Ancient Rome And Homosexuality

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Homosexuality in ancient Rome often differs markedly from the contemporary West. Latin lacks words that would precisely translate "homosexual" and "heterosexual".[1] The primary dichotomy of ancient Roman sexuality was active/dominant/masculine and passive/submissive/feminine. Roman society was patriarchal, and the freeborn male citizen possessed political liberty (libertas) and the right to rule both himself and his household (familia). "Virtue" (virtus) was seen as an active quality through which a man (vir) defined himself. The conquest mentality and "cult of virility" shaped same-sex relations. Roman men were free to enjoy sex with other males without a perceived loss of masculinity or social status, as long as they took the dominant or penetrative role. Acceptable male partners were slaves and former slaves, prostitutes, and entertainers, whose lifestyle placed them in the nebulous social realm of infamia, excluded from the normal protections accorded a citizen even if they were technically free. Although Roman men in general seem to have preferred youths between the ages of 12 and 20 as sexual partners, freeborn male minors were off limits at certain periods in Rome, though professional prostitutes and entertainers might remain sexually available well into adulthood.[2]

Same-sex relations among women are far less documented[3] and, if Roman writers are to be trusted, female homoeroticism may have been very rare, to the point that one poet in the Augustine era describes it as "unheard-of".[4] However, there is scattered evidence — for example, a couple of spells in the Greek Magical Papyri — which attests to the existence of individual women in Roman-ruled provinces in the later Imperial period who fell in love with members of the same sex.[5]

During the Republic, a Roman citizen's political liberty (libertas) was defined in part by the right to preserve his body from physical compulsion, including both corporal punishment and sexual abuse.[6] Roman society was patriarchal (see paterfamilias), and masculinity was premised on a capacity for governing oneself and others of lower status.[7] Virtus, "valor" as that which made a man most fully a man, was among the active virtues.[8] Sexual conquest was a common metaphor for imperialism in Roman discourse,[9] and the "conquest mentality" was part of a "cult of virility" that particularly shaped Roman homosexual practices.[10] Roman ideals of masculinity were thus premised on taking an active role that was also, as Craig A. Williams has noted, "the prime directive of masculine sexual behavior for Romans".[11] In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, scholars have tended to view expressions of Roman male sexuality in terms of a "penetrator-penetrated" binary model; that is, the proper way for a Roman male to seek sexual gratification was to insert his penis into his partner.[12] Allowing himself to be penetrated threatened his liberty as a free citizen as well as his sexual integrity.[13]

It was expected and socially acceptable for a freeborn Roman man to want sex with both female and male partners, as long as he took the penetrative role.[14] The morality of the behavior depended on the social standing of the partner, not gender per se. Both women and young men were considered normal objects of desire, but outside marriage a man was supposed to act on his desires with only slaves, prostitutes (who were often slaves), and the infames. Gender did not determine whether a sexual partner was acceptable, as long as a man's enjoyment did not encroach on another man's integrity. It was immoral to have sex with another freeborn man's wife, his marriageable daughter, his underage son, or with the man himself; sexual use of another man's slave was subject to the owner's permission. Lack of self-control, including in managing one's sex life, indicated that a man was incapable of governing others; too much indulgence in "low sensual pleasure" threatened to erode the elite male's identity as a cultured person.[15]

Homoerotic themes are introduced to Latin literature during a period of increasing Greek influence on Roman culture in the 2nd century BC. Greek cultural attitudes differed from those of the Romans primarily in idealizing eros between freeborn male citizens of equal status, though usually with a difference of age (see "Pederasty in ancient Greece"). An attachment to a male outside the family, seen as a positive influence among the Greeks, within Roman society threatened the authority of the paterfamilias.[16] Since Roman women were active in educating their sons and mingled with men socially, and women of the governing classes often continued to advise and influence their sons and husbands in political life, homosociality was not as pervasive in Rome as it had been in Classical Athens, where it is thought to have contributed to the particulars of pederastic culture.[17]

In the Imperial era, a perceived increase in passive homosexual behavior among free males was associated with anxieties about the subordination of political liberty to the emperor, and led to an increase in executions and corporal punishment.[18] The sexual license and decadence under the empire was seen as a contributing factor and symptom of the loss of the ideals of physical integrity (libertas) under the Republic.[19]

Love or desire between males is a very frequent theme in Roman literature. In the estimation of a modern scholar, Amy Richlin, out of the poems preserved to this day, those addressed by men to boys are as common as those they addressed to women.[20]

