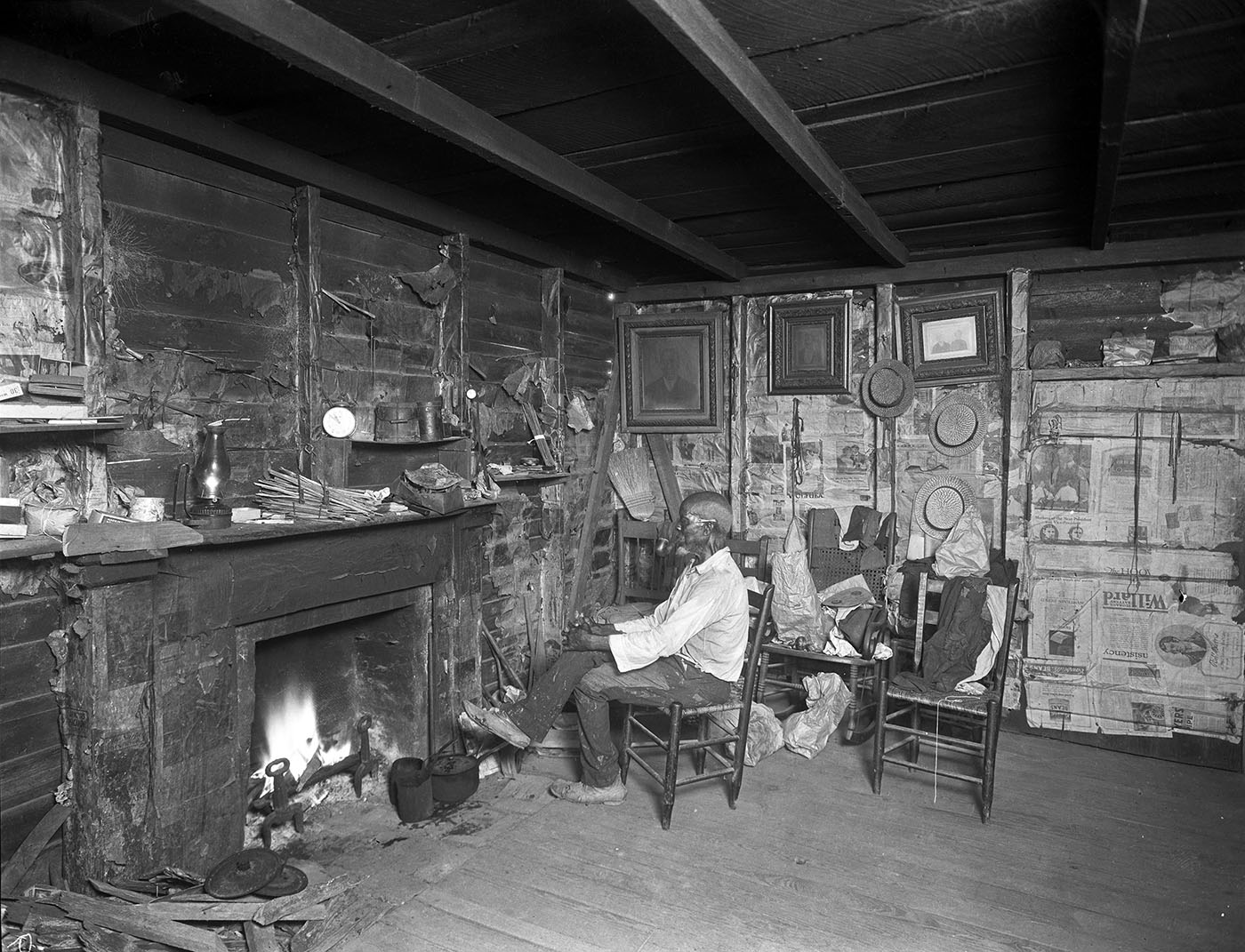

House slave was a term used to refer to those enslaved Africans relegated to performing domestic work on American slave plantations. Typically slave labor on the plantation was divided into two broad categories: house servants and field hands. The process of turning a person into a house servant or field hand was called "seasoning." The goal of seasoning was to socialize the enslaved into disciplined, obedient workers. The practice itself was coercive and extremely violent. The central task was to remove the cultural memory of those enslaved to ensure that notions of African inferiority and white superiority could replace it within three years (Phillips 1914, p. 546). It is estimated that close to 20 percent of those who reached American shores perished during the seasoning process (Society of Friends 1842, p. 19). During the seasoning process people were divided into three categories: New Africans or saltwater Negroes; Old Africans; and Creoles. New Africans or saltwater Negroes represented those recently from Africa. They spoke indigenous languages, carried African names, and maintained a strong connection to the culture of their ancestors. They were often considered the most dangerous and prone to rebellion. Old Africans were those who were born in Africa but spent a considerable amount of time within the plantation system. Typically they were middle-aged and elderly persons. Creoles were persons of African descent who were born in the Americas. Their social experiences were limited to the culture of American slave plantations. For the most part Creoles and Old Africans were preferred as house servants.

The vast majority of those enslaved were field hands. Field hands were the backbone of the plantation economy. They performed the most difficult agricultural tasks on cotton, sugar, rice, and tobacco plantations, which included: the clearing of forests for new farmland; the digging of irrigation ditches and construction of dikes for rice production; picking by hand the thorny cotton bush; and the manual planting and harvesting of sugarcane with a machete. As part of the gang labor system, field hands were often divided into work groups based upon age, physical health, and skill level. During the height of the growing season, field hands typically worked eighteen-hour days, from sunup to sundown. The regimentation of work on the plantation was critical for its profitability. Violence was the principle method used by overseers, drivers, and plantation owners to discipline field hands. Although the lifestyle of field hands varied from plantation to plantation, generally speaking they often lived in deplorable housing conditions, consumed the worst food, and received little if any medical attention. For this reason the lifespan of field hands was relatively short. Men, women, and children of all ages served as field hands. Pregnant women would often work in the fields until they delivered. Elderly men and women worked until they were disabled. The lifestyle of the field hand was backbreaking for most.

