3. Wine in Greece and Rome. The Delight of Wine

Tom Standage (2005)Quickly, bring me a beaker of wine, so that I may wet my mind and say something clever.

—Aristophanes, Greek comic poet (c. 450-385 BCE)

A Great Feast

One of the greatest feasts in history was given by King Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria, around 870 BCE, to mark the inauguration of his new capital at Nimrud. At the center of the new city was a large palace, built on a raised mudbrick platform in the traditional Mesopotamian manner. Its seven magnificent halls had ornate wood-and-bronze doors and were roofed with cedar, cypress, and juniper wood. Elaborate murals celebrated the king's military exploits in foreign lands. The palace was surrounded by canals and waterfalls, and by orchards and gardens filled with both local plants and those gathered during the king's far-flung military campaigns: date palms, cedars, cypresses, olive, plum, and fig trees, and grapevines, all of which "vied with each other in fragrance," according to a contemporary cuneiform inscription. Ashur-nasirpal populated his new capital with people from throughout his empire, which covered much of northern Mesopotamia. With these cosmopolitan populations of plants and people, the capital represented the king's empire in microcosm. Once construction was completed, Ashurnasirpal staged an enormous banquet to celebrate.

The feasting went on for ten days. The official record attests that the celebration was attended by 69,574 people: 47,074 men and women from across the empire, 16,000 of the new inhabitants of Nimrud, 5,000 foreign dignitaries from other states, and 1,500 palace officials. The aim was to demonstrate the king's power and wealth, both to his own people and to foreign representatives. The attendees were collectively served 1,000 fattened cattle, 1,000 calves, 10,000 sheep, 15,000 lambs, 1,000 spring lambs, 500 gazelles, 1,000 ducks, 1,000 geese, 20,000 doves, 12,000 other small birds, 10,000 fish, 10,000 jerboa (a kind of small rodent), and 10,000 eggs. There were not many vegetables: a mere 1,000 crates were provided. But even allowing for some kingly exaggeration, it was clearly a feast on an epic scale. The king boasted of his guesrs that "[he] did them due honors and sent them back, healthy and happy, to their own countries."

Yet what was most impressive, and most significant, was the king's choice of drink. Despite his Mesopotamian heritage, Ashurnasirpal did not give pride of place at his feast to the Mesopotamians' usual beverage. Carved stone reliefs at the palace do not show him sipping beer through a straw; instead, he is depicted elegantly balancing a shallow bowl, probably made of gold, on the tips of the fingers of his right hand, so that it is level with his face. This bowl contained wine.

Beer had not been banished: Ashurnasirpal served ten thousand jars of it at his feast. But he also served ten thousand skins of wine—an equal quantity, but a far more impressive display of wealth. Previously, wine had only been available in Mesopotamia in very small quantities, since it had to be imported from the mountainous, wine-growing lands to the northeast. The cost of transporting wine down from the mountains to the plains made it at least ten times more expensive than beer, so it was regarded as an exotic foreign drink in Mesopotamian culture. Accordingly, only the elite could afford to drink it, and its main use was religious; its scarcity and high price made it worthy for consumption by the gods, when it was available. Most people never tasted it at all.

So Ashurnasirpal's ability to make wine and beer available to his seventy thousand guests in equal abundance was a vivid illustration of his wealth. Serving wine from distant regions within his empire also underlined the extent of his power. More impressive still was the fact that some of the wine had come from the vines in his own garden. These vines were intertwined with trees, as was customary at the time, and were irrigated with an elaborate system of canals. Ashurnasirpal was not only fabulously rich, but his wealth literally grew on trees. The dedication of the new city was formally marked with a ritual offering to the gods of this local wine.

Subsequent banquet scenes from Nimrud show people drinking wine from shallow bowls, seated on wooden couches and flanked by attendants, some of whom hold jugs of wine, while others hold fans, or perhaps flyswatters to keep insects away from the precious liquid. Sometimes large storage vessels are also depicted, from which the attendants refill their serving jugs.

