An Artist’s Exhibition of Portraits from the Anti-ELAB movement

Translated by Guardians of Hong Kong

What made a painter put down his brush and take to the streets? Chow Chun Fai (Chow) and a few others from the arts and culture community formed an industrial buildings concern group. They met with Chief Executive Officer Carrie Lam. In order to challenge the sports, performing arts, culture and publication constituency LegCo councillor Ma Fung-Kwok, Chow put aside his art work for a year to run for the election. He took to the streets again on 12 June last year. "I always think art is too slow. It is quicker to write on a piece of black cloth with white paint. The anti-ELAB movement changed me."

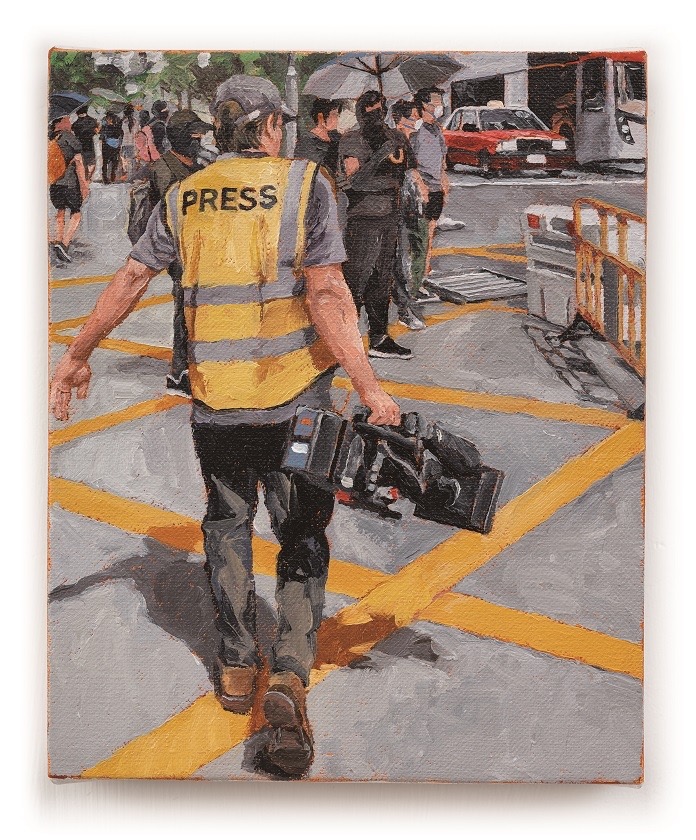

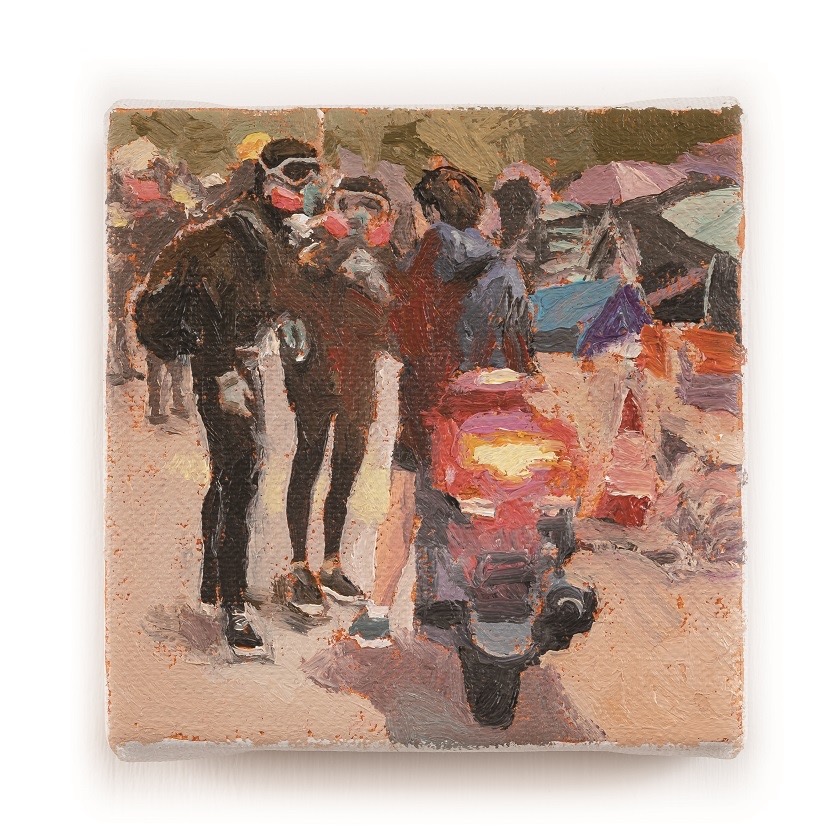

He drew the backs of individuals he saw on the streets during the movement. Despite this, the most memorable scenes were far beyond what his brushes and canvases could capture, yet they remain in his mind.

Paintings for Myself

"It is natural to not want any infringement of one’s creative freedom,” Chow mused. “If your goal is to climb the social ladder, there are other lines of work to choose from, it’s not necessary to go into creative arts.” In his most renowned series of artwork featuring films, he used the canvas to re-produce certain scenes from Hong Kong movies. These works contain political elements but he never directly used arts to express politics or any social movement before. The Portraits from Behind exhibition is his first direct recording of events from the anti-ELAB movement. He admitted that he feels differently now.