Among the works of Roman literature that can be read today, those of Plautus are the earliest to survive in full to modernity, and also the first to mention homosexuality. Their use to draw conclusions about Roman customs or morals, however, is controversial because these works are all based on Greek originals. However, Craig A. Williams defends such use of the works of Plautus. He notes that the homo- and heterosexual exploitation of slaves, to which there are so many references in Plautus' works, is rarely mentioned in Greek New Comedy, and that many of the puns that make such a reference (and Plautus' oeuvre, being comic, is full of them) are only possible in Latin, and can not therefore have been mere translations from the Greek.[21]

The consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus was among a circle of poets who made short, light Hellenistic poems fashionable. One of his few surviving fragments is a poem of desire addressed to a male with a Greek name.[22] In the view of Ramsay MacMullen, who is of the opinion that, before the flood of Greek influence, the Romans were against the practice of homosexuality, the elevation of Greek literature and art as models of expression promoted the celebration of homoeroticism as the mark of an urbane and sophisticated person.[23] The opposite view is sustained by Craig Williams, who is critical of Macmullen's discussion on Roman attitudes toward homosexuality:[24] he draws attention to the fact that Roman writers of love poetry gave their beloveds Greek pseudonyms no matter the sex of the beloved. Thus, the use of Greek names in homoerotic Roman poems does not mean that the Romans attributed a Greek origin to their homosexual practices or that homosexual love only appeared as a subject of poetic celebration among the Romans under the influence of the Greeks.[25]

References to homosexual desire or practice, in fact, also appear in Roman authors who wrote in literary styles seen as originally Roman, that is, where the influence of Greek fashions or styles is less likely. In an Atellan farce authored by Quintus Novius (a literary style seen as originally Roman), it is said by one of the characters that "everyone knows that a boy is superior to a woman"; the character goes on to list physical attributes, most of which denoting the onset of puberty, that mark boys when they are at their most attractive in the character's view.[26] Also remarked elsewhere in Novius' fragments is that the sexual use of boys ceases after "their butts become hairy".[27] A preference for smooth male bodies over hairy ones is also avowed elsewhere in Roman literature (e.g., in Ode 4.10 by Horace and in some epigrams by Martial or in the Priapeia), and was likely shared by most Roman men of the time.[28]

In a work of satires, another literary genre that Romans saw as their own,[29] Gaius Lucilius, a second-century BC poet, draws comparisons between anal sex with boys and vaginal sex with females; it is speculated that he may have written a whole chapter in one of his books with comparisons between lovers of both sexes, though nothing can be stated with certainty as what remains of his oeuvre are just fragments.[26]

In other satire, as well as in Martial's erotic and invective epigrams, at times boys' superiority over women is remarked (for example, in Juvenal 6). Other works in the genre (e.g., Juvenal 2 and 9, and one of Martial's satires) also give the impression that passive homosexuality was becoming a fad increasingly popular among Roman men of the first century AD, something which is the target of invective from the authors of the satires.[30] The practice itself, however, was perhaps not new, as over a hundred years before these authors, the dramatist Lucius Pomponius wrote a play, Prostibulum (The Prostitute), which today only exists in fragments, where the main character, a male prostitute, proclaims that he has sex with male clients also in the active position.[31]

"New poetry" introduced at the end of the 2nd century included that of Gaius Valerius Catullus, whose work include expressing desire for a freeborn youth explicitly named "Youth" (Iuventius).[32] The Latin name and freeborn status of the beloved subvert Roman tradition.[33] Catullus's contemporary Lucretius also recognizes the attraction of "boys"[34] (pueri, which can designate an acceptable submissive partner and not specifically age[35]). Homoerotic themes occur throughout the works of poets writing during the reign of Augustus, including elegies by Tibullus[36] and Propertius,[37] several Eclogues of Vergil, especially the second, and some poems by Horace. In the Aeneid, Vergil – who, according to a biography written by Suetonius, had a marked sexual preference for boys[38][39] – draws on the Greek tradition of pederasty in a military setting by portraying the love between Nisus and Euryalus,[40] whose military valor marks them as solidly Roman men (viri).[41] Vergil describes their love as pius, linking it to the supreme virtue of pietas as possessed by the hero Aeneas himself, and endorsing it as "honorable, dignified and connected to central Roman values".[42]