Under the Assyrians, wine drinking developed into an increasingly elaborate and formal social ritual. An obelisk from around 825 BCE shows Ashurnasirpal's son, Shalmaneser III, standing beneath a parasol. He holds a wine bowl in his right hand, his left hand rests on the hilt of his sword, and a supplicant kneels at his feet. Thanks to this kind of propaganda, wine and its associated drinking paraphernalia became emblems of power, prosperity, and privilege.

"The Excellent 'Beer' of the Mountains"

Wine was newly fashionable, but it was anything but new. As with beer, its origins are lost in prehistory: its invention, or discovery, was so ancient that it is recorded only indirectly, in myth and legend. But archaeological evidence suggests that wine was first produced during the Neolithic period, between 9000 and 4000 BCE, in the Zagros Mountains in the region that roughly corresponds to modern Armenia and northern Iran. The convergence of three factors made wine production in this area possible: the presence of the wild Eurasian grape vine, Vitis vinifera sylvestris, the availability of cereal crops to provide yearround food reserves for wine-making communities, and, around 6000 BCE, the invention of pottery, instrumental for making, storing, and serving wine.

Wine consists simply of the fermented juice of crushed grapes. Natural yeasts, present on the grape skins, convert the sugars in the juice into alcohol. Attempts to store grapes or grape juice for long periods in pottery vessels would therefore have resulted in wine. The earliest physical evidence for it, in the form of reddish residue inside a pottery jar, comes from Hajji Firuz Tepe, a Neolithic village in the Zagros Mountains. The jar has been dated to 5400 BCE. Wine's probable origin in this region is reflected in the biblical story of Noah, who is said to have planted the first vineyard on the slopes of nearby Mount Ararat after being delivered from the flood.

From this birthplace, knowledge of wine making spread west to Greece and Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), and south through the Levant (modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and Israel) to Egypt. In around 3150 BCE one of Egypt's earliest rulers, King Scorpion I, was buried with seven hundred jars of wine, imported at great expense from the southern Levant, a significant wine-producing area at the time. Once the pharaohs acquired a taste for wine, they established their own vineyards in the Nile Delta, and limited domestic production was under way by 3000 BCE. As in Mesopotamia, however, consumption was restricted to the elite, since the climate was unsuitable for large-scale production. Winemaking scenes appear in tomb paintings, but these give a disproportionate impression of its prevalence in Egyptian society, for only the wine-drinking rich could afford lavish tombs. The masses drank beer.

A similar situation prevailed in the eastern Mediterranean, where vines were being cultivated by 2500 BCE on Crete, and possibly in mainland Greece too. That the vine was introduced, rather than having always been present, was acknowledged in later Greek myths, according to which the gods drank nectar (presumably mead), and wine was introduced later for human consumption. Grapevines were grown alongside olives, wheat, and barley and were often intertwined with olive or fig trees. In the Mycenaean and Minoan cultures of the second millennium BCE, on the Greek mainland and on Crete, respectively, wine remained an elite drink, however. It is not listed in ration tablets for slave workers or lower-ranking religious officials. Access to wine was a mark of status.

The reigns of Ashurnasirpal and his son, Shalmaneser, there fore marked a turning point. Wine came to be seen as a social as well as a religious beverage and started to become increasingly fashionable throughout the Near East and the eastern Mediterranean. And its availability grew in two senses. First, wine production increased, as did the volume of wine being traded by sea, making wine available over a larger geographic area. The establishment of ever-larger states and empires boosted the availability of wine, for the fewer borders there were to cross, the fewer taxes and tolls there were to pay, and the cheaper it was to transport wine over long distances. The luckiest rulers, like the Assyrian kings, had empires that encompassed wine-making regions. Second, as volumes grew and prices fell, wine became accessible to a broader segment of society. The growing availability of wine is evident in the records that list the tribute presented to the Assyrian court. During the reigns of Ashurnasirpal and Shalmaneser, wine began to be mentioned as a desirable tribute offering, along with gold, silver, horses, cattle, and other valuable items. But two centuries later it had vanished from the tribute lists, because it had become so widespread, at least in Assyria, that it was no longer deemed expensive or exotic enough for use as an offering.

