Africa Sacrifice

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Reviewed Work: Sacrifice in Africa: A Structuralist Approach by Luc de Heusch, Linda O'Brien, Alice Morton

Published By: The University of Chicago Press

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1062232

Current issues are now on the Chicago Journals website. Read the latest issue.For nearly fifty years, History of Religions has set the standard for the study of religious phenomena from prehistory to modern times. History of Religions strives to publish scholarship that reflects engagement with particular traditions, places, and times and yet also speaks to broader methodological and/or theoretical issues in the study of religion. Toward encouraging critical conversations in the field, HR also publishes review articles and comprehensive book reviews by distinguished authors.

Since its origins in 1890 as one of the three main divisions of the University of Chicago, The University of Chicago Press has embraced as its mission the obligation to disseminate scholarship of the highest standard and to publish serious works that promote education, foster public understanding, and enrich cultural life. Today, the Journals Division publishes more than 70 journals and hardcover serials, in a wide range of academic disciplines, including the social sciences, the humanities, education, the biological and medical sciences, and the physical sciences.

Note: This article is a review of another work, such as a book, film, musical composition, etc. The original work is not included in the purchase of this review.

This item is part of a JSTOR Collection.

For terms and use, please refer to our Terms and Conditions

History of Religions © 1986 The University of Chicago Press

Request Permissions

JSTOR is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization helping the academic community use digital technologies to preserve the scholarly record and to advance research and teaching in sustainable ways.

©2000-2021 ITHAKA. All Rights Reserved. JSTOR®, the JSTOR logo, JPASS®, Artstor®, Reveal Digital™ and ITHAKA® are registered trademarks of ITHAKA.

Export a RIS file (For EndNote, ProCite, Reference Manager, Zotero, Mendeley…)

Note: Always review your references and make any necessary corrections before using. Pay attention to names, capitalization, and dates.

With a personal account, you can read up to 100 articles each month for free.

Monthly Plan

Access everything in the JPASS collection

Read the full-text of every article

Download up to 10 article PDFs to save and keep

$19.50/month

Yearly Plan

Access everything in the JPASS collection

Read the full-text of every article

Download up to 120 article PDFs to save and keep

$199/year

How does it work?

Select the purchase option.

Check out using a credit card or bank account with PayPal.

Read your article online and download the PDF from your email or your account.

Why register for an account?

Access supplemental materials and multimedia.

Unlimited access to purchased articles.

Ability to save and export citations.

Custom alerts when new content is added.

Register/Login Proceed to Cart × Close Overlay

ITHAKA websites use cookies for different purposes, such as to ensure web site function, display non-targeted ads, provide social media features, and track usage. You may manage non-essential cookies in “Cookie Settings”. For more information, please see our Cookie Policy.

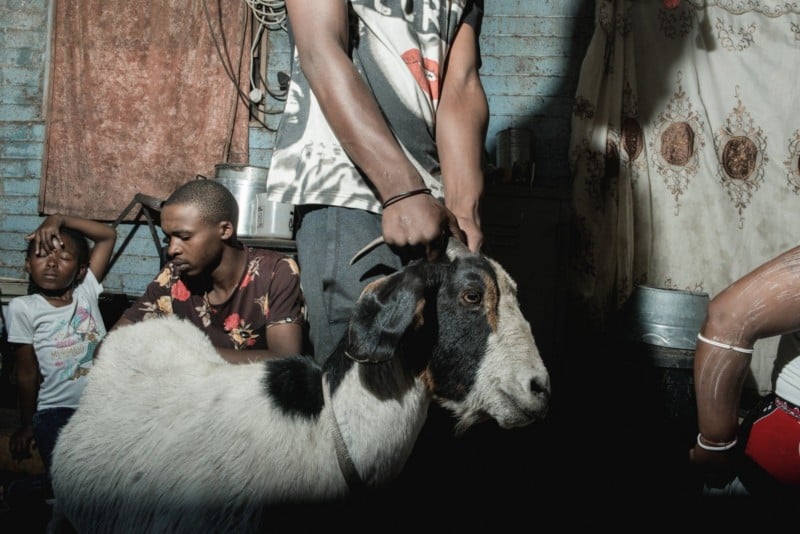

In many African communities, human sacrifice was done for a number of reasons, but mainly it was intended to bring good fortune and to appease the gods. For instance, some African communities offered human sacrifices to celebrate the completion of a new building, such as a temple or a bridge.

face2faceafrica.com/article/african-…

Why is the tradition of human sacrifice in Africa?