"In the past I tended to be more distant and rational but this time the topic is more communal, societal and even political. I have projected more of my emotions (in the current topic). I was more objective and indifferent when I drew the film arts. This time I have poured in my own feelings,” Chow said. "I used to think - why shouldn’t I use another method to express political messages? If I use white paint on black cloth to make banners, I can bring them to the streets. Why should I use canvas in these paintings?"

On 12 June last year when more than 10,000 people surrounded the Legislative Council building, Chow arrived early with his camera. When the riot police started to fire tear gas to disperse the crowds at noon, he got a taste of the it near City Hall. "I was quite calm in the beginning. It wasn’t dark yet and the police had already deployed tear gas. So I thought I better take some photos first. Soon the tear smoke drifted towards me and I couldn't see anything. I knew someone helped rinse my eyes, but by the time I could open my eyes again, those who helped me were gone.”

He only noticed his swollen ankles when he got home, he had sprained them earlier. Because of the injury, he did not join any protests for a while. During that period, he organised industrial actions. Sometimes, he went to those events with his crutches. He was not doing any artwork at the time anyway.

One day, he took out a small piece of canvas and started painting on a whim. “Exhibiting this work was not on my mind when I drew these. They were meant for myself. I never thought of showing them to the public. I just wanted to keep painting, I could not stop."

There were 60-70 new paintings hung up on two walls in his studio. Different protest scenes during a 6- month period of the movement were revived. "I did not think about showing them until Gallery EXIT approached me at the end of last year. Art Basel had not announced its cancellation at the time. In light of that, I just continued to paint.”