Cuneiform tablets from Nimrud dating from around 785 BCE show that by that time wine rations were being provided to as many as six thousand people in the Assyrian royal household. Ten men were allocated one qa of wine per day to share between them; this amount is thought to have been about one liter, so each man would have received roughly one modern glass of wine per day. Skilled workers got more, with one qa being divided between six of them. But everyone in the household, from the highest officials to the lowliest shepherd boys and assistant cooks, was granted a ration.

As the enthusiasm for wine spread south into Mesopotamia, where local production was impractical, the wine trade along the Euphrates and Tigris rivers expanded. Given its heavy and perishable nature, wine was difficult to transport over land. Long-distance trade was done over water, using rafts or boats made of wood and reeds. The Greek historian Herodotus, who visited the region around 430 BCE, described the boats used to carry goods by river to Babylon and noted that "their chief freight is wine." Herodotus explained that once they had arrived downstream and had been unloaded, the boats were nearly worthless, given the difficulty of transporting them back upstream. Instead, they were broken up and sold, though typically only for a tenth of their original value.

This cost was reflected in the high price of the wine.

So though wine became more fashionable in Mesopotamian society, it never became widely affordable outside wine-producing areas. The prohibitive cost for most people is shown by the boast made by Nabonidus, the last ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire before it fell to the Persians in 539 BCE. Nabonidus bragged that wine, which he referred to as "the excellent 'beer' of the mountains, of which my country has none," had become so abundant during his reign that an imported jar containing eighteen sila (about eighteen liters, or twenty-four modern wine bottles) could be had for one shekel of silver. At the time, one shekel of silver per month was regarded as the minimum wage, so wine could only have become an everyday drink among the very rich. For everyone else, a substitute drink became popular instead: date-palm wine, an alcoholic drink made from fermented date syrup. Date palms were widely cultivated in southern Mesopotamia, so the resulting "wine" was just a little more expensive than beer. During the first millennium BCE, even the beer-loving Mesopotamians turned their backs on beer, which was dethroned as the most cultured and civilized of drinks, and the age of wine began.

The Cradle of Western Thought

The origins of contemporary Western thought can be traced back to the golden age of ancient Greece in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, when Greek thinkers laid the foundations for modern Western politics, philosophy, science, and law. Their novel approach was to pursue rational inquiry through adversarial discussion: The best way to evaluate one set of ideas, they decided, was by testing it against another set of ideas. In the political sphere, the result was democracy, in which supporters of rival policies vied for rhetorical supremacy; in philosophy, it led to reasoned arguments and dialogues about the nature of the world; in science, it prompted the construction of competing theories to try to explain natural phenomena; in the field of law, the result was the adversarial legal system. (Another form of institutionalized competition that the Greeks particularly loved was athletics.) This approach underpins the modern Western way of life, in which politics, commerce, science, and law are all rooted in orderly competition.

The idea of the distinction between Western and Eastern worlds is also Greek in origin. Ancient Greece was not a unifled nation but a loose collection of citystates, settlements, and colonies whose allegiances and rivalries shifted constantly. But as early as the eighth century BCE, a distinction was being made between the Greek-speaking peoples and foreigners, who were known as barbaroi because their language sounded like incomprehensible babbling to Greek ears. Chief among these barbarians were the Persians to the east, whose vast empire encompassed Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, and Asia Minor (modern Turkey). At first the leading Greek city-states, Athens and Sparta, united to fend off the Persians, but Persia later backed both Sparta and Athens in turn as they fought each other. Eventually, Alexander the Great united the Greeks and defeated Persia in the fourth century BCE. The Greeks defined themselves in opposition to the Persians, believing themselves to be fundamentally different from (and indeed superior to) Asian peoples.

Enthusiasm for civilized competition and Greece's presumed superiority over foreigners were apparent in the Greek love of wine. It was drunk at formal drinking parties, or symposia, which were venues for playful but adversarial discussion in which drinkers would try to outdo each other in wit, poetry, or rhetoric. The formal, intellectual atmosphere of the symposion also reminded the Greeks how civilized they were, in contrast to the barbarians, who either drank lowly, unsophisticated beer or—even worse—drank wine but failed to do so in a manner that met with Greek approval.

