National Unity Day: A historical retrospect circa 1612

Russian MFA

National Unity Day was added to Russia’s calendar on November 4, 2005, to celebrate the people’s militia who liberated Moscow from Polish occupation in 1612. The invaders were driven out of the Russian capital, which put an end to the lengthy period of the Time of Troubles and led to the election of a new tsar, Mikhail Romanov.

Today we will tell you about those tragic events and the heroism of the Russian people who did their utmost to save their homeland.

We will begin with Ivan IV or Ivan the Terrible, who had five sons, two of whom – Dmitry and Vasily – died in infancy. His son Ivan died during a quarrel with the tsar, although some historians claim that he died of an illness; Tsarevich Dmitry died in Uglich in 1591 under circumstances that remain a mystery to this day. The group of noblemen led by Boyar Vasily Shuisky, who investigated his death, concluded that it was an accidental death. However, the people suspected that it was a political assassination. Ivan’s surviving son, Feodor, reigned from 1584 to 1598. He died childless, which subsequently led to the coming events.

The death of Feodor I ended the rule of the Rurik dynasty in Russia, and the Zemsky Sobor (National Assembly) elected Boris Godunov as Tsar. The Godunovs were boyars from Kostroma who had served Moscow princes for several centuries but were not considered part of the upper nobility of Muscovy. Boris Godunov rose to prominence thanks to his friendship with Malyuta Skuratov, the leader of the Oprichnina (tsar’s bodyguard corps) whose daughter Boris married in 1570. Godunov’s daughter Irina married Feodor, the son of Ivan the Terrible, which earned her father the boyar title and paved the way to his accession to the throne.

Boris Godunov celebrated his accession with public festivities, announced a general pardon and granted benefits to local nobility. Executions were not held for some time in Russia. Godunov invited foreigners to Russia and gave them tax exemptions, which promoted Russia’s rapprochement with Western countries. But not everyone liked the new tsar or his policy. The famine, which began in 1601 due to several record cold winters and crop disruption, contributed to social discontent and eventually led to the downfall of Boris Godunov.

A rumour spread through the country that Tsarevich Dmitry had miraculously survived the assassination attempt, which meant that Boris Godunov was not elected legitimately. According to the most popular version, False Dmitry, who claimed to be the son of Ivan the Terrible, was a runaway monk called Grigory Otrepyev from the impoverished noble family of the Nelidovs. False Dmitry, as he became known in the country, allegedly told West Russian (Lithuanian-Russian) Prince Adam Wisniowiecki that he was a tsar’s son and established close ties with Polish nobleman Jerzy Mniszech and papal nuncio (diplomat) Claudio Rangoni. In early 1604, False Dmitry met with Sigismund III Vasa, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. Dmitry converted to Catholicism and secured Poland’s support in return for a promise to cede Smolensk and Severia, a historical region in present-day southwest Russia, northern Ukraine and eastern Belarus, to Poland. His army crossed the Russian border in 1604. Boris Godunov died a mysterious death at the height of the military campaign. His 16-year-old son Feodor was declared tsar, but soon afterwards Dmitry’s loyalists killed him and his mother.

False Dmitry made his triumphal entry into Moscow in 1605, where the boyars led by Bogdan Belsky pledged allegiance to him as the legitimate heir to the throne. The “new tsar” declared himself emperor, but not all Moscow boyars believed his claims to legitimacy. Very soon after False Dmitry entered Moscow, Prince Vasily Shuisky spread the rumour that he was a false tsar. The conspiracy was uncovered, Shuisky was arrested and sentenced to death, but the new “tsar” pardoned him as a goodwill gesture.

By May 1606, the discontent with the breach of traditions, suppression of the Orthodox Church, and Poles’ impunity grew to such a proportion that the boyar opposition composed of Vasily Shuisky’s supporters managed to exploit the situation, stirring up a rebellion, during which the impostor was deposed and killed. False Dmitry’s body was burned and the ashes were mixed with gunpowder and fired from a cannon towards the country, Rzeczpospolita, which “he came from.”