Why is the tradition of human sacrifice in Africa?

Human rights defenders have called on African governments and the international community to ensure that all vulnerable people, including albinos, are fully protected and decisive actions are taken against their attackers. There is also the need to educate people about the dangers of human sacrifice and discrimination against people with albinism.

face2faceafrica.com/article/african-human-…

Which is the best definition of human sacrifice?

Which is the best definition of human sacrifice?

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans, usually as an offering to a deity, as part of a ritual.

en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_sacrifice

What was the purpose of the animal sacrifice?

What was the purpose of the animal sacrifice?

Animal sacrifice rituals are made to this day to appease the spirit of the animal that would be sacrificed. He is made to understand that he is not killed for pleasure or for nothing, but out of necessity.

howafrica.com/the-meaning-of-offerings-an…

When did human sacrifice become less common in the Old World?

When did human sacrifice become less common in the Old World?

By the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE), with the associated developments in religion (the Axial Age ), human sacrifice was becoming less common throughout the Old World, and came to be looked down upon as barbaric during classical antiquity.

en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_sacrifice

https://face2faceafrica.com/article/african-human-sacrifice

Перевести · 13.01.2017 · The culture of human sacrifice is said to be rampant in many African countries, including Nigeria, Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Swaziland, South Africa, …

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1062232

human sacrifice, that is, the ritual killing of a sovereign. There is no question that Sacrifice in Africa is a truly important work not only for Africanists but also for students of non-African …

https://howafrica.com/the-meaning-of-offerings-and-sacrifices-in-african-tradition

Перевести · 09.09.2017 · Revealed religions having largely inspired Africa, they have taken up these ideas of human sacrifices and as in Africa, have replaced humans to sacrifice not animal symbols. One can see it when in the Bible Abraham tries to sacrifice his own son and then finally sacrifices an animal instead of his son.

https://biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/ajet/10-1_003.pdf

One purpose of African sacrifice is to offer an animal (or sometimes a human being) to take the place of another individual or a …

Child Sacrifice: Epidemic in Uganda

The Child Sacrifice Business in Uganda

AFRICA BLOOD SACRIFICE/OCCULT WORLD

Uganda Child Sacrifice 2 of 2 - BBC Our World Documentary

Child Sacrifice Is Still Going On In Uganda

Child sacrifice is on the rise in Uganda. Meet the team fighting witch doctors.

https://www.dreamstime.com/photos-images/africa-sacrifice.html

Перевести · Your Africa Sacrifice stock images are ready. Download all free or royalty-free photos and vectors. Use them in commercial designs under …

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_sacrifice

Ancient Near East

Ancient Egypt

There may be evidence of retainer sacrifice in the early dynastic period at Abydos, when on the death of a King he would be accompanied with servants, and possibly high officials, who would continue to serve him in eternal life. The skeletons that were found had no obvious signs of trauma, leading to speculation t…

Ancient Near East

Ancient Egypt

There may be evidence of retainer sacrifice in the early dynastic period at Abydos, when on the death of a King he would be accompanied with servants, and possibly high officials, who would continue to serve him in eternal life. The skeletons that were found had no obvious signs of trauma, leading to speculation that the giving up of life to serve the King may have been a voluntary act, possibly carried out in a drug induced state. At about 2800 BCE, any possible evidence of such practices disappeared, though echoes are perhaps to be seen in the burial of statues of servants in Old Kingdom tombs.

Levant

References in the Bible point to an awareness of and disdain of human sacrifice in the history of ancient near-eastern practice. During a battle with the Israelites, the King of Moab gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering (olah, as used of the Temple sacrifice) (2 Kings 3:27). The Bible then recounts that, following the King's sacrifice, "There was great indignation [or wrath] against Israel" and that the Israelites had to raise their siege of the Moabite capital and go away. This verse had perplexed many later Jewish and Christian commentators, who tried to explain what the impact of the Moabite King's sacrifice was, to make those under siege emboldened while disheartening the Israelites, make God angry at the Israelites or the Israelites fear his anger, make Chemosh (who the Moabites considered to be a god) angry, or otherwise. Whatever the explanation, evidently at the time of writing, such an act of sacrificing the firstborn son and heir, while prohibited by Israelites (Deuteronomy 12:31; 18:9-12), was considered as an emergency measure in the Ancient Near East, to be performed in exceptional cases where divine favor was desperately needed.