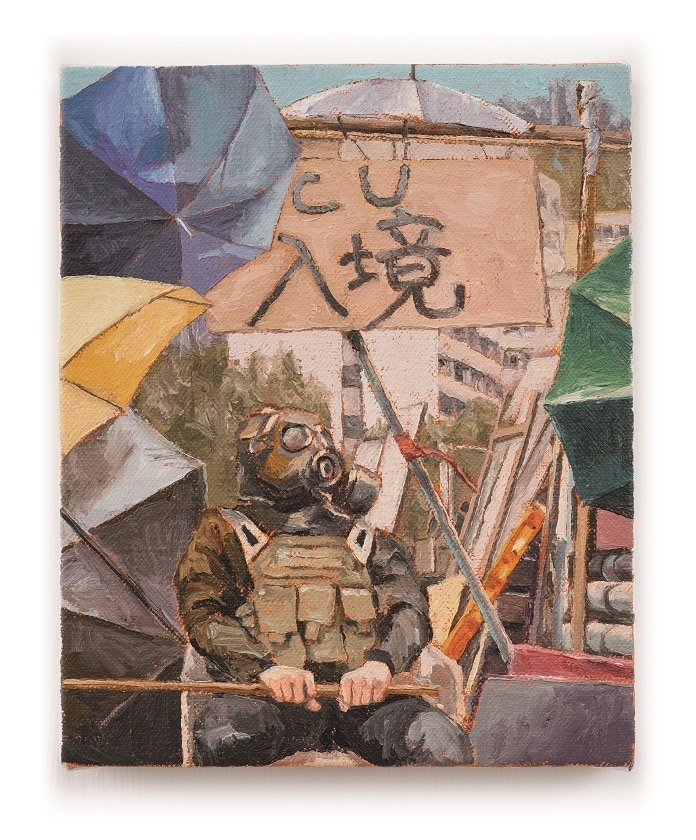

Not sure who they were

These paintings captured the street scenes of Hong Kong in 2019. They also recorded Chow's trails and his state of mind. "The portraits were small, I finished very quickly. I only took about 2 or 3 hours to complete one drawing. Yet as the situations developed rapidly, I had to draw another one every 2 or 3 days." The largest one he painted was the sit-in protest "Fly With You" at the airport. He started drawing this particular scene after deciding to have an exhibition. "I intentionally created smaller canvases to capture bigger and more violent incidents. The bigger canvases I used for peaceful, rational, non-violent protests. This was done to provide a sharp contrast. It is actually a kind of suppression. I spent much effort to paint the background at the airport. A lot of people participated in the event but it was very peaceful and orderly. I considered that the peaceful, rational, non-violent scenes represented the point of view accepted by more people in the society. On the other hand, those smoky and fiery conflict scenes were drawn on smaller canvases. With the different scenes, which ones do people find more acceptable? Most people would accept peaceful, rational, non-violent protests. The sit-in protest at the airport was very special. I am not sure if it is still possible in the future as the airport has closed (to people who don’t have valid air tickets)." A giant grey cement block at the top of the painting seems to be pressing on the crowds underneath. “It is rather static visually, but there is still movement.”

The details of the paintings highlighted the theme of the exhibition -- Portraits from Behind. "Throughout the movement people have helped each other, just like those people who rinsed my eyes on 12 June. We did not know each other personally. People also put on face masks to avoid being identified. Photos were not taken because people did not want to be seen. That’s why I drew their backs in my paintings." Chow drew a small portrait of a firefighter’s back in Yau Ma Tei on the night when the Hong Kong Polytechnic University was under siege.“ That night, shops were vandalised but I did not draw the shops." At the beginning, he brought his camera to the protest rallies. Later, he changed to smartphones. "I understand that sometimes it is inevitable to have quarrels with the frontline protesters. I have a friend who was arrested because somebody took photos of his car registration plate when he drove protesters home. He had to spend Chinese New Year in the detention centre.” The artist reflects upon himself while he creates the artwork. "I left a lot of my personal traits in these paintings."

His last exhibition in 2015 was called “I Have Nothing To Say” at Hanart TZ Gallery. Chow used a lot of modern art languages. It was more playful and flirtatious. By contrast, his work this time is less polished, a more direct display of raw emotions. It is back to basics. "Right, this time I painted without excessive planning. In the past, I took a long time to think before deciding what to put in the pictures to make them powerful. The movement itself is already very dramatic or even absurd! For example, fires set on bridges, vehicles and the trees in front of me. These combinations were unimaginable. Modern art puts meanings in the drawings. It is not necessary now.”