By the end of the Augustan period Ovid, Rome's leading literary figure, was alone among Roman figures in proposing a radically new agenda focused on love between men and women: making love with a woman is more enjoyable, he says, because unlike the forms of same-sex behavior permissible within Roman culture, the pleasure is mutual.[43] Even Ovid himself, however, did not claim exclusive heterosexuality[44] and he does include mythological treatments of homoeroticism in the Metamorphoses,[45] but Thomas Habinek has pointed out that the significance of Ovid's rupture of human erotics into categorical preferences has been obscured in the history of sexuality by a later heterosexual bias in Western culture.[46]

Several other Roman writers, however, expressed a bias in favor of males when sex or companionship with males and females were compared, including Juvenal, Lucian, Strato,[47] and the poet Martial, who often derided women as sexual partners and celebrated the charms of pueri.[48] In literature of the Imperial period, the Satyricon of Petronius is so permeated with the culture of male–male sex that in 18th-century European literary circles, his name became "a byword for homosexuality".[49]

Homosexuality appears with much less frequency in the visual art of Rome than in its literature.[50] Out of several hundred objects depicting images of sexual contact — from wall paintings and oil lamps to vessels of various types of material — only a small minority exhibits acts between males, and even fewer among females.[51]

Male homosexuality occasionally appears on vessels of numerous kinds, from cups and bottles made of expensive material such as silver and cameo glass to mass-produced and low-cost bowls made of Arretine pottery. This may be evidence that sexual relations between males had the acceptance not only of the elite, but was also openly celebrated or indulged in by the less illustrious,[52] as suggested also by ancient graffiti.[53]

When whole objects rather than mere fragments are unearthed, homoerotic scenes are usually found to share space with pictures of opposite-sex couples, which can be interpreted to mean that heterosexuality and homosexuality (or male homosexuality, in any case) are of equal value.[52][54] The Warren Cup (discussed below) is an exception among homoerotic objects: it shows only male couples and may have been produced in order to celebrate a world of exclusive homosexuality.[55]

The treatment given to the subject in such vessels is idealized and romantic, similar to that dispensed to heterosexuality. The artist's emphasis, regardless of the sex of the couple being depicted, lies in the mutual affection between the partners and the beauty of their bodies.[56]

Such a trend distinguishes Roman homoerotic art from that of the Greeks.[54] With some exceptions, Greek vase painting attributes desire and pleasure only to the active partner of homosexual encounters, the erastes, while the passive, or eromenos, seems physically unaroused and, at times, emotionally distant. It is now believed that this may be an artistic convention provoked by reluctance on the part of the Greeks to openly acknowledge that Greek males could enjoy taking on a "female" role in an erotic relationship;[57] reputation for such pleasure could have consequences to the future image of the former eromenos when he turned into an adult, and hinder his ability to participate in the socio-political life of the polis as a respectable citizen.[58] Because, among the Romans, normative homosexuality took place, not between freeborn males or social equals as among the Greeks, but between master and slave, client and prostitute or, in any case, between social superior and social inferior, Roman artists may paradoxically have felt more at ease than their Greek colleagues to portray mutual affection and desire between male couples.[56] This may also explain why anal penetration is seen more often in Roman homoerotic art than in its Greek counterpart, where non-penetrative intercourse predominates.[56]

A wealth of wall paintings of a sexual nature have been spotted in ruins of some Roman cities, notably Pompeii, where there were found the only examples known so far of Roman art depicting sexual congress between women. A frieze at a brothel annexed to the Suburban Baths,[59] in Pompeii, shows a series of sixteen sex scenes, three of which display homoerotic acts: a bisexual threesome with two men and a woman, intercourse by a female couple using a strap-on, and a foursome with two men and two women participating in homosexual anal sex, heterosexual fellatio, and homosexual cunnilingus.

Contrary to the art of the vessels discussed above, all sixteen images on the mural portray sexual acts considered unusual or debased according to Roman customs: e.g., female sexual domination of men, heterosexual oral sex, passive homosexuality by an adult man, lesbianism, and group sex. Therefore, their portrayal may have been intended to provide a source of ribald humor rather than sexual titillation to visitors of the building.[60]

Threesomes in Roman art typically show two men penetrating a woman, but one of the Suburban scenes has one man entering a woman from the rear while he in turn receives anal sex from a man standing behind him. This scenario is described also by Catullus, Carmen 56, who considers it humorous.[61] The man in the center may be a cinaedus, a male who liked to receive anal sex but who was also considered seductive to women.[62] Foursomes also appear in Roman art, typically with two men and two women, sometimes in same-sex pairings.[63]