In the words of Thucydides, a Greek writer of the fifth century BCE who was one of the ancient world's greatest historians, "the peoples of the Mediterranean began to emerge from barbarism when they learnt to cultivate the olive and the vine." According to one legend, Dionysus, the god of wine, fled to Greece to escape beer-loving Mesopotamia. A more kindly but still rather patronizing Greek tradition relates that Dionysus created beer for the benefit of people in countries where the vine could not be cultivated. In Greece, however, Dionysus had made wine available to everyone, not just the elite. As the playwright Euripides put it in The Bacchae: "To rich and poor alike hath he granted the delight of wine, that makes all pain to cease."

Wine was plentiful enough to be widely affordable because the climate and terrain of the Greek islands and mainland were ideal for viticulture. Cultivation of the vine rapidly took hold throughout Greece from the seventh century BCE, starting in Arcadia and Sparta in the Peloponnese Peninsula, and then spreading up toward Attica, the region around Athens. The Greeks were the first to produce wine on a large commercial scale and took a methodical, even scientific approach to viticulture. Greek writing on the subject begins with Hesiod's Works and Days, written in the eighth century BCE, which incorporates advice on how and when to prune, harvest, and press grapes. Greek vintners devised improvements to the wine press and adopted the practice of growing vines in neat rows, on trellises and stakes, rather than up trees. This allowed more vines to be packed into a given space, increasing yields and providing easier access for harvesting.

Gradually, grain farming was overtaken by the cultivation of grapevines and olives, and wine production switched from subsistence to industrial farming. Rather than being consumed by the farmer and his dependents, wine was produced specifically as a commercial product. And no wonder; a farmer could earn up to twenty times as much from cultivating vines on his land as he could from growing grain. Wine became one of Greece's main exports and was traded by sea for other commodities. In Attica, the switch from grain production to viticulture was so dramatic that grain had to be imported in order to maintain an adequate supply. Wine was wealth; by the sixth century BCE, the propertyowning classes in Athens were categorized according to their vineyard holdings: The lowest class had less than seven acres, and the next three classes up owned around ten, fifteen, and twenty-five acres, respectively.

Wine production was also established on remote Greek islands, including Chios, Thasos, and Lesbos, off the west coast of modern Turkey, whose distinctive wines became highly esteemed. Wine's economic importance was underlined by the appearance of wine-related imagery on Greek coins: Those from Chios portrayed the distinctive profile of its wine jars, and the wine god Dionysus reclining on a donkey was a common motif on both the coins and amphora handles of the Thracian city of Mende. The commercial significance of the wine trade also meant that vineyards became prime targets in the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta and were often trampled and burned. On one occasion, in 424 BCE, Spartan troops arrived just before harvest time at Acanthus, a wine-producing city in Macedonia that was allied with Athens. Fearing for their grapes, and swayed by the oratory of Brasidas, the Spartan leader, the locals held a ballot and decided to switch allegiances.

The harvest was then able to continue unaffected.

As wine became more widely available—so widely available that even the slaves drank it—what mattered was no longer whether or not you drank wine, but what kind it was. For while the availability of wine was more democratic in Greek society than in other cultures, wine could still be used to delineate social distinctions. Greek wine buffs were soon making subtle distinctions between the various homegrown and foreign wines. As individual styles became well known, different wine-producing regions began shipping their wines in distinctively shaped amphorae, so that customers who preferred a particular style could be sure they were getting the real thing. Archestratus, a Greek gourmet who lived in Sicily in the fourth century BCE and is remembered as the author of Gastronomia, one of the world's first cookbooks, preferred wine from Lesbos. References in Greek comic plays of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE suggest that the wines of Chios and Thasos were also particularly highly regarded.