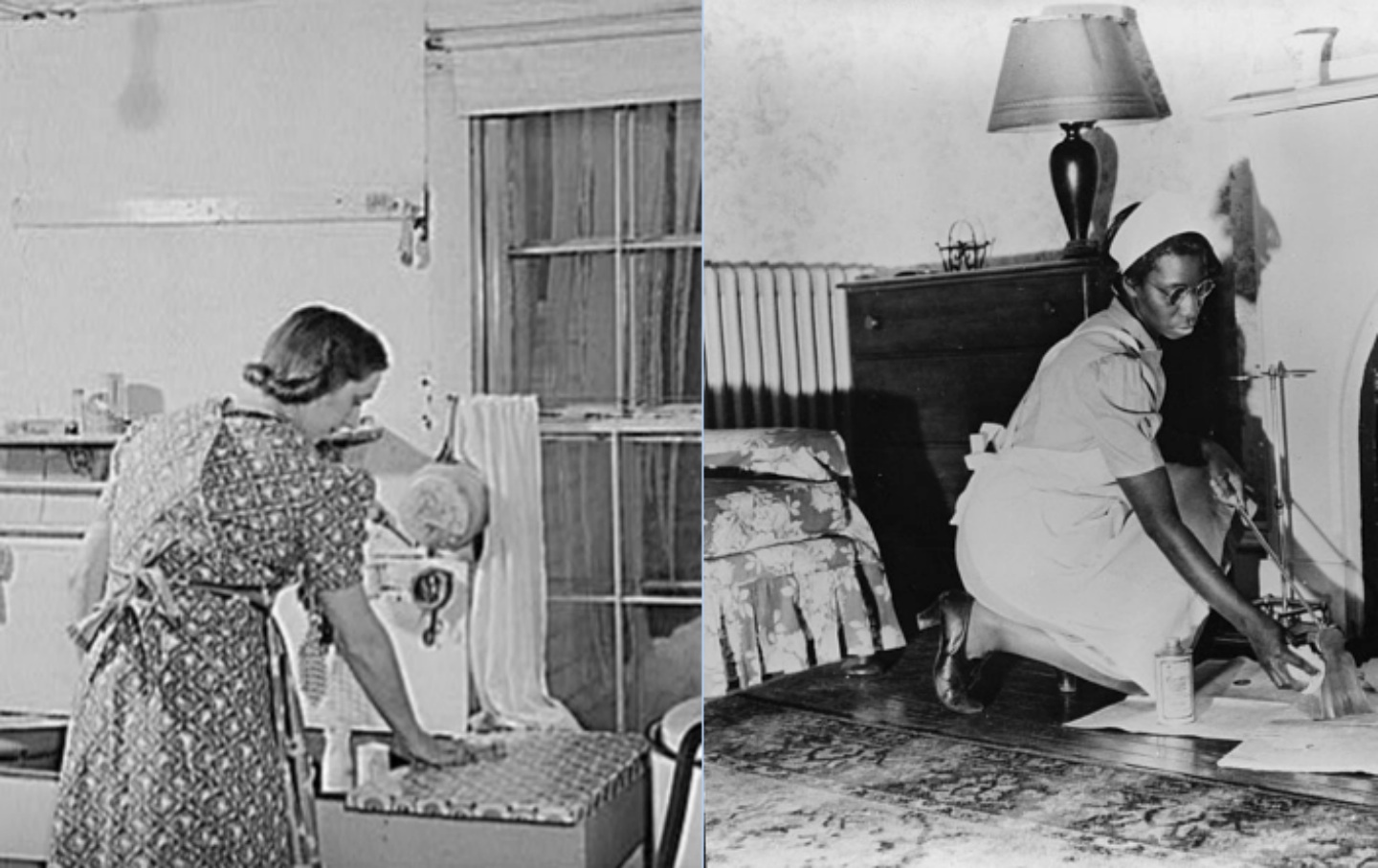

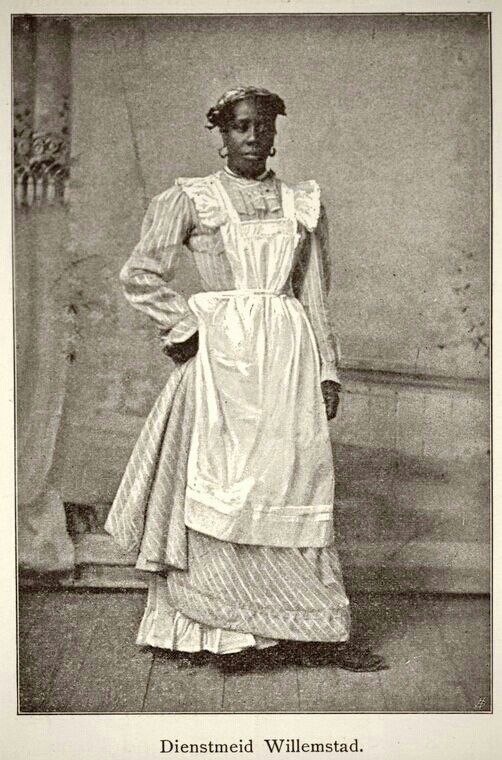

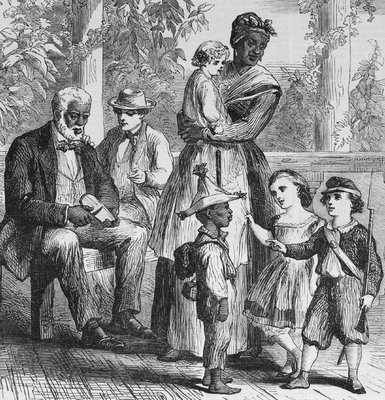

In stark contrast to the field hand was the life of the house slave. House slaves primarily performed tasks associated with maintaining the domestic life and home of the plantation owner. Typically this would include the following: cooking; cleaning; the maintenance of kitchen gardens for house consumption; running errands; caring for domestic animals; sewing and repairing clothes worn by the master's family; performing common household chores; and caring for the master's young children. The house slaves, although free from the backbreaking work of the field slaves, worked long hours as well. They were required to organize their entire lives around the social needs of the master's family. This was particularly true if there were young children. African American women, who served as domestic slaves, often performed the work of wet nurse and surrogate mother to newborns. Men would play a variety of roles including playmate and personal servant to adolescents as well as drivers. Drivers were essentially extensions of the overseer. They monitored the work of the field hands, disciplined the enslaved population through the use of violence, and participated in capturing runaways. Unlike field hands, house slaves were often given hand-me-downs from the master's family. In some cases instead of living in the slave quarters, they were given rooms in the master's home. Because they served as cooks they often consumed the leftovers from meals prepared for the master's family. Although learning how to read and write was illegal, many house servants learned from the wives and children of the plantation owner.