The binding of Isaac appears in the Book of Genesis (22); the story appears in the Quran, though Islamic tradition holds that Ismael was the one to be sacrificed. In both the Quranic and Biblical stories, God tests Abraham by asking him to present his son as a sacrifice on Moriah. Abraham agrees to this command without arguing. The story ends with an angel stopping Abraham at the last minute and providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. Many Bible scholars have suggested this story's origin was a remembrance of an era when human sacrifice was abolished in favour of animal sacrifice.

Another probable instance of human sacrifice mentioned in the Bible is the sacrifice of Jephthah's daughter in Judges 11. Jephthah vows to sacrifice to God whatsoever comes to greet him at the door when he returns home if he is victorious. The vow is stated in the Book of Judges, 11:31: "Then it shall be, that whatsoever cometh forth of the doors of my house to meet me, when I return in peace from the children of Ammon, shall surely be the Lord's, and I will offer Him a burnt offering." When he returns from battle, his virgin daughter runs out to greet him. She begs for, and is granted, "two months to roam the hills and weep with my friends", after which "he [Jephthah] did to her as he had vowed."

Two kings of Judah, Ahaz and Manassah, sacrificed their sons. Ahaz, in 2 Kings 16:3, sacrificed his son. "...He even burned his son as an offering, according to the despicable practices of the nations whom the Lord drove out before the people of Israel (ESV)." King Manasseh sacrificed his sons in 2 Chronicles 33:6. "And he burned his sons as an offering in the Valley of the Son of Hinnom... He did much evil in the sight of the Lord, provoking him to anger (ESV)."

Phoenicia

According to Roman and Greek sources, Phoenicians and Carthaginians sacrificed infants to their gods. The bones of numerous infants have been found in Carthaginian archaeological sites in modern times, but the subject of child sacrifice is controversial. In a single child cemetery called the Tophet by archaeologists, an estimated 20,000 urns were deposited.

Plutarch (c. 46–120 CE) mentions the practice, as do Tertullian, Orosius, Diodorus Siculus and Philo. Livy and Polybius do not. The Bible asserts that children were sacrificed at a place called the tophet ("roasting place") to the god Moloch. According to Diodorus Siculus's Bibliotheca historica, "There was in their city a bronze image of Cronus extending its hands, palms up and sloping toward the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire."

Plutarch, however, claims that the children were already dead at the time, having been killed by their parents, whose consent—as well as that of the children—was required; Tertullian explains the acquiescence of the children as a product of their youthful trustfulness.

The accuracy of such stories is disputed by some modern historians and archaeologists.

Europe

Neolithic Europe

There is archaeological evidence of human sacrifice in Neolithic to Eneolithic Europe.

Greco-Roman antiquity

The ancient ritual of expelling certain slaves, cripples, or criminals from a community to ward off disaster (known as Pharmakos), would at times involve publicly executing the chosen prisoner via throwing them off of a cliff.

References to human sacrifice can be found in Greek historical accounts as well as mythology. The human sacrifice in mythology, the deus ex machina salvation in some versions of Iphigeneia (who was about to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon) and her replacement with a deer by the goddess Artemis, may be a vestigial memory of the abandonment and discrediting of the practice of human sacrifice among the Greeks in favour of animal sacrifice.

In ancient Rome, human sacrifice was infrequent but documented. Roman authors often contrast their own behavior with that of people who would commit the heinous act of human sacrifice. These authors make it clear that such practices were from a much more uncivilized time in the past, far removed. It is thought that many ritualistic celebrations and dedications to gods used to involve human sacrifice but have now been replaced with symbolic offerings. Dionysius of Halicarnassus says that the ritual of the Argei, in which straw figures were tossed into the Tiber river, may have been a substitute for an original offering of elderly men. Cicero claims that puppets thrown from the Pons Suplicius by the Vestal Virgins in a processional ceremony were substitutes for the past sacrifice of old men. After the Roman defeat at Cannae, two Gauls and two Greeks in male–female couples were buried under the Forum Boarium, in a stone chamber used for the purpose at least once before. In Livy's description of these sacrifices, he distances the practice from Roman tradition and asserts that the past human sacrifices evident in the same location were “wholly alien to the Roman spirit." The rite was apparently repeated in 113 BCE, preparatory to an invasion of Gaul. They buried both the Greeks and the two Gauls alive as a plea to the gods to save Rome from destruction at the hands of Hannibal. When the Romans conquered the Celts in Gaul, they tortured the people by cutting off their hands and feet and leaving them to die. The Romans justified their actions by also accusing the Celts of practicing human sacrifice.