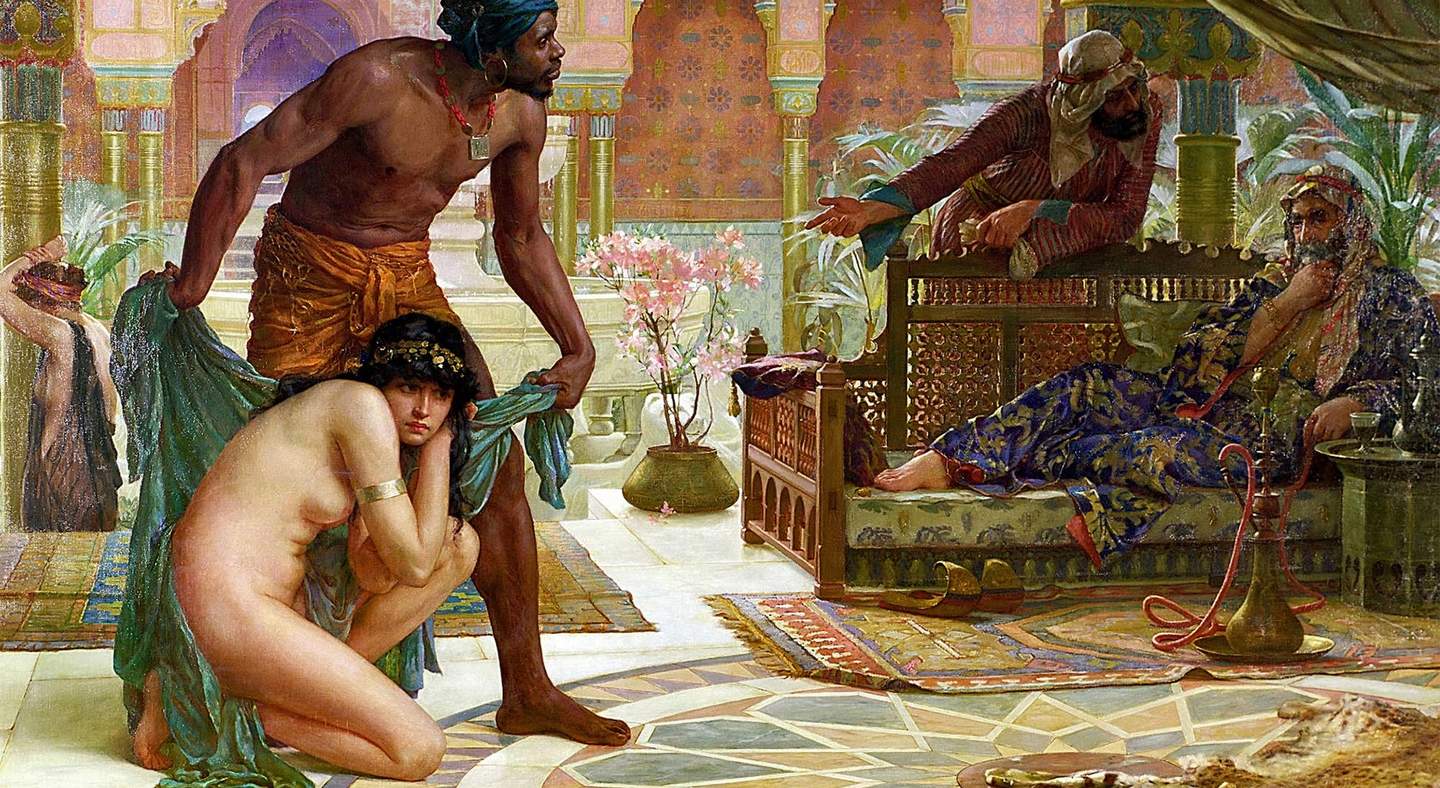

Roman attitudes toward male nudity differ from those of the ancient Greeks, who regarded idealized portrayals of the nude male. The wearing of the toga marked a Roman man as a free citizen.[64] Negative connotations of nudity include defeat in war, since captives were stripped, and slavery, since slaves for sale were often displayed naked.[65]

At the same time, the phallus was displayed ubiquitously in the form of the fascinum, a magic charm thought to ward off malevolent forces; it became a customary decoration, found widely in the ruins of Pompeii, especially in the form of wind chimes (tintinnabula).[66] The outsized phallus of the god Priapus may originally have served an apotropaic purpose, but in art it is frequently laughter-provoking or grotesque.[67] Hellenization, however, influenced the depiction of male nudity in Roman art, leading to more complex signification of the male body shown nude, partially nude, or costumed in a muscle cuirass.[68]