After a wine's place of origin, the Greeks were primarily interested in its age, rather than its exact vintage. They made little distinction between one vintage and the next, probably because variations caused by storage and handling far outweighed the differences between vintages. Old wine was a badge of status, and the older it was, the better. Homer's Odyssey, written in the eighth century BCE, describes the strong room of the mythical hero Odysseus, "where piled-up gold and bronze was lying and clothing in chests and plenty of good-smelling oil: and in it stood jars of old sweet-tasting wine, with the unmixed divine drink in them, packed in rows against the wall."

For the Greeks, wine drinking was synonymous with civilization and refinement: What kind of wine you drank, and its age, indicated how cultured you were. Wine was preferred over beer, fine wines were preferred over ordinary ones, and older wines over young. What mattered even more than your choice of wine, however, was how you behaved when you drank it, which was even more revealing of your innermost nature. As Aeschylus, a Greek poet, put it in the sixth century BCE: "Bronze is the mirror of the outward form; wine is the mirror of the mind."

How to Drink Like a Greek

What most distinguished the Greek approach to wine from that of other cultures was the Greek practice of mixing wine with water before consumption. The pinnacle of social sophistication was the consumption of the resulting mixture at a private drinking party, or symposion. This was an all-male aristocratic ritual that took place in a special "men's room," or andron. Its walls were often decorated with drinking-related murals or paraphernalia, and the use of a special room emphasized the separation between everyday life and the symposion, during which different rules applied. The andron was sometimes the only room in the house with a stone floor, which sloped toward the center to make cleaning easier. Its importance was such that houses were often designed around it.

The men sat on special couches, with a cushion under one arm, a fashion imported from the Near East in the eighth century BCE. Typically, a dozen individuals attended a symposion, and certainly no more than thirty. Although women were not allowed to sit with the men, female servers, dancers, and musicians were often present. Food was served first, with little or nothing to drink. Then the tables were cleared away, and the wine was brought out. The Athenian tradition was to pour three libations: one to the gods, one to fallen heroes, particularly one's ancestors, and one to Zeus, the king of the gods. A young woman might play the flute during this ceremony, and a hymn would then be sung. Garlands of flowers or vine leaves were handed out, and in some cases perfume was applied. Then the drinking could begin.

The wine was first mixed with water in a large, urn-shaped bowl called a krater. Water from a three-handled vessel, the hydria, was always added to wine, rather than the other way around. The amount of water added determined how quickly everyone would become intoxicated. Typical mixing ratios of water to wine seem to have been 2:1, 5:2, 3:1, and 4:1. A mixture of equal parts of water and wine was regarded as "strong wine"; some concentrated wines, which were boiled down before shipping to a half or a third of their original volume, had to be mixed with eight or even twenty times as much water. In hot weather, the wine was cooled by lowering it into a well or mixing it with snow, at least by those who could afford such extravagances. The snow was collected during the winter and kept in underground pits, packed with straw, to keep it from melting.

Drinking even a fine wine without first mixing it with water was considered barbaric by the Greeks, and by the Athenians in particular. Only Dionysus, they believed, could drink unmixed wine without risk. He is often depicted drinking from a special type of vase, the use of which indicates that no water has been added. Mere mortals, in contrast, could only drink wine whose strength had been tempered with water; otherwise they would become extremely violent or even go mad. This was said by Herodotus to have happened to King Cleomenes of Sparta, who picked up the barbaric habit of drinking unmixed wine from the Scythians, a nomadic people from the region north of the Black Sea. Both they and their neighbors the Thra-cians were singled out by the Athenian philosopher Plato as being clueless and uncultured in their use of wine: "The Scythians and Thracians, both men and women, drink unmixed wine, which they pour on their garments, and this they think a happy and glorious institution." Macedonians were also notorious for their fondness for unmixed wine. Alexander the Great and his father, Philip II, were both reputed to have been heavy drinkers.

Alexander killed his friend Clitus in a drunken brawl, and there is some evidence that heavy wine drinking contributed to his death from a mysterious illness in 323 BCE. But it is difficult to evaluate the trustworthiness of such claims, since the equation of virtue with moderate drinking, and corruption with overindulgence, is so widespread in the ancient sources.