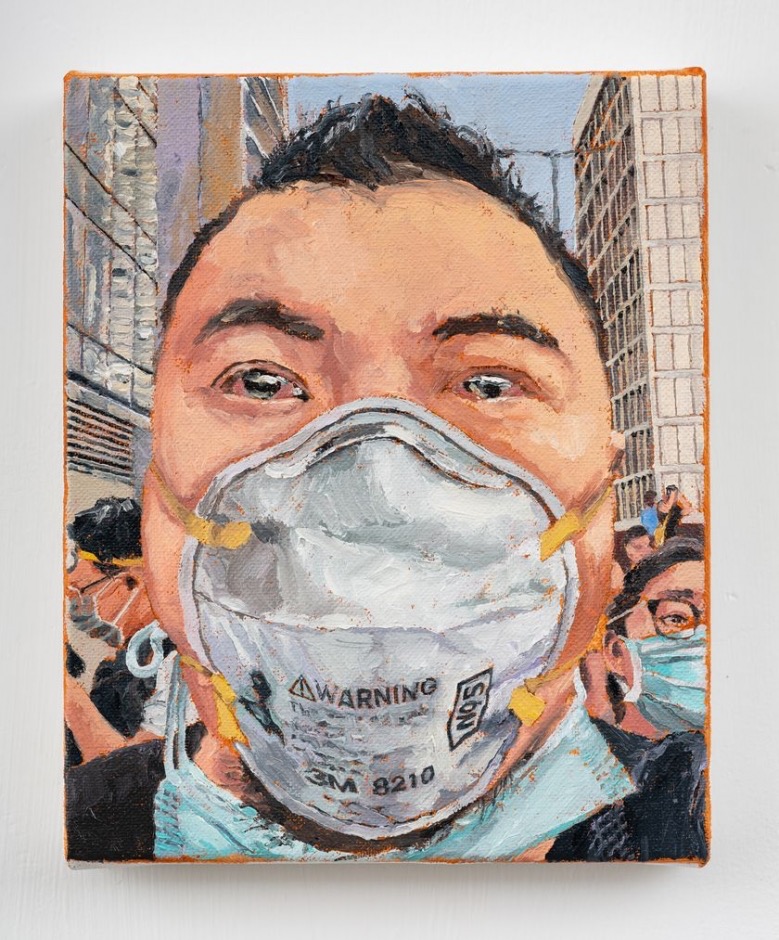

Paradoxically, these paintings are both paintings and records, but they are not purely records. There are two paintings that look like self portraits of Chow with a respirator on his face. I asked Chow whether it was him. He laughed, "I couldn’t tell you whether I was present at the scene. Canvas painting is the most direct form of record-keeping but because it is also a painting, it cannot be considered evidence of my presence at the sites." His work this time made him reflect on his own changes. "When we look at historical paintings in the museums, 99% of the time we don't understand the story behind them. Even though I studied arts, I still don't understand a lot of these paintings because I did not live in those situations! However, I could clearly remember the dates of the events in my pictures. Even so, I can quickly forget about them. If one day, we (protesters) could meet each other without our masks on, we may forget those scenes as well. Eventually we will depart from our current situation. Just like when we look at the scenes captured in those historical European paintings through the lens of our era!”

Arts can still last longer than life. "If we look for background information today, we can find the original power of these historical paintings. My paintings are the same. Even if you take a step back and try to wipe the movement off history books … when you look at the fires burning on the road, even foreigners can sense the intense power." In the past Chow always struggled with the thought that the power of arts was very limited. If we go back to basics, painters are humans after all. Sometimes when brushes cannot get the job done, they have to bring banners to the streets. My thought is different now. "The paradox about paintings is that their power could be greater years later.”

Taxi and Art

Chow has painted a lot but he could not draw his most unforgettable scenes. They are still in his heart. "I want to draw a few scenes but I did not record them in time. At least I didn't take the photos. I rode my bike to Chinese University on the day of the siege. The most impressive scenes for many people were the tear gas and bullets fired at No. 2 Bridge or the thick smoke billowing from the Sir Philip Haddon-Cave sports field. Yet my most memorable scene was riding along Tai Po Road, seeing supplies accumulating at the roundabouts; motorcycles and private cars circled around them. That was a very dramatic scene, an anarchic state, like it was from a movie. People would try to stop you along the way. They might want to hitch a ride or may be they wanted to pass you a lighter." Chow did not take photos of these scenes but they stayed in his heart. "Of course, I can create something with them. In the end, I only painted a small picture."

Chow's studio has always been in the Fo Tan industrial district. It is just opposite Chun Yeung Estate, a media spotlight (at the beginning of the outbreak). The public housing estate was urgently designated as a quarantine facility for passengers of the Diamond Princess vessel (in which there was an outbreak on board). "The estate was supposed to be ready for occupancy. Now it has become an epidemic screening centre. The government put barricades outside the site. The atmosphere suddenly tensed up."

Chow’s life always seems to be intertwined with Hong Kong’s changing social environment, political atmosphere and current affairs. These make him difficult to quiet down as a citizen and an artist. "I began to pay attention to politics when I formed the industrial building concern group in 2009. That year, the government was trying to revitalise industrial buildings. At that point, I figured I needed to do something about this, so I started preparing documents for submission to the government. Take the example of the public estate (Chun Yeung Estate), it was supposed to be built during the Donald Tsang era. We wrote to oppose it." Chow remembered the faces of those bureaucrats he met. "An official told me that it will be beneficial because tens of thousands of residents will move into the public estate, and they will become a new group of audience for our work. He also talked about building a civic centre inside the mall and basically framed it as a win-win situation."