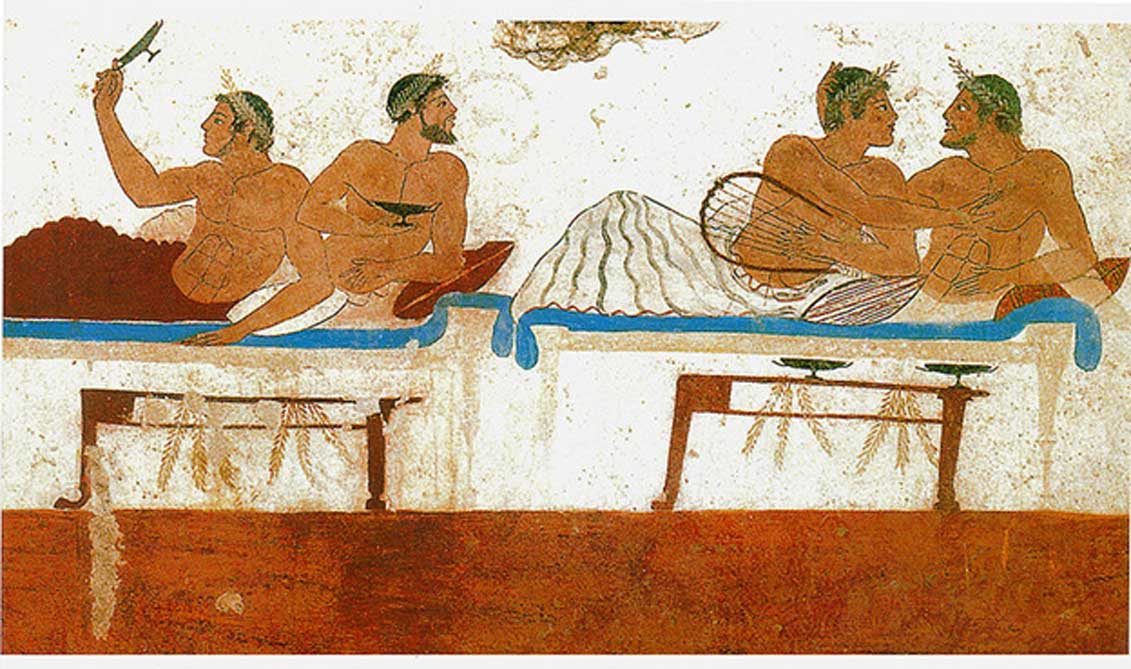

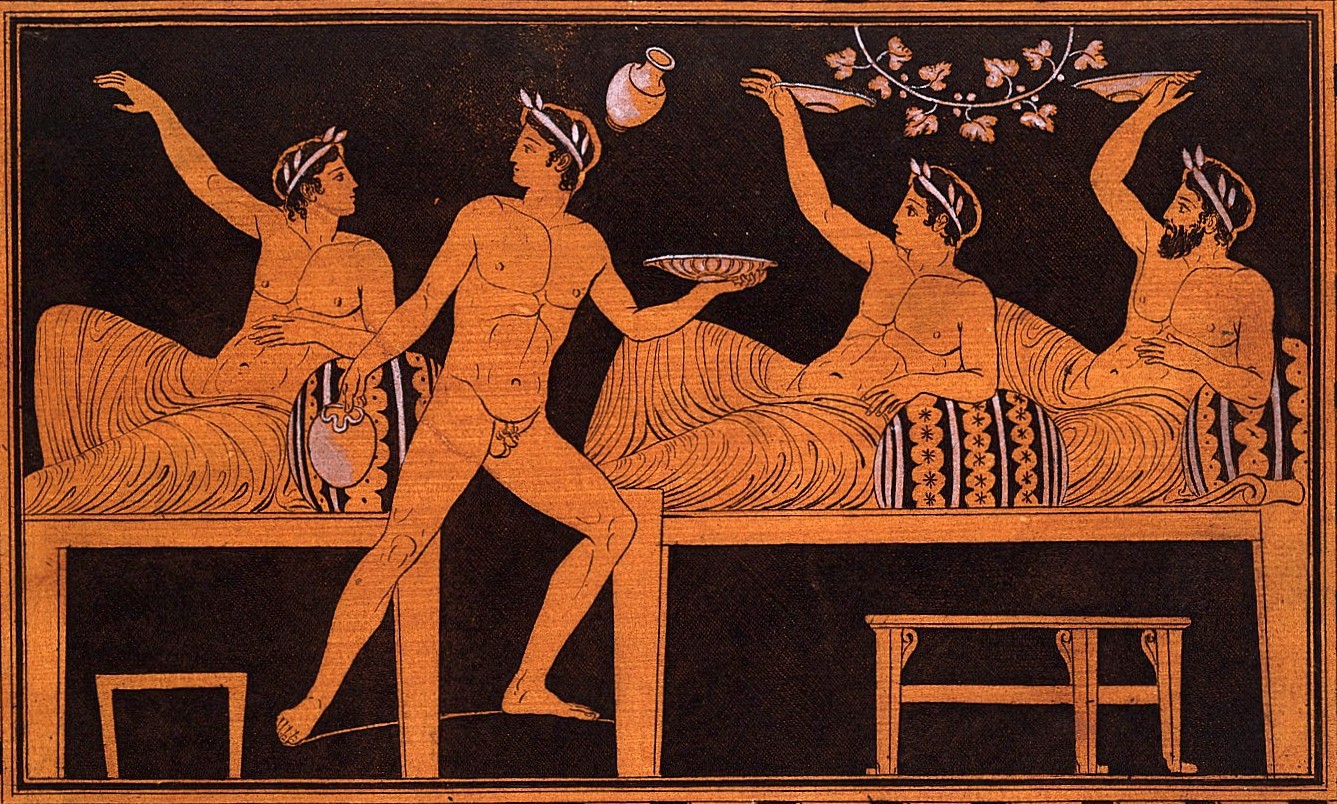

The Warren Cup is a piece of convivial silver, usually dated to the time of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (1st century AD), that depicts two scenes of male–male sex.[69] It has been argued[70] that the two sides of this cup represent the duality of pederastic tradition at Rome, the Greek in contrast to the Roman. On the "Greek" side, a bearded, mature man is penetrating a young but muscularly developed male in a rear-entry position. The young man, probably meant to be 17 or 18, holds on to a sexual apparatus for maintaining an otherwise awkward or uncomfortable sexual position. A child-slave watches the scene furtively through a door ajar. The "Roman" side of the cup shows a puer delicatus, age 12 to 13, held for intercourse in the arms of an older male, clean-shaven and fit. The bearded pederast may be Greek, with a partner who participates more freely and with a look of pleasure. His counterpart, who has a more severe haircut, appears to be Roman, and thus uses a slave boy; the myrtle wreath he wears symbolizes his role as an "erotic conqueror".[71] The cup may have been designed as a conversation piece to provoke the kind of dialogue on ideals of love and sex that took place at a Greek symposium.[72]

More recently, academic M. T. Marabini Moevs has questioned the authenticity of the cup, while others have published defenses of its authenticity. Marabini Moevs has argued, for example, that the Cup was probably manufactured by the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries and that it supposedly represents perceptions