Differences between the work of house servants and field hands led to sharp social class distinctions within the plantation system. Socially speaking, house servants were considered a privileged class among the enslaved population. Because of their physical proximity to the home of the plantation owner, they often absorbed the culture and associated material benefits of the master (Ingraham 1860, pp. 34-36). The overseer, to control the behavior and work habits of the enslaved, used these divisions skillfully. Plantation owners who were disgruntled with their house servants would threaten to make these servants work out in the fields. Slave owners also made an attempt to ensure that house servants and field hands would remain socially isolated, both physically and psychologically, from one another even if they shared blood ties. House servants were threatened with flogging if they were caught interacting with field hands (Williams 1838, p. 48). In many ways, the notion of the happy house slave portrayed in movies such as Gone with the Wind, and the rebellious field slave are both mythic and simplistic. The lives and social consciousness of field hands and house servants were most often extremely complex.

The life of a house servant was often harsh and demeaning. Women house servants in particular were both desired and routinely raped by the plantation owner. Because they lived in close proximity to the master's family, the house servant was naturally absorbed into its many social conflicts. The master's desire for a slave mistress caused severe problems if he was married. In many cases the mistress of the house resented the presence of female house servants. Women house servants served as a constant reminder of marital infidelity. In response mistresses would often abuse their female house servants physically by slapping their faces, boxing their ears, and flogging. House servants were required to defer socially to the members of the master's family regardless of age differences. Elder men were required to refer to the teenage and adolescent children of the master as sir and ma'am. Elder women who often served as wet nurses for white infants were required to defer to them as adults (Jacobs 1861). In addition, house servants served as informants for the master and overseer, concerning the possibility of revolt by field hands. By the same token, house servants often performed the role of spy for field hands planning a rebellion. Being in close proximity to the master, they were privy to enormous amounts of information concerning the daily habits, hopes, fears, strengths, and weaknesses of the plantation system and its managers. This information would be vital to field hands who were planning an escape or a successful revolt. Although the nature of work performed by the house servant was much different from the work performed by the field hand, the overarching presence of the slave system and its coercive, violent, and humiliating methods of socialization invariably would define the lives of the enslaved regardless of their status within the plantation system.

Friends, Society of. New England Yearly Meeting. An Appeal to the Professors of Christianity in the Southern States and Elsewhere, on the Subject of Slavery. Providence, RI: Knowles and Vose, 1842.

Ingraham, Joseph Holt. The Sunny South, or, the Southerner at Home: Embracing Five Years' Experience of a Northern Governess in the Land of the Sugar and the Cotton. Philadelphia: G.G. Evans, 1860.

Jacobs, Harriet. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Boston: Published for the Author, 1861

Phillips, Ulrich Bonnell. "A Jamaica Slave Plantation" The American Historical Review vol. 19, no. 3 (April 1914): 543-558.

Williams, James. Narrative of James Williams, an American Slave: Who was for Several Years a Driver on a Cotton Plantation in Alabama. Boston, MA: Anti-Slavery Society, 1838.

Kwasi Densu

Licking Public Porno

Free Porn Full Movie Online

White Milf Huge Ass

Francis Belle Double Dicking Porn

Virus Xxx Sex Porn Hd

House slave - Wikipedia

House Slaves: An Overview | Encyclopedia.com

The Daily Life Of House Slaves from "Black Women In White ...

House of Slaves - Wikipedia

Sewell commission written by house slaves - Black Lives M…

29 Old slaves houses & other pictures ideas | abandoned ...

Slave Housing - Spartacus Educational

Black House Slave

%2c%2bvol_%2b42%2c%2bp_%2b552_%2b2.jpg)