Water made wine safe; but wine also made water safe. As well as being free of pathogens, wine contains natural antibacterial agents that are liberated during the fermentation process. The Greeks were unaware of this, though they were familiar with the dangers of drinking contaminated water; they preferred water from springs and deep wells, or rainwater collected in cisterns. The observation that wounds treated with wine were less likely to become infected than those treated with water (again, because of the lack of pathogens and the presence of antibacterial agents) may also have suggested that wine had the power to clean and purify.

Not drinking wine at all was considered just as bad as drinking it neat. The Greek practice of mixing wine and water was thus a middle ground between barbarians who overindulged and those who did not drink at all. Plutarch, a Greek writer from the later Roman period, put it this way: "The drunkard is insolent and rude. . . . On the other hand, the complete teetotaler is disagreeable and more fit for tending children than for presiding over a drinking party."

Neither, the Greeks believed, was able to make proper use of the gift of Dionysus. The Greek ideal was to be somewhere between the two. Ensuring that this was the case was the job of the sym-posiarch, or king of the symposion— either the host, or one of the drinking group, chosen by ballot or a roll of dice. Moderation was the key: The symposiarch's aim was to keep the assembled company on the borderline between sobriety and drunkenness, so that they could enjoy the freedom of tongue and release from worry, but without becoming violent like barbarians.

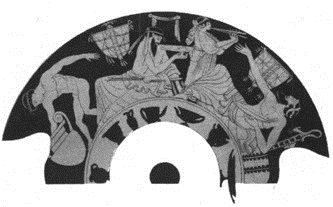

Wine was most frequently drunk from a shallow, two-handled bowl with a short stem called a cylix. It was also sometimes served in a larger, deeper vessel called a cantharos, or a drinking horn called a rhyton. A wine jug, or oinochoe, which in some cases resembled a long-handled ladle, was used by servants, under the direction of the symposiarch, to transfer wine from the krater to the drinking vessels. Once one krater had been emptied, another would be prepared.

Drinking vessels were elaborately decorated, often with Dionysian imagery, and they became increasingly ornate. For pottery vessels, the classic form was the "black-figure" technique, in which figures and objects were represented by areas of black paint, with details picked out by incising lines before firing. This technique, pioneered in Corinth in the seventh century BCE, quickly spread to Athens. From the sixth century BCE, it was progressively replaced by the "redfigure" technique, in which figures were depicted by leaving the natural red color of the clay unpainted, and adding details in black. The survival to this day of so much black-figure and red-figure pottery, including drinking vessels, is misleading, however. The rich drank from silver or gold drinking vessels, rather than pottery. But it is the pottery vessels that survive because they were used in burials.

Adherence to the rules and rituals of wine drinking, and the ' use of the appropriate equipment, furniture, and dress all served to emphasize the drinkers' sophistication. But what actually went on while the wine was being consumed? There is no single answer; the symposion was as varied as life itself, a mirror of Greek society. Sometimes there would be formal entertainment, in the form of hired musicians and dancers. At some symposia, the guests themselves would compete to improvise witty songs, poetry, and repartee; sometimes the symposion was a formal occasion for the discussion of philosophy or literature, to which young men were admitted for educational purposes.

But not all symposia were so serious. Particularly popular was a drinking game called kottabos. This involved flicking the last remaining drops of wine from one's cup at a specific target, such as another person, a disk-shaped bronze target, or even a cup floating in a bowl of water, with the aim of sinking it. Such was the craze for kottabos that some enthusiasts even built special circular rooms in which to play it. Traditionalists expressed concern that young men were concentrating on improving their kottabos rather than javelin throwing, a sport that at least had some practical use in hunting and war.

As one krater succeeded another, some symposia descended into orgies, and others into violence, as drinkers issued challenges to each other to demonstrate loyalty to their drinking group, or hetaireia. The symposion was sometimes followed by the komos, a form of ritual exhibitionism in which the members of the hetaireia would course through the streets in nocturnal revelry to emphasize the strength and unity of their group. The komos could be goodnatured but could also lead to violence or vandalism, depending on the state of the participants. As a fragment from a play by Euboulos puts it: "For sensible men I prepare only three kraters: one for health, which they drink first, the second for love and pleasure, and the third for sleep. After the third one is drained, wise men go home. The fourth krater is not mine anymore—it belongs to bad behavior; the fifth is for shouting; the sixth is for rudeness and insults; the seventh is for fights; the eighth is for breaking the furniture; the ninth is for depression; the tenth is for madness and unconsciousness."

At heart, the symposion was dedicated to the pursuit of pleasure, whether of the intellectual, social, or sexual variety. It was also an outlet, a way of dealing with unruly passions of all kinds. It encapsulated the best and worst elements of the culture that spawned it. The mixture of water and wine consumed in the symposion provided fertile metaphorical ground for Greek philosophers, who likened it to the mixture of the good and bad in human nature, both within an individual and in society at large. The symposion, with its rules for preventing a dangerous mixture from getting out of hand, thus became a lens through which Plato and other philosophers viewed Greek society.

The Philosophy of Drinking

Philosophy is the pursuit of wisdom; and where better to discover the truth than at a symposion, where wine does away with inhibitions to expose truths, both pleasant and unpleasant? "Wine reveals what is hidden," declared Eratosthenes, a Greek philosopher who lived in the third century BCE. That the symposion was thought to be a suitable venue for getting at the truth is emphasized by its repeated use as a literary form, in which several characters debate a particular topic while drinking wine. The most famous example is Plato's Symposium, in which the participants, including Plato's depiction of his men tor, Socrates, discuss the subject of love. After an entire night's drinking, everyone has fallen asleep except Socrates, who remains apparently unaffected by the wine he has drunk and sets off on his day's business. Plato depicts him as the ideal drinker: He uses wine in the pursuit of truth but remains in total control of himself and suffers no ill effects. Socrates also appears in a similar work written by another of his pupils. Xenophon's Symposium, written around 360 BCE, is another fictional account of an Athenian drinking party where the conversation is rather more sparkling and witty, and the characters rather more human, than in Plato's more serious work. The main subject, once again, is love, and the conversation is fueled by fine Thasian wine.

Such philosophical symposia took place more in literary imagination than in real life. But in one respect, at least, wine could be used in everyday life to reveal truth: It could expose the true nature of those drinking it. While he objected to the hedonistic reality of actual symposia, Plato saw no reason why the practice could not, in theory, be put to good use as a test of personality. Speaking through one of the characters in his book Laws, Plato argues that drinking with someone at a symposion is in fact the simplest, fastest, and most reliable test of someone's character. He portrays Socrates postulating a "fear potion" that induces fear in those who drink it. This imaginary drink can then be used to instill fearlessness and courage, as drinkers gradually increase the dose and learn to conquer their fear. No such potion exists, of course; but Plato (speaking, as Socrates, to a Cretan interlocutor) draws an analogy with wine, which he suggests is ideally suited to instill self-control.

What is better adapted than the festive use of wine, in the first place to test, and in the second place to train the character of a man, if care be taken in the use of it? What is there cheaper, or more innocent? For do but consider which is the greater risk: Would you rather test a man of a morose and savage nature, which is the source of ten thousand acts of injustice, by making bargains with him at a risk to yourself, or by having him as a companion at the festival of Dionysus? Or would you, if you wanted to apply a touchstone to a man who is prone to love, entrust your wife, or your sons, or daughters to him, imperiling your dearest interests in order to have a view of the condition of his soul? . . . I do not believe that either a Cretan, or any other man, will doubt that such a test is a fair test, and safer, cheaper, and speedier than any other.Similarly, Plato saw drinking as a way to test oneself, by submitting to the passions aroused by drinking: anger, love, pride, ignorance, greed, and cowardice. He even laid down rules for the proper running of a symposion, which should ideally enable men to develop resistance to their irrational urges and triumph over their inner demons. Wine, he declared, "was given [to man] as a balm, and in order to implant modesty in the soul, and health and strength in the body."