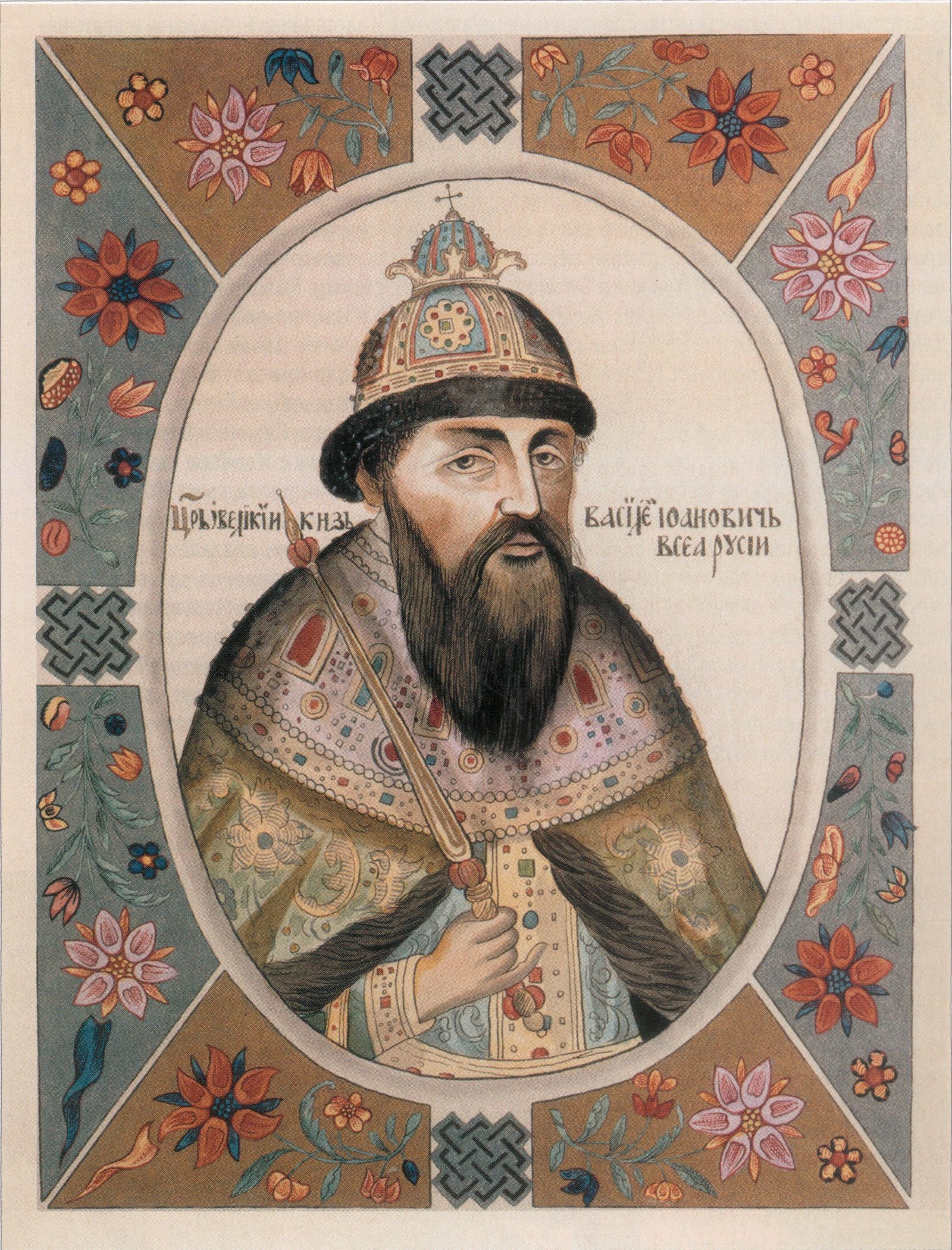

A representative of the Suzdal branch of the Rurik dynasty, Boyar Vasily Shuisky, came to power to start his reign with a bold initiative: he declared that Boris Godunov was behind the murder of Tsarevich Dmitry. But a change of regime failed to bring the desired transformations and peace. Between 1606 and 1607, the south was a scene of Ivan Bolotnikov’s uprising, which gave rise to the “thieves” movement.

In the summer of 1607, a new impostor, who came down in history as False Dmitry II, turned up in Starodub. He was of an obscure origin and known as Tushino Thief, a nickname given to him by his political opponents. A considerable share of Russian towns voluntarily took his side and many others were subdued by force. It was only the Trinity Lavra of St Sergius that withstood a protracted siege, which lasted from September 1608 to January 1610. In this situation, Shuisky asked Sweden for help in exchange for territorial concessions. Rzeczpospolita was quick to take advantage of this under the pretext that Moscow had signed a treaty with a state hostile to them. In September 1609, it declared a war on Russia and King Sigismund III marched towards Smolensk. In February 1610, a Russian-Swedish army liberated Moscow, with Tushino Thief fleeing to Kaluga.

