Battle of Balaclava

Russian MFA

The Battle of Balaclava took place during the Crimean War between Great Britain, France and Turkey on one side, and the Russian Empire, on the other, on October 25, 1854. The battle became famous because of the four episodes that were made popular primarily by British publicists and painters. Despite a hard-fought confrontation, none of the sides achieved their goals in full. Read more about these events in our material.

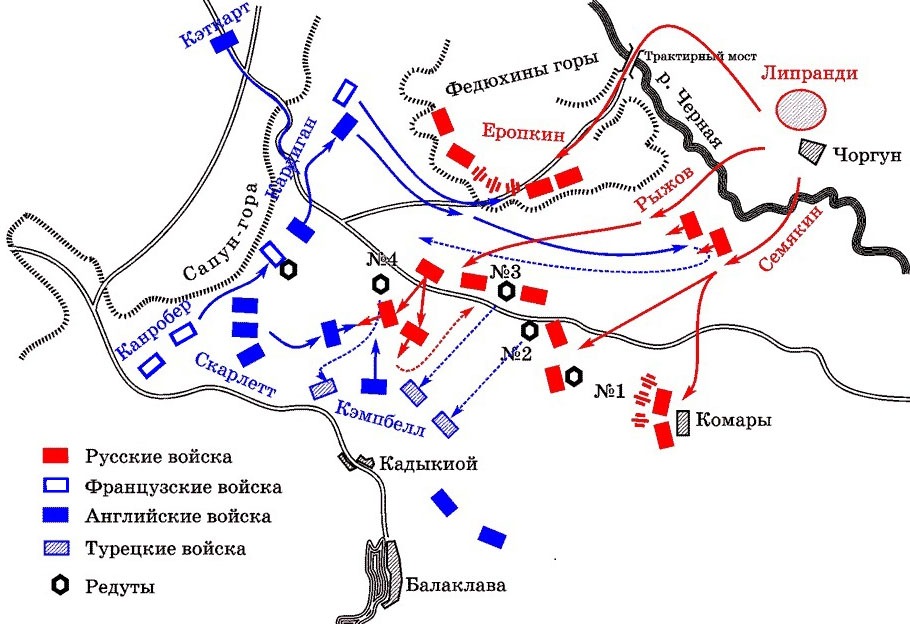

On September 27, 1854, taking advantage of their overwhelming superiority, the British army and navy took Balaclava which was defended by one Greek infantry battalion, after which they used the city as the main supply base for their army in Crimea, and they began preparations to assault Sevastopol. The joint forces of Great Britain, France and Turkey, 20,000 troops in all, built four defensive redoubts in the hills outside the occupied city.

In October 1854, the 16,000-strong army of the Russian Empire approached the Balaclava base. A successful attack could result in lifting the siege of Sevastopol, disrupting the supply chains of the united troops and changing the course of the Crimean War in favour of Russia.

The battle began before dawn at about 5 am. Russia used a bayonet attack to push the Turkish troops out of the first redoubt (No. 1 in the diagram) forcing the remaining three redoubts to be abandoned. The panic among the Turkish troops was such that the retreaters failed to disable the artillery in the redoubts, and the Russians took nine guns as a trophy. According to some accounts, the British soldiers tried unsuccessfully to stop the retreating Turks by shooting at them.

After the Turkish positions had been captured, the commander of the Russian army, Lieutenant-General Pavel Liprandi, used a hussar brigade in an attack to destroy the British artillery park, presumably abandoned in the lead up to the battle. However, having reached that position, Lieutenant-General Ryzhov, who led the attack, discovered a heavy British cavalry brigade at the camp site. The enemy was separated by a portion of a field tent camp, which was mistaken for the above artillery park.

According to various sources, the face-off came as a surprise to both sides due to the rugged terrain. After a fierce cavalry battle, the British retreated. But Ryzhov did not pursue the enemy and also had his cavalrymen fall back to their original position. According to contemporaries, after the war, he described this episode as follows: "It’s a rare occasion to see such cavalry masses fight with equal bitterness for such a long time. So, this battle should take its rightful place in the history of Russian cavalry."

During the battle between the two cavalry brigades, the 1st Ural Cossack Regiment led by Lieutenant-Colonel Horoshkhin approached the position held by the 93rd Scottish Infantry Regiment. Commander Baronet Campbell ordered the troops to line up in ranks of two to cover a wider front instead of ranks of four as prescribed by the rulebook. Campbell's order made it into British military history: "There will be no order to retreat, lads. You must die where you stand".

The Times correspondent described the Scottish regiment in historical materials about those events as “a thin red stripe bristling with steel.” Over time, this expression has become a fixed expression "the thin red line" meaning a last-ditch defence.

But despite the catchy name and a painting by Robert Gibb in 1881, there was no defence whatsoever, since the Cossacks turned around and retreated to their original positions 500 metres away from the Scots behind the rest of the cavalry due to the obvious futility of attacking an infantry that was ready for defence and covered by artillery and cavalry.

Fitzroy James Henry Somerset (1st Baron Raglan) could not reconcile himself to the loss of the guns earlier in the day, which was considered a disgrace, and issued a written order through Quartermaster Airey to George Charles Bingham (3rd Earl of Lucan) that read as follows: "Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front, to follow the enemy, and to try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop horse artillery may accompany. The French cavalry is on your left. Immediate. R. Airey". Bingham then ordered James Thomas Bradnell (7th Earl of Cardigan) to lead a brigade of over 600 men to attack the Russian positions in order to recapture the lost cannons. Bradnell tried to argue that they would be easy targets for Russian guns and riflemen, but Bingham replied that "we have no choice but to obey".

Despite the heavy losses caused by the hurricane-like fire of the Russian guns, the British managed to reach the Russian Army’s position, but General Ryzhov’s horsemen launched a counterattack and, after a fierce battle, forced the enemy to flee. The British had to retreat, as they actually found themselves in a fire pocket.

Somerset's pride cost the British 102 killed and 129 wounded soldiers (many of whom later died), and 58 taken prisoner. French General Pierre François Joseph Bosquet, who had come to the aid of the British cavalry and saved them from complete annihilation, was watching the attack and later said: "It's great, but it's not a war: it’s madness" (C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre: c'est de la folie).

Hiding the Bradnell brigade’s defeat was impossible, since it was an elite and fairly well-known formation, which lost dozens of offspring of noble families in just one battle. However, the British managed to portray it as a great feat and a triumph of military spirit and highlighted the courage, bravery and self-sacrifice of the cavalrymen rather than the fact of a deliberately failed attack attempt due to the pride and tyranny of the commander.

In total, according to various estimates, the joint forces lost anywhere from 500 to 600 soldiers killed or wounded during the battle and more than 150 were taken prisoners. The Russians also lost about 500 soldiers.

Unfortunately, despite the successful defeat of the attack, the capture of redoubts and the significant numerical superiority of the Russian Army, Pavel Liprandi was not victorious and ordered the troops to stop at the Fedyukhin Heights and the village of Komary, and then took them across the Chernaya River. Presumably, he feared that the enemy might soon receive reinforcements and cut his army off from Sevastopol.

Despite the fact that the Russian Army failed to defeat the English camp and sever the British troops’ supply chain, Pavel Liprandi’s successes foiled the original plans entertained by the joint troops of Great Britain, France and Turkey, who had to abandon the idea of capturing Sevastopol by assault and move on to positional siege operations, which subsequently played into the hands of the defenders of the city and influenced the further developments in the Crimean War.

#HistoryLessons #HistoryOfRussia #BattleOfBalaclava #CrimeanWar #RussianEmpire #GreatBritain #France #Turkey