of Greco-Roman homosexuality from that time,[73] whereas defenders of the legitimacy of the cup have highlighted certain signs of ancient corrosion and the fact that a vessel manufactured in the 19th century, would have been made of pure silver, whereas the Warren Cup has a level of purity equal to that of other Roman vessels.[74] To address this issue, the British Museum, which holds the utensil, performed a chemical analysis in 2015 to determine the date of its production. The analysis concluded that the silverware was indeed made in classical antiquity.[75]

A man or boy who took the "receptive" role in sex was variously called cinaedus, pathicus, exoletus, concubinus (male concubine), spintria ("analist"), puer ("boy"), pullus ("chick"), pusio, delicatus (especially in the phrase puer delicatus, "exquisite" or "dainty boy"), mollis ("soft", used more generally as an aesthetic quality counter to aggressive masculinity), tener ("delicate"), debilis ("weak" or "disabled"), effeminatus, discinctus ("loose-belted"), pisciculi, spinthriae, and morbosus ("sick"). As Amy Richl

Homosexuality in Ancient Rome

Гомосексуализм в Древнем Риме - Homosexuality in ancient Rome - qaz.wiki

Was homosexuality accepted in ancient Rome? - Quora

What Sex Was Like in Ancient Rome | by Sal | Lessons from History | Medium

Homosexuality in Ancient Rome - YouTube

How To Tie Tits

Amatuer Gilf Porn

Nsa Slang

Ancient Rome And Homosexuality

_(detail)_900x1200.jpg)

630_.jpg" width="550" alt="Ancient Rome And Homosexuality" title="Ancient Rome And Homosexuality">

630_.jpg" width="550" alt="Ancient Rome And Homosexuality" title="Ancient Rome And Homosexuality">