On July 4, 1610, the Battle of Klushino was fought, in which the Polish army defeated the Russian-Swedish army because Russia-hired German mercenaries unexpectedly defected to the enemy’s side. This opened to Poles the direct road to Moscow. Informed about this, False Dmitry II launched an offensive from the south, capturing Serpukhov, Borovsk, and the Borovsk Monastery of St Paphnutius. Shuisky army’s defeat in the Battle of Klushino and the comeback of False Dmitry II was the last straw that ruined the tsar’s reputation in the eyes of the Russian nobility. Another coup took place in Moscow and the power was seized by a council of seven boyars, or Semiboyarshchina, which recognised Wladyslaw, son of Sigismund III, as the Russian tsar.

The pillage and violence perpetrated across Russian cities by the Polish and Lithuanian troops, the northern towns pillaged by Swedes, the former allies, as well as inter-faith strife, topped with False Dmitry II’s death in December 1610, all this combined to give a new impetus to the national liberation movement, picked up and continued by the first and second militias.

Prokopy Lyapunov, a nobleman from Ryazan, headed the first militia in 1611. Some of False Dmitry II supporters, as well as the Cossacks under Ivan Zarutsky’s command joined him. Still the first militia failed to chase the invaders from Moscow. The fact that its members had opposing visions of the country’s future system of government doomed the first militia. Some wanted to maintain the freedoms intact, while others demanded stronger top-down rule. In addition, Zarutsky and Lyapunov competed for leadership against one another, and the Poles quickly jumped on this occasion by sending fake letters to the Cossacks alleging that Lyapunov wanted to annihilate the Cossacks. They responded by inviting Lyapunov to a Cossack assembly in July 1611 and killed him when a dispute erupted. After that, most noblemen withdrew from the militia.

The second militia emerged in September 1611. It all started in the Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Saviour in Nizhny Novgorod’s Kremlin after a church service, when Archpriest Savva presented a summon in which he called on the parishioners to stand up for saving their faith. After that, Kuzma Minin, a community leader, addressed the crowd with the following words:

This was how he called on the people to collect funds for a new militia. To prevent it from following down the same path at the first militia, it was staffed by servicemen. People supported Minin’s proposal in one voice and appointed him to manage the fundraising effort and oversee the distribution of money among the members of the nascent militia.

Prince Dmitry Pozharsky headed the militia. Coming from the Rurik dynasty, he has been fighting the invaders throughout the invasion. When the second militia was created, he was staying at his family’s estate near Nizhny Novgorod, recovering from a severe wound he suffered in March 1611 during the battle for Moscow.

In early April 1612, the troops arrived in Yaroslavl. This is where the provisional government, known as the Council of the Land, took shape. It included members of noble princely families, including the Dolgorukies, Kurakins, Buturlins, and the Sheremetevs. But it was Pozharsky and Minin who stood at the helm. At the time, and until Peter the Great, noblemen never signed anything. Therefore, it was Pozharsky who signed on behalf of Minin, appointed by popular election:

All council members signed the issued documents in order of precedence determined by the rank of their respective families.

On September 1-4, they chased Grand Hetman of Lithuania Jan Karol Chodkiewicz away from Moscow, where he arrived carrying supplies for the Poles in the besieged Kremlin. Kuzma Minin demonstrated excellent valour during the battle. Leading a small cavalry, he staged a sudden attack against Chodkiewicz’s vanguard and sowed panic among the enemy troops.

Kitai-Gorod fell on November 1, and the Poles surrendered and left the Moscow Kremlin on November 5. On November 6, the troops were to march into the Kremlin in a solemn procession. When the liberators of Moscow gathered at Lobnoye Mesto, Archimandrite Dionisii of the Trinity-St Sergius Monastery performed a prayer service to mark the militia’s victory.

In December 1612, the provisional government sent letters across the country inviting the most respected people to choose a new ruler. On March 3, 1613, the Assembly of the Land elected Mikhail Romanov to become the Russian Tsar. He accessed to the throne on July 21 of the same year and founded a new dynasty that went on to rule Russia for about 300 years.

In 1613, to mark Moscow’s liberation from foreign invaders, Mikhail Romanov introduced a holiday, which was both an ecclesiastical celebration and a public holiday, to honour the Kazan Mother of God icon, which accompanied the militia during the march to Moscow. Russia marked this day until 1917.

In 1818, just over 200 years after the holiday was created, Emperor Alexander I ordered that a monument to Citizen Minin and Prince Pozharsky by sculptor Ivan Martos be installed on Red Square. On November 4, 2005, its replica by Zurab Tsereteli, a gift from Moscow’s Mayoral Office, was unveiled in Nizhny Novgorod.

In Russia’s recent history, National Unity Day was reinstated in December 2004 and has been marked annually since 2005.

President of Russia Vladimir Putin: