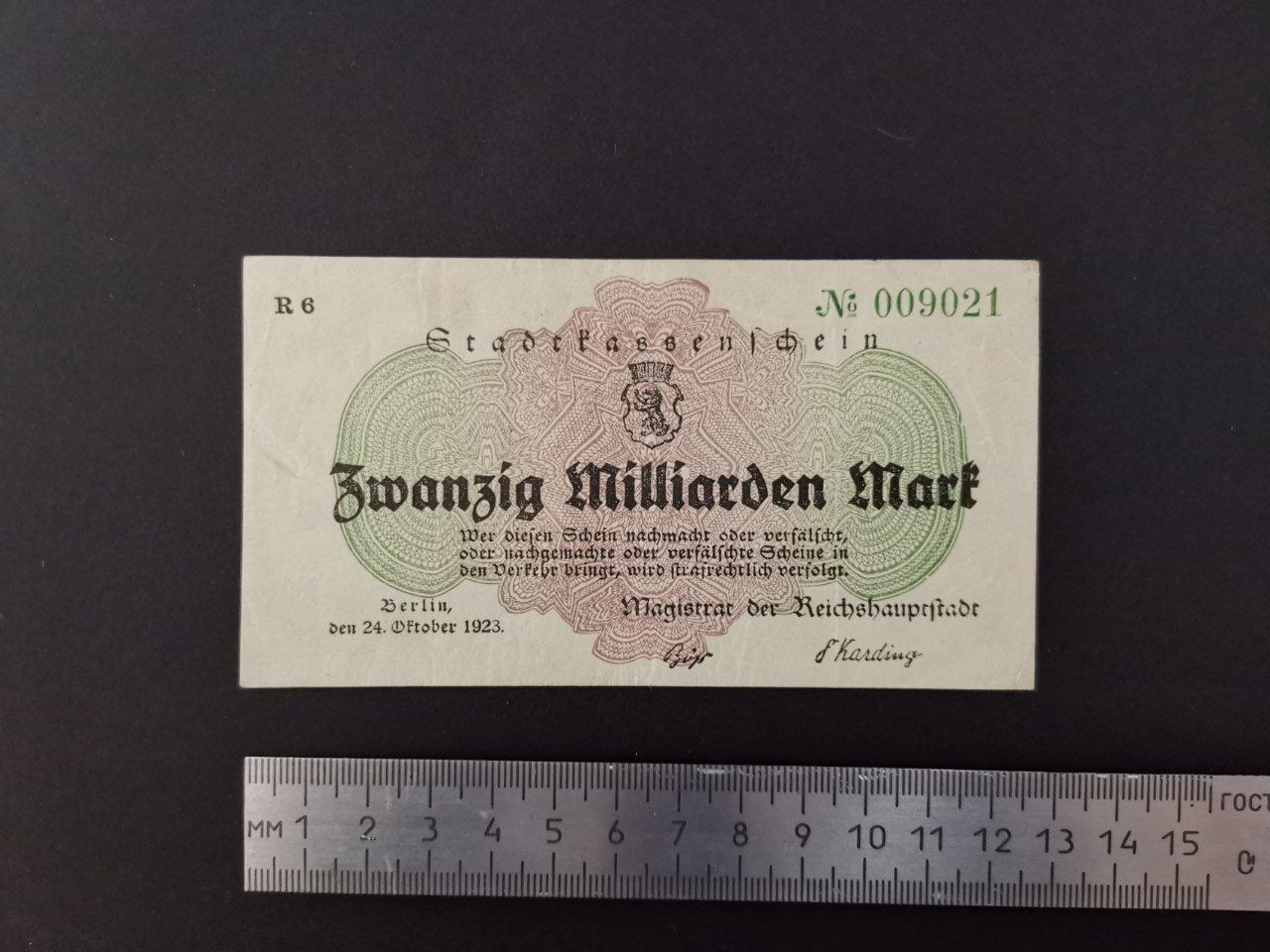

20B Reichsmarks Berlin Emergency Money

Weimar Artifacts

Notgeld literally means "Emergency Money". There is a piece in the book "When Money Dies" by Adam Fergusson which explains the reason for Notgeld or Geldscheine existence:

Because the Reichsbank's printing presses and note-distribution arrangements were insufficient for the situation, a law was passed permitting, under licence and against the deposit of appropriate assets, the issue of emergency money tokens, or Notgeld, by state and local authorities and by industrial concerns when and where the Reichsbank could not satisfy employers' needs for wage-payment. The law's purpose was principally to regularise and regulate a practice which had gone on extensively for some years already, with the difference that authorised Notgeld would now have the Reichsbank's guarantee behind it. Before long, as that guarantee became increasingly less esteemed, the tide of emergency money that now entered local circulation, with or without the Bank's approval, contrived enormously to raise the level of the sea of paper by which the country was engulfed. As the ability to print money privately in a time of accelerating inflation made possible private profits only limited by people's willingness to accept it, the process merely banked up the inflationary fire to ensure a still bigger blaze later on.

Notgeld gave German Weimar Republic hyperinflation such a distinctive feature because they were very different. Here we discuss City of Berlin Notgeld.

This bill was issued at later stages of hyperinflation just by judging from its high denomination of 20 billions of marks. The design is minimalistic and perfectly balanced, it likely allowed cheap production of mass quantities of such bills. The bill leaves and impression of similarity to Bauhaus bills which avoided using classical themes or being ultra maximum utilitarian in a sense of total absence of any graphical details. Quite unexpected to see high rarity Numista rating of 94.

Guttman calls Berlin the great Whore of Babylon:

...when seen through modern eyes, evokes in some respects nothing worse than the image of a “swinging city”. To be sure, the collapse of money led to a revaluation of all values, but this also brought forth a certain creative criticism, however cynical, and a groping for new ideas and forms of expression.

...

The logical need to spend money quickly and the hectic life of insecurity and fear to which people were condemned combined in creating tensions. The result was to seek an outlet for, so to speak, both the money and the tensions. ‘People shook with hysteria when the new dollar rate was published, and the first row with a girl friend made them blow their brains out”, wrote Carl Zuckmayer in his memoirs, describing the Berlin scene. Gambling was widespread and many gambling dens attracted customers in search of excitement and eager to get rid of their money. Prostitutes of both sexes were in demand and they flourished; not stark poverty alone, but also the temptation to make easy money (all the better when it was a dollar note) was an effective recruiting ‘agent for the oldest profession.

Berlin was partying hard and on the other hand "new riches" tried all their best for converting paper moneys into real goods. Carl Firstenberg commented, “The reconstruction of the war-ravaged north of France took place in Dahlem” — one of Berlin’s fashionable and expanding suburbs. Guttman tells a stories about students who made their fortunes while buying property at the peak of inflation.

In such environment various arts flourished and Weimar became a Motherland of German Expressionism and Bauhaus as well, and eventually many movie makers found themselves working in Holywood in 1930s.