The symposion also lent itself to political analogies. To modern eyes, a gathering at which everyone drank as equals from a shared bowl appears to embody the idea of democracy. The symposion was indeed democratic, though not in the modern sense of the word. It was strictly for privileged men; but the same was true, in the Athenian form of democracy, of the right to vote, which was only extended to free men, or around a fifth of the population. Greek democracy relied on slavery. Without slaves to do all the hard work, the men would not have had enough leisure time to participate in politics.

Plato was suspicious of democracy. For one thing, it interfered with the natural order of things. Why should a man obey his father, or a scholar his teacher, if they were technically equals? Placing too much power in the hands of the ordinary people, Plato argued in his book The Republic, led inevitably to anarchy—at which point order could only be restored through tyranny. In The Republic, he depicted Socrates denouncing proponents of democracy as evil wine pourers who encouraged the thirsty people to overindulge in the "strong wine of freedom." Power, in other words, is like wine and can intoxicate when consumed in large quantities by people who are not used to it. The result in both cases is chaos. This is one of many allusions in The Republic to the symposion, nearly all of which are disparaging. (Plato believed, instead, that the ideal society would be run by an elite group of guardians, led by philosopher kings.)

In short, the symposion reflected human nature and had both good and bad aspects. But provided the right rules were followed, Plato concluded, the good in the symposion could outweigh the bad. Indeed, when he set up his academy, just outside Athens, where he taught philosophy for over forty years and did most of his writing, the symposion provided the model for his style of teaching.

After each day of lectures and debates, he and his students ate and drank together, one chronicler noted, in order to "enjoy each other's company and chiefly to refresh themselves with learned discussion." Wine was served according to Plato's directions, in moderate quantities to ensure that the chief form of refreshment was intellectual; a contemporary observed that those who dined with Plato felt perfectly well the next day. There were no musicians or dancers, for Plato believed that educated men ought to be capable of entertaining themselves by "speaking and listening in turns in an orderly manner." Today, the same format survives as a framework for academic interchange, in the form of the scholarly seminar, or symposium, where participants speak in turn and discussion and argument, within proscribed limits, are encouraged.

An Amphora of Culture

With its carefully calibrated social divisions, its reputation for unparalleled cultural sophistication, and its encouragement of both hedonism and philosophical inquiry, wine embodied Greek culture. These values went along with Greek wine as it was exported far and wide. The distribution of Greek wine jars, or amphorae, provides archaeological evidence for Greek wine's widespread popularity and the far-reaching influence of Greek customs and values. By the fifth century BCE, Greek wine was being exported as far afield as southern France to the west, Egypt to the south, the Crimean Peninsula to the east, and the Danube region to the north. It was trade on a massive scale; a single wreck found off the southern coast of France contained an astonishing 10,000 amphorae, equivalent to 250,000 liters or 333,000 modern wine bottles. As well as spreading wine itself, Greek traders and colonists spread knowledge of its cultivation, introducing wine making to Sicily, southern Italy, and southern France, though whether viticulture was introduced to Spain and Portugal by the Greeks or the Phoenicians (a seafaring culture based in a region of modern-day Syria and Lebanon) is unclear.

A Celtic grave-mound found in central France, dating from the sixth century BCE, contained the body of a young noblewoman lying on the frame of a wagon, the wheels of which had been removed and laid alongside. Among the valuables found in the tomb was a complete set of imported Greek drinking vessels, including an enormous and elaborately decorated krater. Similar vessels have been found in other Celtic graves. Vast amounts of Greek wine and drinking vessels were also exported to Italy, where the Etruscans enthusiastically embraced the custom of the symposion to demonstrate their own sophistication.

Greek customs such as wine drinking were regarded as worthy of imitation by other cultures. So the ships that carried Greek wine were carrying Greek civilization, distributing it around the Mediterranean and beyond, one amphora at a time. Wine displaced beer to become the most civilized and sophisticated of drinks—a status it has maintained ever since, thanks to its association with the intellectual achievements of Ancient Greece.