Born in 1980, he enrolled as an arts student in the Chinese University.Since then, Chow has not miss out on any major events in Hong Kong . Chow’s dad became seriously ill after he bought a taxi license in 2001 when Chow just entered the university. Chow had to drive the taxi to support his studies in the second year. There are always taxis in his paintings. However, he is not emotionally attached to them. "I support Uber. I did not enjoy those days when I needed to pay the taxi loan." Taxi drivers work "12-hour shifts. No one knows where you’re going. Some people could rest when they made sufficient money. It all depends on you,” Chow said. The same could be said of an artist’s career. “Having freedom also means having self-discipline, no on will tell what you should be doing.” His self-discipline came from continuously creating. Chow had solo exhibitions in Italy and the USA in recent years. His paintings were put up at auction houses but he shows disdain for some mainland artists who set their goals based on the price of their work. "Some people aim to sell a certain price level before reaching a certain age. I find it disgusting. I am not trying to stand on moral high ground. It’s just that if I had such mentality, I would not have chosen creative arts. Some people set a timeframe for when they will start having biennial exhibitions. In mainland they regard this as ‘trendy’. It is meaningless to me."

Pro-Establishment collectors felt betrayed

Chow's life plans have revolved around self-discipline, interjected with unpredictable impulsivity and romance. In 2012 he signed contract with Hanart TZ Gallery but suddenly decided to run for election to challenge Ma Fung-Kwok. "I told Johnson Chang (director of Hanart TZ) only after making the decision. He did not object. I stopped my art work for a year. If I have to choose again, I would do the same." His friends supported him but big bosses told him, "No one would buy your paintings if you do this. That’s true. No one in the business circle will buy the paintings of an artist who opposes the government. Where can they put these paintings on display?”

With age comes increasing personal freedom. Painters mostly work on an individual basis. Chow says he has more freedom now. His sense of independent identity has grown stronger in recent years. He even let go of his identity as a founder of the Fotanian arts community. Does his clear-cut stance affect his career? "Actually I don't know whether it has any impact. Just like once, I know some pro-establishment collectors were upset as they felt betrayed. They probably thought, ‘We have supported these artists for a long time but when the country needs them, how could they treat the country like this?’ I know they are deeply dissatisfied." When he reflected on the purpose of his creation, it was all about having the freedom to do whatever he wanted.

From a city of social movement to a city under lockdown due to the pandemic, Chow has cried while watching live broadcasts. He had nightmares, but he feels emotionally stable now. "I don't normally express emotions a lot. To me, this is already very serious. My artwork tends to be quite detached. I don't normally express my emotions." The situation of Hong Kong in past several months reminded him of his days in Beijing. He had a studio in Beijing. The lease was supposed to last for 6 years yet the place was forcibly demolished in the third year. "I had seen enough by that time. I just packed up." At the time there was a group of Beijing artists who protested for their rights. They rallied on the streets. He heard some people posed as residents and passers-by causing trouble and fighting. It turned out that Public Security officers were the ones beating people up on the streets. "CCP uses the same old tactics - infiltration and inducing people to get on their side. At the end they will settle the troubles with money but not everyone is fairly paid, thereby planting the seeds for internal rivalries. I am not optimistic or pessimistic about the future of Hong Kong.” He plans to continue his art work and stay in Hong Kong. "It’s just that what I experienced in Beijing is now happening in Hong Kong."

Source of text and photos: Hong Kong Economic Journal, March 2020

https://lj.hkej.com/lj2017/artculture/article/id/2416799/%E3%80%90%E9%80%99%E5%80%8BArt+Month%E4%B8%8D%E5%A4%AA%E5%86%B7%E3%80%91%E5%91%A8%E4%BF%8A%E8%BC%9D%EF%BC%9A%E8%A1%80%E8%88%87%E6%B7%9A%E7%9A%84%E8%83%8C%E5%BD%B1+Portraits+from+Behind