According to Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice was banned by law during the consulship of Publius Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus in 97 BCE, although by this time it was so rare that the decree was largely symbolic. The Romans also had traditions that centered around ritual murder, but which they did not consider to be sacrifice. Such practices included burying unchaste Vestal Virgins alive and drowning hermaphroditic children. These were seen as reactions to extraordinary circumstances as opposed to being part of Roman tradition. Vestal Virgins who were accused of being unchaste were put to death, and a special chamber was built to bury them alive. This aim was to please the gods and restore balance to Rome. Human sacrifices, in the form of burying individuals alive, were not uncommon during times of panic in ancient Rome. However, the burial of unchaste Vestal Virgins was also practiced in times of peace. Their chasteness was thought to be a safeguard of the city, and even in punishment, the state of their bodies was preserved in order to maintain the peace.

Captured enemy leaders were only occasionally executed at the conclusion of a Roman triumph, and the Romans themselves did not consider these deaths a sacrificial offering. Gladiator combat was thought by the Romans to have originated as fights to the death among war captives at the funerals of Roman generals, and Christian polemicists such as Tertullian considered deaths in the arena to be little more than human sacrifice. Over time, participants became criminals and slaves, and their death was considered a sacrifice to the Manes on behalf of the dead.

Political rumors sometimes centered around sacrifice and in doing so, aimed to liken individuals to barbarians and show that the individual had become uncivilized. Human sacrifice also became a marker and defining characteristic of magic and bad religion.

Celts

According to Roman sources, Celtic Druids engaged extensively in human sacrifice. According to Julius Caesar, the slaves and dependents of Gauls of rank would be burnt along with the body of their master as part of his funerary rites. He also describes how they built wicker figures that were filled with living humans and then burned. According to Cassius Dio, Boudica's forces impaled Roman captives during her rebellion against the Roman occupation, to the accompaniment of revelry and sacrifices in the sacred groves of Andate. Different gods reportedly required different kinds of sacrifices. Victims meant for Esus were hanged or tied to a tree and flogged to death, Tollund Man being an example, those meant for Taranis immolated and those for Teutates drowned. Some, like the Lindow Man, may have gone to their deaths willingly.

Ritualised decapitation was a major religious and cultural practice that has found copious support in the archaeological record, including the numerous skulls discovered in Londinium's River Walbrook and the twelve headless corpses at the French late Iron Age sanctuary of Gournay-sur-Aronde.

Germanic peoples

Human sacrifice was not a particularly common occurrence among the Germanic peoples, being resorted to in exceptional situations arising from crises of an environmental (crop failure, drought, famine) or social (war) nature, often thought to derive at least in part from the failure of the king to establish and/or maintain prosperity and peace (árs ok friðar) in the lands entrusted to him. In later Scandinavian practice, human sacrifice appears to have become more institutionalised and was repeated as part of a larger sacrifice on a periodic basis (according to Adam of Bremen, every nine years).

Evidence of Germanic practices of human sacrifice predating the Viking Age depend on archaeology and on a few scattered accounts in Greco-Roman ethnography. For example, Roman writer Tacitus reported Germanic human sacrifice to what he interpreted as Mercury and Isis, specifically among the Suebians. He also claimed that Germans sacrificed Roman commanders and officers after the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Jordanes reports how the Goths sacrificed prisoners of war to Mars, suspending the severed arms of the victims from the branches of trees.

By the 10th century, Germanic paganism had become restricted to Scandinavia. One account by Ahmad ibn Fadlan as part of his account of an embassy to the Volga Bulgars in 921 claims that Norse warriors were sometimes buried with enslaved women with the belief

Brazzers Hd Milf Com

Very Young Nude Photos

Hard Nipples In Tops

Femdom Clean Up Pussy Creampie

Lesbian Scat Poo Fart Porn

Why the Horrible Tradition of Human Sacrifice in Africa ...

Sacrifice in Africa - JSTOR

SACRIFICE IN AFRICAN TRADmON AND IN BmUCAL PE…

250 Africa Sacrifice Photos - Free & Royalty-Free Stock ...

Human sacrifice - Wikipedia

Africa Sacrifice